The power of Napoleon may be said to have reached its highest point at the beginning of 1812. He had shattered in turn every combination of the Great Powers of Europe; he had entered in succession almost every European capital as a conqueror. The mere recital of his victories has sound like the roll of drums. Russia and Austria had joined with England in the effort to check his masterful rule in 1805; Russia and Prussia in 1806 Austria and Spain in 1809. But all was vain. Coalitions crumbled like houses of cards at the touch of Napoleon's sword. He made and unmade kings at pleasure. He rearranged empires to suit his ambition.

"All Europe's bound-lines," to quote Mr Browning, were "drawn afresh in blood" at his will.

A map of Central Europe in 1812 shows the Napoleonic France stretched from the North Sea, the Adriatic, from Brest to Rome, from Bayonne to Lubeck. The 85 departments of France had grown to 130. Rome, Cologne, and Hamburg were French cities, and a girdle of dependent States almost doubled the actual area of the French Empire. Napoleon himself was king of Italy; Murat, his brother-in-law, the son of an innkeeper, was king of Naples; Joseph was king of Spain; Louis, of Holland. The Confederation of the Rhine, the Helvetic Republic, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, were but idle titles that served as labels for fragments of the empire of Napoleon. England, Russia, Turkey, and Scandinavia alone escaped his sway. But Russia was his ally and accomplices Turkey and Scandinavia were mere dishes waiting to be devoured. There remained, in fact, only England -- proud, solitary, unsubdued!

And yet 1812 is the year which marks the beginning of Napoleon's downfall -- downfall swifter and more wonderful than even his amazing rise. When Massena drew sullenly back from the lines of Torres Vedras, it was the ripple which marks the turn of an ocean-tide. French conquests had reached their farthest limits, and 1812 brought the two movements which, combined, overthrow Napoleon. It brought the war with Russia and the advance into Spain of Wellington.

Three days after Wellington crossed the Agueda on his march to Salamanca -- the victory which was to shake French power in Spain to its very base -- Napoleon crossed the Niemen in that fatal march to Moscow which was within six months to wreck his reputation, destroy. his whole military strength, and shake his throne to its fall.

Wellington's advance into Spain marked an essential change in the character of the Spanish struggle. It was no longer a defensive war, maintained by an unknown general against troops and marshals confident of victory. It was a war in which, at last, emerges a captain whose fame was to rival that of Napoleon, and whose strategy was to drive the soldiers and generals of France in hopeless ruin out of Spain.

The pride of Napoleon himself never soared higher than at the opening of the war with Russia. He was beginning, he dreamed, a campaign which would overwhelm all his enemies in one vast and final defeat.

"Spain," said Napoleon to Fouche, "will fall when 1 have annihilated the English influence at St. Petersburg. I have 800,000 men, and to one who has such an army Europe is but an old prostitute who must obey his pleasure. . . . I must make one nation out of all the European States, and Paris must be the capital of the world."

The war, in a word, was but "the last act in the drama" the great drama of his career. It is interesting to learn that, in his own judgment, Napoleon was thus aiming at London when he began his march to Moscow; and he so misread facts as to believe he was overthrowing Spain when routing Cossacks beyond the Niemen.

As a matter of fact, Napoleon was committing the blunder which was to cost him his crown.

When his many columns crossed the Niemen in June, they seemed a force which, in scale of discipline and equipment, with Napoleon for captain, might well conquer the world. Five months afterwards, a handful of ragged, frost-bitten, hungerwasted fugitives, flying before the Cossack spears, they recrossed the Niemen.

The greateest army the world had seen had perished in that brief interval! In his Moscow campaign Napoleon was contending not so much with human foes as with the hostile forces of nature. His army perished in a mad duel with frost and ice and tempest, with hunger and cold and fatigue. Not the sharpness of Cossack spears or the stubborn courage of Russian squares overthrew Napoleon; but the cold breath of the frozen North, the far-stretching wastes of white snow, across which, faint with hunger, his broken columns stumbled in dying thousands.

But there were two fields of battle -- Spain and Russia -- and the war with Russia gave Wellington his opportunity in Spain. Napoleon starved his forces in that country to swell his Russian host. In 1811 there were 372,000 French troops with 52,000 horses in Spain. But in December 1811, 17,000 men of the Imperial Guard were withdrawn.

By the beginning of 18 12 some 60,000 veterans had marched back through the Pyrenees, and their places were taken by mere conscripts. Some of the best French generals, too, were summoned to the side of Napoleon, and Wellington found himself Confronted by leaders whose soldiership was inferior to his own.

So 1812 marks the development of a new type of war on the part of the great English captain. He had, it is true, difficulties sufficient to wreck the courage of an ordinary general, and he had still to taste of great disasters. His troops were ill fed, ill clad, and wasted with sickness. Their pay was three months in arrears. The horses of his cavalry were dying of hunger. He had not quite 55,000 men, including Portuguese, fit for service. He was supported by a weak and timid Cabinet in England. His Spanish allies were worthless. Human speech has hardly resources sufficient to describe the follies and the treacheries of the assemblies which pretended to govern Spain and Portugal.

Yet, under these conditions, and with such forces and allies, Wellington framed a subtle and daring plan for seizing the two great frontier fortresses, Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos, and for beginning an audaciouslv aggressive campaign against the French in Spain.

Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos stand north and south of the Tagus, which flows equidistant betwixt them. If we imagine an irregular triangle, of which Lisbon is the apex; one side running due west 120 miles long, reaches to Badajos; another side running north-west for 180 miles stretches to Ciudad Rodrigo; the base from Ciudad Rodrigo to Badajos is 100 miles. It is plain that Lisbon is easily threatened from both these fortresses, and both were held by the French. To make Lisbon safe, and to make an advance into Spain possible, both must be captured. Yet the feat seemed impossible.

Wellington had scarcely any battering train. Marmont, with an army of 65,000, was almost within sound of the guns of Ciudad Rodrigo. The least sign of movement towards Badajos would fetch Soult up from Andalusia in overpowering strength. The problem for the English general was to snatch two great fortresses, strongly held, from under the very hand of two mighty armies, each equal to his own in strength.

This was the feat which by foresight, audacity, and the nicest calculation of time, Wellington accomplished. His preparations were so profoundly hidden that they remained unsuspected. Hill was, of all Wellington's commanders exactly the one who, when detached, kept all French generals within fifty miles of him on the alert; and by keeping Hill in movement on the Guadiana, Wellington fixed French attention on that quarter. Marmont was lulled into drowsy security. His columns were scattered over a wide area; the scene of action seemed to lie in the west. Ciudad Rodrigo was apparently forgotten by both sides. Then suddenly Wellington, to borrow Napier's words, "jumped with both feet on the devoted fortress!"

Ciudad Rodrigo

Ciudad Rodrigo

Ciudad Rodrigo was the great frontier plac d'armes for the French. The siege equipage and stores of two armies lay in it. It was strongly held, under a very able commander, Barre; but its best defence lay in the certainty that Marmont would instantly advance to its succour. But Wellington calculated that it would take twenty-four days for Marmont in full force to appear for the relief of the place, and within that period he reckoned Ciudad Rodrigo could be carried. But the siege must be fierce, vehement, audacious, Wellington, as a matter of fact, outran even his own arithmetic. He captured Ciudad Rodrigo in twelve days.

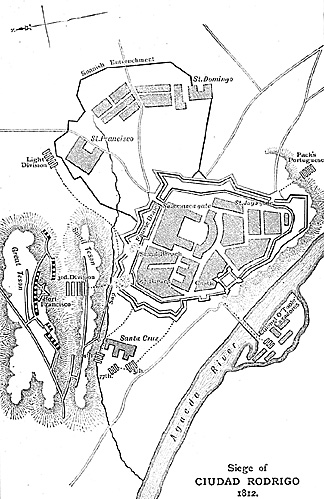

Jumbo Map of Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo (very slow: 254K)

The feature of the famous siege is the swift succession, the unfaltering certainty of each stroke in it. Never before was a besieged city smitten with strokes so furious, and following one another with such breathless speed.

In shape Ciudad Rodrigo roughly resembles a triangle with the angles truncated. At the base of the triangle runs the Agueda, making a vast and flowing ditch along the south-western front. Opposite the northern angle are parallel rocky ridges, called the Upper and the Lower Teson. The upper and farther ridge was within 600 yards of the city ramparts; the lower and nearer Teson was only 180 yards distant, and was crowned by a powerful redoubt called Francisco. The nights were black, the weather bitter; the snow lay thick on the rocky soil, the river was edged with ice, and the bitter winter gales scuffled wildly over the ramparts of Ciudad Rodrigo. So wild was the weather that Picton himself, the hardiest of men, says of the day when the troops approached the city, "It was the most miserable day I ever witnessed: a continuous snowstorm, the severity of which was so intense that several men of the division perished of cold and fatigue."

"The garrison," says Kincaid, " did not seem to think we were in earnest; for a number of their officers came out under the shelter of a stone wall within half musket-shot, and amused themselves in saluting and bowing to us in ridicule." Before next morning. some of these very officers were British prisoners!

The 1st, 3rd, and Light Divisions formed the attacking force, but they had to encamp beyond the Agueda, and to ford that river, crisp and granulated with ice, every time they marched into the trenches, where the men remained on duty for twenty-four hours in succession. Wellington attacked from the two Tesons.

He broke ground on the night of January 8, and the same night stormed the redoubt on the Lower Teson. Colborne led six companies from the Light Division to the assault. The men went forward at a run. Part swept round the redoubt and hewed their way through the gate; part raced up the glacis and scrambled over the counterscarp. They found the palisades to be within three feet of it, promptly used their fascines to improvise a bridge, walked over the palisades, reached the top of the parapet, and swept the defenders away. The redoubt was carried in twenty minutes!

The gate, as it happened, was burst open by a French shell. A sergeant was in the act of throwing it on the heads of the English when he was shot. The shell, with fuse alight, dropped from his hand amongst the feet of some of the garrison: they kicked it energetically away. It rolled towards the gate, exploded, shattered the gate with its explosion, and instantly the British stormed in. Never was a French shell more useful to English plans!

Ten days of desperate artillery duel followed, the batteries from the trenches crushing the walls with their stroke, while fifty great guns from the walls roared back into the trenches, and the sound, rolling in far-heard, dying echoes along the hill summits, suggested that the distant mountains, says Napier, were mourning over the doomed city. Sir Charles Stewart in a letter describes the scene when the breaching batteries opened their fire.

"The evening chanced to be remarkably beautiful and still. There was not a cloud in the sky, nor a breath of wind astir, when suddenly the roar of artillery broke in upon its calmness, and volumes of smoke rose slowly from our batteries. These, floating gently towards the town, soon enveloped the lower parts of the hill, and even the ramparts and bastions, in a dense veil; whilst the towers and summits, lifting their heads above the haze, showed like fairy buildings, or those unsubstantial castles which are sometimes seen in the clouds on a summer day. The flashes from our guns were answered promptly from the artillery in the place, the roar of their thunder, reverberating among the remote mountains of the Sierra de Francisca, with the rattle of the balls against the masonry, and the occasional crash as portions of the wall gave way."

On January 19 two breaches were practicable, and Wellington, sitting on the reverse of one of the advanced approaches, wrote the orders for the attack. Those pencilled sentences, written to the sullen accompaniment of the bellowing cannon, sealed the fate of Ciudad Rodrigo.

The main breach was to be assaulted by Picton's division, "the Fighting Third." Mackinnon led one brigade, Campbell the other. The light companies of the division, under Major Manners of the 74th, were the storming party. Mackie of the 88th led the forlorn hope. The Light Division was to attack the smaller breach, George Napier leading a storming party of 300 men, Gurwood a forlorn hope of twenty-five men. The light company of the 83rd, with some Portuguese troops, was to attack an outwork in front of the castle, so as to destroy the fire of two guns which swept the breach; Pack, with a Portuguese brigade, was to make a feigned attack on the gate of St. Jago.

From the great breach, 100 feet wide, ran a steep incline of rugged stones. It was strewn with bombs and hand-grenades; two guns swept it with grape; a great mine pierced it beneath. It was a mere rugged pathway of death.

The winter night closed in early. Darkness lay on Ciudad Rodrigo like a pall. The British trenches were silent. The fortress rose massive and frowning in the gloom, the breaches showing like shadows cast on its wall. A gun was to give the signal for the attack, but the men waiting for its sound grew impatient.

A sudden shout broke out on the right of the English attack. It was accepted as the signal, and ran, a tumult of exultant sound, along the zigzag .of the trenches. The stormers for the great breach leaped out; the columns followed hard on them. The black face of the fortress broke into darting flames, and in a moment the air was filled with the tumult of the assault.

The rush at the great breach may be first followed. Picton's men "were quick and fierce in their onfall. The stormers, in a rush which lasted a few breathless instants, reached the ditch, and, with a shout, they leapt into its black depths. The men, on each other's shoulders, or on the hastily-erected ladders, clambered up the farther face, and raced up 'the rough slope of the breach towards where, in the darkness, a bar of darting musketry fire showed, and guarded, the gap in the ramparts.

As the men scrambled over the broken stones, these seemed t, burst into flame under their tread. The exploding hand grenades pricked the rough slope with darting fire points. But nothing could stop the rush of th British. They reached the breach, they swept up as the French were thrust fiercely back. They clung for a few moments with fiery courage to the retrenchments which barred the head of the breach: two French guns, worked with frantic energy, poured blasts of grape, at pistol-shot distance, into the swaying masses of the storming column.

With desperate effort the attacking party at last broke through. But at that moment the mine under the breach was exploded, and Mackinnon with his fore most stormers were instantly slain. Yet the reckless soldiers swarmed up again, and the fight swayed backward and forward as the attack or the defence in turn seemed to prevail.

According to one account, the attack at the great breach broke through just as the men who had carried the smaller breaches came up and took it., defenders in flank. Mackie, who led the forlorr hope of the 3rd division, struggled through the melee up the crest of the breach, leaped from the rampart into the town, and there discovered that the trench which isolated the breach was cut clear through the wall.

He climbed up to the breach again, forced his way through the tumult and the fire, gathered a cluster of men, led them through the deep trench as through a ditch, and was thus the first man who reached the streets of the town from the main breach. The appearance of his group of redcoats in the streets, the men of the Light Division coming up at the same moment, made the French yield the breach.

When the summit of the breach was gained, it was found to be so deeply entrenched that, to quote Jones, the stormers "had to jump down a wall 16 feet in depth, at the foot of which had been ranged a variety of impediments, such as iron crows' feet, iron chevaux-de-frise, iron spikes fixed vertically, the whole being encircled with the means of maintaining a barrier of burning combustibles."

The parapet was gapped with two lateral trenches. They were ten feet deep and ten feet wide, but, by accident, a plank the besieged had used for the purpose of crossing one of these trenches was left, with one end at the bottom of the ditch, the other resting on the lip of the trench next to the breach. This was promptly dragged up, thrust across the trench, and used as a bridge.

Across the second trench the stormers also found a single plank left, and Campbell led the rush over it. While he was on the plank a French officer calling on his men to fire, sprang forward, and made a lunge at Campbell. Campbell parried, and in a moment was across the ditch. So swift, so fierce was the impetus of the attack that, to quote the words of an actor in the strife, "Five minutes had not elapsed from the regiments quitting the shade of the convent wall before a lodgment was made in the town, and the majority of the garrison had thrown down their arms- many never having had time to take them."

At the smaller breach a fight us gallant was raging. Wellington was in the act of giving his final instructions to George Napier, who was to lead the storming party of the Light Division against this breach, when the men Of the 3rd, anticipating the signal, leaped out, and the assault on the great breach began in the manner described. Napier has left a graphic record of the doings of that night. He had been allowed to select his own storming party, and, halting the three regiments which formed the Light Division, as they were on their way to relieve the trenches, he called for 100 volunteers from each regiment.

The entire division instantly stepped forward, and the trouble was to select 300 stormers out of 1500 soldiers, all claiming that perilous honour. Napier himself, with an odd premonition of what would happen, arranged with a surgical friend to be on hand during the assault for the purpose of amputating his arm, as~ he was sure he would lose it; a service which was duly rendeied. With cool judgment Napier forbade his men to load; they must win the breach with the bayonet.

While Wellington himself was pointing out the breach to Napier, a staff officer discovered the unloaded condition of the muskets in the storming party, and demanded "Why don't you make your men load?"

"If we don't do the business with the bayonet without firing," answered Napier, we shall not do it at all; so I shall not load and, says Napier, "I heard Wellington, who was close by, say, 'Let him alone; let him go his own way.'"

Napier believed in silence as well as in steel. He sternly forbade his men to shout, and swiftly, but without a sound, the stormers of the Light Division doubled forward. The ditch, 300 yards distant, was reached, and, in spite of its depth and blackness, crossed without a pause. The stormers clambered up its farther face, and raced up the breach, the French firing fast on them.

A grape-shot smashed Napier's arm, whirling his body round with the impact of the blow, and he fell. At the fall of their leader the stormers stopped for a moment, lifted their muskets, forgetting they were empty, towards the gap above, and then came the sound of 300 muskets all idly snapped at once.

"Push on with the bayonet, men!" shouted Napier. The men broke into a deep-voiced hurrah, ran forward again, their front narrowed to a couple of files. They had to climb, with stumbling feet, to the very muzzles of the steadily-firing French; but nothing could stop the men of the Light Division. A 24-pounder was placed across the actual gap in the ramparts to bar it; but the stormers leaped over it, the column followed. The 13th, according to orders, wheeled to the right, so as to take the defenders of the great breach, where the fight was still raging, in flank, the 52nd cleared the ramparts to the left, and Ciudad Rodrigo was won, the governor surrendering his sword to the youthful lieutenant who led the stormers of the Light Division.

Then followed wild scenes. The men were mad with the passion of the fight and the exultation of victory. There was keen hatred of the Spanish in the British ranks. They had not forgotten the sufferings of the Talavera campaign, and how their wounded were allowed to starve to death, or were abandoned to the French by the Spaniards after that battle. Ciudad Rodrigo was practically sacked by British soldiers, for the moment broken loose from all restraint, and these excesses blacken the fame of the great siege.

The capture of Ciudad Rodrigo cost Wellington nearly 1300 men, and officers, of whom one half fell on the breaches on the night of the assault. Craufurd, the stern and famous leader of the Light Division, was struck down at the head of his men. The storming-party stood formed under the wall, and Craufurd, who led them in person, turned, faced the cluster of desperate spirits he was to lead, and spoke a few words to them.

His voice had always a singular carrying note; but on this occasion the men noticed an unusual depth and range in its tones. He was speaking his last words! "Now, lads, for the breach!" he added, and moved quickly forward. Craufurd himself, with unfaltering step, advanced straight to the crest of the glacis; then, turning, with his keen high voice he shouted instructions to the shot-tormented column of the stormers. He himself stood, a solitary figure, the centre of a furious storm of musketry fire. From the rampart, almost within touch, a double rank of French infantry was shooting fiercely and fast.

Presently a bullet struck Craufurd on the side, tore through his lungs and lodged near the spine. It was a mortal wound, and, as his aide-de-camp, Shaw Kennedy, stooped over him, the dying soldier charged him with a last message to his wife. He was quite sure, she was to be told, that they would meet in heaven!

He was buried in the breach his men had carrieda fitting sepulchre for so stern a soldier.

Gleio, has left a striking picture of the scene at Craufurd's funeral. His body was borne by six sergeants of the Light Division, with Wellington, Beresford, and a cluster of general officers as mourners. The coffin was carried up the rugged breach itself, a rough grave having been dug in its stony heart for the gallant soldier who died upon it. When the coffin was laid on the edge of this strange grave, Gleig says that he saw the tears running down the stern faces of the rugged veterans of the Light Division as they stood in silent ranks around.

Craufurd had his limitations as a soldier. He was stern, fierce, passionate, and of a valour which always scorned, and sometimes fatally violated, prudence. It is of Craufurd's obstinate valour in the fight -- a valour that made him so fiercely reluctant to fall back in the presence of any odds -- that a familiar story is told. Wellington, when Craufurd at last came up, said, "I am glad to see you safe, Craufurd."

"Oh," responded Craufurd coolly, "I was in no danger, I assure you."

"But I was from your conduct," replied Wellington.

Upon which Craufurd observed in an audible aside, "He is damned crusty today!"

It was Craufurd again -- not Picton -- who told a remiss commissary that if provisions for his regiment were not up in time he would hang him! The aggrieved commissary complained to Wellington.

"Did General Craufurd go as far as that?" asked Wellington, "did he actually say he would hang you?"

"Yes, my lord, he did," replied the almost tearful commissary.

"Then," was Wellington's unexpected comment, "I should strongly advise you to get the rations ready; for if General Craufurd said he would hang you, by God he will do it!"

Mackinnon, who commanded a brigade of Picton's division, was slain on the great breach. He was a leader greatly beloved by his Highlanders. There was in him a touch of the high-minded chivalry of Sir Philip Sidney added to the fire of Scottish valour. He, too, found at first a grave in the rugged and bloody slope where he fell; but the officers of the Coldstream Guards afterwards laid him in a statelier, but not a nobler, grave at Espega.

It is curious to note that after the capture of Rodrigo a number of British deserters-ten from the Light Division alone-were found in the garrison. They had fought desperately against their countrymen in that wild night of the assault. Most of them were shot, after trial by court- martial.

The capture of Ciudad Rodrigo is a memorable stage in the fortunes of the Peninsular War. It marks the beginning of that chain of almost unbroken victories which stretches to Waterloo. Wellington had accomplished with 40,000 men in twelve days, and in the depth of winter, what took Massena in 1810, with 80,000 men, and in the height of summer, more than a month to accomplish.

"Whether viewed in its conception, arrangements, or execution," the capture of Ciudad Rodrigo, says Jones, in his Journal of Sieges, "must be ranked as one of the happiest, boldest, and most creditable achievements in our military annals." Perhaps the best testimony to the splendour of the deed is found in the astonished explanations of it offeTed by the French.

On January 16 Marmont announced he was about to set out with 60,000 men to relieve Ciudad Rodrigo. "You may expect events," he added, "as fortunate and as glorious for the French army."

But on the 19th Ciudad had fallen. "There is something so incomprehensible in this," he wrote to the Emperor, "that I allow myself no observation!"

Napoleon, on his part, allowed himself a good many "observations" on the event, and of a kind very unsatisfactory to the generals to whom they were addressed!

On the morning after the assault Picton came up to the 88th as it was falling into line. A soldier shouted to him as the grim-faced Picton rode by, "General, we gave you a cheer last night; it's your turn now."

Picton took off his hat with a laugh, and said, "Here, then, you drunken set of brave rascals! Hurrah! We'll soon be at Badajos!"

The men shouted and slung their firelocks: the band broke into music, and, with a quick. step, the regiment moved off to the yet wilder and more desperate assault on the castle at Badajos.

Chapter XXIII: Siege for Badajos

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com