On July 1, with the exception of the garrisons of

Pampeluna and San Sebastian, and Suchet's sorely shaken

forces on the east coast, not a French soldier remained in Spain.

On July 1, with the exception of the garrisons of

Pampeluna and San Sebastian, and Suchet's sorely shaken

forces on the east coast, not a French soldier remained in Spain.

Jumbo Map of San Sebastian Attack (very slow: 284K)

Three great armies had practically vanished like wreaths of wind-blown mist. Clausel, with 18,000 men, had narrowly escaped capture. He had fallen back upon Saragossa, making a forced march of sixty miles in forty hours, and thence found his way through a difficult hill-pass into France, leaving most of his artillery and baggage behind him.

Graham had pushed Foy and his division out of Irun and across the Bidassoa, the stream which marks the boundary of Spain. But the French still held the two great fortresses of Pampeluna and San Sebastian. Wellington knew Pampeluna to be badly provisioned, and he established a strict blockade upon it, trusting to the slow logic of hunger to compel its surrender.

But San Sebastian needed sterner and swifter treatment. It was a port in daily communication with France, and Wellington could not advance through the Pyrenees, leaving San Sebastian like a thorn in his flank. It was a third.rate fortress, ill-armed, and believed to be imperfectly garrisoned.

Fortune, however, had given San Sebastian a commander with a genius for defence surpassing even that of Philippon at Badajos. Emmanuel Rey was in command of a great convoy moving towards France when the thunderclap of Vittoria shook French power in Spain into ruins. Rey sent on his convoy, threw himself into San Sebastian, and set himself, with soldierly promptitude, and infinite art and energy, to prepare for the great siege which he knew to be inevitable.

And, thanks to his stubborn daring and exhaustless resource, the last syllables in the record of the Peninsular war shine, for the French, with a sort of baleful and splendid fame. Rey, it may be added, was something of a Falstaff -- a French Falstaff -- in personal appearance. Fraser, who was second in command of the British artillery in the siege, describes him as "a great fat man, heavy- bodied and moon-faced." But that he possessed, in an almost unique degree, the qualities for holding a fiercely besieged post is amply proved by the bloody tale of San Sebastian.

Of all the famous sieges of the Peninsula, that of San Sebastian is the most tragical and dramatic; and in that fierce siege the fighting in the Pyrenees forms a sort of parenthesis, making up a little patch of battle landscape, strangely vivid and murderous, set, as in a sort of framework, in the smoke and flame of a great siege.

Imposing Position

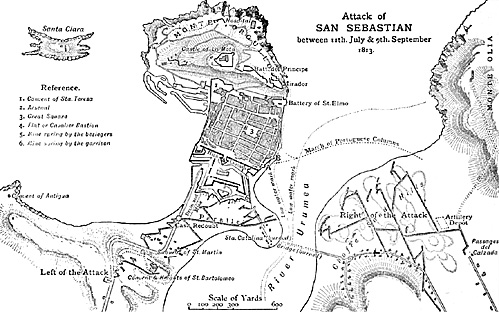

Just where the rugged shoulder of the Pyrenees looks down on the stormy waters of the Bay of Biscay, a curving sandy peninsula juts out into the sea. At its narrowest part it is only some 350 yards wide. The shallow, tidal channel of the river Urumea defines the eastern edge of the isthmus. The tip of the isthmus curves to the west; on its extremity rises a steep rocky hill named Monte Orgullo, some 400 feet high, crowned by a castle. The defences of the town consisted of the heavily armed castle on Monte Orgullo; a solid curtainjutting out into a huge horn-work at its centre which crossed the neck of the isthmus; and a convent which had been turned into a strong post of defence, and stood some 600 yards in advance of the curtain.

A line of ramparts running along the eastern face of the isthmus connected the castle, on the north of the town, with the curtain to the south. The garrison consisted of some 3000 men. The town itself, later in the siege, was turned into a tangle of street defences, suggested, perhaps, by painful French experiences in Saragossa. And certainly the French defended San Sebastian with a courage as high and stern, if not quite as fanatical, as that with which the Spaniards made the story of Saragossa immortal.

French courage, it may be added, needs a gleam of hope, if not a thrill of flattered vanity, to make it perfect, and these useful ingredients were very happily supplied to the garrison throughout the siege. They were in daily communication with France, and so complete was their command of sea transit to the opposite French shore, that Trafalgar might well have been a French, instead of an English victory, and not England, but France have been mistress of the sea.

The British Admiralty gave Wellington no help. His transports were captured almost daily by French privateers, and boats came every night from Bayonne to San Sebastian, bringing reinforcements, supplies, and aid of a more imaginative kind-carefully medicated news; frantic exhortations to courage ; crosses, decorations, and promotions for the soldiers who distinguished themselves in the fighting each day. Above all, the open sea and the daily talk with Bayonne gave the French garrison in San Sebastian a constant sense, not only of imminent succour, but of certain and easy retreat.

Graham, with 10,000 men, had charge of the siege. His engineers adopted the plan of attack which had been followed by Berwick when besieging San Sebastian in 17ig. They planted their batteries on the sandhills beyond the Urumea, and breached the eastern wall connecting the curtain with the castle. Simultaneously an attack was opened along the front of the curtain itself.

A gallant, but furious and unwise, haste marked the earlier stages of the siege. Graham had youthful and fiery spirits about him, fretting to reach French soil, and keen to employ against what seemed the feeble defences of San Sebastian the wild valour that had been shown on the great breach at Badajos.

The breaching batteries thundered tirelessly across the stream of the Urumea, each gun averaging 350 rounds in a little over fifteen hours; a torrent of flame in which the guns themselves seemed to melt almost faster than the wall beyond the river crumbled beneath the tempest of flying iron hurled upon it. The guns against the great convent in advance of the curtain got into action on their own account even earlier than the breaching batteries ; and on July 17 the convent was stormed with fiery daring, and turned into an advanced battery against the curtain. On July 23, two breaches had been made in the eastern wall, and it was determined to attack.

The forlorn hope consisted of twenty men of the 9th and of the Royal Scots, under Colin Campbell, afterwards famous as Lord Clyde. Fraser was to lead a battalion of the Royal Scots against the great breach; the 38th was to leap on the smaller and more distant breach - the 9th was in support; the whole making an attacking force Of 2000 men. Wellington had given orders that the assault should be delivered in fair daylight, but, by some blunder, the signal to advance was given while darkness still lay black on the ithmus, and so the batteries beyond the river could not aid the assault.

The men broke out of the trenches, and at a stumbling run and with disordered ranks, pressed over the slippery, weed-clad rocks towards the breach. The French ' from the high eastern wall, under whose face the storming column was defiling, smote the British attack cruelly with their fire. Only some 300 yards had to be passed, but even in that brief space the slaughter was great.

Halt

The leading files of the British halted, and commenced to fire at what seemed a gap in the wall, and which they mistook for the breach. That check at the head of the rush brought the whole column to a confused semi-halt, and along its entire extent, from the high parapets above them poured a rain of musketry shot. Men fell fast. The confusion was great. Some of the officers broke out of the crowd, raced forward to the true breach, and pushed gallantly up its rough slope.

On reaching its summit they saw before them a black gulf from twenty to thirty feet deep. Beyond it, in a curve of fire, ran a wall of blazing houses. On each flank the breach was deeply retrenched; from the front, and from either side, there rained on the British stormers a tempest of missiles.

Nothing could surpass the daring of the British leaders. Fraser, who led the Royal Scots, leaped from the crest of the breach into the black gulf beyond, and died there. Officer after officer broke out of the crowd, and, with a shout, led a disconnected fragment of the storming party up the breach, only to perish on the crest. The river was fast rising, it would soon reach the foot of the wall. The attacking force, with leaders slain, order broken, and scourged by a bewildering fire from every quarter, to which it could make scarcely any reply, fell sullenly back into the trenches. But thick along the base of the wall, and all up the slope of the great breach, splashing the broken grey of its surface with irregular patches of scarlet, lay the dead red-coated English.

That gallant but ill-fated rush, unhappy in all its incidents, cost the British a loss of nearly 600 men and officers. In the twenty days the siege had now lasted the total loss had reached 1300.

At this point there breaks in on the siege the bloody parenthesis of the fighting in the Pyrenees. Napoleon realised that what his armies in Spain needed most of all was a general. Fraternal affection, at any time, went for little with Napoleon; and with Wellington threatening to break in on French soil through the Pyrenees, the French emperor was not disposed to deal too tenderly with a brother who was guilty of the crime of failure. On July 1 an imperial decree was issued, superseding the unfortunate Joseph, and appointing Soult to the command of the army in Spain. That limping, club-footed soldier, now Massena had vanished from the stage, possessed the best military head at Napoleon's command, and he amply justified

Napoleon's confidence. Perhaps his zeal was pricked into new energy from the fact that his long quarrel with Joseph had ended in a personal triumph. Soult had, as a matter of fact, express authority to arrest the unhappy Joseph if he proved inconveniently obstinate.

On July 13 Soult reached Bayonne, and his quick brain, tireless industry, and genius for organisation, wove the shattered fragments of three defeated armies, with the speed of magic, into a great force of 80,000 strong, and he promptly formed the plan for an aggressive campaign, on a daring scale, in the Pyrenees. That campaign lasted only nine days; but it included ten stubborn and bloody engagements, was marked by some of the most desperate fighting in the whole course of the war, and involved a loss of 20,000 men.

On July 25 Soult put his columns in motion, first publishing an address to his soldiers of the true Napoleonic type, and announcing that a proclamation of victory would be issued from Vittoria itself on Napoleon's birthday, not three weeks distant. This was an audacious prophecy, which left out of reckoning Wellington and his army.

As a matter of fact, when Napoleon's birthday arrived, Soult, with his strategy wrecked and his army defeated, was emerging breathless and disordered from the Pyrenees on French soil again.

Pyrenees Overview

It is impossible to give an account, at once detailed and intelligible, of the fighting in the Pyrenees. The scene of operations was so tangled and wild, with peaks running up to the snows, and valleys sinking down into almost impassable gulfs, that only a model of the country in relief could make it intelligible to the reader.

The barest outline of the operations is all that can be attempted here. The scene of the contest is, roughly, a parallelogram of mountains, its eastern face, some sixty miles long, stretching from Bayonne to St. Jean Pied de Porte, along which runs the river Nive -- its western line stretches from San Sebastian to Pampeluna. These four places, at the angles of this hilly trapezoid, were held by the French; the siege against San Sebastian was being fiercely urged, and Pampeluna was sternly blockaded. Soult had to choose betwixt attempting the relief of one or other of these places. He believed Pampeluna to be in the greater danger, and resolved to march to its help.

If there be pictured some Titanic hand laid diagonally on this table of mountains, the wrist in front of Pampeluna, the knuckles of the hand forming the crest of the range, and the outstretched fingers -- pointing towards Bayonne, but not reaching it -- forming the hills and passes which look towards France -- a rough conception of the scene of the fighting will be had. Soult had one great advantage over the Enylish.

On the level ground beyond these mountainous "finger-tips," where the passes sank to the plain, he could move his columns quickly, and pour them suddenly and in overwhelming strength into any pass he chose. Wellington's divisions, on the other hand, scattered along the summits of the hills running down towards France, were parted from each other by deep intervening valleys.

It was quite possible, therefore, that Soult could throw his force with almost irresistible strength into a given pass, break through Wellington's line, raise the blockade of Pampeluna, and take Wellington's positions one after another in flank. Wellington had to cover the siege of two fortresses, parted from each other by sixty miles of mountains; and it would take him a day longer to concentrate on his right for the defence of Pampeluna than to call back his divisions round San Sebastian. This was another reason which led Soult to strike at the force holding Pampeluna blockaded.

French Counterattack

With fine generalship he fixed Wellington's attention at the other extremity of his front by throwing bridges across the Bidassoa. Then, having tricked even Wellington's hawk-like vision, on July 25 he suddenly poured his strength into the passes of Maya and Roncesvalles.

D'Erlon, with 20,000 troops, took the British by surprise in the pass of Maya. Napier, indeed, denies that the British were caught off their guard. "At least if the general was surprised," he says, "his troops were not." Stewart, who was in command, was a hardy soldier, but not a great general; and Henry, in his Recollections of Military Life says, "To my certain knowledge, everybody in Maya was taken by surprise."

Stewart had bidden his troops cook their dinner, and himself had gone back to Orizondo, when, at half-past eleven, the French columns were suddenly discovered coming swiftly up the steep ravine.

The British were flung into the light in fragments, and as their regimental officers could bring them on. It was a battle of 4000 men, brought irrevularlv and in sections into action, against four times their number, and with the advantage 'in favour of the larger force both of surprise and of regular formation. Never was there fighting fiercer or more gallant.

The men of the. 82nd fought with stones when their ammunition failed. "The stern valour of the 92nd, principally composed of Irishmen," says Napier, "would have graced Thermopylae."

The 92nd would no doubt have fought just as magnificently if its ranks had been filled from Galway or from Kent, but, as the regimental roll shows, in its ranks were 825 Highlanders and only 61 Irishmen. Barnes' brigade, brought late in the day into the fight, checked the advance of the French with stern resolution, but by nightfall the British had lost i 5co men and ten miles of the pass.

Soult himself, with 35,000 men, led the attack on the pass of Roncesvalles. Byng stood in his path, posted on crags rising hundreds of feet in the air; but he had only 5000 men, of whom more than half were Spanish. Byng was assailed by 18,000 French in front, while another column moved past his flank. Cole came up to Byng's support; and Ross, a fine soldier, with only three companies of the 20th and one of a German regiment, ran in upon the French column engaged in the flanking movement, and by sheer audacity arrested its advance.

But the French were not to be denied. They pushed past the British flank, and at nightfall Cole, who was now in command, fell back, and the French gained the ridge. Pampeluna was only twenty-two miles distant. The next day, July 26, the British were still falling back, but a bewildering fog lay on the hills and filled the valleys with its blinding vapour. Soult was waiting to hear of D'Erlon's success in the pass of Maya; and his characteristic defect as a general -- the lack of overpowering fighting energy -- made him hesitate. He failed to strike hard at the retiring British; and as Picton was pressing up to join Cole, that hesitation robbed Soult of his best chance of success.

On the morning of the 27th Picton and Cole were in front of Huarte, still covering Pampeluna. D'Erlon and Soult, in a word, had carried both passes, but they had failed to push resolutely on, down the reverse of the range, to Pampeluna, before the British could come up in force to bar the road.

On the night of the 25th Wellington heard of Soult's advance. He instantly converted the siege of San Sebastian into a blockade, and rode to the scene of action, calling up his scattered forces as he rode. The 3rd and 4th divisions were in position at Sauroren when Wellington arrived.

The two armies confronted each other from either side of the deep valley. Wellington had despatched his last aide-de-camp with an order to the troops in his rear, and rode alone on to the British position, halting on the shoulder of a hill where he was easily seen. A Portuguese battalion near saw him, and raised an exultant shout, which ran, a gust of stormy sound, along the curve of the British hill.

As it happened, Soult, with his staff, was at that moment on the opposite slope, and so deep was the valley, and so near the opposite hill, that the two leaders could distinguish each other's features. Looking at his formidable opponent, Wellington said, as if speaking unconsciously, "Yonder is a great commander, but he is cautious, and will delay his attack to ascertain the cause of these cheers. That will give time for the 6th division to come up, and I shall beat him."

Fatal Hesitation

That is exactly what happened. Soult hesitated. He failed to throw his whole strength into the fight till the next day. By that time the 6th division had come up, and Soult was defeated.

On the 28th Soult tried again to break through the British line, and the fight is known as the first battle of Sauroren. Wellington himself described the fight as "fair bludgeon-work;" Napier says "it was a terrible battle."

A French column, issuing from the village of Sauroren, moved straight up the hill, and in a fashion very unusual with the Frenchin perfect silence, that is, and without firing a shot. The speed and power of its charge remained unabated in spite of a tempest of lead poured on it. A Portuguese regiment in its path was shattered as with a thunderbolt, and the crest was won!

Then Ross's brigade, with a loud shout, closed on the column in a fiery charge, and in turn flung it down the hill. But other columns of attack, as resolute and fierce as the first, were by this time flecking the whole hillside. It was an army of 25,000 attacking one of 12,000.

At one point the assault was four times renewed, and, says Napier, "the French officers were seen to pull up their tired men by the belts, so fierce and resolute were they to win." But win they could not.

"Every regiment," says Wellington, "charged with the bayonet, and the 40th, the 7th, the 20th, and the 23rd four different times." When night fell, nearly 2600 men had fallen on the British side, but they still kept the hill!

On the 29th the exhausted armies remained sullenly watching each other. Then Soult, with the adroitness of a good soldier, changed his tactics. He could not reach Pampoluna, but by moving at speed to his right, he could leap on Hill, and break through to reach San Sebastian. Reille was to hold the position in front of Wellington, and Soult, gathering up D'Erlon with 18,000 men, marched at speed against Hill.

D'Erlon fell on Hill on July 30. He had 20,000 against Hill's 10,000. Hill fought stubbornly, and, finding that his left was being turned, fell back to a still stronger position in his rear, the loss being heavy on both sides. But meanwhile Wellington had penetrated Soult's plan, and instantly attacked Reille, who had been left in his front. Soult believed Reille's position impregnable; and so it might have proved to a general less adroit and troops less daring. Picton was thrust past the French left, the 2nd division turned their right; Inglis, with, 500 men of the 7th division, carrying, by a desperate charge, the hill which formed the extremity of the French position. Byng, with his brigade, carried the village and bridge of Sauroren, and the French, attacked both in flank and front, were broken and driven back in great confusion. The British lost 1500 men in this fight, the French more than 2000, with 3000 prisoners.

Soult had thus failed in his leap on Pampeluna and on San Sebastian in turn; nothing was left now for him but to escape back to France. He marched all through the night of the 30th across the Donna Maria pass, and it became a neck and neck race with his pursuers, who were keen to cut him off. Twice he escaped by the narrowest interval of time.

The Light Division, under Victor Alten, marched forty miles in nineteen hours to reach a narrow bridge spanning a defile at Yanzi, which the French must cross. The British reached the edge of a cliff which overlooked the bridge just as the French, pushing on at utmost speed, and carrying their wounded, were crossing it. "We overlooked the enemy at a stone's throw, and at the summit of a tremendous precipice," says an officer who was an eye- witness of the scene. The British opened an almost vertical fire on the bridge, and the scene which followed was wild and tragical. The main body of the French escaped, but their baggage and many prisoners fell into the hands of the British.

On August 2 the British held almost exactly the same position as when Soult commenced his movements. Napoleon's best lieutenant, in a word, had failed, and French troops, fighting with a courage worthy of Arcola or of Eylau, had yet been driven, a wrecked army, with more than one-fourth their number slain or captured, in wild retreat out of the passes they had entered only ten days before with so much military pride. Then Wellington resumed his siege of San Sebastian.

Chapter XXX: The Storming of San Sebastian

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com