After the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo Marmont drew

back to Valladolid to wait for Wellington's next move. The

British general handed the captured city over to the

Spaniards, by whose careless hands it was perilously

neglected, and himself returned to Gallegos, there to mature

his plans for a rush on Badajos. The French marshals,

fluttered by Wellington's bold stroke, were keenly on the

alert; and Marmont, to do him justice, suspected that

Badajos would next be attacked.

After the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo Marmont drew

back to Valladolid to wait for Wellington's next move. The

British general handed the captured city over to the

Spaniards, by whose careless hands it was perilously

neglected, and himself returned to Gallegos, there to mature

his plans for a rush on Badajos. The French marshals,

fluttered by Wellington's bold stroke, were keenly on the

alert; and Marmont, to do him justice, suspected that

Badajos would next be attacked.

Jumbo Map of Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo (very slow: 254K)

Napoleon, however, laughed at the idea. "You must suppose the English mad," he wrote, "to imagine they will march on Badajos leaving you at Salamanca; that is leaving you in a situation to get to Lisbon before them."

Yet it was exactly this heroic "madness" which Wellington contemplated. He resolved to invest the place during the second week in March, when the flooded rivers would make it difficult for the French columns to concentrate for its relief. Meanwhile he covered his preparations with a mask of profoundest secrecy.

The guns for the siege were shipped at Lisbon for a fictitious destination, transhipped at sea into small craft, in which they were carried up the river Sadao, thence by bullock-trains through unfrequented routes to Badajos. The hunger-wasted bullocks, however, proved unequal to the task of dragging all the guns to the front, and the siege train was hopelessly inadequate. Some light guns were borrowed from the fleet, and stray pieces picked up in various quarters, making the most composite and utterly inadequate artillery train with which a great siege was ever undertaken. It included Spanish guns as old as the Armada, others that were cast in the reign of Philip III; yet others in that of John IV of Portugal.

Wellington had to pay in the blood of his soldiers for the defects in his battering equipment. Badajos was commanded by Philippon, a soldier of high daring and of exhaustless artifice; its garrison, 5000 strong, was made up of detachments from the forces of Marmont, of Soult, and of Jourdan, so that the honour of three armies was pledged to its succour. Wellington employed the 3rd, the 4th, and the Light Divisions, and a brigade of Portuguese in the siege; Hill and Graham commanded the covering force.

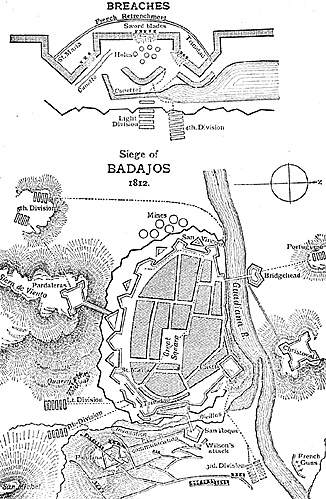

Badajos stands on a rocky ridge, a spur of the Toledo range, just where the Rivillas runs almost at right angles into the Guadiana, and in the angle formed by their junction. The city is oval in shape, ringed with strong works, the Rivillas serving as a wet ditch to its east front, the Guadiana, 500 yards wide, forbidding attack from the north; five great fortified outposts-St. Roque, Christoval, Picurina, Sardelifas, and a fortified bridge-head across the Guadiana, constituting the outer zone of its defences. The equinoctial rains were falling on Badajos when the siege began. The rivers were in flood; the ground was little better than a marsh; tempests were perpetually blowing.

Yet, from the moment the siege began, the thunder of the attack never ceased. Wellington attacked the city at its southeastern angle, where a curve of the Rivillas acted as a gigantic wet ditch. Here the Picurina, a formidable redoubt, with a ditch fourteen feet deep, and a rampart sixteen feet high, served as an outpost to the defences. Trenches were opened against the Picurina, but the business of forming trenches in earth of the consistency of liquid mud may be imagined, as well as the difficulty of placing and working guns under such conditions.

On March 25, however, fire was opened on the Picurina; then, impatient of the feebleness of his artillery, Wellington resolved to carry the fort with the bayonet.

At nine o'clock that night 500 men of the 3rd division in three tiny columns, led respectively by Shaw of the 74th, Powis of the 83rd, and Rudd of the 77th, leaped from the trenches and dashed at the great redoubt. One column was launched at the face of the work, the flank columns assailed its rear and sides, The distance was short, the troops quick, but the moment the men showed clear of the trenches the Picurina opened its fire, and every gun from Badajos that commanded their line of approach added its thunder to the tumult.

The palisades were reached; some were hewn down, but the weight of the fire forbade the stormers entering through the gaps. On the face of the work there was a ledge half-way up its front; the stormers reached this, pulled up their ladders, re-erected them on the ledge, and struggled up them to the top of the parapet. Here the French met them gallantly, and in the light of the incessantly darting musketry there could be seen from the trenches the dark figures contending fiercely on the parapet.

Kempt, who was in charge of the attack, now sent his reserves forward at a run; they reached the broken palisades, and stormed in, and the Picurina was carried. The fight lasted an hour. It had two armies as spectators, and the British loss in killed and wounded amounted to 316 out of 500 combatants.

With the capture of the Picurina the English were able to establish their breaching batteries within 300 yards of the body of the place, and for twelve days there raged a desperate duel betwixt the trenches and Badajos, maintained with the fiercest energy and accompanied with great slaughter. By April 6 three breaches were established; one in the face of the Trinidad bastion, one on the flank of the bastion of Santa Maria, and a third breach betwixt these two.

Soult was advancing fast for the relief of the city, and Wellington resolved to attack.

It was Easter Sunday, April 6. At half-past seven the breaching guns were to cease their fire and the attacking columns to leap from the trench. Later, the time for the assault was changed to ten o'clock, but no corresponding change of order was given to the breaching batteries; an apparently trivial, but in reality very tragical blunder. The guns ceased their thunder at half-past seven. Then followed two hours and a half of quietness, during which Phillipon was able undisturbed to cover the front of the breach with harrows, crows'-feet, grenades, &c., and to stretch across the gap in the parapet that terrible chevaux-de-frise of glittering sword-blades against which the stormers were to press their desperate bodies in vain.

Had the breach, or its crest, been swept by a tempest of grape till the moment the stormers were let loose, the lives of many hundreds of gallant men would have been saved. It is said, however, the batteries lacked ammunition for such a fire -- so inadequate were Wellington's resources for the siege!

If we omit two attacks which were mere feints, five great assaults were to be delivered on Badajos. Picton, with the 3rd division, was to cross the Rivillas, and escalade the castle. Leith, with the 5th division, was to attack the bastion of San Vincente, a powerful work against which no breaching shot had yet been fired. The Light Division, under Barnard, was to attack the smaller breach in Santa Maria; the 4th division, under Colville, was to storm the great breach in the Trinidad, and a detachment of the 4th division was to carry the breach in the curtain between Santa Maria and the Trinidad.

Of these five attacks, perhaps that on the third breach was the easiest; and it was never made i The party detailed for its assault was caught in the tumult of the fight at the great breach, and the next morning, while the other two breaches were strewn thick from foot to summit with the bodies of the slain, not one fallen body lay on the third breach.

Of the other four attacks, those on the castle and on San Vincente succeeded where success seemed impossible, and this decided the fate of the city. It is the paradox of the siege that, having formed three practicable breaches, after twenty days' battering, the assault succeeded at not one of the three. The city was escaladed, and carried at two other points deemed too strong for attack by gunfire, and against which not a cannon-shot had been discharged! The smaller breach in the flank of Santa Maria was assailed only for a few minutes and by an isolated party. The storming columns got mixed together, and the three separate attacks were melted into one-a confused, furious, long-sustained assault on the great breach, that failed-or, rather, that failed until the French were shaken by knowing that the castle had been carried, and were taken in the rear by the victorious stormers of San Vincente.

The escalade of the castle seemed a task beyond the power of human valour to accomplish. The castle stood on a rock 100 feet high; the walls rose to a height ranging from 18 feet to 24 feet; the crest of the parapet was lined with loaded shells, huge stones, logs of wood, &c., ready to be flung down on the attacking party. The soldiers holding the crest had each six muskets lying loaded by his side, they were furnished with long poles shod with iron, with which to thrust down the ladders. A fringe of steel and the flashes of rolling musketry volleys threatened death to the daring stormers as they clambered up their shaking ladders.

The men of the 3rd division were standing silent in the trenches waiting for the signal, yet half-anhour distant, when a lighted carcass flung from the castle revealed the long line of waiting soldiers. Picton was to lead, but bad not yet come to the front. Kempt, his second, a fine soldier, instantly took forward the division.

The Rivillas had to be traversed by a narrow bridge which the musketry -of the castle smote as with a whip of flame. The men crossed in single file, were re-formed under fire, and led up the rocky slope to the foot of the castle walls. Here Kempt fell, and, as he was carried back, met Picton, black with anger and furious with haste hurrying to the front. The whole assault of Badajos by this time was lot loose. Leith Hay at the western extremity was flinging himself on San Vincente, the men of the Light Division and of the 4th were racing forward to the two breaches. Badajos, from every bastion, and from the long curving crest of its walls, was pouring out its fire. Surtees, who watched the scene from the quarries, says the darting flames were so bright. and incessant that he could plainly see the faces of the defenders, though nearly a mile off! Yet against a fire so dreadful the stormers raced forward with reckless daring.

The men of the 3rd meanwhile had placed their ladders against the lofty walls of the castle, and were crowding up them. The shouts, the crackle of musketry, the roar of the guns, the sound of the crashing ladders as they were broken by the huge stones flung on them, the ring of steel against steel as the men on the ladders which yet stood strove to force their way on to the parapet, made the wildest tumult.

Pakenham, Wellington's brother-in-law, who afterwards died in front of New Orleans, was one who reached the crest, only to be thrust down it with a bayonet stab. But the advantage was with the defenders, and for a moment the men of the 3rd drew back, broken but furious.

"If we cannot win the castle," Picton cried wrathfully to his soldiers, "let us die upon the walls!" The men were reformed, and two officers, Colonel Ridge and an ensign named Cauch, seized a ladder and ran forward with it to a new spot, where the wall was slightly lower. Another ladder was brought to the same spot, the men streamed furiously up, and the castle was won; but Ridge, with many another gallant soldier, died on the ramparts.

One of the first to mount was Lieutenant Macpherson of the 45th. On reaching the top of the ladder he found it still below the crest. Accordino, to his own story he "shouted 'directions to those below, and, pushing the head of the ladder from the wall, the men below, seizing its lowest rung, lifted him bodily to the summit."

Here a French soldier deliberately put his musket against his body and fired. The ball struck a metal button on his coat and glanced off, but not without driving two fractured ribs in upon his lungs. Pakenhain, who was next below him, tried to clamber past his wounded friend, but in vain; and at that moment the ladder broke. Macpherson lay long insensible at the foot of the wall, but recovered consciousness, clambered into the castle, and had the satisfaction of pulling down and capturing the French flag that flew above it.

Picton found that the gates which led from the castle into the town were walled up, and the slaughter amongst his own men had been so dreadful that for the moment he was content with holding the castle he had won, instead of breaking through to take the other breaches in flank.

Leith Hay, in his turn, had succeeded at San Vincente, and this, too, where success seemed impossible. The ditch was 6 feet deep, the scarp 30 feet high, the glacis rained, the parapet fringed with veterans.

The Portuguese battalions, appalled by the fire poured upon them, flung down their ladders and fled. But the British caught up the ladders, broke through the palisade, leaped into the ditch-only to find the ladders too short. A mine was sprung under their feet, they were pelted with musketry from above, their ladders broken with huge stones. Yet the stubborn British persevered.

At one spot the bastion was lower, and the ladders were replaced here. One soldier was thrust by his comrades up and over the crest, others followed, and the bastion was won.

The five assaults of that night were alike in heroism, but the tragedy of the struggle reached its climax at the great breach, or rather at the two breaches. The storming parties of the two columns raced side by side to the ditch, bags of hay were thrown into it to lessen its depth, ladders placed down the counterscarp, and in a moment the ditch was crowded with gallant soldiers. At that instant a mine beneath it was exploded: it became a sort of crater of flame in which perished, almost at a breath, hundreds of brave men.

The red flame lit up for a moment the whole face of Badajos, with its crowded parapets and madly-working guns. The men of the Light Division, coming on at a run, reached the edge of the smoking ditch just after the explosion, and stood for an instant amazed at the sight.

"Then," says Napier, "with a shout that matched even the sound of the explosion, they leaped into it, and crowded up the breach."

The 4th division came running up with equal fury to attack the middle breach, but the ditch was deep with water, and the first eager files that sprang into it were trodden down by their comrades, and "about a hundred of the Fusiliers, the men of Albuera," perished there.

It illustrates the confusion of a night attack that the stormers of the Light Division were on the point of firing into an unseen body coming up on their flank, which proved to be the stormers of the 4th division, coming up at a run to join them.

In front of the Trinidad bastion itself the ditch was very wide, its centre occupied by a high unfinished ravelin. The men eagerly climbed up this, believing it to be the foot of the breach. They found instead there gaped before them, wide and black and deep, yet another ditch. They must leap into its dark and muddy depths and clamber up its farther side before reaching the real foot of the breach.

That unhappy ravelin undoubtedly broke the rush of the stormers. The men gathered on its summit and began to fire back at the parapets. The Light Division, too, in the darkness and tumult, had mistaken its path. Its men crowded to the ravelin by the side of their comrades of the 4th division, and, in the noise and madness of the scene, it was impossible to withdraw the men of the Light Division and lead them to their assigned point of attack.

The leaders of the attacking columns, leaping from the crowded ravelin into the farther ditch, led the right way up the breach; but it was impossible to re-form the columns, and set them in ordered and disciplined movement up its rough slope; and only by the momentum of a column in regular formation could the obstructions that barred the breach be swept aside. Here was the great chevaux-de-frise, set with sharpened sword-blades. Behind it was a triple rank of infantry firing swiftly. Loaded shells were rolled down amongst the English, guns from either flank smote them incessantly with grape.

"Never," says Jones, in his history of the siege, "never since the discovery of gunpowder were men more seriously exposed to its action than those assembled in the ditch to assault the breaches. Many thousand shells and hand-grenades, numerous bags filled with powder, every kind of burning composition and destructive missile had been prepared, and placed behind the parapets of the whole front. These, under an incessant roll of musketry, were hurled into the ditch, without intermission, for upwards of two hours, giving its whole surface an appearance of vomiting fire, and producing occasional flashes of light more vivid than the day, followed by momentary utter darkness."

In that wild scene disciplined order had perished, The impulse of attack had to be supplied by the daring of individual leadership, and this did not fail. Every other moment an officer would spring forward with a shout, and climb the breach; a swarm of gallant men would follow. They swept up the slope like leaves driven by a whirlwind; they seemed to shrivel in the incessantly-darting flames that streamed from the crest, they were driven back again like leaves caught in an eddy of the winds.

Again and again, a score of times over, that human wave flung its spray upon the stony slope of the breach; and each time the wave sank back again; but the charging parties seldom numbered more than fifty at a time. For two hours that scene raged. The British, unable to advance and scorning to retreat, at last stood on the slope and crest of the ravelin or in the ditch below, leaning on their muskets and looking in sullen fury at the breach, while the French, shooting swiftly from the ramparts, asked tauntingly "why they did not come into Badajos."

An officer who stood amongst the sullen groups in the ditch says, "I had seen severe fighting often, but nothing like this. We stood passively to be slaughtered."

Shaw Kennedy fixes on one British sergeant named Nicholas as the hero of the wild fight on the breach. "Nicholas," says Kennedy, "seemed determined to tear the sword-blades of the chevaux-de-frise from their fastenings, in which attempt he long persevered while enveloped in an absolute stream of fire and bullets poured out against him by the defenders. Nicholas was the hero of the Santa Maria."

Wellington, his face sharpened end grey with anxiety, was watching the scene from an advanced battery, and he now ordered the division to fall back from the great breach, intending to re-form it, and attack afresh in the morning. But the men could not be brought to retreat. The buglers of the reserve were sent to the crest of the glacis to sound the retreat, but the men on the ravelin and in the ditch would not believe the signal was genuine, and struck their own buglers who attempted to repeat it.

"I was near Colonel Barnard after midnight," says Kincaid, "when he received repeated messages from Lord Wellington to withdraw from the breach, and to form the division for a renewal of the attack at daylight; but, as fresh attempts continued to be made, and the troops were still pressing forward into the ditch, it went against his gallant soul to order a retreat while yet a chance remained. But, after heading repeated attempts himself, he saw that it was hopeless, and the order was reluctantly given about two o'clock in the morning. We fell back about 300 yards, and re-formed-all that remained to us."

A few men of the Light Division, under the leadership of Nicholas of the Engineers and Shaw of the 43rd, had found the breach in the Santa Maria bastion which their column was meant to carry. They were only about fifty in number, but Nicholas and Shaw led them with a rush up the ruins. Nicholas fell mortally wounded; well- nigh every man of the party was struck down, except Shaw. He stood alone, and taking out his watch, he declared it "too late to carry the breach that night," and walked down the breach again! Nicholas, who died of his wounds a few days afterwards, told the story of Shaw's amazing coolness.

Meanwhile Leith Hay's men from San Vincente were marching at speed across the town, through streets silent and empty, but lit as for a gala, with light streaming from the houses on either side. They fell in with some mules carrying ammunition to the great breach, and captured them, and then advanced to attack the defenders of the great breach from the rear.

A battalion of the 38th, too, had advanced along the ramparts from San Vincente, and opened a flank fire on the breach. The French knew that the castle was lost, and, attacked both on flank and front, they gave way at the breach. The men of the 4th and of the Light Divisions were sent forward again. The breach was abandoned and Badajos was won!

For long, to Wellington and his staff watching from an advanced battery the fury of the assault no cheerful news came. The red glare on the night sky, the incessant roll of musketry, the wild shouts of the stormers, answered with vehement clamour from the walls, showed that success had not yet been won. But when the 44th had gained the ramparts of San Vincente its bugler sounded the advance.

Wellington's quick ear caught through the tumult of the night that sound. "There is an English bugler in that tower," he said. This was the first hint of success which reached him; then came a messenger from the castle. It was Picton's aide-de-camp to tell of the place having been carried.

Five-sixths of the attacking party had fallen; of Pieton's invincible soldiers little more than a scanty handful held the great castle, whose towering height and strength seemed to defy attack. Picton himself, after describing how his men lifted one another up till the wall was gained, added, "Yet I could hardly make myself believe that we had taken the castle."

The news was sent to the men Of the 4th and the Light Divisions after they had fallen back. No one at first would believe it, so incredible did it seem to the assailants of these impregnable breaches that any troops could have entered the place. The men and the officers were lying down in sullen exhaustion after their conflict, when a staff officer came up with the orders to immediately attack the breach afresh.

"The men," says the History of the Rifle Brigade "leaped up, resumed their formation, and advanced as cheerfully and as steadily as if it had been the first attack."

According to Costello, who took a gallant part in that wild scene, the first intimation the-British stormers at the great breach had of Picton's success was an exultant shout from within the town itself, followed by a cry in rich Irish brogue, "Blood and 'ounds! Where's the Light Division? The town's our own! Hurrah!"

The men of the triumphant 3rd division thus were calling across the breach to their comrades of the Light Division.

When they clambered the breach, passing over the hill of the dead, and reached the chevattx-de-frise, there was no resistance. There were no darting musketry flames to drive them back. Yet it was with difficulty they forced even the unguarded barrier!

When the soldiers at last broke through into Badajos, their passions were kindled to flame, and the scones of horror and rapine which followed were wilder than even those at Ciudad Rodrigo. But there was an element of humour amid even the horrors of that wild night.

"Wherever," says Kincaid, "there was anything to eat or drink, the only saleable commodities, the soldiers had turned the shopkeepers out of doors, and placed themselves regularly behind the counter, selling off the contents of the shop. By-and-by, another and a stronger party would kick those out in their turn, and there was no end to the succession of self-elected shopkeepers."

In that wild night-struggle the British lost 3500 men, and most of these were slain within an area, roughly, of a few hundred yards square. It is said that Wellington broke into tears -- the rare, reluctant tears of a strong man - - as he looked on the corpsestrewn slope of the great breach.

Blakeney, who served with the 28th, describing the breach, says that "boards, fastened with ropes to plugs driven in the ground within the breach, were let down, and covered nearly the whole surface of the breach. These boards were so thickly studded with sharp-pointed spikes that one could not introduce a hand between them. They did not stick out at right angles to the board, but were all slanting upwards."

In the rear of the breach thus covered with steel points, "the ramparts had deep cuts in all directions, like a tanyard, so that it required light to enable one to move safely through them, even when no fighting was going on."

Only two British soldiers had actually forced their way through these dreadful obstacles, and reached the ramparts, where their bodies were found in the morning. Blakeney supplies one dreadful detail of the scene presented by the breach and its approaches on the morning after the fight. The water in the great ditch was literally turned crimson with the bloodshed of the night; and, as the sun smote it, the long deep ditch took the appearance of "a fiery lake of smoking blood, in which lay the bodies of many British soldiers."

The siege only lasted twenty days, and its success proved more difficult of explanation to French marshals than even that of Ciudad Rodrigo.

"Never," wrote Kellerman, " was there a place in a better state, better supplied, or better provided with troops. I confess my inability to account for its inadequate defence. All our calculations have been disappointed. Lord Wellington has taken the place, as it were, in the presence of two armies, amounting to 80,000 men."

But the defence of Badajos was not inadequate. It was skilful and gallant in the highest degree. What explains the capture, in a time so brief, of a place so strong, and held with such skill and power, is the matchless valour of the British troops. The fire and swiftness of the siege, it may be added, outraced all the calculations of Marmont and Soult. Soult, in fact, only reached Villafranca, nearly forty miles from Badajos, on April 8, when he learnt to his amazement that the place had fallen!

Chapter XXIV: Wellington and Marmont

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com