In the years between the Sikh Wars and

the First World War the British in India launched

over forty expeditions against the tribesmen of

the Northwest frontier. As the British presence

on the frontier increased and their policies

changed so did the nature of frontier expeditions.

In the years between the Sikh Wars and

the First World War the British in India launched

over forty expeditions against the tribesmen of

the Northwest frontier. As the British presence

on the frontier increased and their policies

changed so did the nature of frontier expeditions.

By the 1890s due largely to the rapidly expanding railway system, British Field Forces were of divisional and even corps size, fielding tens of thousands of troops in operations designed to inflict massive and impressive punishment on rebellious tribesmen. For added effect these large scale expeditions were often advertised ahead of time complete with intended objectives so as to cow the enemy in advance.

The expeditions of earlier years were of a different nature. Before the advent of railroads on the frontier, troop concentrations were difficult to assemble and maintain. Available forces tended to be dispersed in smaller bodies and to concentrate in one sector meant stripping another. Within these limitations keeping peace on the border evolved into a raid and counter raid form of warfare.

Local commanders dealt with cattle raids, armed outrages and border ruffianism with their own limited resources: launching short, sharp and limited punitive raids. Typically these expeditions consisted of battalion or smaller sized task forces. These small scale excursions usually had limited objectives such as collecting unpaid fines, arresting perpetrators, or punishing a local outrage.

Successful small scale punitive expeditions generally observed three principles: secrecy, speed, and economy of force. These tended to be interrelated. In an area where news proverbially "flew on the wings of the wind" secrecy was the most essential and difficult to maintain.

Secrecy in such operations was necessary to gain surprise and allow a small force to be successful against (or avoid) the potentially large and overwhelming numbers that the natives were capable of assembling. Indeed a small force was easier to keep secret but in turn required more of it and depended on it for success.

Speed or rapidity meant rapid movement and being able to reach the objective quickly. This was necessary to maintain surprise and secrecy once the expedition was underway. Speed was also essential after the raid to ensure a quick getaway before the natives had time to react.

Economy of force was usually dictated by circumstances and meant using just enough force to achieve the objective. This was important on the frontier especially in the early days, when resources were scarce. Economy of force was also a prerequisite to the above principles.

Large forces unlike smaller (and usually

more economical) forces could not easily be

kept secret, did not move very fast and were not

readily available anyway. These three principles

could easily be summed up as "getting there

fastest with the mostest" (sic).

[1]

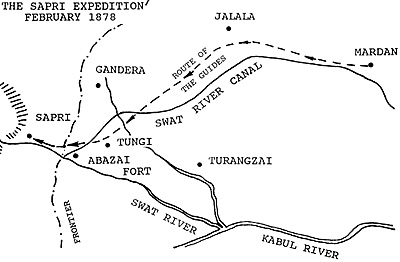

The 1878 raid on Sapri while an

insignificant event in the annals of NWF military

operations provides an excellent example of a

small scale punitive operation and illustrates the

principles of secrecy, speed, and economy of

force. This raid had its

origins back in December of 1876.

At that time the British had just started

construction of the Swat River Canal. The canal

tapped the River at the point where it crossed

the border near the frontier fort at Abazai,

opposite Utman Khel territory. The local Utman

Khel

[2]

viewed the project with suspicion and

annoyance as it interfered with some of their

cultivated land.

In the early hours of December 9th a

group of about 100 tribesmen surrounded a

work camp of some 65 unarmed coolies.

Around two o'clock in the morning at a given

signal the Pathans rushed the camp and cut the

tent ropes. The defenseless workers were cut

down through the tent cloths or as they tried to

emerge. The camp was plundered and the

raiders escaped back into the hills before troops

could arrive from the nearby Abazai fort. Six

workmen were killed and twenty-seven

wounded.

The British were taken aback by the

attack. They realized that proper precautions or

a proper escort would have deterred an attack

but they never expected an unprovoked attack

on unarmed Moslem workmen. The government

was able to implicate Mian Rakan-ud-din, the

Khan of Sapri as the instigator of the attack.

Sapri was a village lying just across the border

some seven miles from the Abazai fort and

some forty miles northwest of Mardan, the

cantonment of the Corps of Guides.

[3]

The local political officer, captain P.L.N.

Cavagnari, deputy Commissioner of Peshawar,

[4] levied a

fine of money and cattle on Mian Khan and

ordered the actual murderers turned over to

British justice. Mian Khan ignored the demands

and Cavagnari as was his policy planned a

punitive strike. The exigencies of the looming

Afghan crisis interfered and operations were

postponed until 1878.

At the beginning of that year the

government sanctioned a punitive raid on Sapri

to be made by the Guides. To ensure absolute

secrecy Cavagnari told no one but captain

Wigwam Battye of the Guides of his plan.

Captain Battye would command the force while

Cavagnari would accompany as political officer.

Cavagnari plannedarapid night march and a

dawn surprise attack on the village by some 270

Guides followed by a rapid withdrawal via the

Abazai outpost.

Economy of force was determined by the

troops available for the strike, no more could be

spared for the operation. The force would

include 4 British and 10 Native officers; 255

Guides cavalrymen, and 11 Guides Infantry

mounted on mules for rapid movement.

The departure was set for seven o'clock

on the evening of February 14th. So secret were

the preparations that the officers were playing a

game of racquets when ordered to prepare to

start. At evening roll call the fort gates were

shut to prevent anyone from leaving and extra

ammunition was issued to the troops. A cheer went up from old

veterans who knew this meant a raid.

The 255 "sabres", 11 "bayonets", and their

officers set out on their long night march. The

infantry regulated the pace but being mounted

on picked animals were able to keep up. The

planned route would take them along the main

road to Tungi and Abazai but the column was

careful to detour well clear of native villages.

The column skirted around Jalala and on

approaching Tungi near the border left the road.

The force detoured northward and crossed the

Swat Canal into the hills.

As the terrain was now unsuitable the

column halted and dismounted about 2 miles

from Abazai. Here the horses were left with 63

men who had orders to take the mounts at

daybreak to the Abazai fort and await the return

of the column. In some seven hours the Guides

had covered 32 miles and had yet to cover the

remaining 8 miles on foot before dawn.

The dismounted force now proceeded

through some rough plowed land and then along

the north bank of the Swat River for some 4

miles to where a mountain stream entered the

river. They then followed the stream up along a

steep mountain path to a Kotal overlooking the

village of Sapri. It was four o'clock in the

morning and the village was now within easy

rifle range.

An attempt to reconnoiter the village was

abandoned when some of the village dogs began

barking and it was decided to hold back, deploy

and wait until daybreak. Cavagnari's intelligence

indicated that Mian Khan would most likely be

found in the village mosque or in his own tower

both near the center of the village. In the

meantime Captain Battye deployed a piquet on

the spur overlooking the village center.

At daybreak the Guides rushed the village,

achieved complete surprise and easily seized the

mosque. Even as the villagers awoke the

soldiers were standing over

them with sword and bayonet though in the

confusion many warriors were able to escape

into the hills. Securing the mosque but not

finding Mian Khan, the soldiers proceeded to the tower.

The Khan had hidden in a building behind

the mosque which the Guides soon surrounded.

The British demanded his surrender and

threatened to burn him out. Mian Khan stepped

out to surrender but as he was being arrested he

drew a dagger and the Guides shot him dead.

The other defenders of the house quickly gave

up. At this time the only flaw in the operation

became apparent. Cavagnari had intended to

blow up the village tower but the explosives had

not come up in time. Cavagnari decided not to

burn the village.

In the meantime the villagers who had

escaped began sniping at the troops in the village

from the surrounding heights. They had

occupied a hill to the southwest overlooking the

Guides' retreat route. It was time to withdraw.

Captain Battye and a detachment rushed the

position and drove off the Pathans.

The withdrawal was conducted in good

order without huffy or harassment. by 11:00 am

on the 15th the troops had reached Fort Abazai.

They had defeated some 300 enemy in the raid,

killed seven of them and captured six. Casualties

among the Guides were eight wounded.

After this successful raid the government

called ajirga of the Utman Khel to spell out the

terms of their punishment for the Abazai

outrage. These included a general fine and blood

money for each coolie killed or wounded,

restitution or compensation for plundered

property, and hostages to be turned over as a

guarantee for one year's good conduct by the

tribe. These were considered lenient terms for

an offense of such gravity. All but a couple of

the Utman Khel villages agreed to the terms and

the British left well enough alone.

The raid on Sapri like many other small

expeditions proved successful and an example

of good planning and execution. However the

results of such small expeditions proved only

temporary and did not bring about more settled

conditions on the frontier. The tribesmen were

used to losing as much or more in tribal disputes

of their own and came to accept such losses as

the cost of doing business. The result would be

larger and more destructive British invasions in

the future.

Intelligence Branch, Army Headquarters

India, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions

from India Vol. I pt. 1 Tribes North of the

Kabul River, Delhi: Mittal Publications, (1983

reprint)

Nevill, H.L., Campaigns on the Northwest

Frontier, Delhi: Neeraj Publishing House

(1984 reprint of 1912 ed.)

Younghusband G.J. Indian Frontier

Warfare, London: Kegan Paul, Trench,

Tubner & Co. Ltd. 1898

Operations on this scale were not to last

much longer than twenty four hours as supplies

were an issue and in any case stockpiling of any

large amounts would preclude secrecy and

speed. In some cases supplies could be sent to

meet a returning party or a returning party could

detour to a prearranged cache.

Operations on this scale were not to last

much longer than twenty four hours as supplies

were an issue and in any case stockpiling of any

large amounts would preclude secrecy and

speed. In some cases supplies could be sent to

meet a returning party or a returning party could

detour to a prearranged cache.

NOTES

[1] Attributed to American Confederate

General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

[2]

The Utman Khel were a prominent

Northwest Frontier tribe occupying the hill

region north of Peshawar on both banks of the

Swat River. They numbered about 40,000

people including some 9,300 fighting men.

[3]

The Corps of Guides was perhaps the

preeminent unit of the Punjab Frontier Force.

Raised in 1846 the Corps consisted of both

infantry and cavalry components and was

based at Mardan.

[4]

Pierre Louis Napoleon Cavagnari (1841-79)

was a prominent political officer on the

frontier. He would later head the British

mission to Kabul at the end of the first phase

of the Second Afghan War. He and his escort

of Guides were killed in a heroic last stand at

the residency against rebellious Afghan

troops.

SOURCES

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XXIII No. 3

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com