Simon had counted on a large army of reinforcements come Spring. In fact, Philip Augustus, King of France, had mobilized an expedition to assist the Crusaders, but had instead decided to take his army and invade England. Papal authorities also began to preach a new Holy Crusade to the Levant, further eroding any chance for Simon de Montfort's relief (Sumption, pg. 160).

Simon had counted on a large army of reinforcements come Spring. In fact, Philip Augustus, King of France, had mobilized an expedition to assist the Crusaders, but had instead decided to take his army and invade England. Papal authorities also began to preach a new Holy Crusade to the Levant, further eroding any chance for Simon de Montfort's relief (Sumption, pg. 160).

Peter II of Spain now made the decision to militarily retake his former strongholds and further add to his kingdom as well at the expense of the French. Raymond of Toulouse, caught between two enemies, threw his lot in with the Spanish as his kingdom had suffered greatly from the French occupation and his hatred for the depravations of Simon de Montfort far outweighed his hatred of Peter. Raymond, along with the Counts of Foix and Comminges, made a pretext of calling on Spain's aid to assist their continued resistance to a hostile French occupation. Hadn't the Pope himself condemned the Crusaders? Nationalistic sentiments are evident throughout writings from this period as Peter joined the heretics, guided by his political aspirations which failed to consider Simon's small army as any continued detriment whatsoever (Sumption, pg. 114).

In another turnaround, Pope Innocent, upon hearing of Raymond's uprising and the unexpected invasion of southern France by Spanish troops, revoked his order suspending the Crusade, took Raymond's southern lands back under Papal control and forbade Peter II to interfere in the affairs of the Church, admonishing him by writing "We should be obliged to threaten you with Divine wrath, and to take steps such as would result in your suffering grave and irreparable harm", but Peter chose to ignore the threat, feeling that right belonged on the side of the victors, one of whom he felt certain to be (Sumption, pg. 161; Oldenbourg, pg. 163).

Peter had had no problem recruiting soldiers for his army. The Spanish chose to fight for their charismatic king, rather than for their Pope. Over a thousand of the finest Spanish Hidalgos, the experienced and confident knights of Aragon and Catalonia, rode under Peter's banner, looking for wealth and glory. Mobs of militia also joined the glittering array as it crossed over into Toulouse welcomed, as Peter had expected, as liberators from the hated Crusaders. Joining the Spanish army were 600 knights from Toulouse under Raymond and his counts, as well as two hundred other mercenary adventurers, eager to share in the assured victory of Spanish might over the pretentious Simon de Montfort's paltry forces. Peter II twisted honor as an excuse to 'rescue' his sister, apparently trapped in Languedoc at the start of the hostilities, as well as battle to save civilians from the depravations of the 'northern barbarians' (Oldenbourg, pg. 164).

The warriors followed, eager for victory and glory as they had for centuries behind their general. It should not be forgotten that Simon's methods of waging war had virtually assured Raymond's and Peter's popularity with the inhabitants of southern France. They came ostensibly as liberators and continued to cloak themselves in this guise.

Simon certainly had not expected such a large army to march against him. His own forces consisted of his 270 trusted French knights, called by some the best cavalry in Europe, perhaps 600 other dependable armored horse, and a few hundred foot soldiers to defend the towns of southern France (Spaulding, pg. 338). He could not believe that Raymond of Toulouse had joined forces with the Spanish, either. Simon knew that he had to do something to stop the invasion or else he would be sorely put to deal successfully with it.

Hoping to force Peter to call off the invasion, Simon appealed to and received from the seven bishops and three abbots accompanying his small army a formal notice of excommunication directed at all Spanish and other generals who opposed the Crusaders (Sumption, pg. 165). Peter ignored the excommunication and continued his march northward, attracting large numbers of local militia, estimated by Vaux de Cernay to number an incredible 50,000 men! (Oldenbourg, pg. 165). Contrary to what some noted modern day military historians would have us believe, foot strengths in excess of 10,000 were considered exceptionally large in this period as leaders could not provide enough forage or command control to effectively use such a number of slow, unmaneuverable and unpredictable troops in battle (Verbruggen, pg. 145). Even so, it would seem safe to assume Peter had under his command close to 1,600 knights, 1,000 other cavalry and 10-20,000 foot.

During his four years in southern France, Simon de Montfort had not been idle. He had established a system of communications which included smoke signals, fire beacons and messengers (Verbruggen, pp. 292-293). Aware of Peter's movements, the Crusading leader remained in a position to move rapidly to the relief of whichever fortress the Spanish army directed its energies against. On August 30, 1213, the Spanish laid siege to the fortress of Muret, held by only 30 French Crusader knights and a hundred retinue-men (Oldenbourg, pg. 165).

Simon quickly moved to relieve the town, calling in the small garrisons within travelling distance. De Montfort had a good general's instinctive knowledge of the warrior psychology of moral faith in doing God's work, which his troops would need in abundance as the unequal battle loomed ahead. He stopped at the Abbey of Bolbonne, as Harold Godwinson had stopped at Waltham on his way to Hastings, and consecrated his sword to God, praying before his troops to God, "You have chosen me, though all unworthy, to fight your Holy war. Today I lay my arms upon your Alter, that when I join battle on Your behalf I may reap justice in this sacred cause" (Oldenbourg, pg. 165). With an army of 700 knights, the French commander rode to fight against the thousands of Spaniards and Toulousians who could not take the town of Muret before the Crusaders arrived.

Muret had managed to hold out because the Spanish army, encumbered by so many poorly disciplined, straggling foot soldiers and even slower militia, had taken over a week to finally assemble before the walls. Except for some perfunctory missile fire and piecemeal attacks by groups of unorganized Toulousian militia, the town remained unmolested. The besiegers presumably gathered enough drink and plunder throughout the surrounding countryside to spare the town until they could take it at their pleasure. They rested their forces, awaited more recruits and took their time, after all, their seemed no reason to hurry. The prevailing attitude among the Spanish and Toulousian leadership was that Simon would not dare to attack their army, led by Peter of Spain, one of the most renowned warriors in Western Europe.

But attack Simon did, marching an incredible 75 miles in 2 1/2 days (Spaulding, pg. 337). The Spanish had finally gotten around to launching a major assault on Muret on September 11, almost two weeks after their arrival. The attackers actually forced their way into the town and were pushing back the handful of defenders when Simon's army arrived, panicking the assaulters who fled back to their camp. Peter arrogantly proclaimed that it had been his battle plan all along to allow Simon to get safely into Muret so as to trap him there (Sumption, pg. 166).

Once inside Muret, Simon was startled to discover that only about a day's worth of food remained. The French bishops wanted to negotiate with the Spanish, as they feared the consequences of a battle with the overwhelming numbers of adversaries, but Peter refused their delegation, prompting a second group to go forth on the 12th, this time barefoot and penitent (Sumption, pg. 166). It is strange indeed to think that these same bishops, who had excommunicated Peter and his generals, expected a positive response... they apparently felt that their obvious penance would grant God's mercy upon their entreaties. Peter Tudebode noted that at the siege of Moissac, a procession of barefoot priests had attempted to intercede in the military developments as they had at the siege of Jerusalem (Siberry, pg. 91). The warriors must have felt that such an obvious penance would warrant God's mercy upon them. They were often wrong.

Peter used the negotiating truce to send some knights into Muret under cover of a missile assault on the northwest wall (Sumption, pg. 166). The Spanish commander had no qualms about using deceit, stealth or trickery to ensure his victory, even under a truce brought upon by God's own priests. They were quickly met by numbers of French Crusaders while Simon gathered the rest of his knights around him, including a contingent of brave Carcassonian knights who had ridden through the enemy lines during the night to join the Crusaders (Siberry, pg. 94). The remaining French priests heard their confessions and gave communion while praying for victory. Simon de Montfort refused to simply sit by and wait for Spanish assaults or starvation to destroy his army. He ordered his 900 knights to mount up and prepare to attack. His instructions to his troops were simple: "Do not stop to fight with the front line of the enemy, but press on, like Christian knights, into the enemy formations" (Verbruggen, pg. 91). The barefoot bishops were left to their fate.

In full sight of the jeering enemy outside the walls, Simon prayed, mounted his horse and received a final promise of martyrdom for any Crusader who died that day in battle from the remaining French bishop in Muret (Sumption, pg. 167). The Crusaders threw open a northern gate into the town, immediately drawing the attention of enemy leaders who assumed that their compatriots had succeeded in taking that portion of the town during the truce talks and had captured the gate. Simon led his knights out of the southern gate, appearing to be retreating and leaving Muret to the besiegers (Spaulding, pg. 337). The ruse worked. The jubilant cries of the Spanish and Toulousians were taken up by the whole besieging force and a mass of foot soldiers swarmed towards the invitingly open gate, expectant of spoils and pillage.

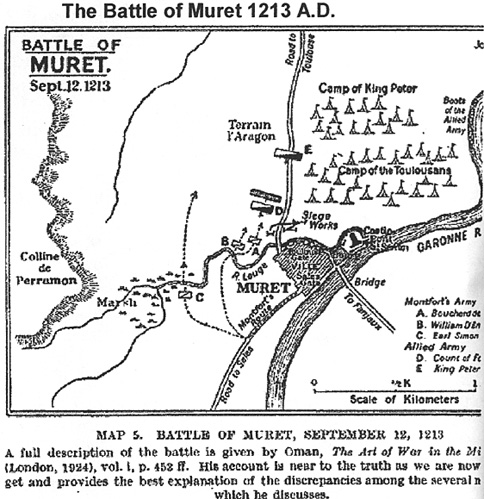

Simon's knights rode swiftly along the riverbank but instead of continuing south, they turned and rode north, cutting behind the masses of enemy foot and moving toward the nearest group of enemy knights, those of the Count of Foix. The startled Toulousians were eating as the French knights hove into view and barely had time to mount up before Simon's column of knights swiftly deployed into three divisions, one commanded by William of Contres, one under Bouchard de Marly and the third under Simon (Sumption, pg. 167). This intricate deployment, scoffed at or ignored by military historians intent on decrying any true 'art of war' in Medieval times, is illustrative of the command control which could be exerted by a powerful and resourceful commander in the field. With a lowering of lances, the French charged, smashed into the disordered Toulousians and immediately routed them.

Peter II was utterly exhausted on the morning of September 12, as the Crusaders destroyed the Toulousians. He had spent the night entertaining one of his many mistresses, but was alert enough to recognize the sound of battle and to realize that he was under attack (Sumption, pg. 167). As the Count of Foix's men were being swept away the Spanish in their main camp had perhaps fifteen minutes in which to prepare to meet the attacking French (Spaulding, pg. 341).

Simon shouted to his troops as they reordered their ranks and headed for the Spanish positions, "If we cannot drive them back from their tents, we have no recourse but to retreat instantly" (Oldenbourg, pg. 166). He knew that he would have one shot at breaking the enemy before overwhelming numbers could be brought to bear on his badly outnumbered force.

The main army of Spanish and Toulousian cavalry were camped upon a height, over two miles from Muret. Raymond of Toulouse wisely advised waiting for the Frenchmen to charge uphill, shooting them to pieces with infantry crossbow fire, and then counterattacking the tired survivors (Oldenbourg, pg. 166). Raymond's counsel was met with laughter and accusations of cowardice, the Spanish ridiculed the plan and advised Peter to test Spanish bravery versus French. Peter, bleary-eyed but ready to fight, switched arms and armor with a knight, as he desired to stealthily meet Simon in hand-to-hand combat. At 39, Peter was considered the finest warrior in Spain, and he would reap further honor and glory by a single-handed victory. As the Spanish mounted their chargers, the French continued to ride towards them.

Angry and bitter at being ridiculed and treated as an underling by the Spanish nobles, Raymond formed his Toulousian knights up behind the Spanish and awaited the results of the imminent Spanish-French combat (Spaulding, pg. 344).

Simon, watching the Spaniards forming up on the hill and considering the highly unfavorable odds of a frontal uphill attack against twice his own number of knights, decided to change his tactics. Letting the two division under Contres and Bouchard continue their advance toward the Spanish camp, Simon swung his own division of 300 knights to the right, aiming to cross a small ditch to the east of the Spanish army and thereby get into a position to attack the enemy left flank once they were engaged with the other French knights to their front. Peter, in the front rank of his disordered cavalry, was so intent on preparing his own attack on the French that he paid no heed to Simon's maneuver. As it was, the Spanish kept no orderly ranks, received no battle orders, and simply milled about, overly confident of their superior numbers and position, awaiting the French (Sumption, pg. 168).

As the French knights crested the hill, the Spanish finally charged, and the two forces crashed together, the noise of their collision, according to a contemporary, "...sounded like a whole forest going down under the axe" (Oldenbourg, pg. 167). Riding toward the ditch, Simon saw the Spanish knights attack his two divisions and watched as the personal standard of Peter II became engulfed in the maelstrom of individual knightly combat. Simon knew that if Peter's banner fell, the enemy morale would collapse and the French Crusaders would be victorious.

Suddenly Simon's force was at the ditch only to find an unexpected Spanish force guarding it. Simon spurred his charger ahead and, attacking uphill, knocked the Spanish commander from his horse, using his fists as he had broken a stirrup strap and dropped his sword in the charge (Spalulding, pg. 343; Sumption, pg. 169). The rest of the covering Spaniards fled. Simon now had a clear path into the exposed flank of Peter's main force.

Two French knights in the main French divisions, Alain de Roucy and Florent de Ville, had sworn an oath to kill Peter and managed to fight their way through to the hapless Spaniard wearing the King's armor (Oldenbourg, pg. 167). One of the French knights felled the imposter, crying "This is not the king! The king is a better fighter!" (Oldenbourg, pg. 167). Upon hearing this, Peter yelled back, roaring above the din of battle, "I am the king", and charged the Frenchmen, only to be surrounded and cut down by screaming Crusaders (Sumption, pg. 169). The Spanish household troops fought their way through to the fallen King, formed around Peter's body and were all killed, neither asking for nor receiving quarter. Death continued to be preferable to flight among the knightly consciousness of the 13th century, though it was not practiced extensively if other alternatives could be utilized.

Simon's command smashed into the flank of the wavering Spanish army which collapsed inward under the force of the attack. This unexpected attack coupled with Peter's death broke the morale of the Spaniards and the knights turned and fled, carrying Raymond's Toulousian cavalry, who had managed to stay out of the twenty minute melee, away with them (Spaulding, pg. 344). The battle was not yet over, however.

The Toulousian foot, attacking Muret, were convinced by the sound of battle that their much more numerous cavalry had beaten the French and caused them to flee. Though the French troops remaining in Muret had little trouble killing the poorly trained Toulousian militia and handful of knights who had managed to get through the open gate before it was shut, the thousands of militia continued to batter at the other gates, causing alarm throughout the few defenders desperately trying to keep the murderous mobs out. It was obvious to all of them, however, that sooner or later, superior numbers would prevail. They asked their bishop for help.

Bishop Folquet, the same man who had promised salvation for Simon's knights as they prepared to ride forth to battle, answered the French entreaties by ordering on the leaders of the besiegers to quit their attack and submit to the French (Sumption, pg. 169). The bishop had observed the results of the battle and wished to spare remaining lives. His order was ignored as the Toulousians continued their attacks.

Simon had managed to keep his personal troops under tight rein, allowing Contres' and Bouchard's divisions to pursue the routing enemy knights while his own division turned back towards Muret. The exhausted French knights mustered the strength for another charge and this time, drove into the packed masses of thousands of shocked militia, suddenly aware of the disaster suffered by their nobles. The foot soldiers, caught disordered and leaderless, tried to flee but could not escape their mounted pursuers. Thousands were cut down as thousands more, forced back to the river, drowned trying to swim across. Over half of the foot soldiers who had marched north with Peter II were slain as French troops poured out of Muret and joined in the slaughter (Oldenbourg, pg. 168).

Peter's body, already stripped by peasants, was later found and Simon de Montfort paid his respects to his adversary before returning to Muret, where he gave his horse and armor to the poor and went to church where he thanked his priests for praying for victory and to thank God for granting it (Oldenbourg, pg. 168). As the French foot killed the wounded Spanish and Toulousians, while looting the corpses, Simon, newly named 'The Flail of God', remained in church. William de Puylaurens wrote that "The Battle of Muret had an air of Divine Judgement about it", and the heretics were destroyed "...as the wind sweeps dust along the ground" (Oldenbourg, pg. 168).

The Albigensian Crusade Simon de Montfort vrs. King Peter of Spain: 1213 A.D.

Back to Saga # 98 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com