HISTORICAL OUTCOME

Before the Patriots' dazzled eyes, Howe's entire army fanned out in battle array. It was

quite a show: an officer in Webb's regiment later recalled, "...A bright autumnal sun shed it

luster on polished arms; the rich array of dress and military equipage gave an imposing

grandeur to the scene, as [the British] advanced in all the pomp and circumstance of war."

Before the Patriots' dazzled eyes, Howe's entire army fanned out in battle array. It was

quite a show: an officer in Webb's regiment later recalled, "...A bright autumnal sun shed it

luster on polished arms; the rich array of dress and military equipage gave an imposing

grandeur to the scene, as [the British] advanced in all the pomp and circumstance of war."

Presently a column consisting of seven foot regiments, some cavalry, and artiIlery--about a third of Howe's force--broke away from the British left and headed northwest, toward the Bronx River. The remaining British soldiers simply sat down in their places: Howe had no intention of risking massive casualties for an objective he thought he could gain just as easily by committing only part of his army. The resulting fight at Chatterton's Hill was thus played out before a critical audience of some 10,000 military professionals, and an even greater number of rebels.

Shaking out into line, the Hessian vanguard declined to cross the swirling Bronx River, which was found to be choked with deadfall and the remains of old beaver dams. The Germans began building a rude bridge of felled trees and fence rails to get over. The British II Brigade, however, found shallower going a little farther downriver and plunged in with a will. The highest casualties the British and Hessians were to suffer all day were inflicted by a rebel battery under CPT Alexander Hamilton, which raked the riverbank as clusters of dripping-wet enemy surmounted it.

The British and Hessian field artillery quickly went into battery atop a small hill located about half a mile from the rebels' right-center. The Germans then began a sheltered march toward the enemy right flank; although Haslet and Smallwood made an effort to contest this movement, it was completed with only minor loss. Meanwhile, Leslie's British brigade made a premature thrust up the tangled slopes of Chatterton's Hill at the rebel left; to everyone's surprise, the leading British elements were stopped cold by Webb's regiment. Pieces of British regiments trotted back onto the flat to re-form; and since Leslie's artillery had by now ceased firing for fear of hitting its own men, the Patriot defenders cheered what they thought was a victory.

At that instant, however, the Hessian Brigade and British Light Dragoons (whom the rebels had lost track of in the deep shadow below the crest of the hill) lashed up through less obstructed terrain on the western slope. The tiny rebel militia regiments on that side fired one ragged volley, then fled, uncovering the Patriot center. Smallwood himself was twice wounded; his regiment soon fell into disorder. Hamilton's artillery battery was already out of the fight: an enemy cannonball had disabled one of its guns and mutilated a single crewmember, putting the rest to flight.

The remaining Patriot units scrambled back across the hill and down its rough northern slope. Enroute, some turned the numerous walls and fences on the crest into temporary strongpoints. Only the Delaware Regiment remained firm throughout, despite having lost three of its companies: at one point the "Blue Hen Regiment" was the only formed Patriot unit on the field.

The British and Hessians advanced slowly, inspecting every hayrick and fenceline for snipers. The Americans thus had plenty of time to get away: Haslet's men even managed to drag off Hamilton's remaining serviceable gun. The retreating troops were met by a detachment from Putnam's Division, which arrived too late to be of much use.

"The pomp and circumstance of war" had claimed about 250 men (killed or wounded) on each side. While technically defeated, the American participants congratulated themselves on a job well done. Recriminations flew, however, between the British and Hessians. As the historian Steadman put it, "The (British) victory, being obtained, was not followed by a single advantage."

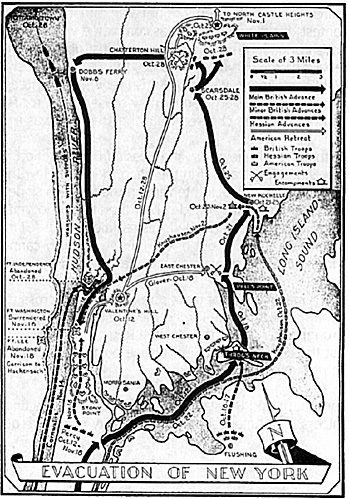

For several days the opposing armies glared at each other within a long cannon shot. The British fortified the northern slope of Chatterton's Hill. Impressed by the apparent strength of Washington's main entrenchments protecting White Plains, Howe waited for Lord Percy to bring up reinforcements before making a push against the rebels' line. When Percy arrived, however, bad weather delayed the assault once again. The night before it was finally to be delivered (I November), Washington pulled back to the strong lines he had prepared at Castle Heights. Howe gave up and turned his army southwest to reduce Fort Washington.

Notes

[1] Various parts of Howe's army were punished in at least three sharp skirmishes on their slow march northward. At Haarlem Heights (16 September), Washington's men saw British regiments retire before them for the first time. The Queen's Rangers, under the heretofore highly-regarded Robert Rogers, lost 80 men when the Delaware Regiment surprised it at Marmaroneck on 21 October. Riflemen commanded by COL Edward Hand routed 240 Hessians at East Chester two days later.

[2] The affected contingent included a second Grand Division of 4,700 German mercenaries, as well as 3,400 inexperienced British recruits.

[3] In practical terms, from the perspective of the American entrenchments this creates a "dead

zone" perhaps 3-6" wide at the base of the Hill. This shadowing effect works both ways. The fire of any figures located in the woods themselves onto the flat (and vice versa) is not affected.

[4] It is suggested that formed units be assessed some cumulative penalty in Disorder for each turn they spend traversing the water.

[5] It makes for a more interesting game if mounted stands are permitted to cross these Field Works, but at a heavy movement penalty.

[6] Each of the two batteries shown in the British order-of-battle is the equivalent of four 12-lbr. field guns. This rating reflects in part the contribution of a "Grand Battery" that Howe drew up some distance south of White Plains to support the first stages of Leslie's move to the British left.

[7] Patriot command arrangements for this battle were somewhat confused. Arriving with his brigade on 27 October, McDougall assumed formal command of the odd assortment of units (previously under Haslet) which Washington had posted to Chatterton's Hill within the previous 48 hours. Haslet, however, seems to have commanded something more than his own regiment. The Unit Roster given here shows the most probable division of responsibility between the two men.

[8] The requisite Line of Retreat must be at least 8" wide and cannot exceed 36" in length.

[9] The only other militarily significant objective shown on the map is the western edge of the village of White Plains. Even if captured, however, the latter probably could not have been held if Chatterton's Hill were still in rebel hands.

[10] For simplicity's sake, only artillery capable of throwing shot of six pounds' weight or greater is routinely represented in HHW.

[11] In a few cases, ratings based on these generic categories have been adjusted up or down to account for units' unusually poor (or steady) performance at White Plains.

More Battle of White Plains: 28 October 1776

Back to MWAN #106 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com