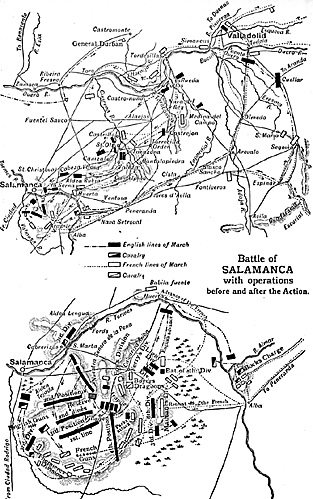

North of Salamanca the Tormes forms a great

loop, and on the night of July 20 Marmont had seized the

ford of Huerta at the crown of the loop. He could march

down either bank of the river to Salamanca. Wellington was

in front of Salamanca, in a position perpendicular to the

river, his left opposite the ford of Santa Maria, his

right-thrust far out into the plain-touched, but did not occupy,

one of a pair of rocky and isolated hills called the Arapiles.

North of Salamanca the Tormes forms a great

loop, and on the night of July 20 Marmont had seized the

ford of Huerta at the crown of the loop. He could march

down either bank of the river to Salamanca. Wellington was

in front of Salamanca, in a position perpendicular to the

river, his left opposite the ford of Santa Maria, his

right-thrust far out into the plain-touched, but did not occupy,

one of a pair of rocky and isolated hills called the Arapiles.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Salamanca (very slow: 294K)

He thus stood in readiness for battle on the left bank of the river betwixt Marmont and Salamanca. On the right bank of that stream, opposite the ford of Santa Maria, was the 3rd division, strongly entrenched.

From these positions the wearied armies confronted each other for nearly two days; but on July 23 Marmont's reinforcements would be up, and Wellington decided he must retreat. This was exactly what Marmont feared, and he watched with feverish alertness for every sign that the British were falling back. On the 22nd the Frenchman made a daring move. He marched straight down from the crown of the river-loop, seized the outer of the two hills we have described, and made a dash at the inner one. If he could seize both he would hold an almost unassailable position within easy striking distance of his enemy.

Wellington, however, quickly sent forward some troops to seize and hold the nearer Arapiles. The race was keen. The French reached the hill first, but were driven from it by the more stubborn British. These rugged hills, rising suddenly from the floor of the plain, were not quite 500 yards apart: and in an instant they were thus turned into armed and menacing outposts, from whose rough slopes two great armies, within striking distance of each other, kept stern watch.

Marmont could use the hill he held as a pivot round which he might swing his army, so as to cut the English off from the Ciudad Rodrigo road. Wellington, to guard against this, wheeled his lines round-using the English Arapiles as a hingethrough a wide segment of a circle, till his battleline looked eastward, and what had been his rear became his front.

The English Arapiles, and not the ford of Santa Maria, thus became the tip of his left wing; his right, thrust out to the village of Aldea Tejada, barred the road by which Marmont might slip past to Salamanca. For hours the two armies stood in this position. Wellington's baggage and wagons meanwhile were falling back along the road to Ciudad Rodrigo, and their dust, rising in the clear summer air, caught Marmont's troubled eye. Wellington, he believed, was in retreat, and would escape!

At that thought Marmont's prudence vanished. He hurried his left wing-two divisions with fifty guns, under Maucime-at speed along the crest of some low hills that ran in a wide curve round Wellington's position. Maucune was to seize the Ciudad Rodrigo road, and so throw Wellington off his only line of retreat. But, in his eagerness to reach that prize, Marmont forgot that he was dislocating, so to speak, his own left wing.

As Maucune moved away, a gap, growing ever wider, yawned in the French front. And it was almost as perilous to commit such a blunder in Wellington's presence as in that of Napoleon himself. Wellington watched with cool content till Marmont's blunder was past remedy.

"At last I have him," broke from his lips; and, turning to the Spanish general, Alava, who stood by his side, he caught him by the arm, and said, "My dear Alava, Marmont is lost!" Then he sealed Marmont's fault, and made it irretrievable, with a counter-stroke of thunder. The 3rd division was shot across the head of Maucune's columns, the 5th was hurled upon its flank.

Pakenham was in command of "the Fighting Third," and Wellington's orders were given to him in person, and with unconventional bluntness. "Do you see those fellows on the hill, Pakenham?" he said, pointing to where the French columns were now visible; "throw your division into columns of battalions at them directly, and drive them to the devil!"

Pakenham, an alert and fiery soldier, formed his battalions into column with a word, and took them swiftly forward in an attack described by admiring onlookers as "the most spirited and most perfect thing of the kind ever seen."

His columns, as they neared the French, deployed into line, the companies bringing forward their right shoulders at a run as they marched, and the astonished French, who expected to see an army in retreat, suddenly found these red, threatening lines, edged with deadly steel, moving fiercely on them.

The French broke into a hurried fire, their columns tried to deploy, their officers sacrificing themselves to win them space and time. But the advance of the 3rd was as unpausing and relentless as fate. As they neared the French the more eager spirits began to run forward: the lines seemed to curve outward, and Pakenham, in his own words "let the men loose." The bayonets fell to the level, the English ran in with a shout, and the French formation was shattered almost in an instant.

Wallace's brigade, to quote the description of an eye- witness, halted a moment as they reached the brow of the hill to dress their lines, disordered by the speed of their advance and the heavy fire of the French guns. Just as they paused, Foy's column throw in a deep and rolling volley, and in a moment the earth was strewn with fallen soldiers from Wallace's front. Stepping coolly over their slain or wounded comrades, however, the brigade moved steadily forward; and Wallace, leading them, turned, looked back on his own men, and with an inspiring gesture pointed to the enemy. That gesture was the signal to charge!

French Reverse

The French themselves believed that, having caught their enemies with a fire so dreadful, they had destroyed them, and were now moving forward in triumph, when they saw through the smoke the faces of their opponents coming on with bayonets at the charge. In an instant there came from the British a prolonged and shattering volley, followed without a moment's pause by the fierce push of the bayonet. The solid French column swayed backwards, crumbled into fragments, and fled!

In this fight the 44th captured the eagle of the French 62nd, while two standards were taken by the 4th and 3oth, The regimental record of the 44th says that the French officer who carried the eagle wrenched it from the pole, and was endeavouring to conceal it under his grey overcoat, when Lieutenant Pearce attacked him.

A French infantry soldier came up with levelled bayonet, but was shot dead by a private of the 44th. The eagle was captured, fastened to a sergeant's halberd, the 44th giving three cheers, and was carried in triumph through the whole fight, gleaming above English bayonets instead of French.

Close following on Pakenham's charge came a splendid exploit on the part of the British cavalry. The French light horse rode at the right flank of Pakenham's division. At a single word of command the 5th fell back at an angle to the line, and one farheard volley drove the French horse off with broken squadrons. The 5th division was by this time pressing heavily on Maucune's flank. Suddenly the interval betwixt the two British divisions was filled with the tumult of galloping hoofs.

The Heavy Brigade -- the 3rd and 4th Dragoons and the 5th Dragoon Guards -- under Le Marchant, and Anson's light cavalry, were riding at speed on the unhappy French. Three massive bodies of ranked infantry in succession were struck and destroyed in that furious charge, and the leading squadron, under Lord Edward Somerset, galloping in advance, caught a battery of five guns, slew its gunners, and brought back the guns in triumph. Many of the broken French infantry fled to the English lines for protection from the long swords of the terrible horsemen.

That fiery, exultant rush of British horsemen completed the destruction of Maucune's division, and captured no less than 2000 prisoners.

In the last charge the three regiments had become mixed together; the officers rode where they could find places, but a rough formation was kept; and still riding at speed, the English horsemen drove at the French. At ten yards' distance the French threw in a close and murderous volley which brought down nearly every fourth horse or man. But the rush of galloping horsemen was not checked, and in a moment cavalry and infantry were joined in one mad mwlwe.

At last the French broke and fled. Le Marchant himself rode and fought like a private soldier in the charge. When the French broke he drew rein and commenced to call back his dragoons. He saw a considerable mass of French infantry draw together, and a handful of the 4th Dragoons prepare to charge them. He joined the little band of cavalry, and with brandished sword rode at their head and fell, shot through the body, under the very bayonets of the French.

It was five o'clock when the battle began - before six o'clock the French left was destroyed. This is the fact which made a French officer describe Salamanca as " the battle in which 40,000 men were beaten in forty minutes." But the battle was not quite over yet. Marmont, riding in fierce despair to where the fight was raging, eager to remedy his blunder, had fallen desperately wounded, and been carried off the field. Bonnet, his successor, too was wounded; the command fell into the hands of Clausel, a cool and resourceful soldier.

At one point only the British attack had failed. Pack's Portuguese brigade had been launched at the French Arapiles. But the advantage of ground was with the French. By some blunder the Portuguese were led against a shoulder of the hill alinost as steep as a house-roof. "The attack," says Sir Scott Lillie, "was made at the point where I could not ascend on horseback in the morning."

The French met the Portuguese, too, with a sort of furious contempt, and drove them back. in wreck-, and, for a moment, the British line at this point was shaken. Wellington in person brought up Clinton's division, and the French, grown suddenly exultant and coining on eagerly, were driven back.

Night was now falling on the battlefield, but the long grass, parched with the summer heat, had caught fire, and night itself was made luminous with the racing flames as they ran up the hill-slopes and over the level, where the wounded lay thick. Clausel, with stubborn courage and fine skill, was covering the tumult of the French retreat, while Clinton was pressing on him with fiery energy.

Here is Napier's picture of the last scene in this great fight. "In the darkness of the night the fire showed from afar how the battle went. On the English side a, sheet of flame was seen, sometimes advancing with an even front, sometimes pricking forth in spear-heads, now falling back in waving lines, anon darting upwards in one vast pyramid, the apex of which often approached yet never gained the actual summit of the mountain; but the French musketry rapid as lightning sparkled along the brow of the height with unvarying fulness, and with what destructive effects the dark gaps and changing shapes of the adverse fire showed too plainly; meanwhile Pakenham turned the left, Foy glided into the forest, the crest of the ridge became black and silent, and the whole French army vanished as it were in the darkness."

Spanish Blunder

The French were saved from utter destruction by a characteristic Spanish blunder. They could pass the Tormes at only one of two points -- Alba de Tormes, where Wellington had placed a strong Spanish force, and Huerta.

Wellington, riding with the foremost files, reached Huerta, and found it silent and empty. The French had gone by Alba de Tormes, which the Spanish general in charge had carelessly abandoned.

"The French would all have been taken," wrote Wellington afterwards, "if Don Carlos had left the garrison in Alba do Tormes as I directed, or if, having taken it away, he had informed me it was not there." As it was, the French found the ford open, and pushed their retreat with such speed, that, on the day after the fight, Clausel was forty miles from Salamanca.

Wellington overtook the French rear-guard on the 23rd, and there followed a memorable cavalry exploit, one of those rare instances in which steady squares have been crushed by a cavalry charge.

The heavy German horse, riding fast with narrow front up a valley, found the French in solid squares of infantry on the slope above them. The left squadron wheeled without breaking their stride, and rode gallantly at the nearest square. The French stood firm and shot fast, but the Germans charged to the very bayonet points. A wounded horse stumbled forward on the face of the square, and broke it, and in a moment the horsemen were through the gap, and the square was destroyed. A second square and a third were in like manner shattered. These fine horsemen, that is, in one splendid charge destroyed three infantry squares and captured 1400 prisoners! Wellington described this charge as "the most gallant he ever witnessed."

Salamanca was a notable fight and an overwhelming victory. Wellington himself would have selected Salamanca as the battle which best proved his military genius. If not so history-making as Waterloo, or so wonderful, considered as a mere stroke of war, as Assaye, it was the most soldierly and skilful of all Wellington's battles. He certainly showed in that fight all the qualities of a consummate captain-keen vision, swift resolve, perfect mastery of tactics, the faculty for smiting at the supreme moment with overwhelming strength-all in the highest degree.

In numbers the French were slightly superior; in artillery their superiority was great. Marmont's army was made up of war-hardened veterans, in that mood in which the French soldiers are most dangerous, the exultant expectation of victory. Yet in little more than an hour that great, disciplined, exultant host, with leaders slain and order wrecked, was rolling in all the tumult and confusion of defeat along the road which led to Alba do Tormes.

With some justice Wellington himself said, "I never saw an army receive such a beating." It reached the ford a mob rather than an army. All regimental formation had vanished. The men bad lost their officers, officers had forgotten their men, soldiers had flung away their arms. The single purpose of the disordered multitude was flight. Salamanca certainly proves that Wellington knew how to strike with terrific force!

The British lost in killed and wounded 5200; the French loss was 14,000, of whom 7000 were prisoners. Three French generals were killed, four were wounded, two eagles, six standards, and eleven guns were captured. Three weeks after Salamanca Clausel could gather at Valladolid less than one half of the gallant host smitten with disaster so sudden and overwhelming on the evening of July 22.

The news of this great defeat reached Napoleon in the depths of Russia on September 2, and the tidings filled him with wrath. He declared that the unhappy Marmont had "sacrificed his country to personal vanity," and was guilty of "a crime." Failure, indeed, was, in Napoleon's ethics, the last and worst of crimes, the sin that had never forgiveness. Napoleon's rage against Marmont, curiously enough, was only soothed by the perusal of Wellington's despatches describing the battle. Napoleon himself had turned the manufacture of bulletins into mere experiments in lying, and he knew that all his generals followed his example.

He never, therefore, believed the accounts given by his generals of their operations. But when he read Wellington's despatch he said, "This is true! I am sure this is a true account; and Marmont, after all, is not so much to blame."

Far-Reaching Victory

The effect of the victory in Spain was far-reaching and instant. Joseph fell back in haste towards Madrid. Soult had to abandon the siege of Cadiz, surrender the fertile plains of Andalusia, and sullenly gather his columns together for retreat northwards. Wellington himself marched on Madrid. The moral effect of driving Joseph from his capital must be immense, and decided the English general's tactics.

On the night of August 11, Joseph abandoned the city, on the 12th Wellington entered it, amid a tumult of popular rejoicing. On the 13th the Retiro, with its garrison, over 2000 strong, surrendered. It was the chief arsenal yet remaining to the French in Spain, and contained 180 guns and vast military stores. It shows Joseph's feeble generalship that he left such a prize to the English.

Wellington now seemed at the height alike of fame and of success. In a single brief campaign he had captured two great fortresses, overthrown a powerful army, an army commanded by a famous French marshal; he had driven Joseph in flight to Toledo, and had occupied Madrid in triumph. But in reality Wellington's position was most perilous, and the peril grew every hour more menacing. Soult was marching from Andalusia; from every province the French columns were gathering towards Valencia. If the armies of Soult, Joseph, and Suchet united, they would form a host thrice as great in scale as that under Wellington's command.

An expedition from Sicily, indeed, under Lord Bentinck, was to have landed at Alicante, on the eastern coast of Spain, so as to hold Suchet engaged, and make a combination so dangerous impossible. But Bentinck chose to attempt a meaningless adventure in Italy instead, and the English Cabinet lacked energy sufficient to compel him to carry out the plan arranged.

Bentinck took 15,000 good soldiers into Italy, where he accomplished nothing. Thrown into the east of Spain, he might have changed the course of history. "Lord William's decision," wrote Wellington, "is fatal to the campaign, at least at present. If he should land anywhere in Italy, he will, as usual, be obliged to re-embark, and we shall have lost a golden opportunity here."

Wellington, however, calculated on outstripping the French armies in speed, and beating them if met in equal numbers, or evading a battle if their numbers were overwhelming, until, by discord amongst the commanders and hunger in the ranks, the French hosts were driven once more asunder.

Chapter XXVI: Climax and Anti-Claimax

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com