The story of Talavera is crowded with dramatic and

stirring incident, and few battles have ever been waged with

sterner courage or more dreadful slaughter. Writing six

months after the fight, Wellington himself, who never

strayed into idle superlatives, wrote: "The battle of

Talavera was the hardest-fought of modern times. The fire

at Assaye was heavier while it lasted, but the battle of

Talavera lasted for two days and a night!"

The story of Talavera is crowded with dramatic and

stirring incident, and few battles have ever been waged with

sterner courage or more dreadful slaughter. Writing six

months after the fight, Wellington himself, who never

strayed into idle superlatives, wrote: "The battle of

Talavera was the hardest-fought of modern times. The fire

at Assaye was heavier while it lasted, but the battle of

Talavera lasted for two days and a night!"

The great tactical feature of the fight was the circumstance that, practically, the Spaniards took no part in it. Their single contribution was an attempt to effect a general stampede!

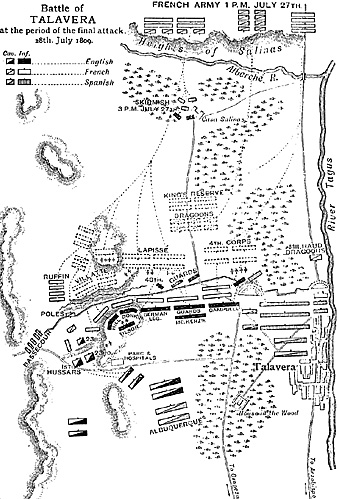

Jumbo Map of Battle of Talavera (very slow: 361K)

It is idle to deny the quality of courage to the Spaniards. Spanish infantry under Alva's iron discipline was once the terror of Europe. But throughout the struggle in the Peninsula Spanish valour was of an eccentric quality. It came and went in spasms. At Talavera it was a vanishing quantity. The Spanish regiments stood behind their almost impregnable position and watched, no doubt with keen interest, but without much active participation, the swaying fortunes of the battle betwixt the English and the French.

Hill, the most just-minded of men, says that at Talavera "there really appeared something like a mutual agreement between the French and the Spaniards not to molest each other!" But this practically resolved the fight into a struggle between Some 21,000 British and German troops with thirty guns, as against 55,000 French veterans with eighty guns.

The feature of the French tactics, and perhaps the secret of their failure, was the unrelated and scattered character of the attacks. they delivered. At three o'clock On July 27, the foremost French battalions came upon the outposts of the British left. The 87th and 88th, who formed these outposts, consisted of young soldiers, who were clumsily handled, fired in the confusion upon each other, and were sadly shaken.

Wellington himself, in the tumult of the fight, was well-nigh made a prisoner. The 45th, "a stubborn old regiment," with the 60th Rifles, checked the eager French, and the British fell sullenly back, with a loss of 400 men. Colonel Donkin with his brigade now occupied the hill on the extreme British left.

At this stage of the fight the French light cavalry rode forward on that part of the line held by the Spanish, and began a pistol skirmish, with a view of discovering Cuesta's formation. The Spaniards were nerve-sbaken. They fired one farheard and terrific volley into space, and then before its sound bad died away, no less than 10,000 of them, or nearly a third of Cuesta's entire force, betook themselves to flight! The infantry flung away their muskets, the gunners cut their traces and galloped off on their horses; baggage carts and ammunition waggons swelled the torrent of fugitives. One- third of Wellington's battle line seemed tumbling, at the crack of a few French pistols, into mere ruin!

The Spanish adjutant-general led the fugitives; Cuesta himself, in his carriage drawn by nine mules, brought up their rear. The unexaggerative Wellington says these flying Spaniards were "frightened only by the noise of their own fire. Their officers went with them."

It may be added that in all their terror these breathlessly flying Spaniards retained composure enough to plunder the baggage of the British army as they fled to the rear, while its British owners were fighting and dying for Spain at the front!

The spectacle of 10,000 infantry all running away at once might well have shaken the composure of any general; but Wellington launched some squadrons of English cavalry on the advancing French; such of the Spaniards as still hold their position opened a brisk fire, and the French in their turn fell back. Cuesta, by this time fallen into a paroxysm of rage, sent his cavalry at a gallop to head the fugitives and drive them back to their position. Some 6000 Spanish infantry, however, had run too fast and too far to be recalled.

Victor's Dash

Meanwhile Victor, who knew the ground well and was of an impatient spirit, saw that the hill on the British left was weakly occupied and was the key of the whole position, and resolved to make a dash at it. The French came on at the quick-step, and stormed up the steep slope with magnificent courage. Ruffin's division led. Villatte's was in support.

The British fought stubbornly, but the French were not to be denied, and their numbers were so great that they swept round the flank of the British regiments and seized the summit. Hill was in command of this part of the line, and a curious incident marked the beginning of the struggle.

As Hill tells the story, he was standing by Colonel Donnellan of the 48th, when in the dusk he saw some men come over the hilltop and begin to fire at them. "I had no idea," says Hill, "the enemy were so near."

I said to Donnellan, 'I was sure it was the old Buffs, as usual, making some blunder.'"

Hill rode off to stop the firing, and found that he had ridden into a French regiment! His aide-de-camp, Fordyce, was shot, Hill's own bridle was seized by a French soldier. But breaking roughly loose, Hill galloped down the slope of the hill, and brought up the 29th to support the 48th.

The 29th came on coolly, but with great resolution. The French were before them in the dusk, a black and solid mass, from which came a tempest of shouts. The 29th went forward till almost at bayonet-touch with the enemy, and then delivered a murderous volley. The sudden flash of the muskets lit up the faces of the French soldiers and their gleaming arms, and the long line seemed to crumble under that fierce blast of musketry fire.

Then with a triumphant shout the, 29th drove the French down the hill-slope by actual bayonet-push. The gallant Frenchmen came on again and yet again. The hill rose in the darkness a black and vaguely defined mass. But those who watched the fight from the distance could see sparkling high in the air on the hill slope the two waving lines of incessantly darting flashes, that now seemed to approach each other, and then drew farther apart; now crept higher in the darkness, and then sank lower.

Towards midnight the battle died away; but in that stubborn contest often waged hand to hand -- the British lost 800 men, the French 1000.

Next Day's Attack

During the night Wellington brought some guns to this hill, realising that the fate of the battle hung on its possession. Victor, on the other hand, grown only more obstinate from failure, persuaded Joseph to allow him to make a fresh attack in the morning. All night from the hill the listening English heard the rumble of guns in front of them. Victor was posting all his artillery on the hill opposite that held by his foe, so as to sweep its flanks and crest with a heavy fire.

In the early dawn a single gun boomed sullenly from the French lines. It was the signal. The battle instantly reawoke. The French battalions dashed from the shelter of the trees in the valley, and swarmed up the front and flanks of the hill, while twenty-two guns scourged with fire its crest. The 29th were lying down in line, slightly below the summit; Wellington himself stood by the colors of the regiment, watching the eagerly ascending French.

Just as the French infantry reached the crest, and their own guns necessarily ceased firing, the 29th leaped up, a long, steady line, curving with the shape of the hill; their muskets fell to the level, and a dreadful and rolling volley rang out. Then with a shout, the right wing of the 29th and the entire battalion of the 48th flung themselves on the French, and drove them with fierce bayonet-thrusts down the hill into a muddy stream at its base, whose sluggish current was choked by the bodies of the slain and reddened with their blood.

But on either flank of the hill the French were eagerly climbing. The English officers restored their line, and charged the French again and yet again, driving them down the slope. Still the Frenchmen, re-forming their columns, came on as gallantly as ever. Hill himself reckoned that the position was assailed by two French divisions, numbering not less than 7000 each. The stubborn English, however, though outnumbered overwhelmingly, clung to the hill.

Time after time, some officer, with bared head and brandished sword, gallantly leading a cluster of the 29th or of the 48th, would run forward and drive back the French in their immediate front. The British fell fast, Hill himself was wounded. At last the French, their fierce energy outworn, gave way. They had lost in forty minutes' desperate fighting more than 1500 men; their formation seemed to crumble; their shaken battalions ebbed in confusion down the hill.

Then followed nearly three hours' curious pause in the battle. The French generals were in council. Jourdan, Joseph's military adviser, urged that the French should fall back, and wait till Soult made himself felt on Wellington's communications. The. British must then retreat, and then would come the French opportunity. Even if Ney had not yet come up from Astorga with his corps, Soult with 40,000 men could be at Placencia by July 30, ready to strike at Wellington's line of retreat. To fight on the 28th or 29th was to throw away a great strategical advantage.

But Joseph was trembling for his capital. Victor was sore with defeat; his blood was heated with the fight. He urged that the fatal hill should be attacked a third time, and that Sebastiani should assault the British centre and right at the same time. If that combination failed, he said, they might give up making war!

Wellington, during this pause in the fight, sat on the summit of the fiercely contested hill, watching the French lines. Donkin came up to him as he sat, with an alarming message, sent in by Albuquerque, who was in command of the Spanish cavalry. Cuesta, the warning ran, was "betraying" his ally. Wellington listened to the message with imperturbable coolness.

"Very well," he answered; "you may return to your brigade!" What Cuesta might, or might not, do could not shake the British general's iron coolness, Perhaps he thought no "betrayal" could be more mischievous than Cuesta's "assistance!"

Meanwhile, a sort of "truce of God" was established betwixt the rank and file of the two armies. They were parched with thirst, and the rivulet at the foot of the hill beckoned them. The men crowded on each side to the water's edge; they threw aside their caps and muskets, and chatted to each other in broken French, and still more fragmentary English, across the stream. Flasks were exchanged, hands shaken. Then the bugle or the rolling drum called the men back to their colours, and the fight awoke once more.

Eighty guns broke into fire from the French lines. On the French left a great column, like some broad, majestic human river, edged with glittering steel, flowed out of the wood, surged swiftly forward, and broke in a sort of spray of flame on the British centre. This was held by Campbell's division, with Mackenzie's brigade in support. The regiments there had watched the long fight on the British left till their temper had risen to something like fury.

They broke into loud shouts as the French came on, the shout that moved Turenne's admiring wonder when he first saw English soldiers move into battlemet their foes with fiery courage, crumpled up their front, scourged their flanks with angry volleys, and drove them back in confusion with the loss of ten guns.

New Attack

A new attack on the British left was meanwhile being organised. Villatte's division, with two regiments of light cavalry in support, was crossing the British front to join in the attack, and Wellington sent at them Anson's cavalry brigade, consisting of the 23rd Light Dragoons and the 1st German Hussars. Gallantly rode the two regiments. The ground seemed level before them; their enemy was in clear sight. The British infantry regiments cheered the horsemen as they swept past. Several lengths in front of the 23rd, Colonel Elley, conspicuous from the colour of his horse, a beautiful grey, led.

Suddenly it was discovered that in the low brushwood through which the cavalry were now galloping, gaped a sharp and deep ravine. Elley reached it first, going at speed; to check his horse or turn was impossible. He rode straight at the great ditch. His gallant horse leapt it; then Elley turned with a warning gesture to check his men. But the galloping line was now on the edge of the ravine. Some leaped it; some tumbled into it; others scrambled through it and over it. And broken thus into clusters, the horsemen dashed at the French squares, rode through their fire, flung themselves furiously on the French light cavalry beyond, and shattered them with their charge.

The Germans reached the edge of the fatal ravine a few moments later than the British. The accepted tradition is that their Colonel, Arentschild, a warwise veteran, reined in on the brink of the ditch, saying, " I will not kill my young mans," while the hotter-blooded 23rd crashed through the ravine and rode on to attack an army in position. The "History of the King's German Legion," however, refutes that story. The ravine in front of the hussars, it says, was from six to eight feet deep and from twelve to eighteen feet wide, and the Germans rode at it as resolutely as the dragoons themselves, but with not quite the same speed, and having crossed, they did not expend themselves in attempting an impossible feat. The fiery English dragoons were by this time racing past the front of the French squares upon the brigade of chasseurs in their rear, which, as we have seen, they broke. But, in turn, they were assailed by a regiment of Polish lancers, and only scattered groups reached the British line again.

It was a mad charge, as heroic as Balaclava. Out of a little over 400 dragoons, no less than 207 men and officers were left on the field; of the German hussars, only thirty-seven fell, and these figures show how unequal were the risks dared by the two regiments. The dragoons had joined just three weeks before, and the morning after the battle they could only assemble 100 men on parade. But the charge was not wasted. It arrested the march of Villatte's division, and prevented it joining the attack on the British left.

The attack on that hill was raging afresh by this time, but with no better success than at first. In the British contre, however, the French gained an advantage, which, for a moment, seemed fatal. Lapisse fell with great resolution on Sherbrook's division, his attack being heralded by a dreadful artillery fire. The Guards met the French eagerly, broke them, tumbled them back, and pushed fiercely on their rear.

There was no holding the Guards in hand. They pushed recklessly on, themselves disordered with the ardour of their advance, till, suddenly, on front and flank, the French batteries opened on them an overpowering fire. The broken Guards reeled; the French reserves came eagerly into the fight. The Guards, as they fell back, jostled roughly on the Germans in support, shook their formation, and, for a moment, the British centre was completely broken. No less than 500 of the Guards had fallen.

It was the critical moment of the fight; and then it was seen for how much, in war, a great general counts.

Wellington had watched the too eager pursuit of the Guards; he knew what would surely follow, and while the Guards were still in the rapture of their onfall, he had set the 29th in movement from the hill they had held so long, to cover the gap in the centre made by the too rash advance of Sherbrook's men.

At the last moment, Wellington halted the wasted and scanty lines of the 29th, and took forward the 48th instead. That famous regiment came up, a long and steady line, as the Guards and Germans were being driven back in tumult and disorder. The 48th wheeled steadily back by companies, and let the broken mass sweep past them; then falling swiftly into line again, they moved forward, pouring on the French swift and repeated volleys, while the Guards and Germans instantly rallied behind them. Lapisse himself had fallen, mortally wounded, and his column drew sullenly back. The great fight was over.

If we omit the fighting on the 27th, the struggle on the 28th may be condensed into Napier's terse sentences: "30,000 French infantry vainly strove for hours to force 16,000 British soldiers, who were, for the most part, so recently drafted from the militia that many of them still bore the distinctions of that force on their accoutrements."

And they failed. The slaughter was cruel. The British lost in killed and wounded, 6200 men and officers -- not far short of one-third of their whole number. The loss of the French reached 7400. The Spanish claimed to have lost 1200 in killed and wounded, but these figures included the losses of the 26th and 27th, and even then were doubtful. Cuesta, indeed, had arranged on the 29th to shoot sixty officers and 400 men of his own troops for the crime of running away the previous day. With great trouble Wellington persuaded him to be content with shooting six officers and forty men, by way of encouraging the others.

End of Battle

As night fell, the grass on the slopes of the hills where the battle had raged took fire. It was long, dense, and very dry; the red flames ran, a broad front of dancing fire, over the fields where the dead and wounded lay thickly. The British were utterly exhausted. The men were without food; they had borne the strain of battle for many hours.

In the middle of the fight, indeed, a soldier addressed Wellington himself, and said, "It was very hard they had nothing to eat," and asked they might be allowed to go down and fight, "for when they were fighting they forgot their hunger!"

But when the fight was over, hunger awoke again with cruel keenness. At nine o'clock on the morning after the battle, for example, the 29th, with waving colours but with wasted lines, marched slowly down from the hill they had hold. They had practically fought on that rough summit for two days, and it was strewn with the bodies of 186 officers and men from its ranks.

But just at that hour, Craufurd's Light Division, consisting of the 43rd, 52nd, and 95th regiments, marched into the British camp. In twenty-six hours these three regiments had covered sixty-two miles, under an almost intolerable sun, each man carrying from fifty to sixty pounds weight on his back. And in that amazing march only seventeen men fell out of the ranks! They met thousands of Spanish fugitives on the road, and were told incessantly that the English were defeated and Wellington slain. Yet, without pause or break, these gallant regiments pressed on to join their comrades, and reached the scene *of the battle in perfect fighting order.

Each soldier, it must be remembered, carried a musket, 80 rounds of ammunition, a greatcoat, a blanket, a knapsack, with kit, canteen, haversack, bayonet, &c. ; a load which, over a distance so great and in a time so short, might have taxed the carrying capacity of a horse. Many of the men, it is to be added, were faint with hunger; all endured extreme anguish from thirst and heat.

Much controversial ink has been shed as to the exact facts of this famous march, but the truth seems to be at last proved beyond reasonable doubt. The march was made practically in two sections. A march of twenty-four miles ended at Oropeso on the forenoon of July 28, having been completed before the news of battle reached the regiments. When the tidings came, they immediately. resumed their march, pressed on, with a brief halt, all-night, and reached Talavera before noon on the 29th. They were short of food and water; the heat was excessive; the men were heavily burdened, yet they covered sixty-two miles in twenty-six hours.

French rhetoric turned Talavera into a victory for the French arms. A bulletin was issued announcing that the English had been cut up and destroyed. But Napoleon had written too many bulletins to believe one of them- especially one written in French.

"Truth," he wrote indignantly to Joseph, "is due to me!" -- whatever economy of truth might be practised in the case of others. He had Wellington's and Joseph's accounts of the battle, and he implicitly believed the English version. Wellington said he had captured so many guns; Joseph denied the French had lost any; and Napoleon told Joseph bluntly he believed Wellington. Victor himself declared to an English officer taken prisoner, that, much as he had heard of the fighting quality of the British soldier, he could not have believed that any men could have been led to attacks so desperate as some he had witnessed made by the British at Talavera.

Chapter XIV: Massena and Wellington

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com