Vittoria is a shallow valley about eight miles

broad and ten miles long, lying within steep

fences of girdling hills.

Vittoria is a shallow valley about eight miles

broad and ten miles long, lying within steep

fences of girdling hills.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Vittoria (very slow: 295K)

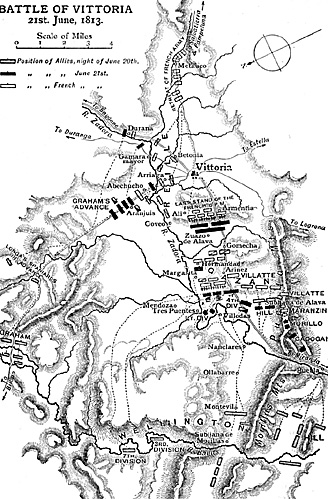

The town itself is at the eastern end of the valley. A wall of rugged hills -- the Puebla range -- bounds it on the south; a parallel range serves as a wall to the north. To the east, where Vittoria stands, these ranges meet in a sort of apex, while a range of hills called the Morillas serves as a western base to the triangle of hills, within which lies the scene of the great battle.

The Zadora, a narrow stream with deep banks, bisects the triangle, running from Vittoria in the east straight down to the base of the western hills, then swinging round at right angles to the southern range, and finding an escape through a deep and wild defile which breaks the angle where the Morillas and the Puebla ranges meet; thence it flows into the Ebro The valley has, roughly, the shape of a bottle with the town of Vittoria as the cork. The royal Madrid road runs from the Puebla pass up the left bank of the Zadora to Vittoria and thence it forms the main road to Bayonne and to the Pyrenees. This constituted Joseph's line of retreat.

Joseph's army, 70,000 strong, filled the valley with the glitter of arms. Their first position was on a low ridge that crossed from north to south in front of the village of Arinez, and commanded the valley of the Zadora with its seven bridges. So confident were the French in the overmastering fire of their guns, that they did not break down these bridges -- a fatal blunder. A second and loftier range, on which stood the village of Gomecha stretched from the Zadora to the Puebla range; and still higher in the rear rose the town of Vittoria itself.

Behind the French lines was the plunder of fifty provinces, vast convoys of waggons and carriages, the whole court equipage of Joseph, camp-followers, Spanish officials, the wives and mistresses of French officers, &c. A French prisoner after the battle said to Wellington, "Le fait est, Monseigneur, que vous avez une arince, mals nous sommes un bordel ambulant!" Loud, distracted, and far-heard was the tumult of men and horses and carriages hurrying with dust and clamour eastward, along the great causeway which runs towards the Pyrenees into France.

The French, it must be remembered, had been plundering Spain with French method and thoroughness for more than five years, and they were now practically submerged beneath their own booty. Convoys laden with the accumulated plunder of a hundred cities were being eagerly pushed on France-ward. But the time was short, Wellington was near and eager to strike. And it was plain that if Wellington broke the French lines and drove Joseph's divisions in flight back on this vast and ill- ordered crowd, the neck of the "bottle" -- as we have called Vittoria would be hopelessly "plugged."

Wellington's Tactics

Wellington quickly determined on his tactics. He once more, with a haughty confidence both in his own genius and in the fighting quality of his troops, adopted a plan which, in its excess of daring, violated the canons of military art. He determined to win the battle as he had won the campaign, by the stroke of a great captain's skill rather than by the actual push of bayonets. The obvious plan was to cross the Zadora, break through the French centre, and push with fiery resolution straight on to Vittoria, thus not only shattering Joseph's army, but cutting off his left wing. But this would have cost 10,000 men, and Wellington counted a bloodless victory more glorious than one red with slaughter. He made the plan of the battle a copy in little of the strategy of the whole campaign. Graham, with the left wing, consisting of 18,000 men and twenty guns, was to push round the northern wall of the hilly triangle and seize the great road to Bayonne in Joseph's rear. Hill, with the right wing, was to break through the Puebla pass and thrust the French left from the heights.

Wellington understood French character. The sound of Graham's guns rolling sullenly over the hills, and past the French right, would put an almost irresistible pressure on the French imagination. That thrust at their communications would act like the prick of a lancet on the nerve of a limb. It would shake the whole French army almost into dissolution.

Then when the French centre had been weakened to sustain the fighting on either flank, Wellington himself, with the British centre, would break through on their front, and drive Joseph's whole army back in ruin on Vittoria. And if Graham actually succeeded in seizing the great road to Bayonne, the French retreat would be flung aside on to the marshy roads to Salvatierra.

Audacious Strategy

It meant that, in the presence of an enemy of equal strength and holding a central position, Wellington divided his forces and attacked at three remote and independent points, in country so wild and rugged that no communication could be maintained betwixt the British columns.

June 21, the day of battle, was a Sunday -- the longest summer day of the year. It illustrates the uncertainty of history that the experts contradict each other flatly as to the manner on which that day of fate dawned.

Napier, who was not present, says, "The morning was rainy and heavy with vapour." Leith Hay, who was present, riding in Wellington's staff, says, "The morning was extremely brilliant; a clearer or more beautiful atmosphere never favoured the progress of a gigantic conflict."

The aspect of the battlefield was curiously brilliant. The stern hills on either flank, narrowing as they approached Vittoria, defined the scene of the conflict perfectly; and as the two positions held by the French rose in steps one above the other, their whole battle, with its "magnificently stern array," was visible at a glance.

L'Estrange describes how the sight of this great army of enemies impressed the imagination of a young soldier, looking on his first battlefield. Henry, in his " Events of Military Life," says that as he stood with his regiment in the British centre on the crest of the Morillas, they caught their first glimpse of the whole French army in the order of battle, with the roofs of Vittoria sharp-cut against the horizon beyond their masses.

The French front was betwixt five and six miles in length, the troops in column, the artillery clustered upon every summit. He draws a graphic pen-picture of the rival hosts.

"The dark and formidable masses of the French were prepared at all points to repel the meditated attack -- the infantry in column with loaded arms, or ambushed thickly in the low woods at the base of their position, the cavalry in lines with drawn swords, and the artillery frowning from the eminences with lighted matches; while on our side all was Yet quietness and repose. The chiefs were making their observations, and the men walking about in groups amidst the piled arms, chatting and laughing and gazing, and apparently not caring a pin for the fierce hostile array in their front."

But this represents only the scene at the centre. Graham's columns had moved at dawn, and, curiously enough, the French remained long in ignorance of that deadly stroke at their communications.

Hill, two hours after Graham had started, leaped with such suddeness and speed on the Puebla gorge the shoulder of the great range rising sheer on his right, the Zadora with its rocky bed to his left that he was through the pass before the French could offer serious resistance; and he at once sent Morillo, a Spanish leader of known daring, with his brigade, to push the French off the flanks of the Puebla range, and so roll back their left wing. The hillside was so steep that the men seemed to climb rather than to march. Spanish valour is of eccentric quality, but at this moment it was in its highest mood.

Morillo's lines swarmed up the rocky ascent, pushing back the French with steady volleys till the actual crest was reached. Then the French charged with the bayonet. They had the advantage of the ground; they met the Spaniards with a fury through which ran a flame of scorn, and the Spanish line was flung in ruin down the hilly slope, Morillo himself being wounded, but refusing to be carried off the ground.

Hill, watching the struggle keenly, sent the 71st, under Cadogan, and a battalion of light infantry, into the fight. Cadogan was a soldier of the finest type. The night before the battle he had been what his Highlanders would have called "fey" -- in a mood, that is, of curiously exalted spirits -- at the prospect of taking part with his regiment in one of the great battles of history.

Charge

He led his men magnificently forward, the pipers shrilly blowing "Hey, Johnny Cope, are ye waukin' yet?" The slope was steep. The smoke blew thickly in their faces, and through the smoke flashed incessantly the darting flames of the French musketry. Fast fell the men; and yet the cool and disciplined lines never faltered. Up to the crest-their officers leading-and over it, the Highlanders went, and the French were driven headlong from their position. But the long wooded flank and the steep summit of the hill were strewn with the dead; and, as one survivor records, "there were 300 of us on the height able to do duty out of 1000 who drew rations that morning."

Amongst the slain was Cadogan, and his best epitaph is found in a sentence which Wellington himself wrote to his brother the next day. "My grief for the loss of Cadogan," he wrote, "takes away all my satisfaction at our success."

While Hill's musketry fire was thus sparkling fiercely on the black slopes of Puebla, and far off in the east Graham's guns could be heard in deep waves of sound, Wellington commenced his attack on the bridges which crossed the Zadora. The river at that point forms a sharp loop; the bridges were small and close to each other.

A Spanish peasant brought the news that one of the bridges was unguarded, and Barnard's Rifles were at once sent forward to seize it. The men came on at the double, with rifles cocked. The bridge was crossed. Up a steep curving white road to the summit of a low hill crowned by an old chapel the Rifles pressed, and found themselves almost within musket-shot of the French centre.

A French battery fired two round shots at the little group of Barnard's men, who stood for a moment visible on the crown of the bill, and one of these slew the peasant who had guided the British across the river.

Next came the whole of Kempt's brigade. They crossed the bridge and formed under the shelter of the hill. "Our post," says an officer who was present, " was most extraordinary, as we were isolated from the rest of the army, and within ioo yards of the enemy's advance. As I looked over the bank, I could see El Rey Joseph, surrounded by at least 5000 men, within 500 yards of us." But the French still made no move.

The 15th Hussars followed over the bridge in single file, came up the steep path at a gallop, and dismounted in the rear of the Rifles. Some French dragoons now came up at a leisurely pace to see what was going on below the ridge, but a few shots from the Rifles drove them back.

The 3rd and 7th divisions were now moving forward to attack the bridge of Mendoza. The French batteries opened upon them, and a strong body of French cavalry was brought up in readiness to charge the head of the British column the moment it crossed the bridge. But Barnard, who was already (as we have seen) across the river, took his Rifles at a run betwixt the river-bank and the French guns and cavalry, and smote them both in flank with a fire so sharp that they fell back, and the Mendoza bridge was carried.

The story of Picton's part in this movement has in it an element of grim humour. Kincaid, who belonged to the Rifles, had already caught a glimpse of the famous leader of the "Fighting Third."

"Old Picton," he says, "rode at the head of the 3rd division, dressed in a blue coat and a round hat, and swearing as roundly all the way as if he had been wearing two cocked ones."

Picton Takes Charge

But, somehow, the order to move had not reached Picton. The battle thundered to right and left; some of the other bridges had been carried, but the 3rd was apparently forgotten. Picton's fighting blood was up; his anger at receiving no orders grew furious.

"Dit!" he said to one of his officers, "Lord Wellington must have forgotten us!" He rode to and fro in front of his men, watching the fight, fuming to plunge into it, and beating the mane of his horse angrily with his stick, An aide-de-camp, riding at speed, came up, and inquired where Lord Dalhousie, who commanded the 7th division, was. Picton, in wrathful tones, declared he knew nothing of Lord Dalhousie; were there any orders for him?

"None," said the aide-de-camp.

"Then, pray, sir," said the indignant Picton, "what orders do you bring?"

The aide-de-camp explained that Dalhousie was to carry the bridge to the left, and the 4th and 6th divisions were to support the attack. The "Fighting Third" in brief, were to look on as spectators while other divisions did the work! Rising in his stirrups, Picton in tones of passion shouted to the astonished aide-de-camp, "You may tell Lord Wellington from me, sir, that the 3rd division, under my command, shall in less than ten minutes attack the bridge and carry it, and the 4th and 6th divisions may support if they choose."

Then turning to his men, who were chafing for the fight, he cried affectionately, "Come on,ye rascals! Come on, ye fighting villains!" And, let loose with those paternal epithets, Picton's fighting villains "promptly carried the bridge.

The spectacle of Picton's charge kindled the whole battle-line in its neighborhood. Costello describes how the Rifles were keenly skirmishing with the French when "we heard a loud cheering to our left, and beheld the 3rd division charge over a bridge much lower down the stream. Fired with the sight, we instantly dashed over the bridge before us."

Nothing could be more impressive than the spectacle at that moment.

"The passage of the river says Maxwell, "the movement of glittering masses from right to left as far as the eye could range, the deafening roar of cannon, the sustained fusillade of the artillery, made up a magnificent scene. The British cavalry, drawn up to support the columns, seemed a glittering line of golden helmets and sparkling swords in the keen sunshine, which now shone on the scene of battle."

L'Estrange, who was with the 31st, gives one touch of unexpected colour to the scene. The men, he says, were marching through standing corn, yellow for the sickle, and between four and five feet high, and the cannon balls, as they rent their way through the sea of golden grain, made Iong hissing furrows in it.

"In all my military life," says Costello, "this sight surpassed anything I ever saw; the two armies hammering at each other, yet with all the coolness of a field-day exercise, so beautifully were they brought into action."

The hill in front of the village of Arinez was the key of the French line, and Wellington took Picton with the 3rd division in close columns of regiments at a running pace, diagonally across the front of both armies, to attack it, while the heavy cavalry of the British came up at a gallop from the river to sustain the attack. The hill was known as "the Englishmen's hill."

It was the scene of a great fight in the wars of the Black Prince, where Sir William Felton, with 200 archers and swordsmen, being surrounded and attacked by 6000 Spaniards, all perished, and the story of their dogged valour still lives in the legends of the neighbourbood. The fight on this spot was, for a few minutes, of singular fierceness. Fifty French guns covered the hill with their fire, the French infantry clung with furious valour to the villaue.

"The smoke and dust and clamour," says Napier, "the flashing of firearms, the shouts and cries of the combatants, mixed with the thundering of the guns, were terrible." A battalion of Rifles found themselves in front of a long wall, strongly hold by some battalions of French infantry, and the blaze of fire for a moment checked the Rifles.

Running forward, however, they reached the wall, and for a few moments on either side of that unconscious barrier of brickwork was a mass of swaying, shouting, and furious men.

"Any person," says Kincaid, who was one of the Rifles pressing against the wall, "who chose to put his head over from either side, was sure of getting a sword or a bayonet up his nostrils."

In a moment, however, the Rifles broke over the barrier, and the French fell back through the village, carrying their guns with them. The Rifles pushed on eagerly to seize the guns, and one officer, young and swift-footed -- Lieutenant Fitzmaurice -- outran his men, overtook the last French gun, caught the bridle of the leading horse, and tried to pull it to a stop. The French driver leaned over, and fired his pistol at Fitzmaurice's head, but only shot off his cap! Fitzmaurice clung to the horse, and the Rifles coming up, the gun was captured.

L'Estrange describes, with all the vivacity of an eyewitness, the movement which marked the crisis of the fighting at the centre. "I heard a tremendous rush," he says, "on our left; the ground seemed actually to quake under me.; and, looking in the direction of the sound, I saw the whole British host-artillery, cavalry, and infantry-throwing themselves on the line of the French army. Three or four regiments of cavalry were at the moment charging, and galloped up to the foot of the eminence on which the French line stood; it was too steep for the horses to ascend, and they were obliged to wheel. But the firm and uncompromising style in which the British army advanced was too much for the nerves of the French; they turned in retreat along their whole line, and the battle of Vittoria was won."

Duel

Graham, all this time, was waging fierce duel with Reille for the Bayonne road, on which depended the retreat of the French. Robinson, who commanded a brigade of the 5th division, formed his men in three columns and led them forward at the double to carry the bridge and village of Gainara; but the French fire was so furious that the strength of the attack was broken. Robinson rallied his men, took them on again, stormed the village, and even crossed the bridge.

But the French in turn, gallantly led, came back to the fight. Twelve guns concentrated their fire on the British as they tried to deploy when they had crossed the bridge. The French, in a word, held the bridge, the British the village, and neither could prevail over the other. More British troops came up. Again the bridge was carried and again lost; and Reille thus barred the passage of the river till the tumult of Wellington's battle in the centre, sweeping towards Vittoria, shook Reille's constancy. He fell back, and Graham held the Bayonne road.

In the centre the battle had resolved itself into a sort of running fight for six miles, the tuniult and dust of the conflict filling the whole valley, and wakening confused echoes in the bills that looked down upon the scene. At six o'clock the French were 'holding the last ridge a mile in front of Vittoria. "The sim was setting," says Maxwell, " and his last rays fell upon a dreadful spectacle-red masses of infantry were advancing steadily across the plainthe horse-artillery came at a gallop to the front to open its fire upon the fugitives -- the Hussar Brigade was charging by the Camino Real." The French clung with unshaken. gallantry, but with broken and desperate fortunes, to this their last position. Here is Napier's picture of the scene:

"Behind them was the plain in which the city stood, and beyond the city thousands of carriages and animals and non-combatants, men, women, and children, were crowding together in all the madness of terror; and as the English shot went booming overhead, the vast crowd started and swerved with a convulsive movement, while a dull and horrid sound of distress arose; but there was no hope, no stay for army or multitude; it was the wreck of a nation. Still the courage of the French soldier was unquelled. Reille, on whom everything now depended, maintained the Upper Zadora, and the armies of the south and centre, drawing up on their last heights between the villages of Ali and Armentia, made their muskets flash like lightning, while more than eighty pieces of artillery, massed together, pealed with such a horrid uproar that the hills laboured and shook and streamed with fire and smoke, amidst which the dark figures of the French gunners were seen bounding with frantic energy."

Nothing, however, could check the strength of the British attack. The French were driven in confusion through Vittoria; Graham held the road to Bayonne, and Joseph turned his routed and broken troops upon the road to Salvatierra. The new line of retreat led through a marsh; the road was choked with carriages and fugitives; the British guns and cavalry were pressing on in stern pursuit.

The French had to abandon their guns -- they carried off but two pieces out of 150 -- and night fell upon such a scene as earthly battles have not often seen. The roads round Vittoria were strewn with the wreck of three armies, the prodigious booty of plundered Spain; wagons, caissons, timbrels, abandoned guns, carriages filled with weeping women, droves of sheep and oxen, riderless horses.

"It seemed," says an eye-witness, "as if all the domestic animals in the world had been brought to this spot, with all the utensils of husbandry, and all the finery of palaces, mixed up in one heterogeneous mass."

"The plunder," says Alison, "exceeded anything witnessed in modern war. for it was not the produce of the sack of a city or the devastation of a province, but the accumulated plunder of a kingdom during five years."

The military chest of the defeated army contained no less than 5,500,000 dols. This was strewed in glittering coin on the dusty crowded road; while of private wealth the amount was so prodigious that "for miles together the fighting troops may be said to have marched upon gold and silver, without stooping to pick it up."

Joseph himself only escaped capture by jumping out of one door of his carriage as his pursuers reached the other. He left his regalia and his sword of state, however, in the carriage; in it, too, were found a number of most beautiful pictures cut out of their frames and rolled up, the plunder of Spanish convents and palaces. Joseph had a nice taste in art, but was not in the least nice as to how he gratified it.

As to guns, Wellington himself said, "I have taken more guns from these follows than I took at Assaye." Marshal Jourdan's baton of command was found amongst the booty, and sent by Wellington to the Prince Regent, who sent him in acknowledgment an English baton as marshal.

Leith Hay offers us one sudden and curious vision of a defeated army in flight. Late in the day Wellington rode to the summit of a low hill beyond Vittoria, whence, for a mile at least, the wreck of Joseph's army was visible.

"The valley beneath," says Leith Hay, "represented one dense mass, not in column, but extended over the surface of a flat containing several hundred acres. The very scale of the multitude seemed to make motion impossible. Little movement was discernible, and inevitable destruction seemed to await a crowd of not less than 20,000 people."

Ross's troop of horse-artillery was brought hurriedly up, and opened a shell fire on the huge mass, which, with a wave of panic, broke loose in one far-scattering wave of fugitives.

The French, curious to say, suffered comparatively little in the retreat. Lord Hill's biographer says that this was due to the speed with which the French fled. "They ran so fast," he says, "king, marshals, generals, and men, that the allies, who had been sixteen hours under arms, and had marched three leagues since the day dawned, had no chance of overtaking them."

Rearguard Maintained

But this is scarcely just to the French. Their courage was not broken though their fortunes were wrecked, and always a valiant rearguard was maintained. Tomkinson, in his Diary of a Cavalry Officer, has described how the British cavalry rode in again and again upon the French rear-guard.

"I rode up," he says, "within a yard of the enemy's infantry: they had their arms on the port, and were as steady as possible, not a man of them attempting to fire till we began to retire. They certainly might have reached myself and many others with their bayonets had they been allowed. I never saw men more steady and exact to the word of command."

The truth is, that the efficiency of the British pursuit was greatly hindered by the vastness of the plunder which fell into the hands of the British soldiers. Intemperance broke out amongst the troops; the bonds of discipline were for the moment relaxed. In the actual battle only some 5000 men were killed and wounded, but three weeks after the battle above 12,000 soldiers had temporarily disappeared from their colours.

Napoleon's wrath at the disaster of Vittoria may be imagined. He writes from Dresden on July 3, 1813: "It is hard to imagine anything so inconceivable as what is now going on in Spain. The king could have collected 100,000 picked men; they might have beaten the whole of England."

A week later he writes from Wittenberg: "I have ordered the Minister of War to suspend Marshal Jourdan, to send him to his country residence, and keep him there till he has explained what has happened."

He is bitterly angry that his Minister of War has expended a few compliments on the unhappy Joseph.

"When a man's inept folly has ruined you," he wrote on July 11, 1813, "I may, indeed, show him sufficient consideration not to take the public into my confidence, but it is hardly an occasion on which to pay him compliments."

He bids his Minister tell Joseph that "his behaviour has never ceased bringing misfortune on my army for the last five years. It is time to make an end of it. There was a world of folly and cowardice in the whole business."

The army in Spain, he said later, had a general too little and a king too much.

But while Napoleon thus tore his hair in private on the subject of Vittoria, he sent round a circular to all his Ministers to guide their utterances as to Spanish affairs. The French armies, they were to say, "were making certain changes in their positions, and a somewhat brisk engagement with the English took place at Vittoria, in which both sides lost equally. The French armies, however, carried out the movements in which they were engaged, but the enemy seized about 100 guns which were left without teams at Vittoria, and it is these that the English are trying to pass off as artillery captured on the battlefield!"

To resolve Vittoria into "a somewhat brisk engagement," and one in which "both sides lost equally," is, even for Napoleon, a quite heroic feat of lying! "As for the newspapers," Napoleon writes to Clark on August 1, 1813, "nothing must be said either of the Vittoria business or of the king."

Wellington, it will be remembered, ranked Vittoria as one of his three greatest victories. It revealed to the world his real scale as a general. Napier sums up the results of the battle in his own resonant and stately sentences: "Joseph's reign was over; the crown had fallen from his head. And, after years of toils and combats, which had been rather admired than understood, the English general, emerging from the chaos of the Peninsula struggle, stood on the summit of the Pyrenees a recognised conqueror. From these lofty pinnacles the clangour of his trumpets pealed clear and loud, and the splendour of his genius appeared as a flaming beacon to warring nations."

It is a touch, perhaps, of bathes, but it has all the effect of humour, to read of the condition in which the unfortunate Joseph emerged from the battle. "King Joseph," writes Larpent in his " Journal " the morning after the battle, "had neither a knife and fork nor a clean shirt with him last night."

With Vittoria, indeed, Joseph practically vanishes from history. Two years afterwards he landed at New York disguised under the plebeian title of Monsieur Bouchard, and he settled down into the peaceful repose of a New Jersey farm, where, if he had less splendour than at Madrid, he had fewer agitations. He was offered the crown of Mexico, but, with a brilliant flash of common sense, be refused it, with the remark that he had worn two crowns and would not run the risk of trying a third.

Chapter XXIX: San Sebastian and the Pyrenees

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com