I have written at length about offense in the OCS. This time, I will address the defense. I add this caveat now--I am an aggressive player; even my defense is liberally sprinkled with attack rhetoric and offensive stances. If you play a passive get-in-the-way defense, you might not agree with my methods.

The Purpose of Defense

Before we can adequately plan a defense, we must decide why we want to conduct one and what we mean to accomplish. There are four main reasons for defensive operations:

- 1) to halt active operations in preparation for future offensives,

2) to protect the flanks (or rear) of other friendly forces,

3) to delay (or stop) the advance of an enemy force,

4) to disrupt an enemy attack and provide an opportunity for counterattack.

These are all reasonable uses of a defense. All OCS defenses fall into one or more of these categories. Indeed, any good defense will likely consist of numbers 2 through 4. Number 1 is more specialized and may or may not have meaning at any one time.

In my mind, a good defense always consists of more than just holding back the enemy---one with that purpose alone is a defense, but is not a very good one. A better goal is to ensnare the enemy, partially separate his lead elements from his supports, and then counterattack vigorously to clean him out. The idea would be to allow him inbetween a series of strong point positions that are too strong to take down before your next turn and then to rip his forces apart using your own strong points as backstops-but then I am getting ahead of myself.

Unit Positioning

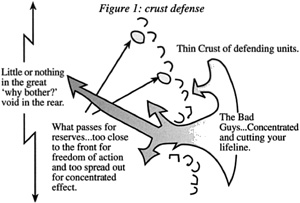

In Figure 1, you can see the most common defense found in wargames. Aside from a rigid crust, there is little to inhibit enemy breakthroughs once the crust is breached. Not by coincidence this is also the defensive stance taken by most gainers in their early OCS careers (by habit and training from other games). It is also the reason these players witness a catastrophic defense failure early on.

In Figure 1, you can see the most common defense found in wargames. Aside from a rigid crust, there is little to inhibit enemy breakthroughs once the crust is breached. Not by coincidence this is also the defensive stance taken by most gainers in their early OCS careers (by habit and training from other games). It is also the reason these players witness a catastrophic defense failure early on.

Unfortunately, after the dust settles, some never go back to see if they can do things better; these guys are convinced they had a perfect plan and that the system will not allow them to perform better. Luckily, most gainers are smarter (and less conceited?) than that. They go back, reevaluate what they did in the harsh light of failure, and strive to do better next time. For them, the whole effect is an eye-opening look at how many different styles they can bring to the table, each with its own pros and cons. In other words, they are intelligent enough to grow.

Some players get stuck into thinking they must cover every hex of the front with a unit. They live in fear of the system's lack of ZOCs and the fact that some enemy units might slip in behind their line. They are making two major mistakes.

First, covering every hex spreads the line thinly and evenly so that an enormous number of units cover the whole thing, leaving precious little for rear security. Meanwhile, they guarantee the enemy his choice of attack hexes, since all are equally weak.

Second, they mistakenly believe these dinky slip-through units are a threat; of course, given the lack of rear security, they might be. The first mistake is a waste of strength that accomplishes nothing. The second forgets that the enemy makes such incursions with units he will likely never see again, since you will destroy them. It will only take a few such losses before the enemy thinks better of wasting his units on limited-effect operations-of course, the more he sends off to die this way, the better off you might be.

With a decent web at the front (strong points established in decent terrain with reasonable strength and self-sufficiency), and posted reaction forces and main-line counterattack forces further back, this defense requires you to pay serious attention to rear area security. Since open terrain will cause the web to allow enemy units to slip between strong points (even encourages them to do so ... so they can be isolated and destroyed), you must garrison important rear facilities. Most players rapidly figure out they must garrison those rear dumps, HQs and airfields (not to mention key cities and the like).

However, old habits die hard and frequently a player loses a key location because he garrisoned it with the runt of the litter. Wargamers are pragmatic people and their games have taught them that the rear areas are nowhere near as important as the front and that a strong unit is wasted if in the rear. One of the basic principles of maneuver warfare (and warfare in general) is to be the strongest at the decisive point.

By ramming all their quality units into the front (possibly even in a crust defense), they place themselves in jeopardy. Gamersthink of the front as the decisive point, and sometimes it is. However, when your major supply depot falls without a whimper, you will find that the decisive point was not at the front after all, but in the rear where you left a crummy unit minding the store. Your good units, in true maneuver style, have been dislocated from the decisive point and rendered irrelevant.

Does this mean your garbage should be at the front and the quality units back in the rear guarding train stations? Of course not, use a mix. Those rear areas do not need an SS Panzer Division, but they do need more than a bush-league Hungarian Security unit. Give the important ones something with an action rating on it-you will be sorry if your prime HQ explodes because you thought a 2 could do the job.

When dealing with the compartmentalized terrain one sees in Tunisia, the web takes on a different look. Given the limited avenues of approach and the greater distances involved, the emphasis on counterattack changes. Limited counterstrokes over short distances are unlikely, so the counterattack strategy revolves more around major operations. You will move reaction forces less to hit then than to relocate for the next turn's counterstroke. Players can use terrain as a substitute for some strong points in their defensive web. Furthermore, the terrain allows a form of backstop compartmentalization. Small forces can hold deep mountain passes, allowing containment of any breakthroughs at the front.

The point here is that the web still exists in this sort of terrain, but it operates differently. I believe it is also easier to establish and execute-the terrain analysis is fairly easy and the demands on correct use of strong points and reaction counterattack forces is easier to decipher.

Careful establishment of reserves is key to the active portion of your defense. These reserves serve four functions:

The first is fairly evident to most OCS players and even novices prepare artillery reserves for this purpose. Take care in doing so, as a reserve marker might be wasted on some lone artillery unit that you could use more effectively elsewhere. Supplementing artillery in this job is the player's air force-provided the player was shrewd enough to keep an air reserve for such an eventuality. Once again, the use of supplemental air strikes to break up enemy attacks is obvious to even novice players-the difference between players at this point will be in the fact that the expert will have some air left to use, while the novice will not because he expended everything earlier.

Strict time constraints on reacting forces (they only have 1/2 movement and can only do overrun attacks) often mean that function number 2 is not possible. This being the case, I still attempt at every turn to have something available that might be able to do the job; a key overrun at the critical point might derail the entire enemy effort. Alas, the problem resides in the location and lines of movement available to the reserve. Getting an uncooperative enemy to allow everything to line up right is difficult, but I always want the option!

Function number 3 is of varying utility. When dealing with an enemy who must rely on hip shoot air strikes to DG his attack target hexes, you can slip anon-DG unit into the defense hex in this way. Not

only does this reaction force add to its halved defensive brothers, but it also adds a full-strength action rating to the hex. If conditions are right, you can turn what was easy pickings into a tough nut at the moment the enemy can do nothing about it. Given the right conditions, this is significantly easier to pull off than the overrun option above.

In other cases, where the enemy is relying on an artillery barrage to DG the target, the reaction force will show up just in time to get hammered like everyone else. While you can buck up the defense in this case as well (after identifying what the enemy wants), that reinforcement is watered down from the version above.

The last item is under-utilized by most players. Once the enemy has shown his hand and run into your web, you can take the Reaction Phase before your turn (you did make him go first, didn't you?) to reposition your troops so that the real counterattack (the one during your turn) has already begun to develop. Played correctly, this can save you effort in preparing for the next turn's festivities (the barbecue of the enemy units) and allow you to execute those actions with your units in Combat Mode. The player can use this phase as a bonus preparation round-provided he organized his forces to leave the option available. As always, the player with the most options will probably win.

Once through that initial Reaction Phase, presumably after at least limited luck in containing and disrupting the enemy incursion, players must realize that some units will go through the web line. However, these units will cause little real damage and, isolated on the friendly side of the web, will be easy to kill. The real counterattack portion of the web defense occurs after the enemy has done his partduring your own turn when you can put together a full mop-up operation. If your web performed correctly, the enemy will be subdivided throughout his depth by the remaining strong points (some will have fallen, but that is the price you must pay). Between the remaining strong points will be clusters of enemy units, some single unit stacks, and probably a lack of adequate supply and reserve stocks. Lastly, there will be a number of those deep penetration throw-away units.

The goal of the mop-up phase is literally to destroy every unit in the web or on the friendly side of it. These operations should consist of a layering of selective overrun attacks, key barrages, regular attacks (both from the forces working between the strong points as well as the strong points themselves), followed by final mopups in a fully utilized Exploitation Phase. Killing all the enemy forces is the goal, but plan for less than perfect results and do as much damage as you can. A good thrashing will cause the enemy to retire in terror even if his forces are not completely destroyed, but a destroyed unit is something you will not have to deal with again in the short term, so go for as many kills as you can get away with.

Even as the enemy limps away from the web after the mopup, the work of the defensive player is not over. I do not recommend following the retreating enemy in hopes of getting a few licks in before they completely recover. Such operations usually occur without much planning, generate limited results, and have a nasty habit of growing out of control into something the player did not intend at all. What you should do is repair damage to the web (rebuild strong points that received damage), upgrade the web (determine places that should have had a strong-point, but did not, or vice versa, to be ready for another attack), and move reserve forces to reestablish useful reaction forces for future attacks.

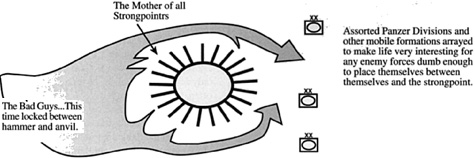

It is possible to use a large city as a breakwater in front of your lines. I have done this using Stalino in Enemy at the Gates. The idea is to make the city a fortress-many units and supplies, hedgehogs, and all the comforts of home. The city needs to be something that will take some serious effort to destroy. Next, place the mobile units that form the front with the rest of the web defense 3 to 5 hexes to the city's rear.

When completed, the breakwater can suffer momentary isolation without ill effect, but this is not much of a concern. Any

enemy force attempting to isolate the breakwater from its supports and trace supply will find themselves caught between the hammer of the mobile troops and the anvil of the breakwater itself.

Since the room between the two is small and the available time is insufficient, the enemy cannot insert a force between them that can fully resist the onslaught of the mobile reserves. The enemy has a dilemma-he can try to interpose himself between the breakwater and the mobile reserves (with quite possibly disastrous results) or he can station a line well before the breakwater that cannot hope to seriously attack the mobile reserves.

Barring unlimited resources, I have not figured out a good way to destroy this sort of defense--one must methodically reduce the breakwater first (very slow, very expensive, and not a little dangerous) from the side opposite the mobile reserves along a very narrow frontage. When confronted with this defense, I suggest attacking somewhere else to render it unimportant.

Most players (myself included) usually try to defend single-hex cities by occupying the city itself. That is the good terrain, right? If the troops are available (I know, a big IF), the best defense of a city is to defend the city hex and its six adjacent hexes. The adjacent hexes form the perimeter; the city forms the final fortress. There are numerous advantages to this sort of defense.

. The central city hex allows some units to be in reserve and is a reasonably safe place to put your dump.

The downsides of the perimeter defense are obvious-it ties up many troops and supplies that might be more useful elsewhere (all of which you are willing to write off as dead) and the best the defense you can hope for is to hold up the enemy for a time (eventually, it will fall). In specialized circumstances, you might find a stay-behind city force useful-if you do, try the perimeter version.

I believe I have made it clear that one should never look upon defense as some sort of Hitler-style "Barren Rot." Defense has a role and that role is more active and involved than simply getting in the way. A correctly run defense can entrap and destroy enough enemy potential to become decisive-certainly an offensive by your troops after an enemy disaster among your defensive works can spell victory in the game.

Putting together such a defense is difficult, and executing it correctly can be an excellent example of masterful play-your defeated opponent should shake your hand in congratulations at a job well done. It is a pity he will be too busy whining about his die rolls to do so...

More Enemy at the Gates Special Section

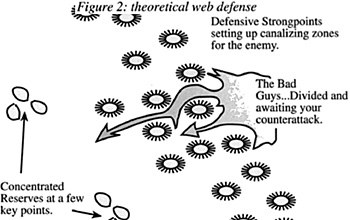

I prefer a more open web-like defense built on strong points arranged in a checkerboard fashion. In theory, I would like to establish this system with great depth-but resources do not allow one to build it that way. Generally, I set things up in a real game with a depth of about five hexes, with an occasional solid line of troops to act as breakwaters. The idea of the web is not to keep the enemy out, but to allow him to enter in a channeled and controlled way. To the enemy, it looks suspiciously like a trap---and it is one. Once in the web, the enemy will rarely be able to fully destroy more than a handful of strong points. Thus, during your next turn his troops will be spread

over a wide area with your strong points peppered throughout breaking his internal integrity. While Figure 2 shows the theoretical web across essentially open featureless ground, a real-game web would have its strong points based on good terrain and avenues of approach. In Tunisia, the possibilities are even better given the compartmentalized terrain-better for the strong points and channelization, but worse for your counterattack forces.

I prefer a more open web-like defense built on strong points arranged in a checkerboard fashion. In theory, I would like to establish this system with great depth-but resources do not allow one to build it that way. Generally, I set things up in a real game with a depth of about five hexes, with an occasional solid line of troops to act as breakwaters. The idea of the web is not to keep the enemy out, but to allow him to enter in a channeled and controlled way. To the enemy, it looks suspiciously like a trap---and it is one. Once in the web, the enemy will rarely be able to fully destroy more than a handful of strong points. Thus, during your next turn his troops will be spread

over a wide area with your strong points peppered throughout breaking his internal integrity. While Figure 2 shows the theoretical web across essentially open featureless ground, a real-game web would have its strong points based on good terrain and avenues of approach. In Tunisia, the possibilities are even better given the compartmentalized terrain-better for the strong points and channelization, but worse for your counterattack forces.

Reserves and Counterattacks

1) artillery to break up attacks,

2) units to launch overrun counterattacks,

3) units to reinforce hexes which expect attacks,

4) units to reposition themselves in preparation for the player's next move.Breakwaters

The result looks like Figure 3.

The result looks like Figure 3.

Point Defense of Single-Hex Cities

A Summing Up

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #20

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com