Meanwhile Burgos was the next great place of strength

the French held in the north, and Wellington resolved to

assail it. It commanded the French line of communications

with the Pyrenees. Its capture would enable Wellington to

cut himself loose from Lisbon as a base, and to find a new

sea base on the northern coast. On September 1 Wellington

left Madrid, Clausel falling back before him; on the 19th

he reached Burgos. The castle of Burgos stood on the

summit of an oblong conical hill, close to the base of

which flows the Arlanzon.

Meanwhile Burgos was the next great place of strength

the French held in the north, and Wellington resolved to

assail it. It commanded the French line of communications

with the Pyrenees. Its capture would enable Wellington to

cut himself loose from Lisbon as a base, and to find a new

sea base on the northern coast. On September 1 Wellington

left Madrid, Clausel falling back before him; on the 19th

he reached Burgos. The castle of Burgos stood on the

summit of an oblong conical hill, close to the base of

which flows the Arlanzon.

Jumbo Map of Siege of Burgos (very slow: 261K)

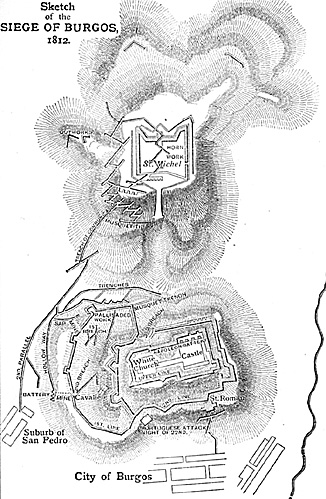

There were three concentric lines of defences. The first, running round the base of the hill, consisted of an old esearp wall, modernised and strengthened. Next, higher up the slope, came a complete field retrenchment, palisaded and formidably armed. Higher still came another girdle of earthworks. There are two crests to the hill; on one stood an ancient building called the White Church, which had been transfigured into a modern fortress; on the second and higher crest stood the ancient keep of the castle, turned by the skill of the French engineers into a heavy casemented work called the Napoleon battery.

The fire of the Napoleon battery commanded all the lower lines of defence save to the north, where the slope was so sharp that the guns of the castle could not be depressed sufficiently to cover them. Three hundred yards from this face rose the hill of San Michael, held by a powerful hornwork, the front scarp of which, hard, slippery, and steep-angled, rose to a height of twenty-five feet, and was covered by a counter-scarp ton feet deep. Wellington's plan was to carry by storm the hornwork on San Michael, thence by sap and escalade to break through the successive girdles of defence, and storm the castle.

Napier gays that Burgos was "a small fortress, strong in nothing but the skill and bravery of its defenders." Jones, who took part as an engineer in the attack, says that it "would only rank as a very insignificant fortress when opposed to the efforts of a good army."

And yet Burgos represents one of Wellington's rare failures. The siege was pushed for thirty-three days, five assaults were delivered, the besiegers suffered a loss of more than 2000 men, and then the siege was abandoned!

What can explain such a failure?

In part, no doubt, the failure was due to the skill and courage with which the place was defended. Dubreton, its commander, was a soldier of a very fine type. He had all Philippon's genius for defence, and added to it a fiery valour in attack to which Philippon had no claims. In the siege of Burgos the sallies were almost as numerous -- and quite as fierce -- as the assaults.

Lord Londonderry, however, gives the key to the story when he says that the castle of Burgos "was a place of commanding altitude, and, considering the process adopted for its reduction, one of prodigious strength." It was the disproportion betwixt the means of attack and the resource for defence which explains the failure of the siege.

Wellington, in a word, was attempting to pull down Burgos, so to speak, with the naked hand. His siege train consisted of three 18-pounders and five howitzers. There was not even, as Jones puts it, a half-instructed miner or a half-instructed sapper to carry out operations. For the few guns employed by the besiegers there were not enough balls, and a sum of money was paid for every French shot that could be picked up and brought to the batteries. Probably, every second ball fired at Burgos was in this way a French derelict discharged at its original owners.

On the evening of October 6, Jones records "there remained only forty-two rounds of 24-pounder shot." The siege must have stopped from sheer lack of ammunition, but that the batteries were able to fire back at the French the bullets which the French had already discharged at them.

As Jones sums up the story of the siege: "The artillery was never able to make head against the fire of the place; the engineers, for want of the necessary assistance, were unable to advance the trenches; and the garrison were hourly destroying the troops without being molested themselves."

And yet this siege without guns and without engineers, a mere effort of almost unarmed valour, would have succeeded but for the advance of the French armies for its relief. A great prize was thus missed. In Burgos lay the artillery and stores of the whole army of Portugal. Its capture would have left the French without the power to undertake a siege anywhere.

The plan of the siege was to carry by sap, or mines, or escalade, rather than by gun-fire, each of the lines in succession, turning the guns of the captured line against the one next to be attacked. Even with such inadequate appliances Burgos ought to have offered no unconquerable difficulty to the troops that had stormed Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos.

But, for one thing, Wellington did not employ in the siege the soldiers who had performed those feats. The attacking force at Burgos consisted of Portuguese troops and of the ist and 6th divisions, composed chiefly of young or sickly troops. Wellington himself said afterwards that his fault at Burgos was that "I took there the most inexperienced instead of the best troops." It may be added that time was a decisive element in the siege. Souham, with 30,000 troops, hovered near, only waiting for reinforcements to come up to fall on Wellington; while Soult, moving from Andalusia, threatened his communications with Portugal.

Wellington's first stop was to assault the great hornwork on San Michael. It was a skilfully constructed work, with a sloping scarp 45 feet high, heavily armed and covered by the fire of the castle. The assault was delivered on the night of September ig; the resistance was desperate. At one point the assault failed, and the British lost more than 400 men. But the 79th, led by Major Somers Cocks, broke in, and the place was carried, the garrison fighting its way through and escaping.

On the night of September 22 an attempt was made to escalade, the exterior line of works, and it failed. The wall was 23 feet high; the Portuguese who shared in the attack hung back. The British escalading party, made up of detachments from the 79th and the Guards, raced up their ladders bravely, but were in numbers quite inadequate to their task.

They were driven back with great loss, and their leader, Major Lawrie of the 79th, was left dead in the ramparts. Lawrie shone in pluck, but failed in conduct. As Wellington put it, "He paid no attention to his orders, notwithstanding the pains I took in writing and reading and explaining them to him twice over. Instead of regulating the attack as he ought, he rushed on as if he had been the leader of a forlorn hope. He had my instructions in his pocket; and, as the French got possession of his body and were made acquainted with the plan, the attack could never be repeated."

A mine was next driven under the ramparts and exploded on the 29th, and an imperfect breach formed. A party of the 1st division tried to storm it, and failed. Part of the storming party missed the breach in the dark, found the wall uninjured, and returned, reporting no breach existed. A sergeant and four men, however, found the true breach, mounted its crest, the defenders falling back in panic. The men of Badajos, they believed, were upon them.

Discovering at last that the attacking party consisted of only five soldiers, the French rallied, drove their assailants down the breach, and the brave sergeant and his comrades returned with streaming wounds, to tell of their failure.

On October 4 another mine was exploded, a new breach effected, and a party of the 24th, under Lieutenant Holmes, instantly charged through the smoke, scrambled over the ruins of the breach, and gained the parapet. The old breach at the same moment was assaulted by another detachment under Frazer, and so swift was Frazer's leading, and so gallantly was he supported, that this breach too -- though strongly guarded -- was carried.

Sortie

On the next evening, however, a strong party of French leaped from the upper line of defence, charged down with great speed and resolution, caught the English unawares, drove them out, and destroyed the lodgment they had made. Only with great slaughter was the position re-won.

On the night of the 7th, again, the French made a daring sortie, in repelling which there fell one of the finest soldiers in the army, Major Somers Cocks.

On the 11th another mine was sprung, a breach formed, and the outer line carried. On the 18th a desperate attempt was made to carry the second line by escalade. The attack was gallant, and for a moment success seemed won. Then, in overpowering numbers, the French rallied, and drove back their assailants.

The siege of Burgos, as we have said, was really an attempt to pull down stone walls, gallantly held and formidably armed, with the naked hand. Yet, in spite of the many failures of the siege, Wellington would undoubtedly have captured Burgos but that the army of the north had by this time reinforced Souham.

Soult had effected a junction with the army of the centre under Jourdan, and Wellington ran the imminent risk of being assailed by forces nearly treble his own. On October 21 the siege was raised. In the darkness of night the British army filed under the walls of the castle, and crossed the bridge of the Arlanzon, which lay directly beneath the guns of Burgos. The wheels of the English artillery were bound with straw, orders were given only in whispers, and, noiselessly almost as an army of ghosts, the troops crossed the bridge.

Some Spanish horse, however, found that silent march so close to the frowning guns of Burgos too trying for their nerves. They broke into a gallop; the sound of their hoofs woke the castle. The guns opened fire but in the darkness soon lost their range, and did little harm.

Then began that tragical retreat from Burgos to Ciudad Rodrigo, a chapter of war written in characters almost as black as those which tell the story of the retreat to Corunna. The retreat lasted from the night of October 21, when Wellington's troops defiled in silence across the bridge under the guns of Burgos, to November 20, when, ragged, footsore, with discipline shaken and fame diminished, and having lost 9000 men killed, wounded, or "missing," it went into cantonments around Ciudad Rodrigo.

In its earlier stages the retreat had, so to speak, two branches. Wellington was falling back in a southerly line from Burgos to Salamanca; Hill was retreating before Soult westwards from Madrid to the same point. After a junction was effected the combined army fell back from Salamanca to Ciudad Rodrigo. The course of the famous retreat may be thus compared roughly to the letter Y, with Burgos and Madrid representing the tips of the extended arms, Salamanca as the point of junction, and Ciudad Rodrigo the base. The whole route of Wellington's troops, by the road they traversed from Burgos to Ciudad Rodrigo, is less. than 300 miles; the time occupied in traversing it was nearly five weeks.

The marches were short, the halts long. And yet the British army came perilously near the point of mere dissolution in the process.

The secret of the sufferings and losses of the march may be told in half-a-dozen sentences. The weather was bitter; the rain fell incessantly; the rivers ran bank-high. The route lay through marshy plains with a clayey subsoil. The troops toiled on "ankledeep in clay, mid-leg in water," oftentimes barefooted, till strength failed. The British commissariat broke hopelessly down. For days the troops fed on acorns and chestnuts, or on such wild swine as they could shoot.

Many of Wellington's troops had marched from Cadiz; many were survivors from the Walcheren expedition, with the poison of its bitter fever yet in their blood. So sickness raged amongst them. Wellington's staff worked badly. There was no accurate timing of the marches.

A regiment would stand in mud and rain, knapsack on back, for hours, waiting for some combination that failed.

The retreat, too, was marked by a curious succession of tactical mischances to the English. Souham was pushing Wellington back always by a flanking movement round his left; and river after river was lost by the accident of a mine failing or of a bridge being neglected. Twice in this campaign, it must be remembered - - after the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo and of Badajos, that is -- the British troops had got completely out of hand, and had plunged into furious license. This had shaken the authority of the officers and loosened the discipline of the men. And in this way the excesses of Ciudad Rodrigo and of BadaJos helped to produce the disorder and horrors of the retreat from Burgos. The British soldier in retreat is usually in a mood of sullen disgust, which makes him a difficult, if not a dangerous, subject to handle.

At Torquemara were huge wine-vaults, and the British rear-guard fell on these with a thirst and recklessness which turned whole regiments for the moment into packs of reeling and helpless drunkards. It is said that 12,000 British soldiers were at the same moment in a state of sottish drunkenness. This might have led to some startling disaster but for the circumstance that the pursuing French army got slightly more drunk than even the English. Under such conditions it is not to be wondered at that the disastrous siege of Burgos, and the yet more disastrous retreat from it, cost Wellington 9000 men.

Wellington's difficulties, it is to be noted were created by his very success. When he seized the capital and marched on Burgos, he was thrusting at the very heart of the French power, and this produced a hurried concentration of the French armies from every part of Spain. This was the political and strategic result for which Wellington made his stroke. He brought up Soult from Andalusia, Caffrelli from the north, Suchet from Catalonia, and so delivered these provinces. But the military result was a concentration before which, since his stroke at Burgos had failed, he had to fall back.

In the retreat curious terms were established betwixt the pursuing French cavalry and the files of the British rear- guard. The effervescence of battle betwixt them had vanished, there remained only its flat and exhausted residuum. They exchanged jests as well as sword-strokes and bayonet-thrusts. The French horsemen would ride beside the heavily-tramping British infantry "sometimes almost mixing in our ranks," as an officer who was present writes, or near enough to bandy wit in had Spanish.

Every now and again the French horse would make a sudden charge; there would be a chorus of shouts, a crackle of angry musketry. A score of stragglers would be carried off, a dozen slain or wounded would be stretched on the muddy road, but the retreat never paused.

Costello, in his Adventures of a Soldier, gives many details of the sufferings of the rank and file as they trudged along the muddy roads, most of them barefoot, or halted it night under the pelting showers without fire or food.

The officers suffered equally with the men. Costello draws a touching picture of one gallant youth, Lord Charles Spencer, only eighteen years of age, during one of the halts. The gallant lad was faint with hunger, trembling with cold and weakness. "He stood perched upon some branches that had been cut down for fuel, the tears silently running down his cheeks for very weakness. He was waiting while a few acorns were roasted, his only meal. More than one rough soldier brought from his knapsack some broken fragment of biscuit and offered it to the exhausted youth. In such scenes as those supplied by the retreat," says Costello "lords find that they are men, and men that they are comrades."

Retreat

The retreat was marked by some brilliant strokes of soldiership on both sides. At Venta del Pozo Halket's Germans and the 11th and 16th Dragoons, in a gallant sword-fight, drove back a mass of French horsemen much stronger than themselves in number. The Douro was turned by the French with a feat of daring rare even in this war. A regiment of the German brigade had destroyed the bridge at Tordesillas, and held in strength a tower at some little distance from the site of the ruined bridge.

In the bitter winter night sixty French officers and sergeants, headed by an officer famous for his exploits, named Guingret, made a small raft, on which they placed their clothes, and, each man carrying his sword in his teeth, swam across the turbid and icecold river, pushing their raft before them. On reaching the farther bank they raced, naked as they were, at the tower and carried it. The spectacle of sixty naked Frenchmen, sword in hand, suddenly emerging from the river and the darkness, and charging furiously at them, was too much for the astonished Germans! The tower was abandoned, and the passage of the French across the river secured.

Junction

At Salamanca the junction of Hill raised Wellington's forces to 50,000 British and Portuguese troops, with 12,000 raw Spaniards. But Souham's columns had joined those of Soult, the latter being in command of the whole. The French had thus a host of 90,000 veteran soldiers, 12,000 being cavalry, and 120 guns. Wellington held both the Arapiles, and offered battle. The ground was classic, and Wellington hoped he might repeat on Soult the stroke which had destroyed Marmont.

Soult, as a matter of fact, repeated Marmont's fatal turning movement past Wellington's right, striking at the British communications. But he was less rash than Marmont, and Wellington's terrible smiting power was better understood. So Soult moved slowly round the English right in a wide curve beyond the reach of attack. But the curve was too wide.

"Marmont," says Napier, "closing with a short, quick turn, a falcon striking at an eagle, received a buffet that broke his pinions and spoilt his flight. Soult, a wary kite, sailing slowly and with a wide wheel to seize a helpless prey, lost it altogether." Wellington, watching Soult's movement, throw his army rapidly into three columns, crossed the Junguen, and, in order of battle, with his artillery and cavalry disposed as a screen, marched his whole force round the French left, and reached the Valmusa, beyond the curve of Soult's sweep. That astonished commander at nightfall found the adroit Englishman outside his columns! Wellington held the main road, while the French were floundering along the country tracks. A low-lying fog and blinding rain-showers made the landscape obscure -- but Wellington had achieved the feat of carrying his army across the front of the largest French force ever gathered in one mass in the Peninsula, an army having two guns for every one the English possessed, and with 12,000 of the finest cavalry in the world.

The French suffered almost as much in pursuit as the English in retreat, and the mere failure of means of subsistence made it impossible for them to hold their forces together for many days. Soult's great army broke up, and the memorable campaign of 1812 ended.

Wellington issued a circular-letter to the commanding officers of battalions rebuking in bitter sentences the disorders which arose in the retreat from Burgos. "The officers," he declared, "had lost all command of their men," and this was due to their "habitual inattention to their duty."

"Discipline," he wrote, "had suffered in a greater degree than he had ever witnessed, or even read of, in any army; and this without the excuse of special hardships."

"No army," he said, "had ever made shorter marches in retreat, had longer rests, or been so little pressed by a pursuing enemy."

In that famous memorandum Wellington lost his usual cool judgment and clear vision of facts. The army had suffered more than he knew; perhaps more than he cared to know.

"At one time," says the regimental record of the 44th, "the men were without biscuit for eleven days, and received only one small ration of beef." As showing the losses in the retreat, a sergeant of the 7th company came up to his captain and reported, "Sir, the mule and campkettles are lost; but as I am the only man of the company left, it is not of much consequence."

Wellington's censures, too, lacked discrimination. Some regiments -- notably the Light Division and the Guards -- had borne themselves like good soldiers in the retreat. But Wellington's chief defect in dealing with his soldiers lay in lack of sympathy, and a too ready indulgence in cold and sword-edged censure.

That a campaign which began with the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo and of Badajos, and included the triumph of Salamanca and the entrance into Madrid, should have ended in the retreat from Burgos seems such an anti- climax as can be scarcely paralleled in history. It was a profound disappointment to English public opinion, and brought on Wellington himself a tempest of angry criticism. For a time the real scale of the marvellous success Wellington had achieved was obscured. Yet, as Wellington himself, who always talked in sober prose, claimed, it was the most successful campaign in which a British army had for a century been engaged. Wellington had never more than 60,000 effective soldiers under his command -- the French had more than four times that force. But Wellington had captured the two great frontier fortresses, overthrown Marmont, entered Madrid in triumph, delivered the whole south of Spain, captured the French arsenals in Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajos, Salamanca, Madrid, Astorga; taking -- if Seville and the lines before Cadiz be included -- no less than 3000 guns, and he had sent 20,000 French soldiers as prisoners to England.

And all this, it is to be noted, had been done practically without any help from the Spanish armies. That Hill, indeed, had to fall back from Madrid was owing to the deliberate disloyalty of the Spanish general Ballesteros, a betrayal which even the Spanish Junta found it necessary to punish by dismissal and imprisonment. Had Wellington, indeed, captured Burgos, there lay before him a very glittering possibility. Marching forward, and gathering up the forces of Ballesteros and the troops from Alicante, he would have confronted Soult with 100,000 men, and have inflicted upon him a defeat more shattering than that Marmont suffered at Salamanca -- a defeat that might well have driven the French from Spain.

This would have been the natural and shining climax of the campaign of 1812. The disloyalty of Spanish generals, the blunders of the Spanish Junta, and the utter failure of co-operation and help from Spain generally, spoiled this great scheme and gave to history the anti-climax of Burgos.

Chapter XXVII: A Great Mountain March

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com