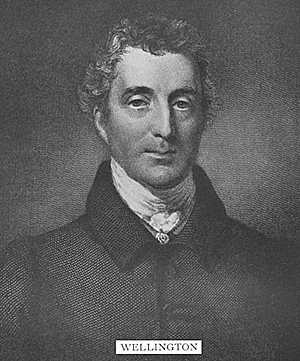

Every one is familiar with Wellesley's -- or rather, to

give him henceforth the more famous and familiar name --

with Wellington's appearance at this stage of his career:

the medium-sized figure, with its air of erect alertness; the

black hair sprinkled with grey, though he was not yet forty;

the steadfast eyes, the firm mouth, the high-bridged hawk-like nose.

Every one is familiar with Wellesley's -- or rather, to

give him henceforth the more famous and familiar name --

with Wellington's appearance at this stage of his career:

the medium-sized figure, with its air of erect alertness; the

black hair sprinkled with grey, though he was not yet forty;

the steadfast eyes, the firm mouth, the high-bridged hawk-like nose.

Wellington's face was not beautiful, not even very intellectual, nor specially that of a soldier. The straight line from the temple to the curve of the jaw, it is true, gave a look of severe grace to one angle of his countenance. His sunken cheeks he owed to the loss of his teeth, and his scorn of the dentist's art.

But, as studied in any familiar picture, the forehead is low, the features curiously immobile, while the firm thin lips shut like the lid of an iron chest. It is not a generous face; no curve in it is suggestive of sympathy, But there is in it a curious look of calm strength; while the clear hard lines, the falcon-like nose, the curving solid under-jaw, give-exactly as the cutwater of a clipper ship does -- an overwhelming impression of swiftness and strength. It is the face of a man who would cut his way through difficulties as a steel plane, with the energy of steam behind it, cuts its way through wood; and with no more feeling than a steel plane! No one will suspect Wellington of humour, yet Rogers, in his "Recollections," credits him with an almost unsuspected gaiety of mind.

"His laugh," he says, "is easily excited, and it is very loud and long, like the whoop of a whooping cough often repeated." His very mirth, that is, was the mirth of a hard nature.

Wellington had visible and great limitations. It would be unjust to say that he had no sympathy. It is not merely that, according to one tradition, he wept as he saw the dead bodies lying thick on the breach at Badajos; or that he wept again -- reluctant iron tears -- as he heard the roll-call, sad as a hundred dirges, of the slain at Waterloo. Did not an astonished House of Lords see him weep when he had to announce the death of Peel? But the fountain of either tears or sympathy in Wellington lay very deep, and was not easily reached. He had the reserve of an aristocrat, the shy and awkward pride of his race, that made the expression of emotion hateful to him. Blunt, cool, and dry, sparing of praise, quick to censure, he could inspire confidence, but not enthusiasm, still less love.

Yet, for military purposes, the confidence Wellington kindled in the rank and file of his army was better, perhaps, than either enthusiasm or love. His soldiers were sure their blood would not be idly shed. Their general would make no blunders. Nobody could outwit him. He would never fail ill resource: He would neglect nothing. "That long-nosed beggar that beats the French," was the phrase his soldiers used to describe him.

After the bloody struggle of Albuera, Wellington visited the hospital at Elvas, crowded with the wounded of the 29th regiment. "Well, old 29th," he said, "I'm sorry to see so many of you here."

"There would have been fewer of us here if you had been with us!" was the reply. That confidence on the part of his soldiers was worth more to Wellington as a general than great reinforcements.

Wellington certainly lacked imagination. His intellect had not the range, the glow, the wizard gleam, the lightning-like swiftness of Napoleon. Yet he had great compensating qualities. There was the clearness as well as the hardness of a crystal in his intellect. If his imagination lacked wings and never left the solid earth, yet it was, within a narrow area, strangely luminous and keen, and was always harnessed to practical uses.

When, as a youth of eighteen, he received his commission as ensign in the 41st regiment, almost his first act was to cause a private soldier to be weighed, first in full marching order, with arms and accoutrements, and afterwards without them. He wanted to find out what the soldier actually had to carry. To some one, long afterwards, who expressed his surprise at the incident, he replied, "Why, I was not so young as not to know that, since I had undertaken a profession, I had better endeavour to understand it."

That incident expresses perfectly one feature of Wellington's genius, its grasp of the practical conditions of war, its piercing insight into detail.

Lord Roberts, no mean judge, says that Wellington has been "underrated as a general, and overrated as a man;" and there is no doubt that Wellington's failure as a politician has long served to obscure his magnificent qualities as a soldier. Some one told him once of Lannes' definition of a great general.

"The greatest general," said Lannes, "is he who hears more quickly in the thunder, and sees more clearly in the smoke of battle than at other times."

Wellington agreed. The highest quality in a general was coolness. "The perfection of practical war," he said, "was to move troops as steadily and coolly on a field of battle as on parade."

"Only," added Wellington, "the mind, besides being cool, must have the art of knowing what is to be done and how to do it." That sentence exactly expresses his own genius for war. His brain in the tumult and distraction of a great battle had the coolness as well as the clarity of an ice- crystal. With all human passions at their highest point on every side of him, Wellington rode impassive; and his blunt, unexaggerated, and homely speech, with no strain of anything exalted in it, has the most curious effect when heard amid the roar of, say, Salamanca or Waterloo. He never talked of glory.

If he had fought a battle under the shadow of the Pyramids, it would never have occurred to him that forty centuries from their summit were contemplating the performance; and he certainly would not have introduced those forty astonished centuries to the British private, or even to his British generals.

At Guinaldo in 1811, Wellington was playing a desperate game of bluff, holding his ground with two weak divisions within reach of Marmont's army, 60,000 strong. He did this to give Craufurd time to fall back. Wellington carried an unclouded face, while his staff was in a mood of great agitation. You seem quite at your case," said Alava to him. "Why, it's enough to put a man in a fever!"

"I have done according to the very best of my judgme nt all that can be done," said Wellington. "Therefore I care not either for the enemy in the front or for anything they may say at home."

Sir William Erskine tells the story of how one morning, in a dense fog, a British division got separated from the rest of the army, Wellington being with it. Some prisoners were brought in, and then it was learnt that the entire French army was in their immediate front. If the fog lifted they were lost. Every one was disturbed; but all that Wellington said was, in the coolest tones, "Oh, they are all there, are they? Well, we must mind a little what we are about, then!"

A hundred stories must be told illustrative of Wellington's cool, blunt, and, so to speak, unbuttoned habit of speech when in the very crisis of a great battle. And he had pre-eminently the art of "knowing what was to be done and how to do it." He was unsurpassed, that is, in executive genius. Industry, method, simplicity, directness, all in the highest degree, these were the characteristics of his intellect. "Wellington," says Lanfrey, "dazzled no one-but he beat us!"

Napoleon's marshals, Wellington once said, "plan their campaigns just as you might make a splendid set of harness. It looks very well, and answers very well, till it gets broken, and then you are done for! Now I made my campaigns of ropes; if anything went wrong, I tied a knot and went on."

The secret of his success, Wellington explained again, lay in "the application of good sense to the circumstances of the moment."

In another mood he attributed his success to "always being a quarter of an hour earlier than he was expected."

"What is the test of a great general?" Wellington was once asked,. "To know when to retreat and to dare to do it," was his reply.

Wellington, though there were some unlovely aspects to his character, had noble moral qualities. Superlatives are the natural language of poetry, and Tennyson's resonant and magnificent " Ode " sings notes too high even for Wellington. He was not quite "the last great Englishman," nor was life for him a "long self- sacrifice."

In his earlier years, at all events, Wellington had a keen ambition, and a quite adequate sense of his own merits. But ambition in him cooled as it was rewarded, instead of growing, after the usual human fashion, yet more hungry.

"Truth-lover was our English Duke," says Tennyson, and that is the simplest statement of fact. No other great character in history, perhaps, ever used speech more simply, or had so obstinate a habit of telling the truth, or a more healthy contempt for lying and liars. It is amusing, indeed, to find that Muffling in 1815, when appointed to represent the Prussian army on Wellington's staff, was solemnly warned by Gneisenau against Wellington's incorrigible habit of lying! By his relations with India and his transactions with the nabobs, Gneisenau told Muffling, Wellington had become so accustomed to duplicity that he was "a master in the art, and able to outwit the nabobs themselves."

After marching and camping with Wellington during the Waterloo campaign, however, Muffling puts on record the reverence with which he was inspired by Wellington's character, and especially by " his openness and rectitude." He put a higher value, he declared, on Wellington's good word than on any other honour or distinction he won.

Wellington's loyalty to duty, too, was instinctive and absolute, though his conception of "duty" would hardly have satisfied a moralist or a poet. Wellington would probably have listened with quite uncomprehending ears to Bishop Hooker's fine description of duty, "whose home is in the bosom of God, and whose voice is the harmony of the universe."

But of duty as a thing to be done, the work of each day, the only thing possible or thinkable -- of this plodding and home-spun virtue -- Wellington had the clearest possible vision; it was his law of life. Some one expressed wonder once that he had accepted some post that seemed below his claims. "Why," he said, "I have eaten the King's salt, and must serve him anywhere." And duty was for him "the King's salt."

Gleig gives a picture of Wellington amongst his soldiers during the desperate fighting in the Pyrenees. " He who rode in front was a thin, well-made man, apparently of middle stature, just past the prime of life. His dress was a plain grey frock, buttoned close to the chin; a cocked hat covered with oilskin; grey pantaloons, with boots buckled at the side, and a steel-mounted light sabre. Though I knew not who he was, there was a brightness in his eye which bespoke him something more than an aide-de-camp or a general of brigade; nor was I long left in doubt. There were in the ranks many veterans who had served in the Peninsula during some of the earlier campaigns; these instantly recognised their old leader, and the cry 'Douro! Douro!' -- the familiar title given by the soldiers to the Duke of Wellington -- was raised. There was in his general aspect nothing indicative of a life spent in hardships and fatigues; nor any expression of care or anxiety in his countenance, on the contrary, his cheek, though bronzed with frequent 'exposure to the sun, had on it the ruddy hue of health, whilst a smile of satisfaction played about his mouth, and told far more plainly than words could have spoken how perfectly he felt himself at ease."

No one can realise Wellington's work in the Peninsula, or the magnificent intellectual qualities he displayed there, who does not remember the evil conditions under which that work was done. Napoleon had to reckon with no other will or judgment save his own. He was as absolute as Coesar. He was his own Minister of State, his own Commander-in-Chief, his own Chancellor of the Exchequer, the sole fountain of promotion and honour to his army. Criticism never became audible to him. The treasures and the forces of two-thirds of Europe were at his absolute disposal. He shaped his strategy in his own brain, made and unmade treaties at his mere pleasure, and moved with the uncriticised freedom and authority of a despot.

Wellington, of course, enjoyed no such autocracy. He was the servant of a Cabinet that gave him much idle advice, but neither money, supplies, nor reinforcements in the measure in which he needed them.

"I know," said Wellington afterwards, "that if I lost 500 men without the clearest necessity, I should be brought upon my knees to the House of Commons." His allies were generals who would not obey, soldiers who would not fight, and Governments without honour or loyalty.

When the English Ministers of that day -- the Portlands, the Percevals, the Liverpools -- were weak, as after Talavera. and the Walcheren expedition, they were ready to abandon Wellington; when they were strong they neglected him.

"There was nothing regular in their policy," as a keen critic said, "but confusion." Repeatedly the war in the Peninsula was brought to the point of actual collapse by mere want of specie; and it illustrates the administrative capacity of the British Government that, as Wellington's brother (the Marquis of Wellesley) complained, they despatched five different agents to purchase dollars for five different services, without any controlling head. Their agents were thus bidding against each other in every European market, and the restrictions as to the price were exactly in inverse proportion to the importance of the service. The agent for the troops in Malta was permitted to offer the highest price. Wellington was restricted to the lowest.

In a sense, Wellington's military operations were the least part of the burden that pressed on his brain. He had to teach English statesmen finance, Spanish juntas truth, the Portuguese regency honesty.

The civil administration of Portugal fell into his hands as a more detail of the war, and because, otherwise, the nation would have perished beneath the follies and corruption of its own Government. Wellington had to do his great work in the Peninsula in an atmosphere of intrigues, plots, betrayals, jealousies, and incredible stupidities, such as might have shattered the combinations of a Caesar, or wrecked the patience of William the Silent. His warfare with human selfishness, folly, and obstinacy, was more constant and exhausting than that against the French.

The fighting quality of his Spanish allies has already been described; of the Portuguese soldiers it is sufficient to say that in the earlier stages of the war they were known amongst the British rank and file as " the vamosses," from vamos, "let us be off," which they were accustomed to shout before they ran away.

It is curious that a bit of American slang can thus be traced down to the early Peninsular campaigns! Later the Portuguese rank and file under British teaching attained a respectable fighting quality; not quite so excellent, however, as might be imagined from Wellington's despatches. He praises them there, in terms in excess of their real performances, for the sake of encouraging them.

Wellington, in a word, had to run counter to national habits -- the growth of centuries, and rooted in national character -- of a singularly obstinate type. He had to teach Spaniards obedience, and Portuguese energy; to make intriguers honest, and idlers diligent, and the most loitering race in Europe prompt. And he had to do all this without the usual resources of a great commander, without the power, that is, to promote for good service or dismiss for bad service, as his personal act.

His allies had no sympathy with each other. Portugul was indifferent to the fate of Spain; Spain regarded Portugal with contempt. At times, indeed, Wellington complained that Spaniards and Portuguese hated each other more than they both hated the French. The early enthusiasm with which the English were welcomed in the Peninsula soon died out under the stern and hard experience of war.

By the Portuguese of the upper classes, at least, the British were regarded, says Napier, "as a captain regards galley-slaves. Their strength was required to speed the vessel, but they were feared and hated."

During the clouded days when the British fell back from Burgos, even the cool-headed Wellington more than once expressed his fear that a civil war would break out between the Portuguese peasantry on the one side and the British and Spaniards on the other. Both Spanish and Portuguese generals, during the same stage of the war, it may be added, were in secret communication with Joseph, arranging terms of betrayal.

Seldom, in brief, has any great general waged war under more adverse conditions than Wellington did in the Peninsula, He had to frame laws, organise finance, administer provinces, instruct politicians in their own art, and keep Parliaments from meddling, as well as watch the strategy of French marshals and the movements of French columns.

Wellington came to the Peninsula with exactly the training that fitted him for the campaigns before him. In Flanders he had learned endurance and patience. India had taught him confidence in himself and given initiative to his tactics. It had made him a diplomatist, and an unsurpassed manager of men. Had he come to Spain with nothing but a soldier's training and a soldier's gifts, he might have failed; but India had taught him to be a statesman as well.

Wellington at first, it is true, lacked one qualification for his task. He was ignorant of Spanish character. He did not know with what diligence Spanish juntas could lie, on what a scale Spanish generals could blunder , and with what promptitude and energy Spanish soldiers, leaderless and undrilled, could run away.

But he quickly learned all this. The bloody campaign of Talavera taught him the lesson. The hunger that wasted his army, the delays that taxed his patience, the broken pledges that wrecked his strategy, burned the knowledge in. He came back from his first campaign with the bitter words, "I have fished in many troubled waters; but Spanish troubled waters I will never try again!"

Chapter XII: Campaign at Talavera

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com