Game Design and Concepts: Joseph Hummel, Jim Rose, and John Tiller

Game Design and Concepts: Joseph Hummel, Jim Rose, and John Tiller

Programming: John Tiller

Game Graphics: Stephen Langmead, Joe Amoral, and Tim Kipp

Executive Producer: Jim Rose

Producer: Bob McNamara

Number of Players: Solitaire (against the computer) or 2-player (either by e-mail, null modem, modem, or the Internet).

Playing Time: Varies depending on the scenario, but can run several hours to half a day!

Complexity Level: Moderate

Packaging: Bookshelf storage box with full-color sleeve

Scale: Grand tactical to tactical. The player can command each of the individual battalions, regiments, and batteries in his army, or assign the computer to control them. Each hex on the map is 100 meters across. Each turn represents 15 minutes of real time.

Map and Playing Pieces: All components exist within the computer and appear in one of several different screens, menus, boxes or icons. The tactical units represent infantry battalions, or groups of 25 or more skirmishers, cavalry regiments or squadrons, artillery batteries, individual leaders and supply wagons.

Rule Book: 80-page softbound book with illustrations, historical notes, playing instructions, and technical support listings.

Scenarios: 21 total, including 11 "what-ifs"

System Requirements: Windows 3.1 or Windows 95, 100% IBM PC Compatibles, CPU 486DX PC or Pentium PC, 5MB minimum free space on hard drive, double speed (2x) CD-ROM required, 8MB minimum RAM, Microsoft-compatible mouse, 256 Color SVGA supporting 640/480, 800/600 or 1024/768 screen resolutions, all Windows-compatible sound cards

Publisher: TalonSoft, Inc.

Publication Date: 1997

Product Code: 1041097

List Price: $49.95

Summary: TalonSoft's Napoleon in Russia is the most impressive looking computer simulation of a Napoleonic battle that has been done to date. The breathtaking computer graphics are the strongest point of the game. The play mechanics are consistent with TalonSoft's preceding Battleground series, and are easy to learn. Anyone who has played any of the other TalonSoft games can start playing Napoleon in Russia almost immediately. An excellent variety of scenarios, including several "what if", up to the complete historical battle of Borodino (7 September, 1812), are provided.

Gorgeous Graphics

Napoleon in Russia's graphics are truly spectacular; the player gets the real look and feel of masses of troops on a Napoleonic battlefield. The map terrain is meticulously reproduced and extremely well done.

Napoleon in Russia's graphics are truly spectacular; the player gets the real look and feel of masses of troops on a Napoleonic battlefield. The map terrain is meticulously reproduced and extremely well done.

The designers have provided video clips from a re-enactment of the battle of Borodino. These clips are played during the introduction credits of the game and also after every artillery and infantry unit's firing sequence. Although entertaining to watch, these get old after repeated viewing; and they tend to slow game play. For faster play, you can turn off the video clips by using the "Options" pull down menu and clicking the check mark next to "Video Effects". (Any of the many game options can be turned off or on using this simple interface.)

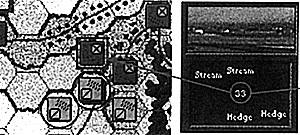

The map graphics can be viewed in six different scales, in 2D (two dimensional or flat view) and 3D look. 2D is similar to a board game as the units resemble square counters with either military or graphic symbols. For a bird's eye view of the battlefield, 3D shows units and the map in much greater detail -- depicted as miniature soldiers and actual terrain features. In either 2D or 3D you have the option to zoom in or zoom out; the 3D "normal" view (closest zoom) is recommended.

The hexagon grid overlaying the map can be turned on or off. Since units move from hex side to hex side, it is easier to see and understand this movement by leaving the hex grid on, although it detracted from the realistic look of the battlefield without hexes.

The hexagon grid overlaying the map can be turned on or off. Since units move from hex side to hex side, it is easier to see and understand this movement by leaving the hex grid on, although it detracted from the realistic look of the battlefield without hexes.

Game units are displayed and described in detail in boxes at the bottom of the screen. When you use the mouse to select a hex, all of the units contained within that hex will be displayed at the bottom of the screen. Each unit box contains a representative drawing of that unit (infantry, artillery, cavalry, leader), and information about the current state or condition of the unit. This includes its strength in number of men or guns, type of weapon, movement allowance, quality rating, formation (column, line, or square), and fatigue level. It also lists the name of the unit and its organization, such as its battalion number and parent regiment.

Competent Artificial Intelligence (AI)

While it is extremely difficult to get a computer to play a good game of chess, it is nearly impossible to get one to command competently in a complex Napoleonic simulation. The TalonSoft designers have done a better job at this than most other computer game publishers. This is not to say that they have developed a computer opponent that can beat a good or even average human player (no software designer to date has been able to do this), but the computer can give a good account of itself under certain circumstances.

The computer opponent in Napoleon in Russia is definitely better than the AI in TalonSoft's previous Waterloo game. The computer performs best when it functions on defense. The AI is competent at setting up a defense line, deploying its artillery, and using its cavalry in local counter attacks. However, it does not seem to know when to withdraw and as a result entire units are destroyed attempting to hold a position that should have been abandoned.

The computer gives a credible account of itself as the Russian player since the Russian army has only to hold to its positions to win. It is recommended that for a more realistic simulation play should be against a human opponent.

[TalonSoft comments that the AI tends to have units fight "to the death" because the designers felt that this is what happened (in general) during the actual battle. Having the Russians simply retreat every time they suffer heavy casualties would not be accurate: many units did stand and die stoically.]

Absorbing Game Play

Each daylight turn represents 15 minutes of real time while night turns are 1 hour of real time. Each turn consists of two player turns, Russian and French, with each player executing five phases: movement, defensive and offensive fire, cavalry charges, and melee. The player who is not moving or attacking may still fire defensively.

Combat losses and morale checks are resolved automatically and quickly by the computer; losses are deducted immediately and units are determined to be in good order, disorder, or routed. The sequence of play works well; it is easy to follow and can be quickly understood even by an inexperienced gamer.

To determine if a unit can fire at an enemy unit, an unobstructed line-of-sight must exist between the firing unit and its intended target. However, as in previous TalonSoft games, sometimes this line-of-sight can be achieved over the heads of friendly units. This is highly unrealistic for the Napoleonic period and it is recommended that you not fire in this way, even though the computer permits it (and the enemy AI will use it against you).

[TalonSoft agrees that for historical accuracy, players should not fire over the heads of their own troops. This ability to fire over the heads of friendly units is intentional, in order to make the AI more challenging; allowing such fire enables the computer to perform better.]

The sophisticated tools provided by the TalonSoft designers make the game mechanics run smoothly so you can concentrate on the strategy of game play. This is an important feature because few gamers enjoy being bogged down with cumbersome game mechanics.

Off Target As a Historical Simulation

Napoleon in Russia plays quite well as a general wargame; but as a historical simulation of a Napoleonic battle it falls short in some critical areas. In defense of the TalonSoft developers, the game plays as well and is as historically accurate as many of the Napoleonic miniatures rules and board games currently on the market. It certainly gives the look and feel of the Napoleonic era. The massed infantry battalions and cavalry regiments are impressive as they advance shoulder to shoulder across the screen, and the graphics depicting the fire of the massed artillery batteries are quite realistic and fun to watch.

However, the game presents several errors in fundamental aspects of Napoleonic combat. These mistakes, in turn, tend to encourage players to use non-historical tactics to achieve maximum results in the game.

For example, the use of skirmishers is an essential feature of the period and an area where the French had a tactical advantage. In the game, skirmishers seem to have much more success holding ground than they did historically: a unit of 25 skirmishers can stop a regiment of 1500 men from advancing into a hex! Historically, the skirmishers, facing 60:1 odds, would have simply fired and retreated before the advancing infantry in accordance with their doctrine.

[TalonSoft's response: We found that if skirmishers are deployed one hex in front of their parent unit, they work pretty well. It is correct that a battalion will not be able to go into melee in the same phase that its skirmishers sweep away those of the defender, but it will be able to do so in its next melee phase. TalonSoft is planning to add an optional rule to "displace" skirmishers, probably as part of the first upgrade. Formations of infantry will be able to push back skirmishers at a cost of an additional movement point, while cavalry will force them back at no additional cost. In both cases the relative sizes of the units will be taken into account, but these ratios have not been finalized. Nor has this idea met with universal acceptance among TalonSoft's testers, many of whom are Napoleonics buffs. A number of them see the main function of the attacking side's skirmishers as that of dealing with the defender's skirmish line. If advancing battalions can brush those enemy skirmishers aside, does that not make the attacker's skirmishers somewhat superfluous? And would that really be more historical?]

While infantry firepower casualty results seem to be modeled realistically, long-range artillery fire is woefully ineffective in the game. The inability of the artillery to cause significant casualties at long range encourages a clever attacker to use an unhistorical "walking wall of guns".

In a real Napoleonic battle, the artillery was usually set up between 800 and 1000 yards from the enemy, where, over the course of an hour or so, it inflicted tremendous physical and psychological damage on the massed formations of the period, softening them up for the inevitable attack to follow [this was the case at Borodino]. However, the attacker in Napoleon in Russia is rewarded if he limbers his artillery (even the heavy guns), advances them shoulder to shoulder with the infantry, unlimbers them at point blank range from the enemy formations, and literally mows them down.

Perhaps the most annoying twist is the turn sequence, which places the cavalry charge phase after the defensive fire phase. This gives the defender little chance to stop a cavalry charge from closing. The cavalry unit simply waits out of range during the defensive fire phase, then during the cavalry charge phase it rushes in virtually unmolested by enemy fire. The most vulnerable unit to these charges is artillery. It forces the player to stack infantry units directly with the artillery to prevent them from being constantly overrun by enemy cavalry. In one playtest game, the French captured over 200 Russians guns by taking advantage of this turn sequence. In the actual battle of Borodino the French captured only 9 to 12 guns.

[TalonSoft responds: Since supporting infantry can be as close as 50 yards to a battery, what's the problem with stacking them in the same hex and thereby protect artillery from this cavalry threat? (Hexes are 100 meters across.) One undocumented rule related to melee (omitted from the manual) is that whenever a unit advances into melee from within the Field of Fire of any unit defending in the melee, that melee attack receives a -1 modifier if that defending unit could have fired in the preceding Defensive Phase but did not. This represents final defensive fire immediately before the melee.]

Despite these shortcomings, TalonSoft's Napoleon in Russia is undeniably fun to play and impressive to behold. Purists may be frustrated that certain elements are inaccurate historically.

Despite these shortcomings, TalonSoft's Napoleon in Russia is undeniably fun to play and impressive to behold. Purists may be frustrated that certain elements are inaccurate historically.

Large Screen Shots (slow: 175K)

Hopefully, TalonSoft will one day produce the ultimate Napoleonic simulation on computer. Or, at least a higher level of accuracy for those who wish to learn how Napoleonic warfare worked.

[TalonSoft responds: NIR is a game, not a simulation. Hopefully, players will find our design enjoyable and evocative of the Napoleonic era of warfare. The reality of publishing a computer game is that certain compromises must be made. We may never be able to satisfy every Napoleonic expert. And, occasionally, we may respectfully disagree. Overall, however, we are flattered and pleased with the review and hope the readers of Napoleon magazine will give our games a try.]

Outstanding Game Support

This part of TalonSoft cannot be praised highly enough. No other computer game company supports their products and responds to user input as well as they do. For this reason alone TalonSoft products are highly recommended: the games perform as advertised, the company fixes the inevitable software bugs quickly, and they respond politely and quickly to the average user needs (this is unfortunately rare in the computer industry).

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #10

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com