On the night which followed the battle, the British

looked down from the heights they had so valiantly kept on

their foemen's camp. The whole country beneath them

glowed with countless fires, showing thousands of shadowy

forms of men and horses, mingled with piles of arms

glittering amidst the flames. There seemed all the promise

of a yet more bloody struggle on the following day.

Massena, indeed, at first meditated falling back on Spain,

and, as events turned out, it would have been a happy stroke

of generalship had he done so.

On the night which followed the battle, the British

looked down from the heights they had so valiantly kept on

their foemen's camp. The whole country beneath them

glowed with countless fires, showing thousands of shadowy

forms of men and horses, mingled with piles of arms

glittering amidst the flames. There seemed all the promise

of a yet more bloody struggle on the following day.

Massena, indeed, at first meditated falling back on Spain,

and, as events turned out, it would have been a happy stroke

of generalship had he done so.

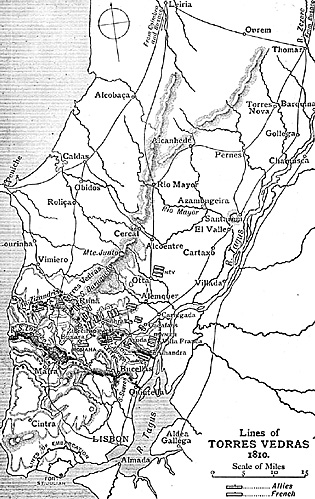

Jumbo Map of Torres Vedras (extremely slow: 407K)

All through the 28th he feigned to be making preparations for a new assault on the hill. Already, however, his cavalry were being pushed along a mountain path past the British left, and his infantry columns quickly followed. Massena was turning Wellington's flank, and bent on reaching Coimbra before him.

Wellington, out-marching his opponent, reached Coimbra first, and thence fell back towards Torres Vedras, pushing before him an immense multitude of the inhabitants of the district. He meant to leave nothing behind him but a desert. The French reached Coimbra on October 1, with the provisions intended to last them till they reached Lisbon already exhausted.

On October 4 Massena renewed his pursuit of Wellington. Then Trant, commanding an independent force of Portuguese, performed what Napier calls "the most daring and hardy enterprise executed by any partisan during the whole war."

He leaped upon Coimbra the third day after Massena had left it, captured the Frenchman's depots and hospitals, and took nearly 5000 prisoners, wounded and unwounded, amongst them a marine company of the Imperial Guards. And while Massena'ss tail, so to speak, was thus being roughly trampled on, his leading columns came in sight of the armed and frowning hills of Torres Vedras, an impregnable barrier behind which Wellington's army had vanished. Massena had not so much as heard of the existence of these famous lines until within two days' march of them!

The keen forecasting intellect of Wellington had planned these great defences more than a year before. A memorandum addressed to Colonel Fletcher, his chief engineer officer, dated October 20, 1809, almost exactly a year to a day before these great defences brought Massena's columns to a halt-gave minute orders for the construction of the lines. But the conception must have taken shape in Wellington's brain long before that date.

The Line

Lisbon stands at the tip of a long peninsula formed by the Atlantic on one flank and the Tagus, there a navigable river, on the other. Across this peninsula two successive lines of rugged hills -- the farthest only 27 miles from Lisbon -- stretch from the sea to the river. Wellington turned these into concentric lines of defence; with a third on the very tip of the peninsula, and intended to cover the actual embarkation of the British forces, if they were driven to that step. The outer line of the defence, a broken irregular curve of hills 29 miles in length, stretches from Alhandra on the Tagus to the mouth of the river Zizandre on the coast. The second line, some eight miles to the rear of the first, is 24 miles long, and reaches from Quintella on the Tagus to where the St. Lorenzo flows into the Atlantic.

These hills are pierced only by narrow ravines, and, with their tangled defiles and crescent-like formation, lent themselves readily to defensive works. The second line in Wellington's original plan was that which he intended to hold, the first line was merely to break the impact of Massena's rush. But under the incessant toil of the English engineers the defences of even the outer line became so formidable that Wellington determined to hold it, having the second line to fall back upon if necessary.

The lines of Torres Vedras were probably the most formidable known in the history of war. Two ranges of mountains were, in a word, wrought into a stupendous and impregnable citadel. In scale they were, says Napier, "more in keeping with ancient than modern military labours; " but they were constructed with a science unknown to ancient war.

Thus on the first line no less than 69 works of different descriptions, mounting 319 guns, had been erected. Across one ravine which pierced the range a loose stone wall 16 feet thick and 40 feet high was raised. A double line of abattis formed of full-grown oaks and chestnuts guarded another ravine. The crests of the hills were scarped for miles, yielding a perpendicular face impossible to be climbed.

Rivers were dammed, turning whole valleys into marshes; roads were broken up; bridges were mined. Rifle- trenches scored the flanks of the hills; batteries frowned from their crest. High over this mighty tangle of armed hills rose the summit of Soccorra. The lines, when completed, consisted of 152 distinct works, armed with 534 guns, providing accommodation for a garrison of 34,000 men.

Wellington's plan was to man the works themselves largely with Portuguese, keeping his English divisions in hand as a movable force, so as to crush the head of any French column if, perchance, it struggled through the murderous cross-fire of the batteries on the hills that guarded every ravine. Roads were made on the hill-crest, so that the troops could march quickly to any threatened point; and a line of signalstations, manned by sailors from the fleet, ran from hilltop to hilltop, so that a message could be transmitted from the Atlantic to the Tagus in seven minutes.

For more than a year these great works had been in course of construction. No less than 7000 peasants at one moment were at work upon them. The English engineers showed magnificent skill and energy in carrying out the design, and many soldiers who had technical knowledge were drawn from the British regiments and employed as overseers. So solidly were the works constructed, that many of them today, more than eighty years after the tide of battle broke and ebbed at their base, still stand, sharp-cut and solid. Wellington thus wrote in long-enduring characters the signature of his strong will and soldierly genius on the very hills of Portugal.

The scale and the scientific skill of these lines are perhaps less wonderful than the secrecy with which they were constructed. British newspapers were as indiscreet and British gossip as active then as now; French spies were as enterprising. And it seems incredible that works which turned a hundred square miles of hills into a vast natural fortress could have been carried out with the noiselessness of a dream, and with a secrecy as of magic.

Massena's Dilemma

But the fact remains, that not till Massena had reached Coimbra and was committed beyond recall to the march on Lisbon, did he learn the existence of the great barrier that made that march hopeless. Massena had trusted to the Portuguese officers on his staff for information as to the country he had to cross; but as they had accepted service under the French eagles, they naturally had never visited the district held by the British, and knew nothing of what the British were doing. When he turned fiercely upon his Portuguese officers, they urged this in self-excuse. But they had failed to warn Massena of the existence of the hills themselves. "Yes, Yes," said the angry French general. "Wellington built the works; but he did not make the mountains."

Massena spent three days in examining the front of Wellington's defences, and decided that a direct attack, with his present forces, was hopeless. But his stubborn, bear-like courage was roused, and he resolved to hold to his position in front of Wellington till reinforcements reached him.

It became a contest of endurance betwixt the two armies, a contest in which all the advantages were on the side of the British. Their rear was open to the sea; ample supplies flowed into their camps. The health of the men was good, their spirits high. They looked down from their hill-fortress and saw their foe facing a sullen warfare, with mere starvation. For six desperate and suffering weeks Massena stood before Wellington's lines. The French had raised plunder to a fine art; they could exist where other armies would starve. And Massena's savage and stubborn genius shone in such a position as that in which he now stood. He kept his men sternly in hand, maintained sleepless watch against the British, and sent out his foraging parties in ever greater scale and with ever wider sweep. To maintain thus, for six hungry and heroic weeks, 60,000 men and 20,000 horses in a country where a British brigade would have perished from mere famine in as many days, was a great feat.

Massena's secret lay in diligent, widespread, and microscopic plunder -- plunder raised to the dignity of a science, and practised with the skill of one of the fine arts; and Massena added the ruthlessness of an inquisitor to the skill of a great artist in robbery.

"All the military arrangements are useless," wrote Wellington, "if the French can find subsistence on the ground which they occupy." And Massena very nearly spoiled Wellington's plans by the endurance with which, in spite of famine and sickness, he held on to his position in front of the lines of Torres Vedras.

Skirmishes and Desertions

The long weeks of endurance were, of course, marked by perpetual conflicts betwixt the foraging parties and pickets of the two armies. A curiously interesting picture of this personal warfare is given in Tomkinson's "Diary of a Cavalry Officer."

The British cavalry patrols carried on a sort of predatory warfare with the enemy's parties on their own account. They looked on them as game to be hunted and captured; and the British private went into the business with characteristic relish, and performed really surprising feats. A sergeant and a couple of dragoons would bring in a "bag" of a score of French infantry with great pride.

On the other hand, there was a constant stream of desertions on both sides of the lines. That the French stole to the lines where they knew that at least food awaited them was not strange; but the British desertions were almost as numerous and much more mysterious.

Wellington himself was puzzled by it. "The British soldiers," he wrote to Lord Bathurst, "see the deserters from the enemy coming into their lines daily, all with the story of the unparalleled distresses which their army were suffering, and with the loss of all hope of success in their enterprise. They know at the same time that there is not an article of food or clothing which they need which is not provided for them; and that they have every prospect of success; yet they desert!"

In the French camp there was neither food nor hope; within the British lines there were both. Yet every night the astonished British officers had to report desertions. "The deserters," Wellington adds, "are principally Irishmen;" but they were not all Irishmen. The truth is, the average British private hates inaction. He is hungry for incident and movement. He found weeks spent in camp monotonous, and he deserted by way of variety.

The logic of starvation proved at last too strong for even Massena's stubborn courage, and on November 15 he fell back reluctantly to Santarem, having lost more than 6000 men, principally by starvation, in front of Torres Vedras. Wellington pushed out cautiously in pursuit, but at Santarem Massena turned grimly round on his pursuers.

He now held a strong position with supplies in his rear; and by holding Santarem he still seemed to threaten Lisbon, and so put a mask over the face of his own defeat. Wellington, on the other side, was not disposed to engage in active operations. The winter was bitter, the rivers flooded, the roads impassable.

And so the memorable campaign of 1810 came to an end with two great armies confronting each other, but neither Willing to strike. But all the honours and the substantial results of the campaign were with Wellington. Napoleon's confident strategy had gone to wreck on the lines of Torres Vedras.

Chapter XVIII: Massena's Failure

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com