These (SPITFIRES) bore standard RAF camouflage and roundels, plus red-and-white Polish checkerboard insignia. They outperformed the P-40s that he was used to. They weighed less, had more horsepower, flew faster, and maneuvered better. Their two-speed superchargers and radio-equipped oxygen masks enabled the Mk IXs to operate at altitudes up to 30,000 feet (compared to 20,000 feet for the P-40s). They were better than the P-40s in every respect except diving; they were just too light.

At that time fighter combat was not too intense, just fighter sweeps out over the Channel: "rodeos" - fighter-only missions and "circuses" – missions which included a few bombers as lures for the Luftwaffe. The Spitfires' short range prevented deep penetration raids. Tactically, the Poles used a "line abreast" or ' finger four' formation, which allowed everyone to keep an eye on someone else's tail.

He flew his first Spitfire mission in early January 1943. . a circus to LeHavre; he was flying wing for Tadeusz Andersz. They escorted a small formation of twin-engine bombers. It was an uneventful mission. . no contact with the Luftwaffe. Gabby flew several more missions in with the Poles, becoming quite familiar with the corner of France within the Spitfire's range.

He encountered the Germans on February 3, when a group of FW-190s jumped his squadron on a circus to St. Omer. As the dogfight developed quickly, Flt. Lt. Andersz called on Gabby to fire at a German right in front of him. All that the excited young flier could see were two small dots far away. . so he fired at them. When they returned to Northolt and reviewed the gun camera footage, Gabreski was shocked to see an FW-190 in plain sight…….right in the lower corner of the screen. On the other hand, on this first combat mission, he learned that he had to keep calm. He also observed the Poles' strict radio discipline. And he saw how difficult it was to estimate the range to target.

He flew another 25 missions with the 315th, but had no more encounters with the Luftwaffe. In February 27, 1943, he rejoined the U.S. Eighth Air Force, assigned to Hub Zemke's 56th Fighter Group, flying P-47 Thunderbolts.

Two things struck him:

- 1. the immensity of the P-47 with its 40 foot wingspan and

2. the military bearing of the 56th personnel under the influence of Hub Zemke.

Gabreski was assigned to the 61st Squadron, commanded by Major Loren G. "Mac" McCollom. Its pilots had all been through training together, and regarded Gabreski, as a bit of an outsider. Merle Eby introduced him to the P-47 and showed him its operation, especially the turbocharger that required careful monitoring.

Despite its size, the P-47 was a nice handling plane, with the smooth roar of its big radial engine. Its climb performance wasn't much; but it had outstanding roll and spectacular dive speed. Gabby liked its efficient cockpit heating system and its eight .50 caliber machine guns.

The 56th trained during March and adopted the "finger four" tactical formation. In keeping with his rank of Captain, Gabby was made a flight commander. In April 1943, they flew their first combat missions. They saw more combat in May; some pilots scoring, a few others being shot down. But action continued to elude Gabby. He was finally able to claim a damaged FW-190 on May 15, 1943, but didn't encounter any more opposition for the next month. In early June, the reserved Hub Zemke called Gabby into his office, explained that Squadron Commander "Mac" McCollom was being moved up to Group Exec, and offered him the command of the 61st Fighter Squadron with the rank of Major.

Forty years later Gabby could still recall his shock at this unexpected honor. He wrote in his autobiography, ‘Gabby: A Fighter Pilot's Life’ .that he stammered his acceptance "with as much military bearing as I could muster. A year earlier I had been a carefree Lieutenant on the beaches of Hawaii, learning how to fly…….now I was CO of a P-47 squadron, about to lead it into combat against the toughest opponents on Earth."

He led his squadron with skill and courage……but victories eluded him. His frustration ended on August 24, 1943, when he scored his first victory. From that day on, victories came frequently, often by doubles and triples, until he led AAF fighter pilots in the theater.

In the book American Aces Great Fighter Missions of WWII, Gabby described a mission on December. 11, 1943 as the most exciting of his tour in Europe. The weather was perfectly clear as he led the 61st Squadron on a bomber escort mission. Minutes after take-off, they were over the icy waters of the North Sea. His sixteen P-47s of the 61st were a part of a 200-strong fighter escort that 8th Fighter Command had ordered for the raid. They continued the long climb to altitude, reached 11,000 feet and continued to climb towards their goal of 22,000 feet.

As they reached the northern coast of Holland, they approached 20,000 feet, cruising at 250 mph, looking to rendezvous with the bombers. When they came up to the bombers, Gabreski and his fighters saw the bombers under attack by German 109s and 110s. The twin engine 110s were equipped with rockets to fling at the bombers. As his squadron turned to go after the 110s, two of the fighters collided and exploded.

The German attackers scattered in every direction. The sky erupted into a wild melee of American bombers trying to hold formation, others going down in flames, U.S. fighters hurling themselves at the German attackers, German fighters swirling around, and German fighter-destroyers firing rockets.

Gabreski focused on a trio of Bf-110s that broke down and away. As usual, the superior diving of the P-47 allowed him to catch them, and shoot down the "tail end Charlie." His comrades took care of the two other Bf-110s. He watched his victim plunge down, then searched the sky fruitlessly; he couldn't see any other planes from the 61st. And worse, he was now getting low on fuel.

He briefly tried to join up with a group of radial engine fighters, but he edged away when he realized they were FW-190s. When he checked his fuel again, he realized that he might not have enough to get home. He headed west, and leaned out the mixture a little more than was safe, adjusted to the most economical cruising speed and altitude, and prayed.

As Gabreski was checking gauges, he spotted a lone plane coming in at 3 o'clock. It turned out to be a Bf-109. With his fuel situation, Gabby was in no position to dogfight the German, nor to take evasive action that would take him further from England.

As the German made firing passes at him, twice Gabby sharply flew into his assailant, but continued his westward course. On the third pass, the German's shells hit, shot away a rudder pedal and part of Gabreski's boot. Even worse the engine had taken hits and began to run rough. The Thunderbolt started to spiral down, and Gabby let it go as long as he dared, playing 'possum' for the FW-190 pilot. The ruse worked for a few seconds, but the German quickly dived in pursuit. Gabreski reached the low clouds in time and eluded his pursuer. Nursing his damaged fighter and low on fuel, he reached the advanced strip at Manston.

D-Day and Shot Down

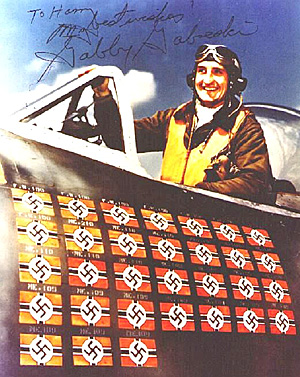

On June 6, 1944 - D-Day, Gabreski led his squadron in long fighter sweeps over the beaches of Normandy. Three weeks later, he surpassed Rickenbacker's World War I record and on July 5th scored his 28th victory making him America's leading ace. When Gabreski's total reached 28 air victories and 193 missions, he earned a leave back to the States. While waiting to board the plane that would fly him to the US, Gabreski discovered that a mission was scheduled for that morning. He took his bags off the transport and wangled permission to "fly just one more."

After his plane was armed for battle, he met no opposition over the target. Seeking targets of opportunity, he spotted enemy fighters parked on an airdrome. During his second strafing pass, his plane suddenly began to vibrate violently and crash landed. Uninjured, he jumped to the ground and ran toward a deep woods with German soldiers in pursuit. Eluding them for five days, he began to make his way toward Allied lines. He encountered a Polish-speaking forced laborer whom he persuaded to bring him food and water. But eventually he was captured and interrogated by the famed Hanns Scharff.

Finally transferred to Stalag Luft I, a permanent prisoner of war camp holding Allied air officers, he was barracked in one of the 20-man shacks surrounded by two rows of barbed wire fence.

There he shared the bad food, hunger and punishments, if possible. But he was proud of the men's spirits under such miserable circumstances, for they had their own clandestine radios to listen to war news, a newspaper printed under the very noses of their guards, and supervision of the simultaneous digging of as many as 100 escape tunnels, few of which led to freedom.

By March 1945, after Gabreski was given command of a newly completed prisoner compound, food was at rock bottom. But he did not lose faith. Soon he began to hear artillery to the East. When Russian soldiers arrived, it was a joyous occasion and soon American planes evacuated the airmen to freedom.

After the war, Gabreski spent several years in flight testing and in command of fighter units before he succeeded in getting an assignment to Korea. In July 1951, now-Colonel Gabreski downed his first MiG, flying an F-86 Sabre jet, despite its unfamiliar new gunsight which he replaced with a piece of chewing gum stuck on the windscreen. Two months later, after a huge dogfight over the Yalu on Sept. 9, he was pleased to congratulate two of his pilots, Capt. Richard Becker and 1st. Lt. Ralph Gibson, when they became the 2nd & 3rd American jet aces.

In December 1951, he transferred to the 51st FIW. In April 1952, he scored his fifth kill of the Korean air war, to become one of the few pilots who became aces in two wars. That summer, cooperating quietly with Bud Mahurin, Bill Whisner, and other commanders, he participated in the clandestine 'Maple Special' missions across the Yalu River, into Manchuria. He was credited with 6.5 kills in Korea.

He ended a distinguished Air Force career as commander of several tactical and air defense wings. After his retirement from the Air Force, he worked in the aviation industry and as President of the Long Island Rail Road. He lived in retirement on Long Island, for many years as "America's Greatest Living Ace". He passed away on Jan. 31, 2002.

Back to KTB # 177 Table of Contents

Back to KTB List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Harry Cooper, Sharkhunters International, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Join Sharkhunters International, Inc.: PO Box 1539, Hernando, FL 34442, ph: 352-637-2917, fax: 352-637-6289, www.sharkhunters.com