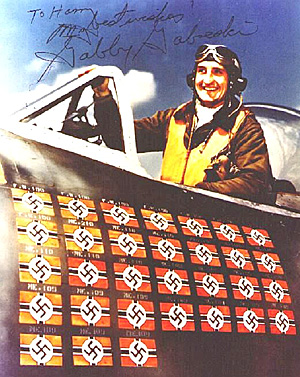

While we realize that this piece is not about submariners, U-Boats or the like, but FRANCIS “GABBY” GABRESKI (EH112-+-1994) was a Charter Member of our former sister-organization EAGLEHUNTERS until his death and was a great fighter pilot so we thought this would be an article you would enjoy.

" This is your last chance, so give it your best," the flight instructor said to Aviation Cadet Francis S. Gabreski. Gabby took the plane up and put it through the basic required maneuvers, stiffly, but competently enough to convince Captain Ray Wassel that he might make a decent pilot. After an indifferent two years at Notre Dame, Gabreski had enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1940, and had had a tough time of primary flight training.

Trainee Gabreski was a shaky pilot who didn't get on well with his first instructor, Mr. Myers. He was scared to death during his first solo, and afterwards knew that he wasn't progressing as fast as the other students. Mr. Myers' brusque and demanding style just didn't match up with Gabreski's uneasiness and awkward handling.

Eventually, Mr. Myers scheduled an "Elimination Flight" for him with an Army flier, Captain Ray Wassel. An "Elimination Flight" was just that, a cadet's final chance to prove himself worthy in the opinion of an Army officer. Thus in September 1940, Captain Wassel told Gabby Gabreski, America's future 'Greatest Living Ace', to step into the plane and give it his best.

…..He was a marginal pilot…..

He flew well enough for Capt. Wassel to draw the same conclusion as he himself had drawn. He was a marginal pilot, but probably could do better with a new instructor. He was assigned to a different instructor and in November 1940 completed primary flight training without further problems.

Young Francis Gabreski was relieved not to let down his parents. Both of them had emigrated from Poland in the early 1900's. He grew up in tough family circumstances as his Dad got sick and couldn't keep his physically strenuous job with the railroad. To support the family of five children, his Dad borrowed enough money to buy a grocery store, and worked at it twelve hours a day. Like many immigrant-owned small businesses, all the family members worked at the market. Francis was an average student and did not dream of aviation like many boys of the era did.

He graduated from high school in 1938, and as his parents were determined that their children would go to college, Gabby went to Notre Dame. Unprepared for real, academic work, he almost flunked out in his freshman year. But at college, he developed his first interest in flying, thinking that it would be a neat way to get back and forth between Oil City and South Bend; never mind that Oil City didn't have an airport.

Better than a ‘marginal’ pilot

He took flying lessons from Homer Stockert, owner of Stockert Flying Services, in a Taylorcraft monoplane, but after six hours under Mr. Stockert's patient tutelage, he just couldn't get the hang of flying. He continued at Notre Dame, starting his second year there as war raged in Europe and Poland was invaded. When Army Air Corps recruiters visited the campus, Gabby went to hear them, largely because some friends went too. The Army's enticing offer impressed him, especially the program's waiving of an academic test, and he enrolled, reporting in July 1940 to Pittsburgh for a physical and induction into the Army.

He went to primary flight training at Parks Air College, a civilian program that the Army used for its novice cadets. Here they flew Stearman biplanes and Fairchild PT-19 low-wing monoplane. Gabreski struggled through primary training, barely avoiding being washed out in the elimination flight described above. But he passed, got a new instructor, and in November 1940, he completed Primary flight training.

He reported to Gunther Army Air Base outside of Montgomery, Alabama, for basic flight training. Unlike Parks College, this was real Army; everyone was in khaki, lots of saluting, the whole bit. Here he flew the Vultee BT-13, a more powerful and less forgiving plane, and so noisy that the cadets called it the Vultee Vibrator. On this plane they learned instrument flying with a hood over the student's cockpit, which enabled them to begin learning how to fly in bad weather.

…..the first fatality…..

Here Gabby saw his first fatality, when a student pilot named Blackie went into a spin and bailed out, but the propeller chopped his legs off and he bled to death before he reached the ground.

After completing basic training, Gabby moved over to nearby Maxwell Field for Advanced training. Here they took a big step up and started flying the AT-6. It was almost like flying a fighter. But at Maxwell, Gabby almost washed out again, this time for fainting at early morning parade when he was badly hung over. He compounded the problem by not immediately explaining his reason for passing out. From the Army's point of view, a pilot who fainted for no apparent reason was an unacceptable risk, while one who fainted because he was hung over was merely a mild disciplinary issue. But before it got to expulsion, Gabreski coughed up the actual reason and apart from some extra guard duty and other punishments, escaped further repercussions.

He graduated in March 1941 and was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. and he received his first choice of duty assignments - fighter planes in Hawaii. He traveled there in the SS Washington, passing through the Panama Canal and San Francisco en route. About 20 Second Lieutenants were in his group assigned to Wheeler Field on Oahu. It was a beautiful green, sod field (sod being easier to maintain and easier on airplane tires than concrete), with rows of Curtiss P-40s and P-36s.

Two Fighter Groups with about 75 planes each used Wheeler Field. Gabreski was assigned to the 45th Fighter Squadron. They flew only powerful (1000+ hp), single-seat fighters. The P-40 had a lot of torque and in Gabby's first flight in one, he narrowly avoided crashing on take-off and landed bumpily but safely.

The pilots flew about 30 hours a month, usually at 5,000 to 10,000 feet, never higher because they didn't have oxygen equipment. Flying was hard work, following all the leader's twists and turns, working the manual controls, and pulling heavy G's.

After a day's flying, they hung out at the Officers' Club, mostly talking about flying, reviewing each other's performance, and trying to improve their skills. In Hawaii, Gabby met Kay Cochrane, niece of an Army colonel. They began dating in late 1941, and had their first falling out on the night of December 6, 1941. That night young Lt. Gabreski went to bed quite concerned about his future.

As he awoke on the morning of the 7th, shaving and worrying about his girlfriend, he heard some explosions, which were fairly common at a military base. Then he saw a gray monoplane with red circles and fixed landing gear flying overhead. He realized the Japanese were attacking. He heard louder and closer explosions and saw smoke from the burning airplanes. The aircrews hustled over to the airstrip and pulled out some undamaged planes. Captain Tyler, the squadron CO, ordered them fueled and armed. About 10 planes were readied, and Gabreski was one of the pilots selected to fly.

As they flew over Pearl Harbor, they could see that everything was a horrible, burning mess. Jittery AA crews fired away at anything in the sky, including the P-36s and P-40s. Gabby and his group searched the area for about 45 minutes, but the Japanese planes were long gone.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Gabreski realized that everything about his life had changed. They flew constant daytime patrols, which quickly wore out both men and machines. They received new planes, P-40E's and Bell P-39 Aircobra, both of which had their drawbacks. The Model E Warhawk was even heavier and more sluggish than its predecessors, and the Aircobras had an unfortunate tendency to tumble.

Throughout the summer of 1942, the squadron pilots led a fairly dull life: gunnery practice and flying patrols. With the Pacific shaping up as primarily a Navy theater and his strong feelings about the German invasion of Poland, Gabby wanted to get into the European Theater. Capitalizing on his ability to speak Polish, he got the idea to transfer to one of the RAF's Polish squadrons. The War Department okayed the idea. In September 1942, after a brief visit with Kay and his family in Oil City, he was promoted to Captain and shipped out to England.

In October of 1942, the new Captain Gabreski reported to Eighth Air Force Headquarters in England, to finalize his assignment to the RAF Polish squadrons. 8AF HQ seemed to him to consist of about 20 people running around in complete confusion, none of whom knew about him or his pending assignment. After some weeks of inaction, he met some Poles from the RAF in London's Embassy Club. He introduced himself to them in Polish and explained his proposal to them. They were very enthused, and were interested generally in America's war plans. His new friends promised to help him. And, eventually, the Commands issued their approvals.

He reported to Group Captain Mumler at Northolt in December 1942. Northolt held six Polish squadrons of Spitfires; it boasted a macadam runway and permanent buildings. Captain Gabreski was assigned to 315 Squadron, which was receiving the new Spitfire Mark IX fighters.

Back to KTB # 176 Table of Contents

Back to KTB List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Harry Cooper, Sharkhunters International, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Join Sharkhunters International, Inc.: PO Box 1539, Hernando, FL 34442, ph: 352-637-2917, fax: 352-637-6289, www.sharkhunters.com