Meanwhile, on March 6, the day after Massena

commenced his retreat from Santarem, and five days

before Soult captured Badajos, a great blow had been

struck at the French arms in front of Cadiz, a blow which

recalled Soult abruptly to the south, and helped still

further to defeat Napoleon's plans for the conquest of

Portugal.

Meanwhile, on March 6, the day after Massena

commenced his retreat from Santarem, and five days

before Soult captured Badajos, a great blow had been

struck at the French arms in front of Cadiz, a blow which

recalled Soult abruptly to the south, and helped still

further to defeat Napoleon's plans for the conquest of

Portugal.

Victor, with 20,000 men, held Cadiz blockaded, and Graham, who commanded the English contingent in Cadiz, as soon as he knew of Soult's march northward framed a bold scheme for driving Victor from his lines. Napier describes Graham as "a daring old man and of ready temper for battle." He was a soldier by natural genius rather than by training.

A Scotch laird, with Scottish shrewdness in his brain and the martial temper of a fighting clan in his blood, Graham had outlived his youth when, driven by domestic grief, he sought consolation in a soldier's life. In 1794, when he was nearly fifty years of age, he raised a regiment of Scottish volunteers, afterwards the famous 90th. He served in Egypt as colonel of that regiment, was aide-de-camp to Moore at Corunna, commanded a brigade at Walcheren, and was in 1810-11 in command of the British garrison at Cadiz. Graham's face reveals his character-strong, shrewd, manly; not the face of a diplomatist or of a statesman, perhaps, but the face of a man capable of standino, unshaken in disaster, and from whose look and bearing in the hour of danger weaker men would catch courage.

Graham's Plan

Graham's plan was to sail from Cadiz, land at Algesiras, march inland, and fling himself on Victor's rear. La Pena, the Spanish Captain-General, with 7000 Spaniards, was in command; Graham had 4000 British troops. It was a perilous, not to say rash, attempt. A mixed force of less than 12,000 Men, of whom 7000 were Spaniards, and under a Spanish general, were to attack 2opoo French troops under a famous French marshal. There was no element of surprise, moreover, in the expedition. Victor knew exactly his enemy's plans.

The expedition, with sonic difficulty, landed at Algesiras, and La Pena illustrated all the characteristics of Spanish generalship in the operations which followed. He scorned counsel; he took no precautions. He rambled on, as though engaged in a picnic, ran his army into an almost hopeless position, and then allowed his British allies to do all the fighting.

On March 5 Victor found La Pena marching across his front from Barossa, a coastal ridge, rugged and low, to the parallel ridge of Bermega, some five miles distant. Victor had in hand three divisions commanded by Laval, Ruffin, and Villatte, making a force of 9000 good troops with fourteen guns. He thrust Ruffin's division in column past Graham's rear, and seized the Barossa height, while Laval moved to strike at Grahain's flank.

La Pena meanwhile marched off into space with great diligence, some companies of Walloon guards and some guerilla cavalry alone wheeling round as the roar of the guns broke out behind them, and coming up to aid Graham. Graham thus found himself suddenly assailed by a French army double his own in numbers; his Spanish allies were hurrying off beyond the horizon; one French column was in possession of his baggage, and another about to smite him on the flank.

Graham's rear-guard consisted of the flank companies of the 9th and 82nd, under Major Brown. Graham sent him the single message, "Fight" then, with instant decision, he wheeled his columns round, sent one of his divisions under General Dilkes to storm the Barossa ridge, and launched the other, under Wheatley, against Laval. Duncan's guns, attached to Wheatley's brigade, opened a rapid fire on Laval's columns, whilst Barnard took his riflemen out at speed and skirmished fiercely with the enemy.

The contest with Laval was determined by a rough, vehemently sustained charge of the 87th and three companies of the Coldstreams. It was a charge which for daring almost rivalled that of the Fusiliers at Albuera, and Laval's massive battalions were simply wrecked by it.

Brown, meanwhile, obeying Graham's orders literally, was standing in the path of Ruffin's whole force, fighting indomitably with half his men down. Dilkes' brigade came up at the double. The hurrying regiments saw before them Brown's gallant companies dwindled to a handful, yet fighting desperately against a whole French division. The English regiments, roused to passion at the sight, did not pause to fall into line, but stormed up the ridge, and were met by the French with a courage as high as their own. Ruffin himself was slain; his second in command fell mortally wounded.

By the mere strength of their attack, and the swift and thundering volleys, which clothed their front with a spray of flame, the British broke the French columns and drove them from the ridge with the loss of three guns.

The fight lasted only an hour and a half; for suddenness and for fury it is not easily paralleled. But on the part of the British it represents a very gallant achievement. Deserted by their allies, they yet overthrew a force more than double their own in number, with the loss to themselves of 1200 killed and wounded. Every fourth man in the British ranks, that is, was struck down. The French killed and wounded amounted to 2300, two of their generals were slain, they lost six guns and an eagle, and 500 prisoners. The victory was due mainly to Graham's instant resolve to attack, a resolution so wise and so sudden that, says Napier, it may well be described as "an inspiration." But even Graham's generalship would have been in vain had it not been for the stern valour and warlike energy of his incomparable troops.

Usual Spanish Mode

La Pena watched the battle as a remote and disinterested spectator; but when the victory was won, he appeared on the scene to claim the glory of the fight, and to accuse Graham of disobedience to his orders! La Pena, it may be added -- again in the characteristic Spanish fashion -- refused to assist the British by either supplying food for the living or helping to bury the dead.

Graham, in a mood of dour Scotch fury, marched his men off the battlefield, and refused further co-operation with this remarkable ally. In a sense Barossa was a barren victory. Victor remained in possession of his lines in front of Cadiz; but the shock of Graham's feat brought Soult back into Andalusia, and so helped to make impossible any combination with Massena.

The Spanish Cortes conferred on Graham a grandeeship of Spain, with the title of "Duke of the Cerro do la Cabeza del Puerco."

That title in Spanish is sonorous and imposing. Translated into English it simply means "Duke of the Hill of the Pig's Head" -- the local name of Barossa. Graham, however, had lost his regard for all things Spanish, and declined a title so curious.

Frontier Fortresses

The campaign for the rest of the year eddies round the great frontier fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo, Almeida, and Badajos. Wellington was resolute to capture these, the French generals were keen to hold them. If strongly held, Badajos would stand as a rocky bar betwixt two great French armies of the north and south, and make any concert betwixt them impossible. Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo stood in the path of any invasion of Portugal from the north.

Massena guarded Almeida. Soult had charge of the defence of Badajos. Wellington was now blockading Almeida; twice he attempted to besiege Badajos, but each time the attempt drew upon him some overwhelming combination of French armies, and the two great battles of 1811, Fuentes d'Onore and Albuera, were part of the price the British troops had to pay for the explosion which threw Almeida into the hands of Massena, and the treachery of the Spaniard who sold Badajos to Soult.

Wellington on April 21 put Beresford, with 20,000 infantry, 2000 cavalry, and eighteen guns, in charge of the operations for the capture of Badajos. As a preliminary he had to relieve Campo Mayor, then besieged by Mortier. Campo Mayor, as a matter of fact, had surrendered on March 2 1, and Beresford only reached the place four days after its fall, on March 25. It was promptly recaptured, the fighting round the place being made noteworthy by a memorable charge of the 13th Dragoons under Colonel Head. A French convoy, with battering train, had just moved out of Campo Mayor on its way to Badjos, under the guard of a strong cavalry force; and the 13th, with some Portuguese squadrons under Otway, were launched at the convoy.

The French horsemen gallantly turned on them. The squadrons met at full gallop with loose reins and raised swords, and neither side flinched. The English, riding more compactly, broke through the French, wheeled, and once more rode through them. The French finally gave way and scattered, and the 13th, with the rapture of battle in their blood, galloped on, cut down the riders of the battering train, and rode up to the very bridge of Badajos. The French lost 300 men and a gun. A corporal of the 13th slew the colonel of the 26th French dragoons in single combat, cleaving his head in twain.

Had the furious ride of the 13th been adequately sustained, the French would have lost their entire battering train, and the defence of Badajos would have been almost destroyed. Wellington displayed sometimes a curious impatience with exploits of this character; they won from him nothing but acrid and mis-timed rebuke. "The conduct of the 13th," he wrote, "was that of a rabble, galloping as fast as their horses would carry them over a plain after an enemy to whom they could do no mischief when they were broken."

"If the 13th Dragoons," he added, "are again guilty of this conduct, I shall take their horses from them."

"The unsparing admiration of the whole army," Napier says significantly, "consoled them for that rebuke."

Beresford, as a matter of fact, lacked exactly that element of fiery dash which the 13th displayed so magnificently at Campo Mayor, and his slowness enabled Philippon, who was in command of Badajos, to close its breach and repair its defences, and so made possible the bloodiest and most disastrous siege of the Peninsular war.

Wellington was now blockading Almeida and besieging Badajos at the same moment. It was certain that Massena would march to the relief of Almeida, and Soult strike hard in defence of Badajos. To maintain his attack on these two fortresses, Wellington must fight; and so there followed the two great battles of Fuentes d'Onore and Albuera.

Beresford opened his trenches before Badajos on April 21, and Wellington reckoned that he had three weeks in which to carry the place. By that time Soult would certainly appear to relieve it. But before that period expired Massena was moving from Salamanca in order to raise the blockade of Almeida, and Wellington marched to meet him. Drouet had joined Massena with 11,000 infantry and cavalry, and he had now a force of 46,000 good soldiers, including 5000 cavalry. Wellington, on the other hand, had only 32,000 infantry, 1500 cavalry, and 42 guns.

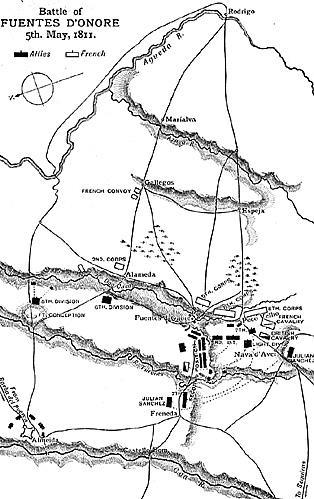

On May 3, Wellington took up a position on a tableland in front of Almeida, his left resting on Fort Conception, his right being behind the village of Fuentes d'Onore, with the Coa in his rear. This was the weak point in his position. If driven back, all his guns must cross by a single narrow bridge -- a perilous operation with a victorious foe hanging on his rear. Massena's plan was to turn the British right by carrying the village of Fuentes, seize the only bridge across the Coa, and then fling his overwhelming cavalry strength on the British centre and left, and drive Wellington's broken army into the Coa.

Fuentes

Fuentes

Fuentes was held by some light companies from the 1st and 3rd divisions, and on the evening of the 3rd Loison made a desperate attempt to carry the village. The attack of the French was urged with such fire, and was so overpowering in strength, that the light companies holding the village were driven, stubbornly fighting, through the streets to its very skirts.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Fuentes d'Onore (very slow: 232K)

Then the 24th, the 71st, and the 79th regiments, coming down swiftly from the high ground above Fuentes, drove the French in turn from the village. The 71st was largely a Glasgow regiment, and its colonel, Cadogan, as be took them forward to the charge, shouted, "Now, my lads, let us show them how we can clear the Gallowgate."

The sound of that homely name, with all its associations, kindled the Scotsmen. The French stood their ground gallantly, and as a result there came the actual clash of opposing bayonets.

"The French," says Alison, with a touch of uncomfortable realism, "were driven back literally at the bayonet's point, and some who stood their ground were spiked and carried back some paces on the British bayonets."

The French were finally swept through Fuentes, and driven in disorder across a rivulet on its further side. The 71st, eagerly following, saw across the rivulet what, in the dusk, they took for a French gun. They charged eagerly through the stream and the gloom, and carried it off in triumph-to discover it was only a tumbril.

On the 4th Massena made a careful study of Wellington's position. It had the weakness of being too far extended. On the urgent counsel of Sir Brent Spencer, Wellington had prolonged his right to hold a hill considerably beyond Fuentes, and his battle-line now covered a front of seven miles. This was one of the rare occasions on which Wellington took somebody else's advice, and the advice was wrong. A line so extended was necessarily weak, and gave Massena a chance which he eagerly seized. His plan was to roll back Wellington's too- extended right wing, and at the same moment carry the village of Fuentes, so as to cut the attacked wing clean off from the British centre. The tactical story of the battle may be told almost in a sentence.

The attempt to carry Fuentes failed, and Wellington saved his right wing by swinging it back, through the central fury of the fight, to a position at right angles with his line -- a memorable feat of coolness and discipline.

On the morning of the 5th the battle opened with a brilliant charge of French cavalry. They came on in overpowering strength, lancers, dragoons, cuirassiers, glittering with steel and gay with tossing plumes. The English had not more than 1000 sabres on the field, while the French had 29 squadrons of cavalry, including 800 horsemen of the Imperial Guard. The British cavalry were thrust back, gallantly fighting, by the mere weight of the French masses.

Ramsay's battery of horse-artillery disappeared in the rush of the French squadrons, and the shout was raised, "Ramsay is cut off!" Montbrun's fiery horsemen, riding fiercely but in somewhat broken order, s wept onward to the steady ranks of the 7th division. They had captured a British battery, and they were eager to break a British square! But as they rode, to quote a fine passage from Napier, "a great commotion was observed in their main body: men and horses were observed to close with confusion and tumult towards one point, where a thick dust and loud cries, and the sparkling of blades and flashing of pistols, indicated some extraordinary occurrence. Suddenly the multitude became violently agitated, an English shout pealed high and clear, the mass was rent asunder, and Norman Ramsay burst forth, sword in hand, at the head of his battery; his horses, breathing fire, stretched like greyhounds along the plain, the guns bounded behind them like things of no weight, and the mounted gunners followed close, with heads bent low, and pointed weapons, in desperate career." Ramsay, in a word, at the sword's point, and by sheer hard fighting, had broken loose from his captors and brought off his guns.

Wellington had quickly realised that his position was too extended, and he had to take in band the perilous task of swinging his right wing back, using Fuentes as a pivot, across the plain, now practically held by the triumphant French horse, to a ridge that ran back at right angles from Fuentes. The ridge was pierced by a streamlet called the Turones, which ran across the plain to the rear of the position, at that perilous moment held by the two divisions -- the 7th and the Light -- forming the British right.

The 7th division had to ford the Turones and march along its farther bank to the ridge. The Light Division had to move across the open plain, and occupy, in line with the 7th, that part of the ridge betwixt the streamlet and Fuentes. Thus the two divisions, throughout this most perilous maneuvre, were divided by the Turones.

The task of the 7th division was comparatively easy, but that of the Light Division was one of the most perilous ever attempted in war. The plain was crowded with camp followers, baggage carts, etc. It lay open to the charge of the exultant French cavalry, and Montbrun's horsemen -- some of them cuirassiers of the Imperial Guard -- were riding fiercely beside the steady formation of the British, watching for an opportunity to charge. The Light Division squares in that confused scene appeared, says Napier, "but as specks," and these moving "specks" of dogged disciplined infantry were swallowed up in a mass of 5000 horsemen, " trampling, bounding, shouting for the word to charge."

But nothing shook the steady ranks of the Light Division. "The squares of bayonets," said one who watched the scene, "were sometimes lost sight of amid the forest of glittering sabres," but onward they moved as steady as fate.

Repeatedly Montbrun's dragoons galloped almost to the very points of the steady bayonets, but fell back before the rolling musketry volleys. Alternately halting and firing, the disciplined squares marched on. A rallying square of skirmishers, who had not had time to reach the regiment, was indeed broken by the French cavalry, but the lines of the Light Division were not even shaken. Massena ordered up the artillery of the Guard, but some delay occurred, and the French guns only reached the scene in time to open a distant fire on Houston's regiments.

Napier, who was an eye-witness, declares the French never came within sure shot distance of the Light Division. "That fine body was formed in three squares flanking each other; they retired over the plain leisurely, without the loss of a man, without a sabre wound being received. They moved in the most majestic manner, secure in their discipline and strength, which were such as would have defied all the cavalry that ever charged under Tamerlane or Genghis!"

The British divisions had now reached their new position, and Wellington's battle-line, though bent almost at right angles, was secure. Meanwhile it was part of Massena's plan that Drouet should carry Fuentes, the pivot of this movement, and so break the British line at the moment when Montbrun, it was expected, would be rolling back in mere ruin the extended British right wing. Drouet, carrying out this plan, attacked Fuentes d'Onore with great energy and fire. The 24th, 71st, and 79th clung obstinately to the village against vastly superior numbers but were driven from house to house, till they held merely the upper edge of the village.

The rolling of musketry volleys was incessant. The fighting was hand-to-hand. Two companies of the 79th were taken; Cameron, its colonel, was slain. The 74th and 88th were brought up to the fight. A French regiment, the 45th, distinguishable by the long red feathers in the headdress of its men, fought with splendid courage. Its eagle was planted on the outward wall of the village nearest the British position, and became the centre round which raged a furious battle.

When the gallant French regiment was at last driven back by a charge of the 88th, nearly 100 of its number were found dead around the splintered pole of its eagle. The slaughter amongst the 79th was great, and Costello says that after the fight was over, one of the Rifles collected in the village two arm's full of black feathers he had taken from the bonnets of the slain Highlanders.

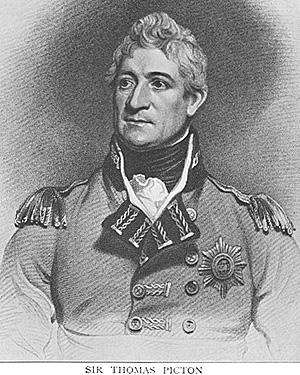

The charge of the 88th finally drove the French through the village with overwhelming fury. Picton, a few days before, had occasion to rebuke that regiment for some plundering exploits, and, in his characteristic fashion, told them they were "the greatest blackguards in the army."

Wellington, it will be remembered, described Picton as

being "a rough, foul-mouthed devil as ever lived." That was a

cruel exaggeration; but Picton no doubt was an expert in the

rough vernacular of the camp.

Wellington, it will be remembered, described Picton as

being "a rough, foul-mouthed devil as ever lived." That was a

cruel exaggeration; but Picton no doubt was an expert in the

rough vernacular of the camp.

When the 88th returned breathless, and with blackened faces, from the charge, Picton, waving the stick he always carried in his hand, shouted "Well done, the brave 88th."

Whereupon a voice from the ranks, in the rich brogue of Connaught, cried, "Are we the greatest blackguards in the army now?"

"No, no,"' replied Picton, "you are brave and gallant soldiers."

The ensign who carried the colours of the 79th in this dreadful struggle was killed. The covering sergeant immediately called out, "An officer to bear the colours of the 79th!" One came forward, and was instantly struck down. "An officer to bear the colours of the 79th!" again shouted the sergeant, and another hero succeeded, who was also killed. A third time, and a fourth, the sergeant called out in like manner as the bearers of the colours were successively struck down; till at length no officer remained unwounded but the adjutant, who sprang forward and seized the colours, saying, "The 79th shall never want one to carry its colours while I can stand."

When the French were driven out of the village the battle practically ceased. Massena lingered sullenly in front of the British position for two days.

On the 6th, by way of impressing the imagination of Wellington's battalions, he marched his finest regiments past the front of the British position. But the imagination of the British private is not susceptible to this kind of appeal.

"They looked uncommonly well," wrote an officer of the Rifle Brigade, "and we were proud to think we had beaten such fine-looking fellows so lately!" This was certainly not the reflection which Massena wished to excite in the British mind.

On the 7th Massena drew off. His attempt to raise the blockade of Almeida had failed, and while the losses of the British did not exceed 1500 men and officers, that of the French was more than double that number. The lanes, the churchyards, the gardens in the village of Fuentes were literally piled with their slain. It was the last battle Massena fought in the Peninsula. Marmont replaced him, and, with sorely damaged fame, Massena turned his back on Spanish battlefields.

Fuentes d'Onore is a fight which does credit to the warlike qualities of the British private, but does not add to Wellington's fame as a general; and though Massena failed to raise the blockade of Almeida, yet the garrison, by a desperate stroke, broke out of the fortress, having destroyed its guns and blown up its defences, and made their escape with comparatively little loss.

The drowsiness or the stupidity of a British officer made the escape of the French possible; and it was in reference to this incident that Wellington, with that touch of gall which sometimes flavoured his correspondence, wrote that he "began to be of opinion that there is nothing on earth so stupid as a gallant officer! "

When the escaping French reached the main body, Brennier, their chief, was carried in triumph through the French camp on his soldiers' shoulders. He had his own strong personal reasons for joy over his escape. He had already been a prisoner to the English, and had broken his parole; and he might have fared badly had he been recaptured.

Chapter XX: The Albueran Campaign

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com