Wellington, on landing at Lisbon, found at his disposal

a force of 26,000 men. Three French armies confronted

him. Soult to the north held Oporto with over 20,000 men,

which the junction of Ney and Mortier would bring up to

nearly 60,000. Victor, at Merida, to the west, stood ready

to move on Lisbon with a force of 24,000 men; betwixt the

two, and connecting them, stood Lapisse at Salamanca,

with 6000 men. Lapisse, however, presently marched

southward, and joined Victor, bringing that general's forces

up to 30,000 men. Lapisse's march simplified the problem

for Wellington.

Wellington, on landing at Lisbon, found at his disposal

a force of 26,000 men. Three French armies confronted

him. Soult to the north held Oporto with over 20,000 men,

which the junction of Ney and Mortier would bring up to

nearly 60,000. Victor, at Merida, to the west, stood ready

to move on Lisbon with a force of 24,000 men; betwixt the

two, and connecting them, stood Lapisse at Salamanca,

with 6000 men. Lapisse, however, presently marched

southward, and joined Victor, bringing that general's forces

up to 30,000 men. Lapisse's march simplified the problem

for Wellington.

He had now Soult to the north, and Victor to the west; both were to converge upon him and crush him. But Wellington held the interior position, and he could fall upon either force and destroy it before the other reached the field of action. Victor was eighteen marches distant, Soult practically less than five. He held the second city in Portugal and, acting on his policy of clearing Portugal of the French, and using it as a base of operations against the French power in Spain, Wellington resolved to advance against Soult.

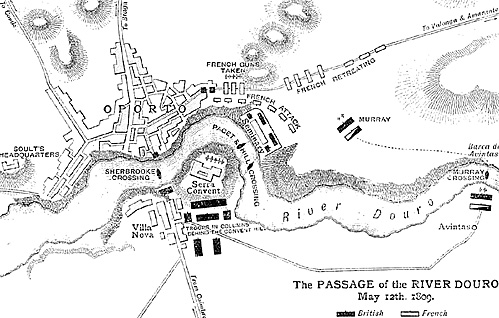

The British general moved swiftly. On May 2 he was at Coimbra with 25,000 men; on the 12th he was in sight of Oporto. Here was a great city, held by 20,000 French veterans, under Napoleon's ablest and most trusted marshal, and between Wellington and his foe rolled the Douro, a deep and swift river, 300 yards wide.

Soult, however, had been ill served by his outposts, and was in a curious state of ignorance as to Wellington's movements. He knew, indeed, that the Englishman was moving on Oporto, and he had drawn every boat to the French side of the river; but he did not know that his enemy was within striking distance. He expected, moreover, the English to make their appearance from the sea, and was eagerly watching the river seawards, at the very moment Wellington was preparing to cross the stream at his back.

The Douro

The Douro, immediately opposite the city, curved

sharply round a point on which stood what was called the

Serra Rock, crowned by a great convent. And at eight

o'clock on the morning of May 12, Wellington's troops

were drawn up in silent ranks under the screen of this rock.

Soult, uneasily doubtful as to the effects of Wellington's

stroke, was already despatching his heavy baggage by the

Valonga road, in case he had to abandon the city.

The Douro, immediately opposite the city, curved

sharply round a point on which stood what was called the

Serra Rock, crowned by a great convent. And at eight

o'clock on the morning of May 12, Wellington's troops

were drawn up in silent ranks under the screen of this rock.

Soult, uneasily doubtful as to the effects of Wellington's

stroke, was already despatching his heavy baggage by the

Valonga road, in case he had to abandon the city.

Jumbo Map of Passage of the Douro (very slow: 250K)

Wellington studied the situation with the stern, sure gaze of a great captain. Immediately opposite his position, on the French side of the river, stood a huge, isolated building called the Seminary.

On one side it touched the river, on the other it overlooked the Valonga road. Wellington despatched Murray with a brigade of infantry, the 14th Dragoons, and two guns, to cross the river by a ford, or by boats, three miles up its course; he secretly placed eighteen guns on the Serra Rock itself, so as to sweep the face of the Seminary on the other side of the river.

A barber, who little knew he was making history, had crossed the river from the city in a tiny boat. This was seized, and Colonel Waters, with a couple of companions, pulled coolly across the stream to the French side, discovered four good-sized boats stranded in the mud, and brought them back to the English bank.

It was now ten o'clock. So strangely careless was Soult, or so strangely mistaken, that he had not yet discovered Wellington's presence behind the Serra Rock. He had, indeed, been warned at six o'clock that morning of the British approach, but had sent no cavalry pickets out. As soon as the first boat Waters had secured reached the English bank, the fact was reported to Wellington. "Well, let the men cross," was his cool reply and 25 men of the Buffs stepped in the boat under an officer, quietly pulled across the river, and entered by a door in the Seminary walls. Never before was so audacious and perilous an enterprise begun in a fashion so cool!

The French sentries were apparently asleep, or were carelessly watching the long column of baggage rolling along the Valonga road. A second barge crossed, a third. Then suddenly, a tumult awoke in Oporto. French drums filled the air with their brazen rattle. The skirmishers came swarming down to the Seminary. The Buffs in that building, now under the command of Paget, opened an angry fire; the great battery on the Serra Rock was uncovered and swept the left front of the Seminary, so that no attack could be delivered against it on that face.

The French fire on the Seminary grew vehement; cannon added their deep bellow to the crackling musketry. But by this time other boats had been discovered, and the British were crossing in great numbers.

Paget had fallen wounded, and Hill was now in command in the Seminary.

Murray's column made its appearance on the French bank;

and Soult, who feared his retreat northward might be cut

off, abandoned the town.

Paget had fallen wounded, and Hill was now in command in the Seminary.

Murray's column made its appearance on the French bank;

and Soult, who feared his retreat northward might be cut

off, abandoned the town.

The English guns from the Serra smote his columns cruelly; they had, moreover, to pass under the Seminary wall, from which streamed a fire so deadly that five French guns were abandoned under its whip. Murray, curiously enough, allowed the broken and hurrying columns of the French to march past his front unharmed. They were so formidable in numbers, that he seemed to fear to attract their notice. Charles Stewart and Major Hervey, however, rode, with two squadrons of the 14th, into the mass of the French, captured General Laborde, and wrought great mischief. But it was a handful of dragoons charging an army, and the English horsemen were at last driven off with loss. But, at the expense of a little over 100 in killed and wounded, Wellington had crossed a river, broad and deep and swift, in the face of an enemy scarcely inferior to himself in numbers, and had driven Soult, with a loss of 500 men and five guns, in headlong retreat out of Oporto. It was a brilliant stroke of war.

And the leap upon Oporto was only a detail in Wellington's strategy. He had thrust forward Beresford, with his Anglo-Portuguese and a corps of Spaniards under Silvera, to seize the roads by which Soult must reach Amarante. Another force was marching to cut off his retreat into Galicia. Thus Soult was in sore straits. He had a victorious enemy both in his front and in his rear. The Douro was on his right; on his left was a wild and apparently trackless range of hills, the Sierra del Cathalina.

Soult, in this critical situation, showed the daring and the judgment of a great soldier. He abandoned his baggage and stores, destroyed his artillery, and by what were little better than goat-tracks, passed the mountains and gained Pombira, where he was joined by Loison's division. But Wellington was thundering closely and fiercely on his rear. To reach Braga, Soult had once more to take to the hills, destroying the guns and baggage of Loison's division. The guerillas vexed his flanks; the British threatened to outmarch him, and cut him off from his junction with Ney at Lugo. In wild tumult, the two armies, pursuers and pursued, pressed on.

Soult, in fact, in this fiercely urged retreat, endured more hardships and suffered incomparably greater military dishonour than Moore in his disastrous retreat to Corunna.

On May 18, Soult's hard-pressed columns reached Lorense. His soldiers were shoeless, ragged, without artillery or baggage; many of the troops, indeed, were without muskets. Only ten weeks before, Soult had marched from Lorense with a force which, counting the additional detachments which afterwards joined him, numbered 26,000 men and 58 guns. He was advancing on Lisbon to drive the English into the sea! Now his shattered columns came flying back as though driven by a whirlwind, leaving behind them all their guns and baggage, and more than 6000 men slain or captured!

It was clear that Wellington and his English could strike with sudden and shattering force. In what was practically a campaign of ten days, the English general had delivered Portugal, and driven the French army, under a famous Marshal, in reeling and ruinous defeat along the very roads which had witnessed the march of Moore's unhappy columns.

But there remained the more formidable task of dealing with Victor's force, and Wellington fell back on Oporto. Thence he marched at speed to Abrantes, where he halted to gather up his reinforcements and concert plans with Cuesta. In his brilliant campaign on the Douro his losses did not exceed 300 men, but sickness now raged in his camp. He had 4000 men in hospital. Only when 8000 new troops reached him from England did he move forward.

Wellington Enters Spain

On June 27 Wellington entered Spain with a force of 21,000 men and thirty guns. Cuesta's forces numbered 28,000, of the usual uncertain Spanish quality; while Cuesta himself, an old man, semi-imbecile, and cursed with all the obstinacy, and not quite the intelligence, of a Spanish mule, was an ally of the worst possible quality. And it was with such an ally Wellington was advancing against the marshals and armies of France!

The British general, it is to be noted, was curiously mistaken as to the strength of the French armies. The forces in front of him under Victor and Joseph exceeded 50,000 men. Soult, on his flank, had now been joined by Ney and Mortier, and formed a well-equipped force of 54,000 men. Wellington, to put it briefly, had committed himself, with Some 20,000 British and 38,000 Spanish troops, to a campaign in the narrow, entangled valley of the Tagus, barred at its western end by an army of 50,000 French veterans, while another army of 50,000 was gathering on his flank and rear. In the shock of actual battle, the Spaniards were practically to be counted out, but Wellington did not even yet quite realise this. He had not yet learned by experience of what obstinacy Spanish generals were capable, or of what cowardice Spanish troops. He ran an imminent risk of finding himself, with no other than his own 22,000 troops to rely upon, crushed between two French armies, numbering over 100,000 men.

At the very moment when, with numbers so inadequate, Wellington was facing risks so terrible, the English Cabinet, it is worth while remembering, had despatched one force of 12,000 men, under Sir John Stuart, to play at soldiering in Italy, and 40,000 magnificent troops to perish ingloriously of disease in the marshes at Walcheren! Wellington might easily have had 80,000 troops on the Tagus instead of less than 25,000. In that event who can doubt that all the succeeding campaigns of the Peninsula would have been unnecessary, and Waterloo itself might have been ante-dated by five years!

Wellington quickly began to realise the difficulties created by the almost incredible stubbornness of Cuesta and the equally unimaginable faithlessness of the Spanish juntas. Cuesta would neither march, nor halt, nor fight when his ally wished. He fell into semi-imbecile sleep in the midst of conferences with his brother general.

On July 22, Victor, with his single corps, lay within reach of the Anglo-Spanish army. It was agreed to attack him next day, but when Wellington wished to arrange the details, Cuesta went to bed. The British were under arms at three o'clock the next morning, but his staff dare not wake Cuesta till seven o'clock. Then that enterprising general drove up in a carriage drawn by six horses to the British headquarters, and -- according to one version -- announced that it was Sunday, and he had conscientious scruples against fighting on that day!

When, however, later in the day, the French began to retire, Cuesta consented to attack, and moved forward in his lumbering coach-and-six to examine the ground. Presently his coach halted, Cuesta sat down in the shade of a tree, and went peacefully and hopelessly to sleep again!

"If Cuesta had fought when I wanted him," said Wellington afterwards, "it would have been as great a battle as Waterloo, and would have cleared Spain of the French."

Wellington's difficulties, when linked to such an ally, may be guessed. But, in addition, his army ran an imminent risk of perishing from mere starvation. He had entered Spain with the most eager and solemn assurances from the Junta that provisionsall to be duly paid for in English gold-would be found for his troops.

But Spanish promises, as Wellington found, were worthless. Trusting to them was building on mere vapour. The two armies united on July 22; during the month which followed, the English troops received only ten days' bread, and an even smaller meat supply. Nearly 2000 horses perished for want of forage. The very offal of goats was eagerly bought in the British camp as food. Wellington could procure from the Spanish authorities smooth promises, plausible excuses, ingenious lies of every description, but no food; and this while Spanish magazines were full.

The British soldier has many virtues, but the capacity for accepting starvation with pensive resignation, and by the side of allies who are well fed, does not belong to him; and out of the experiences of British soldiers in their first joint campaign with the Spanish was bred a long-enduring anger, which bore some dreadful after results.

According to Napier, the excesses of British soldiers when Badajos and San Sebastian were stormed are explained by the anger bred of Spanish selfishness and neglect in the Talavera campaign.

Of Cuesta's obstinacy a single specimen may be given. Joseph and Victor had joined forces near Toledo, and now formed an army of over 50,000 men, which barred the march of Wellington and Cuesta on Madrid. Soult, with an equal force, was striking at their flank. It was necessary to fall back on some strong defensive position, where alone the Spaniards could sustain the shock of battle. But Cuesta refused to move. At Alcabon the French cavalry roughly charged some Spanish infantry, and the entire Spanish army was on the point of dissolving in mere flight. Night fell on a scene of wild confusion.

Wellington urged Cuesta in the strongest terms to fall back on Talavera while the English covered his retreat. But advice and exhortations were vain. That the British general urged any course was sufficient reason for Cuesta's refusing to adopt it.

On the next morning Wellington rode again to Cuesta's quarters, and pointed out to him that he was in a desperate position. The first shot fired would be the signal for his troops to dissolve. For himself, he was resolved to fall back. Cuesta met every suggestion with a mulish refusal. The British began their march, leaving the obstinate Spaniard to his fate; the French cavalry were in sight, coming quickly on. Then Cuesta yielded, but, says Napier, "addressing his staff with frantic pride, he boasted he had first made the Englishman go down on his knees!"

With his sure glance, Wellington had selected Talavera as the scene of what was to prove one of the most picturesque filghts, and well-nigh the most bloody, in the long roll of Peninsular battles. Talavera stands on the bank of the Tagus. Parallel to the Tagus, and at a distance of two and a half miles from it, was a mountain chain, with a deep ravine, a sort of huge natural ditch, at its foot.

A series of small hills, rounded and steep, stretches from t he riveralmost to the lip of this ravine, one hill, bolder and more rugged than the rest, standing like an outpost about half a mile from it. Wellington made this line of hills his position. It barred the whole valley of the Tagus against the French. The Spaniards formed his right wing. Their front was covered by deep ditches, a convent, a tangle of breastworks, &c., and was practically unassailable. Campbell's division in two lines came next the Spaniards; Sherbrook's division -- the Guards and the Germans -- stood next; Hill's division formed the extreme British left, and reached the edge of the deep ravine betwixt the mountain range and the rounded hills. By some oversight the terminal hill itself was not at first occupied by the British, and around it eddied the chief fury of the great battle.

Chapter XIII: Battle of Talavera

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com