In part one I described the origins of the Men of the North (Gwyr-y-Gogladd); Where they operated and what their clothing and equipment were like. In this issue we will be looking at the Internectine Warfare among

the Princes in the North and different aspects of warfare they carried

out. Finally a look at some rules and 15mm figures that are available for this period.

In part one I described the origins of the Men of the North (Gwyr-y-Gogladd); Where they operated and what their clothing and equipment were like. In this issue we will be looking at the Internectine Warfare among

the Princes in the North and different aspects of warfare they carried

out. Finally a look at some rules and 15mm figures that are available for this period.

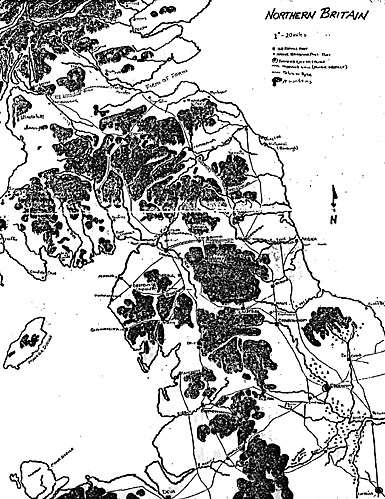

Jumbo Map of North (extremely slow: 655K)

The Men of the North fought among themselves throughout most of their short history. Occasionally a strong leader could pull them together for a single venture against common threat. This was a heroic society as old tribal areas of the Celts consolidated into kingdoms, members of dynasties (real or imagined) struggled among each other for reputation, and wealth, and the power that go with it.

The basic form of power was military - i.e. the warband. There is little evidence which can verify how much of the Roman tradition of a standing army carried over to the mid - 5th and early 6th century. Certainly, the Roman Frontier army at the wall was little more than a farmer-militia by 450 AD. By 500 AD even this militia was probably a memory, the leaders relying on warbands of professional warriors

Supported by levies in case of invasion or raids by their neighbors. A line in the Gododdin suggests that the warbands were divided into troops of 30 men. It is unclear what percentage of the warband fought mounted or if any fought on foot. I suspect that at the core of each warband there was a group of man who could fight equally well an foot or mounted as cavalry. Possibly, the whole army rode to battle them dismounted to fight. There is evidence for both, the men from Gododdin fought mounted when they attacked Catraoth, while Urien's host throw up ramparts on a high hill -- apparently to fight on foot. There is also references to raiding from the sea in which case a warband or part of one would act like marines. It would seem that the warband was a very versatile fighting force and that the distinction as cavalry or infantry would depend on the number of horses available to them.

Why Fight

There are four major reasons why the men of the North fought among themselves. First was to gain prestige and a reputation as a great leader.. A prince who had a good reputation could draw good fighting men from all over the island to their warband. The stronger the warband the more respect his peers would give him and the more power he would hold.

Secondly, in order to got the reputation as a leader and to attract a larger following a Prince would have to use his warband. This would also keep his men in fighting shape.

Third, cattle and slave raids brought additional income to the prince. Wealth was measured by the amount of cattle one owned and the slave trade was a very lucrative sauce of income. The silver hoard from the continent found buried at Traprain Law suggests that piracy was not above some of the inhabitants of this region. They would use this acquired wealth to spread among their followers and to buy luxury items from the continent. Kings and nobles are always in need of wealth. Geoffrey of Monmouth described Arthur as courageous and generous and once he had been invested with the royal ensign, he observed the normal custom of giving gifts freely to everyone. Such a great crowd of soldiers flocked to him that he came to an and of what he had to distribute." (Geoffrey of Monmouth)

The promise of wealth and glory attracted fighting men. Finally, the men of the north fought to settle dynastic and policy disputes. A generation after Dyfnwal's kingdom at Alclute expanded to encompass the region of the Votodini, two Votodini nobles are recorded as defeating their overlord and driving his family from Dumbarton, their Capitol. Dyfnwal may have grabbed the territory to increase the size at his kingdom or to preserve stability after some destabalizing events, but it is apparent that the young nobles did not feel that it should be a permanant arrangement, so around 540 AD Caton at Traprain Law and Morcant Bulc (Morgan the Black) at Yeavering Bell overthrow their overlord. In the 560's Riderick had recovered his family's kingdom with the help of Mordat the uncle at Caton and Nud from Dumfries and Clytno at Edinburg.

Around 590 Urien at Rheged was assassinated by one Morcant, according to legend because Morcant was envious of Urien's fame, but probably more likely because Urien was giving some at Morcant's land, that had been recaptured from the Anglo-Saxons, to his Irish mercenaries as pay. (Morris, 1975)

The most common form of military activity of the men at the north was the raid. There was a tradition that every year the King or Prince would take his warband either to battle or on a raid for cattle, slaves, or booty. The raiding party would probably consist of just the king's cambrogis or companions (the core of his warband). It seems likely that they would have scouted the neighboring kingdom that was to be the target at the raid.

Once the information was gathered, they would seek out the cattle at the neighbor. Possibly camping just out at sight at the herd at cattle and their guards until dawn when they would launch a surprise attack! A dawn attack would allow them 10 to 12 hours at light in which to drive the cattle back to their own territory. It the raiders were sighted coming into the region they might find a warm welcome at a ford or dyke they had to cross on the way out, or possibly need to leave a rear guard to delay the pursuit.

Once back home their exploits would be recounted around the table or hearth. Slave raids would be similar to this except traditional anemias such as the Irish, Picts, or Saxons would be the focus of those. The religion of the target population did not seem to matter much. King Coratic of Alclute raided Christian settlements in Ireland for slaves (which he probably ransomed back to the Irish king or sold to the Picts). (See notes at the end of the article for possible raid wargames.)

Battles were a much larger affairs once the King received word that an enemy host was approaching his torritory (or an ally's) he would call the various districts to arms. Possibly sub-kings, princes, or local chieftains in the district would gather their personal retainers and/ or levy troop% and march to a meeting Place with the king. Scouts would keep track of the location of the enemy warbands and the King would try to move into a blocking Position. Again he maw attempt a dawn attack in which his army would rush in and hopefully surprise the enemy or he might hold a strong defensive position in the path of the invaders.

Sometimes the opposing forces would face each other and shout insults at their opponents. Kings maw give speeches at encouragement to his troops. (A good example of this is the speech King Henry gives his men before the battle at Agincourt in Shakspere's Henry V!) Then the two armies would close and fight until one side broke and routed. There may have been some maneuver before battles there are vague references to planning and organization but in general the poetry left to us focuses on bravery, battlelust, and images at combat from a personal perspective.

Some examples:

- Like waves roaring harsh onto shore

I saw savage men in war-bandss

And after the morning's traw,

torn flesh.

- --Tallson from The Bottle at Gwen

Ystrad

Weapons scattered.

Columns shattered, standing ground.

Great the havocs

The hero turned back the English.

He planted shafts,

In the front ranks, in the spear-clash.

He laid men low,

Made wives widows, before he died.

Hoywgi's son flamed

Before spears forming a rampart.

- --Anorion from the Gododdin

Saturday morning a great battle there was

From the time the sun rose till it set.

Fflamddwyn came on with four war-bands

Goddau and Rheged were marshalled in Dyfwy

fromm Argoed to Arfynydd:

They were not given one day's delay.

- --Talisen from The Battle at Argoed Llwyfain

These are just a few examples at battle tactics, formations, and mobilization as the Poets at the period saw it. Gwen Ystrad was a battle at a ford and the Poet likens the Charge of the (Pict 7) raiders across the river to waves rolling onto a beach. The Goddodin excerpt suggests a shieldwall type formation with spears so dense that they formed a rampart. The excerpt from the Battle of Argood Llwyfain suggests some system of mobilization where by forces from different districts make it to battle. The most obvious advantage of the poems is that they inform us about battles that took place. Which leads us to the following scenario.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Alcocks Losling ARTHUR'S BRITAIN. Now York, Penguin Books, 1977.

Chadwick, Nora K, THE BRITISH HEROIC AGE: THE WELSH AND THE MEN

OF THE NORTH. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1976.

Clancy, Joseph P. THE EARLIEST WELSH POETRY. St. Martins Press.

Goodrich, Norma Larre, KING ARTHUR. Now York: Franklin Watts, 1986.

Morris, John, THE AGE OF ARTHUR. Now Yorks Charles Scribner's and Sons, 1973.

Nicolle, David, ARTHUR AND THE ANGLO-SAXON WARS. London. Osprey Publishing Ltd, 1984.

Thorpe, Lowis (trans) Geoffrey of Monmouth, THE HISTORY OF THE KINGS OF BRITAIN. New Yorks Penguin Books, 1978.

Tolstoy, Nikolail THE QUEST FOR MERLIN. Boston, Little Brown and Company, 1985.

Men of the North Part 2: Internectine Warfare in the British Dark Ages

- Historical Background

Battle of Arthuret

Campaigning with the Men of the North

Wargaming the Men of the North

Jumbo Map of North (extremely slow: 655K)

Back to Saga v5n6 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com