Series Overview:

Almost everyone with an interest in the Wild West has heard of such legendary '"Vide open towns" as Abilene, Virginia City, and Deadwood. This article is the first in an occasional series on the forgotten bad neighborhoods of the frontier-places just right to use as settings for an Old West skirmish scenario or short campaign. Most such towns arose practically overnight, in response to a specific event--a land rush, the arrival of a railroad, or the discovery of silver nearby, for instance. They tended to decline or disappear just as quickly once this motivating event had played itself out, or another "big thing" caught on elsewhere-luring away the population that made the town viable.

The brief but violent heydays of the towns and regions I shall describe in this series offer you, the historically- minded miniatures gamer, so much "meat" for scenariobuilding that you may never go back to the generic, often slapstick gunfight actions we have all had to get used to. This is in keeping with my firm belief that, if judiciously sifted, the record of actual towns such as Canyon Diablo readily suggests scenarios at least as dramatic and playable as any hastily- contrived shoot-'em-up.

In this two-part article you will find detailed, game-relevant information on the layout of the town of Canyon Diablo, its history, population, and more colorful personalities, as well as a description of the history, landmarks, and economy of the surrounding region. Together, it is enough to create an integrated and historically-accurate venue for Wild West gaming at the skirmish level. Compress the history a bit, drawing on the elements you like to construct scenarios which-while they may provide wilder single days than occurred even in Canyon Diablo--will at least have as their foundation the real life of a once-real town.

Origin of the Town:

Canyon Diablo (Devil's Canyon) was a child of the rails. In mid 1881, construction of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (later the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe) was halted at the eastern rim of a 250'-deep, sheer-walled rock canyon in north central Arizona. Westward progress of the road drifted into limbo as the railroad company underwent reorganization--a process that took more than a year to complete. In the meantime some 2,000 railroad surveyors, construction engineers, Irish, Mexican, and Chinese laborers, sutlers, and their hangers-on waited out the resulting financial fits and starts in the high desert. Until late 1882, when the railroad company recovered its footing and bridged the canyon, Canyon Diablo was one of the least wholesome places in the American West.

Location:

As days of inaction turned into weeks, then months, some the construction gang's pitiful tarpaper and brushwood shacks gave way to slightly more permanent habitations. The resulting "instant town" was located near the halfway mark between Flagstaff and Winslow, AZ, just off what is now Interstate Highway 40 (at the southwest corner of the great Navaho/ Hopi Indian Reservation).

Layout:

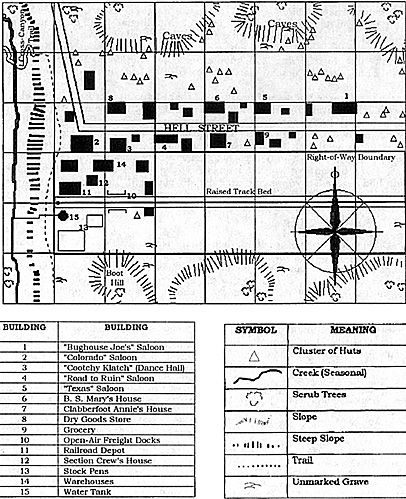

The following is a conjectural diagram of Canyon Diablo's "town center" and its immediate environs. One square measures approximately 50 yards across.

Canyon Diablo eventually stretched nearly a mile, eastward from the yellow-painted depot at the canyon's rim, along the north line of the railroad right-of-way. Near the depot itself, on railroad land, were the section crew's house, stock pens, a large water tank (filled by pump from a thin, seasonal stream on the canyon floor), freight docks, and warehouses. Just to the north two lines of buildings sat facing each other across the main thoroughfare, perhaps 20 yards wide, which was called Hell Street. Along this dusty, rocky track stood 14 saloons, 10 gambling dens ("poker flats"), four houses of prostitution, and two dance halls which proved to be only slightly more respectable than the bawdy houses themselves. Wedged among all these were several tiny open-air eating counters (forerunners of today's fast-food establishments), a grocery, and a dry goods store. None were particularly substantial buildings, being only one story tall and made of tin, tar paper, and canvas nailed over frames of unseasoned lumber. A few actually bore names on their drab, unpainted false fronts.

What passed for "metropolitan" Canyon Diablo was a strip perhaps 350 yards long nearest the canyon itself. While it indeed featured an unusually high concentration of shacks, it had practically none of the other amenities we today associate with a town. Among the motley collection of clip joints were the saloons "Colorado" and 'Texas", the "Last Drink", the "Road To Ruin", "Bughouse Joe's", and the "Name Your Pizen". The main dance hall was the Cootchy-Klatch, whose painted hags doubled in the bordellos.

The town's two favorite houses of prostitution faced each other across Hell Street and were owned, respectively, by Clabberfoot Annie and B.S. Mary (the initials mean what you think they do). Both joints were noted for the steady stream of pretty and oncepretty women who passed through them, some of whom ended up married to local stockmen. Notwithstanding her unappealing nickname, Clabberfoot Annie was a fairly handsome woman who had an hourglass figure when she was wearing her corsets and silk. B. S. Mary, by contrast, was a buxom, rawboned bawd who stood about six feet tall. Both had a taste for redeye, and were usually plastered. The two sodden madams bickered constantly, bellowing insults at one another across the dusty expanse of Hell Street. Often, provoked beyond endurance, they would rush together and begin a gouging, hair-pulling melee. [1]

Canyon Diablo's business proprietors, their families (a few had unwisely been sent for), and their principal staffs probably lived on the premises of their establishments. In addition, each of the 14 saloons no doubt boasted a dirt-floored back room which several men would rent by the night, or week. Some men may have been lucky enough to score places in the tenders, boxcars, and cabooses which were trundled to and from town. Almost everyone else seems to have inhabited clusters of tumbledown shacks, wagon beds, and Indian-style wickiups scattered throughout the broad area behind each row of Hell Street buildings. [2] Hard-core privacy types set up in one of the small caves which the wind had scoured in nearby hill faces. [3] Finally, the truly down-andout simply spent the night under the stars.

Almost as remarkable as the "amenities" Canyon Diablo did boast are the ones it did not. For example, although its population was fairly large by frontier standards, Canyon Diablo had not a single church. Likewise, no one was foolhardy enough to try to open a bank. [4] Finally, there is no evidence that a separate doctor's office existed. Routine medical treatment was probably administered at home, in accordance with time-tested old wives' remedies, supplemented now and then by the minstrations of transient medical men. More severe cases were shipped east about 30 miles to the railroad division hospital at Winslow.

Getting There and Away:

Freight wagons passed north along the eastern rim of the canyon toward an old, switchback crossing which descended to the canyon floor, then painfully climbed the other side. Other rough-and-ready wagon routes fanned out from town in several directions. Canyon Diablo served as the railhead for Flagstaff, Prescott and other towns to its west and south. Freight trains hauled sawmill and mining machinery, saloon potables, and miscellaneous merchandise into Canyon Diablo; in addition, short passenger train runs were made daily from the yards at Winslow. Finally, a regular stage line operated between Flagstaff (the stage headquarters) and Canyon Diablo.

Public Safety:

During its brief but violent lifetime even Tombstone, AZ could not hold a candle to Canyon Diablo for sheer depravity. Murder on the street was common. Holdups occurred almost hourly; vulnerable-looking newcomers were liable to be slugged on the mere suspicion that they carried valuables. Not only stagecoaches, but train cars were robbed by impromptu gangs of footloose drifters who had originally come west looking for a place to settle.

The death rate was high. The town's Boot Hill, some distance south of the tracks, held 35 marked graves. [5] The Hill did not by any means, however, contain the bodies of everyone "put away" at Canyon Diablo: scattered north and south of the tracks were the graves of untold numbers of nameless murder victims, buried where they were found.

In Canyon Diablo, one changed ownership of a saloon or gambling parlor by the simple expedient of gunning down the current claimant to title. That was how one Keno Harry obtained his place in 1881; it was also how Boot Hill obtained Harry, the following year.

Constant plundering of wagon and rail traffic in the region made Flagstaff merchants and Canyon Diablo saloon owners see red. Even wagonloads of sawmill machinery and replacement parts were damaged beyond repair by bandits enraged to find nothing among the freight which could readily be turned into cash. E. E. Ayer, whose lumber mill at Flagstaff was the largest in the American southwest, managed to get his machinery through with the help of an escort of soldiers from Fort Defiance. The troops' intermittent presence was of little real concern, however, to the town's criminal element.

At length the sawmill owners and Flagstaff merchants banded together to offer a good salary to any man willing, as Marshal of Canyon Diablo, to keep outlaws under control: the town fathers at end-of-track had only to hire him. This proved considerably more difficult than finding the money had been.

The town had a rapid succession of peace officers. The first one pinned on his badge at three o'clock in the afternoon; at eight the same evening he was laid out for burial, The second lasted two whole weeks. The third was a sneaky-looking character who toted a sawed-off shotgun. Three weeks into his term as Marshal, while blasting an outlaw, he also managed to pepper several (relatively) innocent bystanders. Soon thereafter, a disgruntled man--either a victim of this mishap, or a relative thereof-put several slugs between the lawman's shoulder blades. The fourth town Marshal was a gnarled little fellow with piggish, black eyes who attempted to guarantee his personal survival by cutting a deal with the outlaw element. He served for nearly a week before the victim of some bandit, whom the Marshal had refused to arrest, ambushed him at point blank range in the dark.

Weeks passed; the office of Marshal stayed vacant. Finally in rode a sallow-cheeked, consumptive ex-preacher from Texas who sported two low- slung revolvers. The hiring committee, standing outside Keno Harry's poker flat, propositioned him forthwith. Broke and hungry, the stranger accepted. When asked his name for the record, he hesitated; then, glancing down at the striped poplin ducking range pants he wore, he replied that they could call him "Bill Duckin" Duckin lasted thirty days. During that period he killed an average of one man per day, and wounded so many that for a while, the railroad hospital at Winslow refused to accept any more gunshot victims.

On his very last Sunday morning, "Duckin" strolled toward Ching Wong's Beef Stew Counter for breakfast. Flush with money after putting the squeeze on all the joints, he had discarded his eponymous canvas pants and decked himself out much more fancily. Imitating more famous marshals of the day he had bought a pair of black, two-button bobtailed coats. One was for Sunday wear. The other, his "everyday" coat, had the side pockets cut out so that he could shove both hands down, grasp the butts of his pistols, and swing their barrels up between the coat edges (Duckin's holsters hung on swivels and had their bottoms lopped of]). While in office, he used

this trick to plug one bad actor after another: the last thing they saw on Earth was Duckin placing his hands contemplatively in his pockets. This day, confronting a bandit who had just robbed the Colorado Saloon, Duckin ordered him to surrender. Too late, he realized he had on his Sunday coat. The bandit opened fire, and Marsal Duckin lost his job (along with a couple of quarts of blood).

[6]

Duckin's successor was "Fighting Joe" Fowler--a man who had already tamed the roaring railroad town of Gallup, NM, killing 20 men in gunfights. "Fighting Joe" lasted just 10 days, however, before he rode unannounced back to New Mexico. During that time he had narrowly survived three separate attempts to bushwhack him.

In light of the mortality rate among Canyon Diablo peace officers, neighboring Yavapai County refused to furnish any of its own men to maintain law and order there. Desperate, Flagstaff businessmen finally appealed to Territorial Governor Frederick Tirtle for help; Tirtle demanded that the US Army step in to restore order. The Army moved with its habitual slowness, however, and before plans could be laid for the establishment of martial law in town, the presence of troops became unnecessary. In late 1882 the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad was recapitalized, the gorge abutting Canyon Diablo was quickly bridged, and the road resumed its long march westward to California. The rip-snorting town of Canyon Diablo died overnight.

Selected Sources:

Kildare, Maurice, "Keno Harry" (Real West magazine, January 1967).

Marshall, James, Santa Fe: The Railroad That Built an Empire (New York: Random House, 1945).

Moody, Ralph, Old Trails West (New York: Crowell Co., 1963).

Richardson, Gladwell, Two Guns, Arizona (Santa Fe: Press of the Territorian, 1968).

Notes

[1]Occasionally one of them managed to tear off every shred of clothing the other wore, much to the delight of spectators. Once, Clabberfoot Annie is known to have pumped two barrels' worth of birdshot into B. S. Mary's broad behind as the latter turned to flee.

[2]When representing the town's outskirts on the wargames table, liberally sprinkle them with rocks (a few of which would have been large enough to provide cover in a gunfight), sagebrush, stands of cactus, crude outhouses, and ramshackle stock pens. There should also be one or two vital, deep-drilled water wells. Land NOT on the railroad right-of-way will have most of the physical "improvements".

[3]One can imagine the warren of little rooms and reach-spaces a little elbow grease could have produced within the sand cliffs, Most such digging would probably have been done after dark, both to avoid working in the heat of the day and to hide the extent of its progress from prying eyes. Indeed, prehistoric Indians had already proved that in this part of the country inain could extend the precincts of a natural shelter cave for several dozen yards (at least) into a cliff face without bracing, while, leaving the entrance no larger, than a coyote's hole.

[4] Instead, saloons seem to have served as the main "sale depositories" and moneylending establishments. In the latter role they were no doubt supplemented by a small but influential complement of loan sharks.

[5] A gravestone made of blue granite memorializes the only man buried on Boot Hill who was known to have died peacefully. Herman Wolf, a prominent local trader, passed away in September 189(-- long ftcr the rest ofCanyon Diablo had vanished. The only woman ever buried on the Hill had once, worked in Clabberfoot Annie's house. One morning, she was found with her throat slashed--allegedly the work of one of B. S. Mary's girls, who had mistaken the victim's crib for that of Annie, herself.

[6] Duckin's fate might have served as an object lesson to gunslingers who chose to rely on tricks, rather than a fast draw and sure aim. In general, if the trick didn't work even once, such men had little to fall back on and were doomed.

Back to MWAN #105 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com