Beresford was now besieging Badajos, and trying to

compensate with the blood of his gallant troops for a

hopeless inadequacy of siege material. That strong place,

however, guarded by the genius of Philippon, an

unsurpassed master in the art of defence, resisted all

assaults, and Soult was coming up by forced marches from

the south to raise the siege. Beresford abandoned his

attempt on Badajos, though his engineers promised to

carry the place in three days. Blake joined him with a

strong Spanish force, and on the 15th he was across the

Guadiana, and stood in position at Albuera, ready to

fight Soult.

Beresford was now besieging Badajos, and trying to

compensate with the blood of his gallant troops for a

hopeless inadequacy of siege material. That strong place,

however, guarded by the genius of Philippon, an

unsurpassed master in the art of defence, resisted all

assaults, and Soult was coming up by forced marches from

the south to raise the siege. Beresford abandoned his

attempt on Badajos, though his engineers promised to

carry the place in three days. Blake joined him with a

strong Spanish force, and on the 15th he was across the

Guadiana, and stood in position at Albuera, ready to

fight Soult.

At three o'clock on the afternoon of the 15th the French light horsemen were riding in front of the ridge of Albuera, while far beyond to the edge of the horizon clouds of whirling dust told of the speed with which Soult's columns were advancing.

Soult's force was inferior in numbers to Beresford's, but as far as martial qualities are concerned it was one of the finest armies that ever marched and fought under the French eagles. It numbered 19,000 infantry, 4000 cavalry, and 40 guns. The men were veterans, proud of their general, eager for battle, and confident of victory; and these are conditions under which French soldiers are very formidable.

Blake had joined Beresford with 15,000 Spaniards, bringing the British general's force up to 30,000 infantry, 2000 cavalry, and 38 guns. But of this composite force only 7000 were British; the Spaniards were ill-disciplined, ill-officered, and in a condition of semi-starvation. As the battle proved, they could stand in patient ranks and die, but they could not maneuvre. Blake was ignorant, proud, and fiercely jealous of the British commander-in-chief. He was of Irish blood, but kept nothing of the Irishman except the name. Blake had lost, in a word, all the virtues proper to the Irish character, and had acquired all the vices peculiar to the Spanish temper.

And Beresford was not, like Wellington, a great captain with a masterful will. He was a thirdrate general, who could neither meet with equal art Soult's strategy nor override Blake's obstinacy. Beresford, indeed, had already practically given away the battle to Soult by allowing that quick-witted and subtle commander to seize a wooded hill immediately under the British right wing, from which he could leap suddenly and with overpowering strength on the weak point of Beresford's position. All the conditions, in a word, were in favour of the French. There remained to Beresford only the unsurpassed fighting qualities of his British regiments.

In a sense these regiments were responsible for the stand Beresford was now making. Albuera, as far as the British were concerned, was a battle without a motive. It was not fought to cover the siege of Badajos, for that siege was already abandoned. But Beresford's regiments were eager to fight. They had taken no part in the recent combats under Wellington. Busaco had been fought and Fuentes d'Onore won without them, and, with a French army advancing to engage them, they were angrily reluctant to fall back.

It added to Beresford's difficulties that he had taken Hill's place in command of the army. The contrast between the placid Hill, an English country gentleman in a cocked-hat, and Beresford, a fiery Irishman, who was only a Portuguese general, and had, in addition, the bar-sinister across his name, was startling. Beresford could not hold, with easy and calm authority, the high-spirited troops under his command; and that circumstance goes far to explain why Albuera was fought. Beresford himself, on his fighting side, sympathised with his men, and the general in him was not wise enough nor masterful enough to conquer the mere blind combative impulse which drove him and his troops to make a dogged stand.

Battle of Albuera

Battle of Albuera

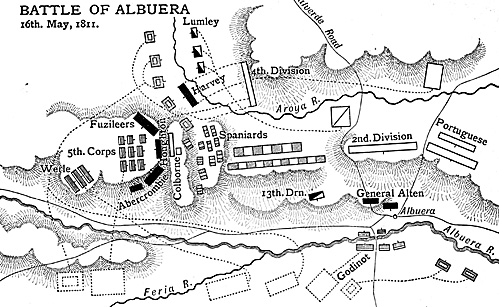

The scene of the battle is a line of hills along whose eastern front flows the river Albuera. The hills are high; the eastern bank, held by the French, is low.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Albuera (very slow: 188K)

On the left centre of Beresford's position the road from Seville crosses the Albuera by a bridge and climbs the hills beyond. The village of Albuera is to the left of the road and a little back from the bridge. Below that point to the left the river was unfordable; the hills sank lower to the plain. Above the bridge, in front of the British right, the Albuera is shallow and the hills rise higber, but offered no definite point which could be held as marking the extremity of the right wing. Beresford thought his one assailable point was at the bridge, and here he bad concentrated his batteries, with Alten's division holding the village, and the 2nd divison under Stewart and the a division under Cole as a reserve. Blake's famine-wasted Spaniards held the extreme right, that being, in Beresford's erroneous judgment, least open to attack.

Soult's Plan

Soult's soldierly glance had quickly detected the weak feature in Beresford's line. In front of his right wing was a low wooded hill, behind which, as a screen, and within easy striking distance, might be gathered an overwhelming force.

Soult's plan was to fix Beresford's attention on the bridge by a feigned attack, then from the wooded ridge the 5th corps under Girard, and the cavalry under Latour Maubourg, with 30 guns, would leap on Beresford's right, brush aside the Spaniards, and seize the high broken tableland which there curved round it till it almost looked into the rear of Beresford's line. He could then cut off the British from their only line of retreat; and, caught between the French and the river, they must, as Soult triumphantly calculated, be destroyed or surrender.

With exquisite skill Soult, without visibly weakening his battle-line, actually gathered 15,000 men and 20 guns within leaping distance of Beresford's right. A general with such an unsuspected tempest about to break upon him from within musket-shot distance seemed predoomed to ruin.

At 9 o'clock a strong French column under Goudinot, with 10 guns, pouring out smoke and flame in their front, advanced to attack the bridge; a second column, under Werle, followed in support. Beresford in one point resembled Massena. He was hesitating in his tactics till the battle began, but he had the soldierly brain which grows clearer and keener in the roar of cannon. He noticed that the second French column did not push on in close support of the first.

As a matter of fact, as soon as the rising battle smoke had formed a sort of screen, it wheeled sharply to the left, and at the quick-step moved along the eastern bank of the Albuera towards the British right. Beresford at that moment guessed Soult's plan. His right was to be attacked; and he sent an aide-de-camp, riding at speed, to order Blake to wheel his battalions round at right angles to their present position, so as to check any attempt to turn the British position.

He despatched the second division to support Blake, and moved his horse-artillery and cavalry towards his threatened right. Blake, however, proved obstinate. His Spanish pride resented receiving orders from anybody; perhaps he doubted whether, if he attempted to change the position of his battalions, they would not dissolve in mere flight. Beresford came up in person to enforce his orders, and while the generals wrangled and the Spanish battalions had begun to wheel clumsily back, Soult's thunderbolt fell.

Girard's columns came swiftly across the stream and mounted the face of the hill. The French guns moved at the trot before them, halting every fifty yards to pour a tempest of iron on the shaken Spanish battalions, while Latour Maubourg's lancers and dragoons, galloping in a wider curve, threatened soon to break in on Blake's rear.

Beresford was, if not a great general, at least the most gallant of soldiers, and, with voice and gesture, he strove to send the Spaniards forward in a resolute charge against the French as they were deploying to turn his flank. Nothing, however, could persuade the Spaniards to advance. They stood their ground and fired hasty volleys into mere space, but would not -- perhaps they could not from sheer physical weakness -- charge.

Spaniards Run

In his wrath, Beresford, a man of great personal strength, seized a Spanish ensign with his flag, and ran him fiercely out through the smoke towards the quickly-moving French line. But the Spaniards would not follow, and the ensign, when released, simply ran back to his regiment, as a solitary sheep which had been cut off might rush back to the flock! Only thirty stormy and tumultuous minutes had passed since Soult's attack had been launched; but already two-thirds of the French army, in compact order of battle, were drawn at right angles across Beresford's front.

The Spaniards were in disorder. The French guns, steadily advancing, were scourging Blake's shaken line with grape, and Soult's cavalry, riding fast, were outflanking them.

Otway's Portuguese cavalry moved out so as to check the French cavalry from coming down to attack the village from the rear, and Stewart's division came swiftly up to support the broken Spaniards. The first brigade, under Colborne, consisted of the Buffs, the 66th, the 31st, and the 2nd battalion of the 48th. Stewart led the brigade in person. Colborne, a cool soldier, wished to deploy before ascending the ridge on whose crest the fight was raging but Stewart was of an impatient temper.

He knew how deadly the crisis was. The shouts of the French grew ever more triumphant, the flash of their guns gleamed ever closer; and Stewart took up his regiments in column of companies past the Spanish right, and made the battalions deploy into line successively as they came in front of the enemy. These were hasty and perilous tactics.

The scene was one of wildest confusion. A furious rainfall made the hillside slippery. The air was full of a dense fog made blacker with battle smoke. At that moment, through the fog, to the British right came the low thunder of galloping hoofs. The volume of sound grew deeper. The grey vapour sparkled with swiftly moving points of steel. Suddenly out of the fog broke, with bent heads and the tossing manes of horses, a far-stretching line of charging cavalry.

The English regiments, in a word, were caught in the very act of deploying, and over them, with exultant shouts, with thrust of lance and stroke of sword, the French cavalry swept. In less than five minutes, two-thirds of the brigade went down. The Buffs, the 66th, the 48th were practically trodden out of existence; six guns were captured.

A lancer charged Beresford as he sat, solitary and huge, with despair in his heart, amidst the tumult. Beresford put the lance aside with one hand, caught the adventurous Frenchman by the throat with the other, and dashed him to the ground. The 31st, handled more promptly, and perhaps reached by the French cavalry a little later, had fallen swiftly into square. It stood fast, a sort of red parallelogram outlined in steel and fire, and upon its steadfast faces the French horsemen rode in vain.

But this was all that survived of what ten minutes before had been a gallant brigade. D'Urban says that the disaster which befell Colborne's brigade arose not from its delay in deploying, but from Stewart's refusal of Colborne's request that the right wing of one regiment should be kept in column.

Anecdotes of Action

Many thrilling incidents are still told of this wild scene. The king's colour of the Buffs was defended by Lieutenant Latham with unsurpassed courage. A stroke of a French sabre almost divided his face, a second blow struck off his left arm and the hand which held the colour; he was thrust through with lances and trodden underneath the hoofs of the galloping horses, and left for dead. But as he lay on the ground, with his solitary hand he tore the colour from the pole and thrust it under his bleeding body, where it was found hidden after the fight was over.

An ensign named Thomas, only fifteen years old, carried the regimental colour of the Buffs when the torrent of lancers broke his regiment and the captain of his company was struck down.

This mere boy took command of the company, crying out, in shrill youthful treble, "Rally on me, men; I will be your pivot." The fluttering colour he held drew the French swordsmen down upon him in eager swarms; his youth for a moment moved the pity of even the fierce French horsemen; he was called upon to give up the colours. He refused and was slain, still clinging to the staff. Of that particular company of the Buffs only a sergeant and a single private survived.

At that moment the victory was in Soult's grasp. He missed it by mere over-caution. The fog, to which Colborne's brigade owed its ruin, yet lay thick on the hill, and Soult could not guess what lay behind that vaporous screen. So he hesitated to advance, and his hesitation gave time for Houghton's brigade to come up.

That brigade was now moving into the tumult of the fight. It consisted of the 29th, the 57th, and the first battalion of the 48th. Houghton led it, waving his hat; Stewart rode beside him. But this time, taught by bitter experience, he brought the brigade up in order of battle.

The 29th was the leading regiment; the Spaniards, who, in the distraction of the conflict, were firing on friends and foes alike, stood in its path, and, as they could not be brought to either cease firing on the advancing British or to move out of their way, the 29th swept them from their path with a rough volley, and so came into the fight, Houghton fell, pierced with bullets, in front of his own lines.

The French lancers caught through the fog a glimpse of the steadily moving bayonets of the 29th, and rode straight at them, but two companies wheeled promptly, and drove back the horsemen with quick and murderous blasts of musketry shot. A steep and narrow gully crossed the advance of the 29th, and checked its meditated rush with the bayonet on Girard's battalions. The other regiments of the brigade came into line with the 29th; the 3rd brigade, consisting of the 28th, the 34th, and the 39th, under Abercromby, also came into the fight.

The battle at this point offered the scene of a long thin line of British infantry, parted from the massive French columns by a steep gully, which forbade a close charge. Houghton's men, in fact, stood within a hundred paces of the enemy, firing by files from the right of companies. The roar of musketry volleys, delivered at little more than pistol-shot range, was incessant, the deeper bark. of the cannon swelled the tumult, as they poured showers of grape at short range across the gully on either side. Through the mist the French cavalry rode to and fro, slaying the survivors of the broken regiments at will, except where the still unbroken lines of the English drove them off with their steady fire.

The slaughter was great. Of the 57th alone, its Colonel, Inglis, 22 officers, and more than 400 men Out Of 57o had fallen. "Die hard, my men! die hard!" said Inglis; and the 57th have borne the name of "Die-hards" ever since. Duckworth of the 48th was slain; Stewart was wounded. It was plain that Houghton's brigade was perishing in that dreadful fire; it was only a question of minutes when it must cease to exist as a fighting force. The British ammunition, too, was failing.

In such a crisis, desperate counsels emerge. Beresford's best quality, his fighting courage, for a moment wavered. He resolved to retreat, and commenced to make preparations for falling back. He did not realise therein a rearward movement would cause; nor did he remember what resources yet remained to him. The battle was saved by the quickness and resource of Colonel Hardinge, who afterwards won fame in India, and who now brought up Cole with the 4th division into the fight, and the 3rd brigade of the 2nd division under Abercromby. Cole's brigade had started from Badajos at eleven the preceding night, and marching without halt, reached the scene of the fight just as the French lancers had executed their triumphant charge on Colborne's regiments.

The brigade had scarcely halted when Hardinge, riding up, urged Cole to advance. Cole's first brigade, consisting of two Fusilier regiments, the 7th and 23rd, under Meyers, marched straight up to the crest of the hill. Abercromby came up its left flank.

Crisis of the Battle

It was the crisis of the fight. The scanty wrecks of Houghton's regiments were beginning to fall back. Soult, at last, had pushed his whole reserves into the fight. The field was heaped with carcases. The French columns were advancing with a tempest of triumphant shouts. Then, through the fog, on the right of the groups which yet survived of Houghton's brigade, came in long and steady line Cole's Fusiliers. Abercromby's regiments at the same moment came round the flank of the hill.

In an instant the physiognomy of the battle was changed. Girard's massive column found itself smitten at once on front and flank with a crushing fire. The answering fire of the French was of course deadly, but it failed to stop the gallant Fusiliers.

One of the noblest passages in British prose literature is that in which Napier describes their onfall. Something of the tumult and passion of the battle, of the clash of steel, and of the roll of musketry volleys -- something, too, of the triumph of victory, still rings through its resonant syllables, and the oftenquoted sentences may be quoted once more:

- "Such a gallant line," says Napier, "arising from amid the

smoke, and rapidly separating itself from the confused and

broken multitude, startled the enemy's masses, which were

increasing and pressing forward as to assured victory; they

wavere ' d, hesitated, and then, vomiting forth a storm of fire,

hastily endeavoured to enlarge their front, while the fearful

discharge of grape from all their artillery whistled through the

British ranks. Myers was killed, Cole and the three colonels-

Ellis, Blackeney, and Hawhshawe -fell wounded, and the

Fusilier battalions, struck by the iron tempest, reeled and

staggered like sinking ships.

Suddenly and sternly recovering, they closed on their terrible enemies, and then was seen with what a strength and majesty the British soldier fights. In vain did, Soult, by voice and gesture, animate his Frenchmen; in vain did the hardiest veterans break from the crowded columns and. sacrifice their lives to gain time for the mass to open on such a fair field; in vain did the mass itself bear up, and, fiercely striving, fire indiscriminately on friends and foes, while the horsemen, hovering on the flanks, threatened to charge the advancing line.

Nothing could stop that astonishing infantry. No sudden burst of undisciplined valour, no nervous enthusiasm weakened the stability of their order ; their flashing eyes were bent on the dark columns in front, their measured tread shook the. ground, their dreadful volleys swept away the head of every formation, their deafening shouts overpowered the dissonant cries that broke from all parts of the tumultuous crowd as slowly, and with a horrid carnage, it was driven by the incessant vigour of the attack to the farthest edge of the hill.

In vain did the French reserves mix with the struggling multitude to sustain the fight; their efforts only increased the immediate confusion, and the mighty mass, breaking off like a loosened cliff, went headlong down the ascent. The rain flowed after in streams discoloured with blood, and 1800 unwounded men, the remnant of 6000 unconquerable British soldiers, stood triumphant on the fatal hill."

Beresford, it seems, though he praised Cole's advance in his despatch, privately regarded it as a blunder. It is disputed whether Hardinge ordered Cole in Beresford's name to advance, or only urged him, with more or less vehemence, to do it. Cole himself has decided the point as to whether Hardinge, in Napier's phrase, "boldly ordered General Cole to advance."

Hardinge himself said he only offered "urgent advice," but advice which "his position on Beresford's staff made semi-authoritative."

As a matter of fact, Hardinge was at Albuera an aide- de-camp of twenty-three or twenty-four. Cole had express orders from Beresford not to leave his position without special instructions, and Cole declares that it was his personal resolution, not Hardinge's advice, still less Hardinge's "orders," which made him take the great responsibility of advancing.

The Fusilier brigade consisted of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 7th, and the 1st battalion of the 23rd, 1500 rank and file. The cavalry tried to repeat on Cole's brigade their performance on Colborne's, and a battalion of the 7th at quarter distance formed square at every halt to cover the right wing of the Fusiliers.

The French cavalry charged; it is said, indeed, they actually broke the right of the Fusiliers, but were driven off by the stubborn courage of that regiment and by a volley from some Portuguese.

The fatal mistake on the French side was Girard's advance with the 5th corps in close column. The British, firing from a wide front, and firing coolly, completely crushed the head of the column. Girard tried to deploy to his right, but the fire of the English was too fierce, the space too contracted, the confusion in his own ranks too great.

The leading French regiment broke, having lost 600 men, and the other French regiments in turn gave way, scorched by the terrific fire poured on them, till the whole mass rolled in confusion down to the stream and beyond it.

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com