John A. Leavy, a Confederate surgeon, witnessed the fighting at Champion Hill on 16 May 1863. "Today proved to the nation the value of a general," he said. "[Lt. General John C.] Pemberton is either a traitor, or the most incompetent officer in the Confederacy." The Confederate defeat on this small rise on the Southern Railroad of Mississippi sealed the fate of Vicksburg, the Gibraltar of the Confederacy.

John A. Leavy, a Confederate surgeon, witnessed the fighting at Champion Hill on 16 May 1863. "Today proved to the nation the value of a general," he said. "[Lt. General John C.] Pemberton is either a traitor, or the most incompetent officer in the Confederacy." The Confederate defeat on this small rise on the Southern Railroad of Mississippi sealed the fate of Vicksburg, the Gibraltar of the Confederacy.

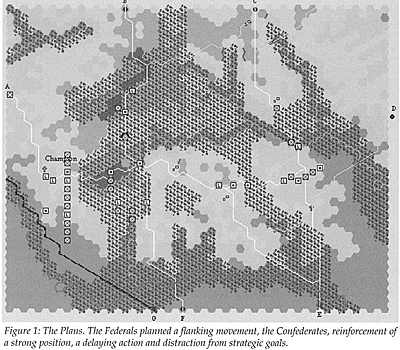

Figure 1: The Plans. The Federals planned a flanking movement, the Confederates, reinforcement of a strong position, a delaying action and distraction from strategic goals.

On 30 April 1863, Maj. General Ulysses S. Grant ferried 22,000 Federal troops across the Mississippi River at Bruinsburg, well south of Vicksburg. After crossing, he moved northeast toward the Mississippi capital at Jackson. From there, he planned to turn west, taking Vicksburg from the landward side.

Grant's crossing surprised the Confederates. Even though Grant's objective was clear, Pemberton, then commanding the Department of Mississippi, Tennessee and East Louisiana, dithered. He held his forces in Vicksburg until 12 May. By that time, Jackson was practically in Union hands. Two days later, the Federals put the city to the torch and turned west.

The danger posed by Grant's force was obvious to Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, the man responsible for defense of the Confederacy between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. He moved to Jackson from Braxton Bragg's headquarters at Tullahoma, Tennessee soon after hearing of Grant's crossing. "Major-General Sherman is between us, with four divisions" Johnston had written Pemberton on 13 May from a train station fifty miles from Jackson. "If practicable, come up on his rear at once. To beat such a detachment would be of immense value."

Pemberton's corps commanders agreed with Johnston's aggressive plan. Pemberton did not, remembering his orders from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to hold Vicksburg at all costs. He thought the plan too risky and, looking for cover, called a Council of War. He recommended a defensive position west of the Big Black River, near Vicksburg. When Johnston heard of the plan he was furious. On 15 May, with Jackson reduced to a heap of smoldering ashes, he expressed his thoughts to Pemberton. "Our being compelled to leave Jackson makes your plan impracticable. The only mode by which we can unite is by your moving directly to Clinton," a town on the railroad between Champion Hill and Jackson. Pemberton's corps commanders agreed with Johnston and Pemberton reluctantly moved east to meet the Federal threat.

Johnston's communications, laid beside Pemberton's actions, make Johnston appear the aggressive commander, Pemberton the bungling subordinate. In fact, neither Confederate commander performed well during this crucial period. Johnston expected 14,000 troops to be in the area by 14 May. These forces, coupled with Pemberton's and some timely interdiction of the Federal supply lines, could have changed the strategic picture significantly, if only Johnston had seized the initiative.

On the same day Johnston urged Pemberton to move east, he sent word to Richmond communicating his view of the situation. "I arrived this evening, finding the enemy's force between this place and General Pemberton, cutting off communication. I am too late." Instead of moving his forces at Jackson northwest to link up with Pemberton, closing Grant between two pincers, he turned northeast toward Canton and safety. He moved not only forces in the immediate vicinity out of harm's way, but also reinforcements coming from other commands.

Had Johnston massed his forces rather than dispersing them, he could have achieved numerical parity with Grant. Had he seized the initiative, he could have isolated Grant's vulnerable force. Deep in Confederate territory, Grant depended on a supply line stretching back to Grand Gulf, Mississippi. His food and ammunition needs alone required two hundred wagon-loads of supplies every day. Getting the supplies to Grand Gulf required additional wagon trains, which brought supplies sixty-three miles south from Milliken's Bend, LA, through treacherous bayous, patrolled by Confederate cavalry.

But Grant had a plan, and that was more than the Confederates had. Grant wrote of his Mississippi River crossing in his memoirs: "Vicksburg was not yet taken it is true, nor were its defenders demoralized by any of our previous moves. I was now in the enemy's country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object." Grant had seized the initiative. As tenuous as his situation was, he was confident of success.

Delay and bungling cost the Confederates everything. Pemberton's forces never united with Johnston's, and in J.F.C. Fuller's words, "The drums of Champion's Hill sounded the doom of Richmond." From Jackson, Grant hurried west and crashed into Pemberton's poorly deployed forces. By the end of the day, 16 May, the Confederates were streaming back to Vicksburg and ultimate defeat.

More Two Hard Weeks

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #40

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 2001 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com