Part I of this article addressed the organization of the U.S. Army during the War of 1812. This concluding article looks at the uniforms and equipment of these forces.

For a small force, the U.S. Army wore a wide variety of colors and styles of uniforms and in this way, mimicked on a much smaller scale the variety of uniforming found in Europe at the same time.

Factors which drove this variation were the frequent changes of regulation, the shortages of dye, the effects of the recruiting system, and finally the notoriously inefficient supply system. The results, on the wargame table, is a force in which every regiment could be uniformed differently with company variations within regiments as well.

The War Department updated uniform regulations in 1810, 1812, and 1813. These changes largely dealt with facing colors, cut of trousers, patterns of lace, and headgear for all branches. The shortage of blue cloth resulted in uniforms colored green, black, gray, white, and brown. All uniforms were cut and sewn in Philadelphia but it took months for the finished product to be moved to arsenals serving the military districts and months more for the uniforms to be transported by water and wagon to the troops on the frontier. It was not uncommon for troops to receive a new issue of clothing as long as one year after the regulation was first promulgated and by that time the next regulation was already in effect.

Compounding the problem was the manner of recruiting. As described in part 1, it was common for elements of a regiment to be serving in different areas, under different commands, and therefore draw their uniforms from different arsenals at different times. Arsenals issued what they had. When parts of a regiment reunited, it was common to see soldiers in different cuts and colors of coats and trousers and with differing head gear.

All that said, now let's examine uniforms one branch at a time.

Regular Infantry

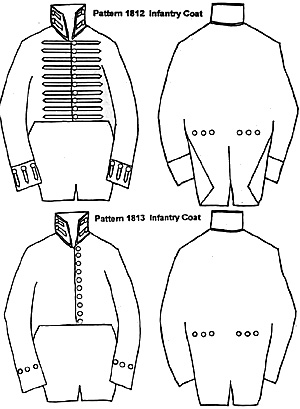

The uniform of most infantry at the beginning of the war was the 1810 pattern. The wool coat was blue with red collar, cuffs and turnbacks. Coat tails were short, extending to a point midway between waist and the back of the knee. The front of the coat was decorated with nine rows of white tape. The red collars had two buttons on each side and each of these buttons were connected to the front by a piece of white tape. There were no shoulder straps or shoulder boards except for officers and non-commissioned officers.

The uniform of most infantry at the beginning of the war was the 1810 pattern. The wool coat was blue with red collar, cuffs and turnbacks. Coat tails were short, extending to a point midway between waist and the back of the knee. The front of the coat was decorated with nine rows of white tape. The red collars had two buttons on each side and each of these buttons were connected to the front by a piece of white tape. There were no shoulder straps or shoulder boards except for officers and non-commissioned officers.

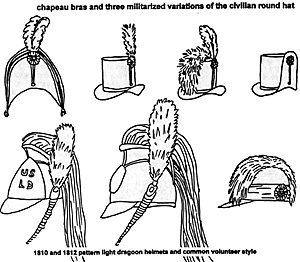

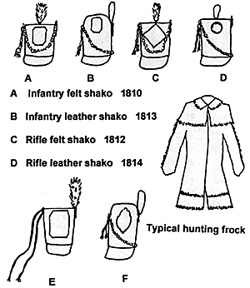

Head gear was a black felt cylindrical shako sporting a white plume centered at the front and a white tassel or cord from side to side and dipping in front over he cap plate which was of white metal. Officers wore a bicorn (chapeau bras) set fore and aft with a black cockade surmounted by a white plume.

Trousers (actually trouser gaiters) were closely fitting and white or blue. Cross belts could be either black or chalked white. Both colors of belts seemed to be used throughout the war. Knapsacks were a uniquely American design - painted light to medium blue with a white or red oval on the flap surrounding the letters U.S. in red or white. Blankets were kept in the knapsack, not rolled on top as was frequently seen in European armies. If there were no knapsack, both officers and men carried their belongings in a blanket roll over the shoulder.

Even at this time (and throughout the war), recruits were issued a simple waist-length linen coat of white or light gray without tape. The close fitting trousers were of white or unbleached linen. It was common for new soldiers to wear the recruit uniform for many months and even into the winter awaiting their more colorftil and warmer wool uniforms.

The pattern changed in 1812 but many troops did not receive this until the winter of 1812- 1813. This pattern changed the array of buttons and some modification to the tape on the chest. The big change was color. While the prescribed color remained blue, shortages of dye led to the production of coats of gray, black, brown, and drab (whose hue is unknown but suspected to be light brown or butternut) as well as blue. Some of the drab coats were faced with dark brown or green rather than red. Another change, the company-grade officers (lieutenants and captains) started wearing the shako while the field-grade officers continued with the old-fashioned bicorn. Musicians continued to wear red coats faced blue when available but some wore green coats faced in red.

In 1813, regulations changed in favor of a simpler uniform. The red facings went away as did the white tape on the chest. Trouser gaiters disappeared and were replaced by loose fitting pantaloons, almost always in white or medium gray. Musicians wore entirely red coats or red with buff collars and cuffs (captured British uniforms). Head gear changed also as the Army discarded the felt shako for the leather "tombstone" shako which was quite similar to the Belgic shako adopted by the British at about the same time. The white feather plume disappeared and was replaced by a white worsted plume now worn on the left side, over a black cockade.

The 1813 uniform appeared slowly and because there was a severe shortage of blue dyed wool (which was being bought up by militia and volunteer units) the War department also issued thousands of medium gray wool coats and overalls. Thus, the Army on the Canadian frontier had many regiments completely in gray or gray over white. Officers, however, bought their uniforms from tailors and therefore were always in regulation blue. Also, the new shakos were not necessarily issued the same time as the new coats and pantaloons so many variations of uniform are possible. It is the 1813 uniform that can be most easily converted from British 1812 figures. Simply remove the blanket from atop the pack and file off any wings or shoulder straps.

Militia and Volunteer Infantry

In the standing militia, many states prescribed a uniform similar to the pre-1810 regular infantry uniform. This sported red lapels as well as collars, cuffs, and turnbacks on a blue coat. However, usually only the officers bought uniforms. When federal or detached militia was called into service, it was not uncommon for them to be uniformed from an arsenal with whatever regular army uniforms were available. Since blue was reserved for the regulars, the militia wore medium-gray coats and gray or white gaiter trousers or pantaloons.

Very often the militia kept their civilian style round hats rather than adopting the shako. A round hat is what we might call a "top hat" and it carried any assortment of feathers, bearskin, cockade, and/or white metal cap plate. There is no evidence that militia ever wore the tombstone shako.

Very often the militia kept their civilian style round hats rather than adopting the shako. A round hat is what we might call a "top hat" and it carried any assortment of feathers, bearskin, cockade, and/or white metal cap plate. There is no evidence that militia ever wore the tombstone shako.

The pre-war volunteer companies wore an assortment of dress but blue coats faced red were most common. In 1812 these were amalgamated into ad hoc battalions, each company in a different uniform. As volunteer regiments were brought into federal service, they were either issued regular uniforms from arsenals or they procured their own distinctive uniform. Overwhelmingly this was the hunting shirt. The hunting shirt could be un-dyed linen or dyed black, brown, or blue. Typically the shirt was decorated with fringe in black, blue, yellow, or red. While the slouch hat was common, most frequently the colonel prescribed his men wear the civilian round hat with plume (white, red, or a combination).

Regular Rifles

The regular rifles started the war in two uniforms. The summer uniform was a long green hunting shirt (oft called a rifle shirt) with buff fringe and white gaiter trousers or overalls. The winter uniform changed during the war. In 1810 the green coat had black collars, cuffs, turn backs, lapels and shoulder wings. Gaiter trousers were green with black edging along the leg seam. The shako was similar to that of the regular infantry but with a green plume and yellow cords. Buglers wore a buff coat faced green.

In 1812 the coat lost its black lapels and wings. The front of the coat displayed black cord set in herringbone style. Yellow tape appeared on the collar similar to the regular infantry coat. Officers had gold epaulettes while NCOs had yellow. When the tombstone shako appeared in 1813, the rifles most likely adopted it. Because of the lack of green wool, the uniform was changed in 1814 to gray coats and overalls. Buglers in the 2nd , 3rd, and 4th Rifles were ordered into gray coats with black collars and cuffs while the 1st Regiment's buglers held onto their distinctive buff faced green for as long as they could. However, the gray uniforms didn't get to the troops until October or even later. The shako was changed also. The new shako was slightly bell shaped with a small circular cap plate, small green plume in the front, and yellow cords. It is most likely that many rifle units received this shako in 1814.

Militia and Volunteer Rifles

Rifle units were very popular in the militia and volunteers and the federal government issued thousands of rifles to these units. Most units wore the long, fringed hunting shirts (in a wide variety of colors) and therefore could not easily be distinguished from volunteer infantry except for their weapons. Riflemen in eastern states wore either shakos or round hats with green plumes while western state rifle units favored round hats (with red/white plumes) or civilian slouch hats. Western states also favored mounted rifle regiments and battalions while most eastern riflemen were dismounted.

Artillery

Artillery uniforms in 1810 and 1812 were identical to infantry uniforms except that the coat tails were longer, extending to the backs of the knees, and tape on the coats was yellow, not white. Artillerymen of the 1st Artillery Regiment wore the bicorne. with white plume while those of the 2nd and 3rd Regiments wore a shako with white plume and yellow cords. The 1813 pattern followed that of the infantry as well. Gone were the red facings and the only remaining tape was on the collar. Coat tails were shortened.

The tombstone shako with yellow cords and white worsted plume was prescribed but probably not issued until 1814. Due to lack of blue cloth, some artillery units received gray infantry style coats and pantaloons.

The tombstone shako with yellow cords and white worsted plume was prescribed but probably not issued until 1814. Due to lack of blue cloth, some artillery units received gray infantry style coats and pantaloons.

Also at right:

- E: Light Artillery Felt Shako

F: Light Artillery Leather Shako.

As stated earlier, the states along the Atlantic raised many militia artillery companies. Most evidence shows that these artillerists retained the long-tailed coats and bicorns of the regular army 1812 uniform rather than adopt the shako. Some militia companies sported the round hat.

Light Artillery

In 1812 the Regiment of Light Artillery wore an all blue coat with the buttons of the collar trimmed in yellow tape. Coat tails were short, like the infantry coat. Pantaloons were blue in the field and white for parade. The shako was slightly bell-topped with a large yellow metal cap plate and yellow cords. Officers sported an unauthorized blue sabretache trimmed in gold. Buglers were in red coats and most likely white pantaloons. Horse blankets for all were red edged yellow. In 1813, the regiment adopted the tombstone shako with yellow cord and, curiously, a green worsted plume at the left top.

Regular Light Dragoons

The regular light dragoons started the war in the 1810 pattern. The field uniform coat was all blue with silver shoulder wings for officers while the coat for the enlisted men was blue with red collar and cuffs. Both were trimmed profusely with silver (officers) or white (enlisted) cording on chest, collar, and cuffs. Buglers wore white coats with blue collar and cuffs. Breeches were white with a blue stripe, buff, or blue. Officer helmets were black leather helms surmounted by a bearskin crest and trimmed with a leopard skin turban band. Enlisted helmets were black leather with a high front piece and a long, white horsehair crest.

Dragoons didn't receive the 1812 pattern until late that year. The enlisted coat lost its red collar and cuffs which now matched the coat. The white cord trim on the coat was now blue. The officer coat was changed very little. The big change was the helmet. Both officers and troops wore the same black leather helmet. Gone was the high front piece and leopard skin. The helmet was reinforced with white metal bands and surmounted by a black comb and long white crest. Helmet plumes were white over blue except for certain officers whose color combinations identified their positions. Shabraques were blue with pointed comers and were edged silver or white. Valises were blue.

Volunteer Dragoons

At the beginning of the war, there was a wide variety of uniforms but as the war wore on, many states adopted the federal uniform as much as possible. Headgear was of two general types. The first was the black leather helm used by the regulars. The second was very popular among the volunteers. This was the black leather helm surrounded by a turban (in various colors) and topped with a crest of bearskin.

New York dragoons probably had the greatest variety of uniforms. The most popular was a red short-tailed coat faced in black with yellow tape around the buttonholes. At least one red-coated company had buff facings. A lesser number of companies wore blue coats faced red or buff and then there were a handful of units with green coats faced black. Needless to say, nervous militiamen often misidentified the red-coated dragoons as British.

Maryland dragoons and hussars favored blue coats with white lace on collars and across the chest with either style of helm. Virginia dragoons initially wore blue coats with red lapels and facings. The helm was the surmounted by a bearskin crest and surrounded by a light blue turban and finally decorated with a red over white plume. However, the state regulations were changed in mid-1814 to prescribe what was essentially the federal uniform.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of uniforming from a wargamers point of view is that almost any uniform combination from the wide variety described above is possible. Regular units wore whatever was available in the arsenals and militia and volunteers often designed their own uniforms despite state regulations. In my own 1812 army, no two regiments are in the same uniform. And that, frankly, is part of the appeal of America's Napoleonic war.

American Army of War of 1812: Part I (MWAN #99)

Back to MWAN #99 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com