The months following the Battle of Chuenpi were relatively quiet. Charles Elliot had accepted the Chinese challenge on his own initiative, now he had to find out if his action was approved in London. After all, he did not expect to take an the Chinese Empire with a few warships; therefore, all he could do was wait for further instructions from England.

Meanwhile, Lin decided to write a long letter to Queen Victoria on the immorality of opium trade; including a declaration that all relations between China and Britain would be severed. Britain was forbidden to trade with China as a punishment for her hostile acts. Other foreigners, however, were not implicated is long as they continued their observance of Chinese law.

Elliot's dispatch on "The Siege of the

Factories" and the news of the forced surrender

of the opium had reached England. There was a

fierce debate on whether Britain should declare

war on China. [1]

The peace faction argued that the British

government should not disgrace herself by

supporting a trade of shameful contraband,

whereas the war faction contended that Britain

should protect her subjects and her trading

rights (carefully avoiding any mention of

opium).

In February 1840, Lord Palmerston,

Secretary of Foreign Affairs, sent in ultimatum

to the Chinese governsent, demanding reparation

for surrendered goods and the imprisonment of

British merchants, and security for the right of

future British trade. A state of war would exist

until all of Britain's demands were satisfied.

The expeditionary force was to be

organized by the Governor-General of India, Lord

Auckland. He began by summoning the 18th

Regiment (The Royal Irish) from Ceylon and the

28th Regiment (The Cameronians) from Fort

William in Calcutta. They were joined by the

49th Regiment (Hertfordshires) a Bengali

volunteer unit [2] , two Madras Artillery

companies and two companies of sappers and

miners. The land force totalled about 4,000 men.

[3]

The naval vessels numbered about 20,

including three ships-of-the-line, two frigates

and several other warships and armed steamers.

When pitted against an empire of enormous

manpower, such a small expedition was to be used

as an army of demonstration. Its primary goal

was to awe the Chinese with its force of arms.

The expeditionary force was to assemble at

the end of April at Singapore, the base of

operations for the British fleet in the Far East.

One forerunner of the expedition, the 44-gun

frigate DRUID, was the first ship to arrive in

Hong Kong. [4]

Its appearance assured the British civilians that they were not forgotten by their

government.

Placed in command of the naval squadron

was the Honourable Sir George Elliot, a cousin

of the Superintendent in China. The two Elliots

were to be joint plenipotentiaries of the

expedition.

Palmerston's instructions to Admiral

Elliot were to blockade Canton, occupy Chusin (an

archipelago at the south of the Yangtze), deliver

a letter to the Minister of China, and to sign an

agreement off the south of the Peiho [5] with a

representative of the Imperial Government. The

use of force was to demonstrate, not to conquer.

The blockade of Canton was quickly

established. This gesture did not leave such

impression on the Imperial Government since the

officials in the capital could care less about

maritime activities in the South China Sea.

The next task was to deliver Palmerston's

letter to the Imperial government. It was not

delivered in Canton as planned, instead the two

plenipotentiaries decided to hand the letter over

to Chinese officials on the Island of Amoy, which

lies about halfway between Canton and Chusan. The

letter was to be delivered by the 42-gun frigate

BLONDE, commanded by Capt. Bourchier. A Mr. Thom,

a British merchant [6] who understood Chinese, was ordered

to approach the Chinese position on board the

frigate's cutter, and to deliver the letter to

the ranking Imperial official. Them carefully

sent out a note explaining the nature of the

white flag and the purpose of his visit.

Apparently the note had no effect, for when he

approached the shore, an angry mob gathered,

making menacing gestures. Theo returned without

landing.

Next morning Thom tried again and this

time the mob reacted even more violently. As

soon as the envoy got within range, the Chinese

fired a fusilade of arrows and cannon shots. The

cutter started to withdraw in haste when the

BLONDE let loose a broadside of 32-pound shots,

killing half a dozen Chinese and putting the

remainder to flight.

After Them regained the BLONDE, Capt.

Bourchier decided to send a message protesting

the violence shown the envoy. He slipped the

message in a battle, dropped it over the side,

and saw a fisherman pick it up. He then set fire

to a junk lying nearby and resumed his voyage

with the rest of the fleet towards Chusan.

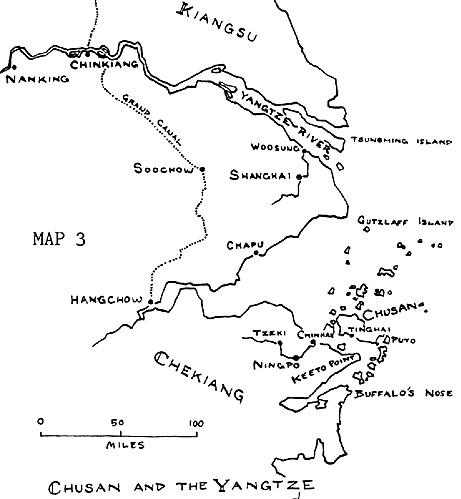

The fleet was to rendezvous off Buffalo's

Nose (see sap 3), about 30 miles south of

Chusan. The whole fleet gathered an July 1st and

advanced an Chusan the very next day. Its

destination was the port of Tinghai, largest

city on the island of Chusan.

In Tinghai's harbor there stood a dozen

war junks carrying pennants indicating in

officer of considerable rank. Commander Brener

decided to row over and negotiate. Thee's

experience was not repeated, Bremer met with the

commander of the Tinghai garrison, Chang Choa-Fa, and demanded the surrender of the Chinese

forces. The Chinese commander rejected the

English proposition and seemed determined to fight.

The next morning the British expected to

take Tinghai by force for the Chinese were seen

strengthening their defenses. All the English

warships took up line about 200 yards from the

sea Nall, part broadsides bearing. An invasion

force waited behind in longboats, consisting of

part of the Caseronians, the grenadiers from the

Royal Irish, the Royal Marines and the Madras

Artillerymen with two 9-pdrs. They were opposed

by Chinese war junks gathered right along the sea wall.

By two o'clock, the Chinese showed no

sign of surrender. At 20 minutes past the hour,

Bremer ordered a single round to be fired an a

guard tower. The shot was answered by the

Chinese flagship. At once Bremer gave the signal

to engage. For 10 minutes the whole British

fleet fired away as the amphibious landing force

raced toward their objective. British ships had

been hit several times and one sailor was

wounded. The Chinese had four war junks shot to

pieces and the rest badly damaged. By the time

the landing team reached the sea wall, the

defenders had fled, leaving their dead and

wounded. Commander Chang suffered a broken hip

and was carried away. The assault force landed

without further incidents.

The grenadiers of the Royal Irish took

Joss-House [7] Hill, which dominated the

surrounding fields. A party of the Cameronians

and a detachment of the Madras Artillery were

entrusted with the task of taking Tinghai, less

than a mile assay. They moved with difficulty

along a single raised path, but their night

advance was uneventful except for some cases of

food poisoning and a minor fire in their camp.

At first light the next morning the

British on Joss House Hill saw streams of

Chinese refugees hurrying out of the north gate

of the city and guessed correctly that Tinghai

had been left undefended. Several young officers

ventured toward the south gate, drew no fire,

and decided to go for it. They crossed the moat,

climbed over the 20-foot high wall on a ladder,

cleared the entrance of grain sacks and let in

their compatriots. Tinghai became the first

British possession in China.

Most of the inhabitants left the city

with the exception of the magistrate, who

committed suicide. At that time the British

found the Chinese practice of suicide rather

than surrender surprising, but they soon learned

in the next few months that suicide was a common

Chinese reaction to the occupation of a town by

foreigners.

While the town was occupied without

difficulty, the establishment of a base proved

to be the gravest blunder made during the whole

campaign. The campsite was chosen without

consulting the regimental surgeons. The tents

were being pitched in low-lying paddy fields,

often surrounded by stagnant water. It was not a

healthy environment in the great heat of the

Chinese summer. A further error was made by

allowing the Chinese to leave town and take

their belongings with them. As a result, Tinghai

was left an empty city which deprived the British

of such-needed supplies and labor. The price for

these blunders was to be paid in the coming months.

The Opium War Part 1

Introduction

The Opening Shot

The First Expedition

On to the Peiho

Battle of the Bogue

The Ransom of Canton

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XIX No. 3

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com