Introduction

This is the second half of an article on a forgotten "bad neighborhood" of the American frontier--a place just right to use as a setting for an Old West skirmish scenario or short campaign. Part I appeared in MWAN # 105.

Below you will find detailed, game-relevant information on the history, economy, and landmarks of the region surrounding the town of Canyon Diablo; and some information on the area today. Together it is enough to create an integrated and historically accurate venue for Wild West gaming at the skirmish level. Compress the history a bit, drawing on the elements you like to construct scenarios which--while they may provide wilder single days than occurred even in Canyon Diablo--will at least have as their foundation the real life of a once-real town.

Early Indian Presence

The Apache and Navaho tribes had used the area around Canyon Diablo as a battleground for centuries before the white man arrived. An ancient, well-marked Navaho trail from the north passed over the bleak mountains of the Mogollon Rim via Chavez Pass, then clung to the east side of the canyon along its full length.

Spanish Influences

Hopi guides led members of the Cardenas Expedition to the spot in 1542; these Spanish soldiers may have given the canyon its imposing name. A century and a half later, Don Diego de Vargas came north with a great expedition to put down a general uprising of Indians in New Mexico. Vargas then put the reconquered Indians to work hunting mercury, silver, and gold for him. It was during this period that a legend concerning the "Lost Mines of the Padres [Mountains]" began to be circulated. By the time Canyon Diablo sprang up, the legend was quite elaborate; a number of prospectors passed through town from the east on their way to "find" the mines. (Men still seek them, in a wide area west and north of the canyon.)

The Americans Arrive

The first American citizens in the Canyon Diablo region were beaver trappers who appeared in the late 1820s. They came mostly for the water that lay in pools in the bottom of the canyon, even when the Little Colorado River to the north.

In

about 1850, pack train traders--forerunners of established trading posts--serviced the

Navaho families living in and around Canyon Diablo. Some of the most prominent pack

train traders were former fur trappers who had been forced to adapt their livelihoods

when the demand for beaver pelts dried up. (These hardy independents included Billy

Mitchell, "Whitehead" Fitzpatrick, Gabe Hall, "Old Man Yellowface" Buck, and a former

Navaho adoptee the Indians called Billikona Sani (Old American).)

In

about 1850, pack train traders--forerunners of established trading posts--serviced the

Navaho families living in and around Canyon Diablo. Some of the most prominent pack

train traders were former fur trappers who had been forced to adapt their livelihoods

when the demand for beaver pelts dried up. (These hardy independents included Billy

Mitchell, "Whitehead" Fitzpatrick, Gabe Hall, "Old Man Yellowface" Buck, and a former

Navaho adoptee the Indians called Billikona Sani (Old American).)

They tended to travel together for mutual protection. Different groups periodically held rendezvous on the rim of Canyon Diablo. The traders peddled bullet molds, gunpowder, indigo and cochineal dyes, flints, beads, and cheap steel knives in exchange for buffalo robes, horses, mules, and handmade silver jewelry. The most popular white man's trade good was rotgut whiskey, usually concocted on the spot of one part raw alcohol, three parts water, Cayenne pepper for bite, and chewing tobacco for color. The most common Navaho offering was a striped woolen blanket measuring about 36 by 80 inches; these sold readily to would-be emigrants back East as "wagon blankets".

For the balance of the 1850s Santa Fe traders laid out wagon roads across north- central Arizona, while various US Army officers were kept busy surveying possible routes for a transcontinental railroad. The most unusual of these survey groups was led by Lieutenant Edward F. Beale of the U.S. Topographical Engineers, who hit Canyon Diablo in 1857. Beale packed most of his rations and other on camels. The animals had been brought in through the Gulf ports of Texas, and were handled by expert camel drovers from Greece and the Arabian Peninsula. Unable to pronounce their true names, the American members of Beale's expedition called the drovers "Greek George" and "Hi Jolly" [Hadji Ali], respectively. After the Camel Corps was dissolved, both men settled down in Arizona, gaining considerable local fame as pioneers.

Clashes with Indians

One of the first armed clashes between the US Army and Indians in this region occurred on the Navaho Trail on 18 April 1867. Companies B and I of the 8th US Cavalry Regiment, under the command of Captain J.M. Williams, killed 30 unidentified Indians when they made a stand near the site on which the town was later established.

In 1868 and again in 1869 Apaches assaulted Beaver House, a stockaded

trading post recently established by Herman Wolf. Wolf and his Mexican employees

repelled the raiders, though not without loss to themselves. (Apache raids on Wolfs

post continued sporadically throughout the 1870s. By 1880, however, the Navaho

population had largely rebounded from the low point it had reached as a result of the

tribe's forced resettlement by the Army in 1864 (the infamous Navaho "Long Walk").

An increase in the number of teenage Navaho males helped to deter further Apache

raids.)

In 1868 and again in 1869 Apaches assaulted Beaver House, a stockaded

trading post recently established by Herman Wolf. Wolf and his Mexican employees

repelled the raiders, though not without loss to themselves. (Apache raids on Wolfs

post continued sporadically throughout the 1870s. By 1880, however, the Navaho

population had largely rebounded from the low point it had reached as a result of the

tribe's forced resettlement by the Army in 1864 (the infamous Navaho "Long Walk").

An increase in the number of teenage Navaho males helped to deter further Apache

raids.)

On 26 September 1869, cavalry from Camp Verde encountered a large party of Apaches near the barranca crossing of the canyon (see below). Loaded with loot, the Indians were returning south from a raid on Navaho country: in the subsequent action 36 Indians were killed, 12 captured, and one soldier was wounded. A very similar encounter began near the same place on 8 June 187 1, as a result of which Troops A, D, and G of the 3rd Cavalry killed 56, wounded eight, and captured 10 Indians in a two- day running fight.

In late 1874 Apaches destroyed a small wagon train some miles north of the later town site, near the military road. About 28 persons were killed and their bodies burned, along with the looted wagons. No one knew the identity of the members of the train, which was apparently headed for Prescott; no one was reported overdue.

Regional Economy

The (legitimate) economy of the region surrounding Canyon Diablo was built around cattle and sheep ranching, cheese making (!), lumbering, and freighting. John Wood brought in a herd of cattle from New Mexico in 1877, grazing them a few miles north and west of town. In those days, the present red clay flats were covered with grass sod thick enough to sustain large animals. August Helzer, a large-scale stock operator from Utah, arrived with another herd soon thereafter. These men were the two biggest names in cattle ranching in the period 1881-1882. Several smaller fry, of course, followed in the wake of the railroad. Extended droughts in California in the early 1870s brought a number of sheep owners into the area. John Clark, the first large sheep rancher, drifted in with 3,000 head in 1875; he grazed his flocks in the valleys north of Canyon Diablo during the summer and fall. William Ashurst arrived in 1876, occupying ranges south of town. In the early 1880s two brothers, J.F. and W.A. Daggs, raised more than 10,000 sheep at two extensive camps situated north of Clark's.

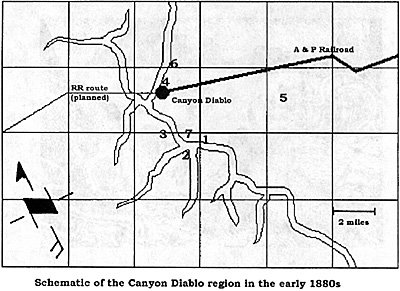

LandmarksRefer to the following map of the area immediately surrounding the town of Canyon Diablo. (Some details of this map, and of the accompanying descriptions, have been deliberately altered to discourage illegal and potentially dangerous treasure-hunting.)

Map

Schematic of the Canyon Diablo region in the early 1880s

Schematic of the Canyon Diablo region in the early 1880s

1. Massacre of the Padres (Site Approximate). In 1769 unidentified Indians attacked a party of Franciscan padres and its escort of Spanish soldiers, headed east from the mountains of north central Arizona to their church headquarters in Santa Fe. The fathers led a number of mules loaded with bars of silver that had been mined for the church. A running fight forced them south and west; they abandoned mules one by one as the latter were killed or fell behind. The Spanish finally made a stand at the edge of a crevasse still known as Padre Canyon [Reference Point 11, a subsidiary of Canyon Diablo. They allegedly cached the bulk of the silver on the site of an abandoned Indian village nearby. The party split up that night, five of them attempting to escape west toward California and the other five cast toward New Mexico. Apparently only the latter group survived. (In 1902, a long-lost document and associated map were discovered in the archives of the San Miguel Mission, Santa Fe, which together shed considerable light on this incident. A swarm of treasure-hunters subsequently descended on the area, uncovering some 18th-Century decorative armor and a 64-pound silver bar in Padre Canyon in 1919. These articles were believed to have been lost from a pack mule before the main cache was made.)

2. Apache Death Cave. Navahos cornered an Apache raiding party in this cave in June 1878. Some 20 Apache warriors under Crooked Jaw (Naiche-son of the great Cochise) had disappeared into it with their horses after sacking a cluster of hogans in the Melgosa Desert and abducting three young Navaho girls. At that time the only entrance to the cave, which was located in a side canyon directly behind the future settlement of Two Guns [see below], was almost completely concealed by a natural stone bridge. A Navaho scout discovered the Apache's secret by accident when, crawling forward to reconnoiter from the canyon rim, he felt cool air rising through a tiny fissure and heard Apache voices below.

Navaho reinforcements soon trapped the Apaches in the cave; riflemen were posted on the canyon wall opposite to make sure none escaped. Negotiations aimed at securing the release of the three girls broke off, for the latter had already been raped and killed. At length the Navaho dropped heaps of tinder-dry brush inside the cave mouth and set them on fire, in an attempt to smoke the Apaches out. The latter, knowing their fate should they emerge, hung on grimly: they even slit their ponies' throats, hoping the skins full of blood they collected could be used to douse the flames. Their every attempt failed. Toward evening, smoke began to drift up even through the surface fissures; the Apaches (except for Naiche, who with two companions had luckily ridden south before the ring was closed) sang their death songs.

The rocks around the cave entrance did not cool off until the following noon. When the Navaho entered the cave, they found that the Apaches had dismembered the corpses of their ponies and tried to stuff the pieces into the cave entrance as a barrier against the smoke. The resulting wall of barbecued horseflesh had to be punched out with poles. The twisted bodies of a dozen Apaches, partially desiccated, lay sprawled on a natural stone platform in the first (main) room of the cave. Five more were found in the next room, the narrow passageway to which was completely blocked with asphyxiated humanity.

Altogether some 40 Apache men and women, along with the three Navaho girls, had lost their lives in the cave. The siege put an end to its use by the Apaches; indeed, no raid was ever again launched against the Navaho from that quarter.

The Apache Death Cave was explored to a distance of almost four miles at an early date possibly while the town of Canyon Diablo was still a going concern. Two amateur speleologists from Winslow subsequently mapped seven miles of passage; in the mid- 2011, Century two more miles were added by breaking through a wall at one point. In the early 1960s, a rockslide between the fifth and sixth rooms blocked access to all but the first 500 feet.

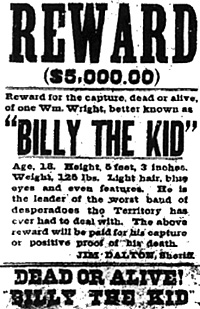

3. Hideout of Billy the Kid.

3. Hideout of Billy the Kid.

Sheep rancher Bill Campbell had begun to construct a stone building, laid in mud mortar, on this site in 1878. Taking over the unfinished walls the following year, the infamous outlaw Billy the Kid (William Bonny) and his gang completed the building with a flat roof and attached night-holding corral. They then set about rustling horses and mules to fill it. The Kid and his gang drove a band of stolen stock here from New Mexico during the winter of 1879-1880. The same work stoppage that was responsible for the creation of the town of Canyon Diablo, however, soon dried up the local market for contractors' teams. The Kid and his cohorts were only able to barter a few head to local Navahos before giving up and heading back toward New Mexico. The stolen animals themselves, now in embarrassing surplus, were shot en masse in the flats west of Winslow.

4. Narranca Crossing

This crossing of the canyon was being used regularly long before 1850. By the early 1880s hundreds of names had been inscribed in its low stone walls; the earliest legible one, in Spanish, is dated July 1830.

5. Meteor Crater

A mass of superheated iron and nickel weighing several million tons impacted the Earth at this spot about 22,000 years ago. Chunks of rusty meteoric iron, thrown off by the impact, dot the landscape for a mile or two west of the deep, oblong gash. In 1886 Fred W. VoIz, proprietor of a Navaho trading post in what was left of Canyon Diablo, hired some Mexicans with wagons to collect a quantity this ore: Volz had found a man in Los Angeles who was willing to pay him 75 cents a pound for two flatcar loads. Only after the ore had been shipped did Volz commission a formal assay; this revealed that each pound of meteorite contained two percent platinum, nominally worth $36. The Flagstaff Weekly Champion touted the crater as "...[possibly] the world's richest mine." Volz's claim to the rock was promptly jumped by others, who eventually hauled out tons of it: jewelers alone would pay $25 per pound.

(During Canyon Diablo's heyday the local name for Meteor Crater was Coon Hole; today it is known as Barringer Crater.)

At about the same time bucktoothed prospector Adolph Cannon, a recluse who overwintered in the caves north of Canyon Diablo, discovered that a slatelike matrix within the rock occasionally contained small diamonds that could be broken out with a hammer. While he kept the existence of the meteoric diamonds to himself for many years and never acted wealthy, exaggerated tales began to spread about valuable caches of diamonds Cannon had supposedly placed about. He is believed to have been murdered for his knowledge of their locations in about 1918. (A gravel hauler discovered Cannon's skeleton, shot twice through the head, in 1928. Shortly thereafter a burly man staggered into a line camp near Jack's Canyon, one of Canyon Diablo's innumerable subsidiaries. Dying of a gunshot wound, he had with him a buckskin pouch filled with diamonds of a rough industrial quality. He said that he and a partner had found one of Cannon's diamond caches, over which they had argued. The partner was dead a result; the unidentified man died enroute to a Winslow hospital. Two of the cowboys to whom he had told his story promptly grabbed the diamonds and caught a train in the direction of California, never to be seen again)

6. Buried Loot (Site Approximate)

In the years that followed the collapse of the town proper, trains were robbed at Canyon Diablo Station several times. Four cowboy-drifters from Hashknife pulled off the most spectacular of these heists on the snowy night of 21 March 1889. The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad's Express No. 7 had stopped at Canyon Diablo for water. Promptly Jack Smith, "Long John" Halford, Dan Hawick, and William D. Starin leaped aboard and dragged the engineer and fireman out of the cab. Blowing open the train's safe, two of the bandits grabbed a metal box containing $100,000 in currency; also in the safe were $40,000 in gold coin, 2,500 newly-minted silver dollars, a number of fancy pocket watches, and a quantity of jewelry. They then rode away toward the south, along the canyon rim.

A posse led by some experienced trackers in the pay of Wells, Fargo Co. were soon pursuing them. Eventually all the robbers were captured and thrown into the Prescott jail. Each of the four was sentenced to 25 years; none served his full term, however, before being pardoned late in life. Strangely, at the time of their arrest the group of bandits possessed no more than $100 between them.

What happened to the rest of the take? After his release, one of the bandits blabbed that on the night of the robbery they had doubled back to the north, swinging wide around the ruins of the town, in an attempt to throw off pursuit. They then stopped and divided the coins and currency on the canyon rim, burying their rifles, the fancy watches, and the jewelry under some nearby cedar trees. With that, they lit out separately for Texas. It is unknown whether any of the bandits returned for the loot after being pardoned, or whether they could have found the cache(s) again. It had been pitch-black and snowy, after all, none of the cowboys knew the area very well, and the landmark cedar trees had been cut down for firewood soon after they all went to prison. Men have sought this fortune ever since.

7. "Fort Two Guns."

In 1925 one "Indian" Miller built a gaudy tourist trap he called Fort Two Guns alongside Route 40, a few miles from the former site of Canyon Diablo. Miller operated a "lion farm", restaurant, and curio shop on this site for five years. He cleaned out the first two rooms of the Apache Death Cave and built fake Cliff Dweller ruins inside; the Apache skulls he discovered he sold to tourists as souvenirs. Large piles of other remains- pony and human-he disposed of via a Winslow bone dealer. Miller also built a "model" Hopi pueblo directly above the cave entrance; from it Indian women in his employ sold bright pink loaves of piki bread. Two Guns' screaming promotional billboards blighted the scenery for miles around until indignant neighbors tore them down.

Miller, who was part Mohawk, claimed to be a full-blooded Apache Indian and billed himself as "Chief Crazy Thunder". He fought a long (and ultimately unsuccessful) legal battle with the widow from whom he leased his spread at Two Guns, claiming that the land was in fact his, and made a nuisance of himself in other ways. (Some thought it was only poetic justice when a mountain lion Miller kept for display in his zoo very nearly clawed him to death. A year later, a Canadian lynx practically disemboweled him. He was even bitten on the finger by a Gila monster, the toothless jaws of which are normally harmless. But the wound became infected, and it took six months for the swelling--which extended to Miller's shoulder--to fully subside.)

He left the state one step ahead of the sheriff in 1930, only to inflict a similar operation on New Mexico.

Canyon Diablo in Decline

Canyon Diablo in Decline

As mentioned in Part I of this article, the town of Canyon Diablo fell into instant ruin in late 1882 once railroad construction resumed, taking most of the town's population with it, Only the railroad depot and its immediately- supporting buildings remained in regular use; the rest of the cheaply-made structures fell early prey to the elements, salvage parties, and accidental fires . For a time, fly-by-night businesses were operated out of a few of them. By the turn of the 20th Century, however, the region was practically empty of people. Two Guns revived and grew a bit in the 1950s and 1960s; for lovers of real Western adventure, however, it will always be overshadowed by the foot-high ruins of Canyon Diablo.

Selected Sources

Bancroft, H. H., History of New Mexico and Arizona (New York:

Bancroft Co., 1888, later repr.).

Espinosa, J. Manuel, The Expedition of de Vargas into New Mexico

(Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1940).

Fulton, Maurice G., ed., The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid (New

York: Macmillan, 1927).

Hegemann, Elizabeth C., Arizona Trading Days (Univ. of New Mexico

Press, 1963).

Lockwood, F.C., Arizona Characters (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times

Mirror Press, 1928).

Marshall, James, Santa Fe: The Railroad That Built an Empire (New

York: Random House, 1945).

Moody, Ralph, Old Trails West (New York: Thomas Crowell Co.,

1963, later repr.).

Richardson, Gladwell, Two Guns, Arizona (Santa Fe: Press of the

Territorian, 1968).

If you liked this article, see also Painted Sunset (Stenhouse Game Productions, 1998 (stenhousegames@hotmail.com) , the author's booklet of historical miniatures scenarios of Army-Indian conflict in the Old West.

Back to MWAN #106 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com