The strategy on which Wellington depended for

baffling the French rush on Portugal may be told almost in

a sentence. He had created a great natural fortress --

the far-famed lines of Torres Vedras -- which could be

held against the utmost strength of France. He would fall

back on this, wasting the country as he went, so that

Massena would find himself stopped by an impregnable

barrier, and in the midst of a wilderness where his great

army must starve. Meanwhile, on the rear and along the

communications of the enemy a tireless guerilla warfare

would be kindled. Massena, under these conditions, must

either retreat or perish.

The strategy on which Wellington depended for

baffling the French rush on Portugal may be told almost in

a sentence. He had created a great natural fortress --

the far-famed lines of Torres Vedras -- which could be

held against the utmost strength of France. He would fall

back on this, wasting the country as he went, so that

Massena would find himself stopped by an impregnable

barrier, and in the midst of a wilderness where his great

army must starve. Meanwhile, on the rear and along the

communications of the enemy a tireless guerilla warfare

would be kindled. Massena, under these conditions, must

either retreat or perish.

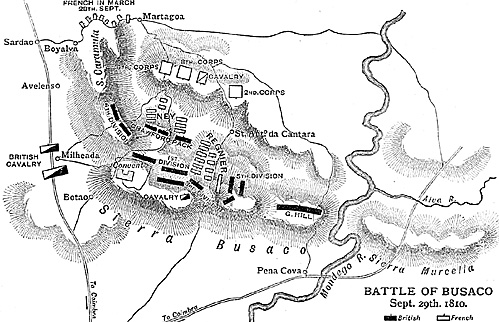

Jumbo Map of Battle of Busaco (very slow: 274K)

It was a great scheme, planned and executed with the highest genius. As a matter of fact, within the sweep of Wellington's great hill-fortress the liberty of Europe found its last shelter. And the moment when Massena fell sullenly back from the lines of Torres Vedras marks the decisive and fatal turn of the tide in Napoleon's fortunes.

Criticism of Wellington

But Wellington's designs were little understood either in England or by his own forces; and, at the very moment when he had shaped this great and triumphant strategy destined to achieve such memorable results, he was the subject everywhere of the despairing doubts of his friends, as well as the loud criticisms of his enemies, "It is probable," Lord Liverpool himself said, "the army will embark in September."

"Your chances of successful defence," he wrote to Wellington in March 1810, "are considered here by all persons, military as well as civil, so improbable, that I could not recommend any attempt at what may be called desperate resistance."

Wellington's own officers wrought great mischief by their indiscreetly uttered doubts. Wellington complained of this with a vigour which has all the effect of wit.

"As soon as an accident happens," he said, "every man who can write, and who has a friend who can read, sits down to give his account of what he does not know, and his comments on what he does not understand; and these are diligently circulated and exaggerated by the idle and malicious, of whom there are plenty in all armies."

When Wellington's friends in the English Cabinet, and the members of his own staff in Portugal, were of this temper, it may be imagined how loud and angry were the criticisms expended on the unfortunate general by his political enemies everywhere. The Opposition in the House of Commons moved for an inquiry into the conduct of the campaign. The Common Council of London, mistaking themselves for a body of military experts, solemnly accused Wellington, in an address to the King, of "ignorance," of "an incapacity for profiting by the lessons of experience," and of having exhibited in the Talavera campaign, (with equal rashness and ostentation, nothing but a useless valour." The spectacle of a group of London aldermen, newly charged with turtle-soup, rebuking the military "ignorance" of Wellington still has an exquisite relish of pure humour.

One orator in Parliament declared it to be "melancholy and alarming" that Wellington should have "the impertinence to think of defending Portugal with 50,000 men, of whom only 20,000 were English. "The only British soldiers left in the Peninsula before six months were over," this writer added, "would be prisoners of war" -- a singularly bad prophecy.

The attacks of English newspapers and the criticisms of English orators did not shake Wellington's steadfast temper, but they curiously deceived Napoleon. He was persuaded that he read the mind of England in the leading articles of the Opposition papers. He reprinted most of them, indeed, in the Moniteur for the consolation of French readers; and his belief that the English Cabinet must soon withdraw Wellington or itself be overthrown, made him regard the Spanish war as a trivial thing which could be safely neglected. So he left that conflagration unextinguished. He undertook the struggle with Russia while Spain was still unconquered, and thus made that fatal division in his forces which ultimately ruined him. The writers and orators attacking Wellington at this stage of the conflict did not in the least intend it, but, as a matter of fact, they rendered his plans a great service. They helped to keep Napoleon from coming himself to Spain!

Massena Marches

On September 15 Massena set his huge columns in movement, and began what he fondly hoped was his march to Lisbon. His troops carried seventeen days' rations; communications with Spain were abandoned, and Massena believed that within those days the campaign would be over.

Never was a more mistaken calculation made. Massena blundered at the outset in his choice of road, taking that along the right bank of the Mondego to Coinibra, fretted with every kind of difficulty. His Portuguese advisers had misled him. "There are certainly," said Wellington, "many bad roads in Portugal, but the enemy has taken decidedly the worst in the whole kingdom."

And into that worst of all Portuguese roads Massena poured cavalry, infantry, artillery, and baggage, in one vast and confused mass. Wellington fell steadily back, wasting the country as he went, and compelling the entire population to fall back with him. The clamour and discontent thus kindled may be guessed. Wellington's cool purpose was unshaken; but to steady the courage of the wavering, abate the too eager spirits of the French, and satisfy the temper of his own troops, growing angrily impatient of retreat, Wellington turned at bay at Busaco, and fought what was really a political battle.

Busaco is a wild and lofty ridge, stretching for a distance of eight miles across the valley of the Mondego, and thus barring Massena's advance. With its sullen gorges, its cloven crest, the deep, narrow valley running along its front -- a sort of natural ditch, so narrow that a cannon-shot spanned it, so deep and gloomy that the eye could not pierce its depthsBusaco was an ideal position for defence.

"If Massena attacks me here," said Wellington, "I shall beat him." The single defect of the position was its great size. Some portion of its rocky face or of its tree-clad heights must be left uncovered. The French van, indeed, came in sight of Busaco, and saw its ridge sparkling with bayonets, before the British were all in position, and Ney was keen for instant onfall.

But Massena was loitering ten miles in the rear; no attack could be made till he came up, and the opportunity was lost.

On September 27, the British troops watched from the steep ridge of Busaco the great French host coming on. It seemed like the march of a Persian army or the migration of a people. The roads, the valleys, the mountain slopes, the open forest intervals, glittered with steel, and were crowded, not merely with guns and battalions, but with flocks and waggons; while over the whole moving landscape slowly rose a drifting continent of dust.

Says Leith Hay: "In imposing appearance as to numerical strength, I have never seen anything comparable to that of the enemy's army from Busaco. It was not alone an army encamped before us, but a multitude. Cavalry, infantry, artillery, cars of the country, horses, tribes of mules with their attendants, sutlers, followers of every description, crowded the moving scene upon which Wellington and his army looked down."

It was nightfall before the human flood reached the point where the stern heights of Busaco arrested its flow. Then, in the darkness, innumerable camp-fires gleamed, and the two great armies slept.

It is always difficult to crystallise into lucid sentences the incidents of a great battle, and Busaco, if only by reason of the wide space of rugged and broken ground on which it was fought, easily lends itself to mistake. But the chief features of the battle are clear. Ney, with three divisions, was to attack the English left, held by Craufurd and the Light Division; Regnier, with two columns, was to fall on the English right, guarded by Picton and the third division "the Fighting Third." The two points of attack were three miles apart.

Regnier's Attack

Regnier's troops were a real corps d'elite, and included the 36th, a regiment specially honoured by Napoleon. It was still grey dawn, cold and bitter, with the mists clinging to the craggy shoulder of Busaco, and the stars shining faintly in the heavens, when Regnier put his columns in motion. French troops, well led, excel in attack.

At the quick-step, Regnier's gallant columns plunged into the ravine, and with order unbroken and speed unchecked, with loud beating of drums and fierce clamour of voices and sparkle of burnished steel, they swept up the face of the hill, their skirmishers running in an angry foam of smoke and flame before them.

The English guns tore long lanes through the dense French column; but though it left behind it a dreadful trail of wounded and dying, the charging column never paused.

The 88th, an Irish regiment of great fighting fame, waited grimly on the crest for their foes; but the contour of the hill, aided, perhaps, by the spectacle of that steadfast red line sparkling with steel on its summit, swung the great French column to the right. It broke, an angry human tidal wave, over the lower shoulder to the left of the 88th.

Four companies of the 45th hold that part of the ridge. From the dip in the hill came the shouts of contending men and swiftly succeeding blasts of musketry volleys. Wallace, the colonel of the 88th, sent one of his officers running to a point which commanded the scene to learn what was happening. The French, he reported, had seized a cluster of rocks on the crest, while, beyond, a heavy column was thrusting back the slender lines of the 45th.

Wallace delivered a brief address in soldierly vernacular to his men. "Now, Connaught Rangers," he said, "mind what you are going to do; and when I bring you face to face with those French rascals, drive then: down the hill. Push home to the muzzle." Then throwing his men into column, he took them at the double along the crest of the hill. The 45th, at that moment, was pouring quick and rolling volleys on the French, but the great column came on without pause It was evident that in another moment the the line of the 45th would be broken, and Wallace took his men into the fight at a run, striking the French column on its shoulder.

An officer of the 88th describes the scene: "Wallace threw him self from his horse, and placing himself at the head of the 45th and 88th, with Gwynne of the 45th on the one side of him, and Captain Seton of tb 88th at the other, ran forward at a charging pace into the midst of the terrible flame in his front. All was now confusion and uproar, smoke, fire, an bullets; officers and soldiers, French drummers an French drums knocked down in every direction. British, French, and Portuguese mixed together while in the midst of all was to be seen Wallace fighting like his ancestor of old at the head of his devoted followers, and calling out to soldiers to 'press forward!' It was a proud moment for Wallace and Gwynne when they saw their gallant comrades breaking down and trampling under their feet this splendid French division, composed of some of the best troops the world could boast of. The leading regiment, the 36th, one of Napoleon's favourite battalions, was nearly destroyed; upwards Of 200 soldiers and their old colonel, covered with orders, lay dead in a small space, and the face of the hill was strewn with dead and wounded."

Wallace, with fine soldiership, halted his men on the slope of the hill; and as he dressed his line, Wellington rode up and told the panting colonel of the 88th that he "had never seen a more gallant charge."

Wellington, with Beresford by his side, had seen, from an eminence near, the 88th running forward in their charge, a regiment attacking a column, and Beresford had expressed some uneasiness as to the result. Wellington was silent; but when Regnier's division went reeling down the hill, wrecked by the furious onslaught of the 88th, he tapped Beresford on the shoulder and said, "Well, Beresford, look at them now!"

Marbot says of the 88th that their first volley, delivered at fifteen paces, stretched more than 500 men on the ground.

At one point on the British right the French for a moment succeeded. The light companies of the 74th and the 8Sth were thrust back by Regnier's second column. Picton rallied the broken lines within sixty yards of the eagerly advancing French, and led them forward in a resolute charge, which thrust the French column down the slope; and, to quote a French account of their own experiences, "they found themselves driven in a heap down the steep descent up which they had climbed. The English lines followed them half-way down, firing volleys to which our own men could not reply-and-murderous they were."

Ney's Attack

Ney led the attack on the British left. Three huge columns broke out of the gloomy ravine and came swiftly up the steep face of the hill. From the crest above jets of flume and smoke shot out as the English guns opened on the advancing French. A fringe of pointed musketry flames sparkled along a wide stretch of the bill below the guns, where the Rifles were thrown out in skirmishing order. But the rest of the hill above seemed empty, and the French came on with all the fire of victory in their blood.

Neither the red flame of the artillery nor the venomous rifle-fire of the skirmishers could stay them. But on the reverse slope Craufurd held the 43rd and 52nd drawn, up in line ready for a great and surprising counter- stroke. On came the French columns. The flourished swords of the officers, the tall bearskin hats and sparkling bayonets of the leading files, were visible over the ridge. The skirmishers of the Rifles had been brushed aside like dust.

The French were already over the summit, a soldierly figure leading and vehemently calling them on. It was General Simon, and an English rifleman, falling back with fierce reluctance, suddenly turned and shot the unfortunate French general in the face, shattering it out of human resemblance.

At that moment Craufurd sent forward his two regiments, in a resolute counter-charge. Tradition has it, indeed, that Craufurd did not "send" the regiments forward; his fighting blood was kindled to flame, and he ran in advance of them toward the charging French, flourishing his sword and shouting to them, as if by way of taunt, "Avancez! Avancez!"

Column and line for a moment seemed to meet. Each man in the leading section of the French raised his musket and fired point-blank into the human wall coming forward at the double. A sudden gap in this moving red wall was for an instant visible, and two officers and ten men fell. Not a shot from a French musket had missed!

Then the long British line broke into a rending volley. Thrice, at a distance of not more than five yards, that dreadful blast of sound, with its accompanying tempest of flying lead, broke on the staggering French column. The human mass, in all its pride of glittering military array, seemed to shrivel under those fierce-darting points of flame. In tumult and dust, a broken mass, with arms abandoned, ranks torn asunder, and discipline forgotten, the unhappy column rolled down the steep face of Busaco, strewing its rocks with the dead and the dying.

One of the Napiers -- afterwards the conqueror of Scinde -- shared in that fight, and fell in it, shot cruelly through the face. "I could not die better," he gasped as the blood ran from his shattered mouth, than at such a moment."

George Napier gives a realistic sketch of the manner in which Ney's column was met and broken. "We were retired," he says, "a few yards from the brow of the hill, so that our line was concealed from the view of the enemy as they advanced up the heights, and our skirmishers fell back, keeping up a constant and well-directed running fire upon them; and the brigade of horse-artillery under Captain Hugh Ross threw such a heavy fire of shrapnel shells, and so quick, that their column, which consisted of about 8000 men, was put into a good deal of confusion, and lost great numbers -- before it arrived at a ledge of ground just under the brow of the hill, where they halted a few moments to take breath, the head of the column being exactly fronting my company, which was the right company of our brigade, and joining the left company of the 43rd, where my brother William was with his company. General Craufurd himself stood on the brow of the hill watching every movement of the attacking column, and when all our skirmishers had passed by and joined their respective corps, and the head of the enemy's column was within a very few yards of him, he turned round, came UP to the 52nd, and called out, 'Now, 52nd, revenge the death of Sir John Moore! Charge! charge! huzza!' and waving his hat in the air, he was answered by a shout that appalled the enemy, and in one instant the brow of the hill bristled with 2000 British bayonets. My company met the head of the French column, and immediately calling to my men to form column of sections, in order to give more force to our rush, we dashed forward; and as I was by this movement in front of my men a yard or two, a French soldier made a plunge at me with his bayonet, and at the same time his musket going off, I received the contents just under my hip and fell."

The struggle, Napier adds, occupied about twenty minutes; in that brief space of time this huge French column was driven from the top to the bottom of the mountain like a parcel of sheep. "I really did not think it possible," he says, "for such a column to be so completely destroyed in a few minutes as that was. When we got to the bottom, where a small stream ran between us and the enemy's position, by general consent we all mingled together searching for the wounded. During this cessation of fighting we spoke to each other as though we were the greatest friends, and without the least animosity or angry feeling."

The killed and wounded amongst Wellington's forces at Busaco amounted to 1200; but of the enemy 6000 fell.

Massena before the battle said, "I cannot persuade myself that Lord Wellington will risk the loss of a reputation by giving battle; but if he does I have him. Tomorrow we shall effect the conquest of Portugal, and in a few days I shall drown the leopard."

French generals, from Napoleon downwards, it is to be noted, were always going to "drown" or otherwise slay or put to flight the "Leopard." That mythical animal, however, as we have seen, had a surprising habit of surviving!

Marbot, with a frankness unusual in French literature, says of Busaco "it was one of the most terrible reverses which the French army ever suffered." In a sense the military results of Busaco are not great, but its moral effect was of the utmost importance. It proved the steadiness of the Portuguese soldier under British leadership. It showed that though Wellington, as a matter of strategy, was in retreat, he was strong enough to meet the French in frank battle and beat them, and Busaco gave a new and exultant confidence to public opinion, both in England and Portugal. Wellington himself summed up the result by saying, "It has removed an impression which began to be very general, that we intended to fight no more, but to retire to our ships; it has given the Portuguese a taste for an amusement to which they were not before accustomed, and which they would not have acquired if I had not put them in a very strong position."

Chapter XVII: The Lines of Torres Vedras

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com