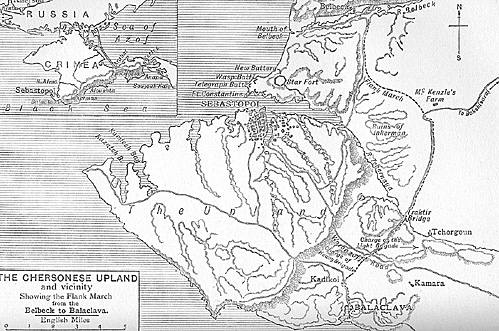

Jumbo Map: Upland Plans (extremely slow: 510K)

Immediately after he quitted Sebastopol,

Menschikoff had been joined by the remainder of his forces

in the peninsula, hitherto beyond the sphere of action, being

stationed in its south-western corner. These amounted to

12,000 men, and he also received the further reinforcements

which, as already said, were on their way from Russia. In fact,

the troops which might come to him from thence had,

practically, no other limit than the means of transporting

them. He therefore drew closer to the place, and while

keeping his main force beyond our ken, had begun on the 7th

October to send parties down to the Tchernaya. Soon

afterwards his lieutenant, General Liprandi, established his headquarters

at Tchorgoun, on the further bank, and the force of all arms

placed under him began to assemble about that place. It

gradually grew till it reached, according to Russian official

accounts, the number of 22,000 infantry, 3400 cavalry, and

seventy-eight guns, when it was considered strong enough for

immediate action.

It has been said that the valley between Balaklava and

the Tchernaya is crossed by a line of low heights, stretching

from the foot of the plateau to the village of Kamara, and that

along their course lies the Woronzoff road. Four of these

hills had earthworks on their summits--mere sketches with the

spade; a donkey might have been ridden into some of

them--and they had been armed with, in all, nine

twelve-pounder iron guns. The extent of this line of works

was more than two miles. Their garrisons had no support

nearer than the 93d regiment, and the Turks and marines

immediately around the harbour, who were 3000 yards off.

The Russians had, of course, observed this, and also the

weakness of the works, from the high hills above Kamara, and

at daybreak on the 25th October their attack began. Crossing

the Tchernaya from the Traktir Bridge upwards, and keeping at

first altogether on the side of the valley nearest Kamara, their

advanced guard came rapidly on, brought ten guns into

positions commanding the hill (known as Canrobert's Hill)

most distant from us and nearest Kamara, and began to

cannonade it. Liprandi's main body was coming up, and he at

length brought thirty guns, some of them of heavy calibres, to

bear upon Canrobert's Hill and the next to it. These

replied from their five twelve-pounders; and about this time a

troop of our horse-artillery and a field battery, supported by

the Scots Greys, were brought up to the ridge, and joined in

the artillery combat, till the troop, having exhausted its

ammunition, was withdrawn with some loss in men and

horses.

When the formidable character of the attack was seen,

our First and Fourth Divisions, and two French brigades, were

ordered down to the scene of action. Reaching the point

where the Woronzoff road descends from the plateau, the

First Division made a short halt. If its orders had enabled it to

march down to the plain there, followed by the other troops

mentioned, the enemy must have hastily withdrawn over the

Tchernaya, or have accepted battle with his back to the Kamara

Hills. Instead of this, it was marched along the edge of the

heights towards the other road down from the plateau at

Kadikoi. Moving at a height of several hundred feet above

the valley, it saw the plain spread out like a map, and what next

occurred there took place immediately below it, and in full

view. The Russians had just captured the two assailed

outworks. That on Canrobert's Hill was occupied with a

battalion of Turks and three of the guns already mentioned, the

other with half a battalion and two. After silencing the guns,

the Russians had stormed Canrobert's Hill with five battalions,

the Turks, thus outnumbered, maintaining the combat so

stubbornly that 170 of them were killed before they were

driven out Pushing on, the enemy captured more easily the

next and smaller work: and

the garrisons of the others, thus menaced by an army, and

seeing no support anywhere, hastily left them and made for

Balaklava, pursued by the cavalry, who rode through the

feeble earthworks with perfect case, seven of the nine guns

remaining in the hands of the Russians.

Near these hills the ground on either side rises to a

ridge which forms their base, thus dividing the valley into two

plains, the one on the side of Balaklava, the other stretching

to the Tchernaya, and it was these that presently became the

scene of two famous encounters.

Charge of the Heavy and Light Brigades

The Heavy Brigade of Cavalry, under General

Scarlett, had joined the army. It included the 4th and 5th

Dragoon Guards, and the 1st, 2d, and 6th Dragoons (Royals,

Scots Greys, and Inniskillings), and formed with the Light

Brigade the cavalry division commanded by Lord Lucan.

Our two cavalry brigades had been maneuvering so as

to threaten the flank of any force which might approach

Balaklava, without committing themselves to an action in

which they would have been without the support of infantry.

The Light Brigade, numbering 670 sabres, was at this moment

on the side of the ridge looking to the Tchernaya; the Heavy

Brigade, say 900 sabres, on the side towards Balaklava.

Its commander, General Scarlett, was at that moment

leading three of his regiments (Greys, Inniskillings, 5th

Dragoon Guards) through their camping ground into the plain;

a fourth, the Royals, was for the moment behind, at no great

distance, while the 4th Dragoon Guards was

moving at the moment in the direction of the Light Brigade.

Having witnessed the hasty retreat of the Turks, the many

spectators on the Upland, consisting of the French stationed

on it, and the English marching along it, next saw a great body

of Russian cavalry ascend the ridge. Scarlett, unwarned

till then, wheeled the Greys and half the Inniskillings into

line; the 5th Dragoon Guards and the other squadron of the

Inniskillings were in echelon behind the flanks; the Royals,

galloping up, formed in extension of the 5th.

The Russians, after a momentary halt, leaving the Li'ght

Brigade unnoticed, perhaps unseen, on their right, swept down

in a huge column on the Heavy Brigade, and at the moment of

collision threw out bodies in line on each flank; the batteries

which accompanied them darting out and throwing shells, all

of which burst short, against the troops on the Upland. just

then three heavy guns, manned by Turkish men and officers, in

an earthwork on the edge of the Upland, were fired in

succession on the Russian cavalry, and those troops nearest

on the flank of the column losing some men and horses by the

first shot, wavered, halted, and galloped back.

At the same moment the mass slackened its pace as it

drew near, while our men, embarrassed at first by the picket

lines of their camp, as soon as they cleared them, charged in

succession. All who had the good fortune to look down from

the heights on that brilliant spectacle must carry with them

through life a vivid remembrance of it. The plain and

surrounding hills, all clad in sober green, formed an excellent

background for the colours

of the opposing masses; the dark grey Russian column

sweeping down in multitudinous superiority of number on the

red-clad squadrons that, hindered by the obstacles of the

ground in which they were moving, advanced slowly to meet

them.

There was a clash and fusion, as of wave meeting wave,

when the head of the column encountered the leading

squadrons of our brigade, all those engaged being resolved

into a crowd of individual horsemen, whose swords rose, and

fell, and glanced; so for a minute or two they fought, the

impetus of the enemy's column carrying it on, and pressing

our combatants back for a short space, till the 4th Dragoon

Guards, coming clear of the wall of a vineyard which was

between them and the enemy, and wheeling to the right by

squadrons, charged the Russian flank, while the remaining

regiments of our brigade went in in support of those which

had first attacked.

Then--almost as it seemed in a moment, and

simultaneously--the whole Russian mass gave way, and fled,

at speed and in disorder, beyond the hill, vanishing behind the

slope some four or five minutes after they had first swept

over it.

While this was going on, four of the enemy's

squadrons, wheeling somewhat to their left, made a rush for

the entrance of the harbour. The 93d were lying down behind

a slope there; as the cavalry approached, they rose, fired a

volley, and stood to receive the charge so firmly that the

horsemen fled back with the rest of the column.

All this had passed under the observation of Lord

Raglan. He does not seem to have made any comment on

the strange inaction of the Light Brigade, which was

afterwards explained to be due to Lord Cardigan's impression

that he was expected to confine himself strictly to the

defensive.

But Lord Raglan sent the following written order to Lord

Lucan: "Cavalry to advance and take advantage of any

opportunity to recover the heights. They will be supported by

the infantry, which have been ordered to advance on two

fronts." The last sentence referred to the two English

Divisions on the march, and still at some distance.

This order did not commend itself to Lord Lucan's mind

so clearly as to cause him to act on it. He moved the Heavy

Brigade to the other side of the ridge, where he proposed to

await the promised support of infantry, and this, under the

circumstances, was not an irrational decision. After a while a

disposition seemed manifest on the Russian side to carry off

the captured guns, which might very well seem to signify a

general retreat of the forces.

Therefore a second written order was sent to Lord Lucan,

thus worded: "Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance

rapidly to the front, and try to prevent the enemy carrying

away the guns. Troop of horse-artillery may accompany.

French cavalry is on your left. Immediate."

This order was carried by the Quartermaster-General's

aide-de-camp, Captain Nolan, author of a book on cavalry

tactics, in which faith in the power of that arm was carried to

an extreme.

He found Lord Lucan between his two brigades,

Scarlett's on the further slope of the ridge, Cardigan's beyond

the Woronzoff road, where

it ascends to the Upland, drawn up across the valley and

looking down it towards the Tchernaya. D'Allon-Ville's

French brigade of cavalry had descended into the plain, and

was now on the left rear of the Light Brigade.

In order to appreciate the position of the Russian

army at this time, it is necessary to note an additional feature

of this part of the field. Rising from the bank of the

Tchernaya, close to the Traktir Bridge, and stretching thence

towards the Chersonese upland, but not reaching it, is a low

lump of hills called the Fedioukine heights. Their front

parallel to the ridge, at about 1200 yards, forms with it the

longer sides of the oblong valley leading to the Tchernaya.

Menschikoff had sent a force of the three arms to co-operatc

with Liprandi, but not part of his command; and these troops

and guns were posted on the Fedioukine heights.

The situation, then, was this: the defeated Russian

cavalry had retreated down the valley towards the Tchernaya,

and was there drawn up behind its guns, a mile and a quarter

from our Light Brigade; Liprandi's troops were posted along

the further half of the Woronzoff ridge, enclosing, with those

just said to be on the Fedioukine heights, the valley in which

the hostile bodies of cavalry faced each other ; eight Russian

guns bore on the valley from the ridge ; fourteen Russian guns

from the Fedioukine heights; Russian rifleman had been

pushed from those slopes into the valley on each side ; also on

each side were three squadrons of Russian lancers, posted in

the folds of the hills, ready

to emerge into the valley; and in front of the main body of

the Russian cavalry were twelve guns in line.

Probably anyone viewing the matter without

prepossession will think that Lord Raglan's orders to Lord

Lucan were not sufficiently precise. For instance, in the last

order, "to the front " is manifestly vague, the enemy being on

several fronts.

Lord Raglan, in a subsequent letter, explains his

meaning thus: "It appearing that an attempt was making to

remove the captured guns, the Earl of Lucan was desired to

advance rapidly, follow the enemy in their retreat,

and try to prevent them from effecting their objects." But the

enemy were not removing the guns at that time, and not

retreating, and the order, thus given by Lord Raglan under a

mistake, did not apply.

Here was plenty of room for misinterpretation; and

on receiving this order, Lord Lucan, by his own account, read

it "with much consideration--perhaps consternation would be

the better word--at once seeing its impracticability for any

useful purpose whatever, and the consequent great

unnecessary risk and loss to be incurred."

He evidently interpreted "the front" to mean his own

immediate front, and was presently given to understand that

"the guns" were those which had retired along with the Russian

cavalry. For when he uttered his objections, Nolan undertook

to reply, though there is no evidence that he had any verbal

instructions with which to explain the written order. "Lord

Raglan's orders," he said, "are that the cavalry should attack

immediately."

"Attack,sir! attack what? What

guns, sir?" asked Lord Lucan sharply.

"There, my lord, is your enemy, there are your guns,"

replied the believer in the supreme potency of cavalry,

pointing towards the valley, and uttering these words, Lord

Lucan says, "in a most disrespectful but significant manner."

Very indignant under what he held to be a taunt, Lord

Lucan thereupon rode to Lord Cardigan, and imparting to him

the order as he understood it, conveyed to him the impression

that he must charge right down the valley with his brigade as it

stood in two lines (presently made three by moving a

regiment from the first line), while the Heavy Brigade would

follow in support.

And it certainly was impossible for Lord Cardigan to

know what he could advance against except the cavalry that

stood facing him; and though he shared and echoed Lord

Lucan's misgivings, he at once gave the order, "The brigade will advance!"

With these words the famous ride began. But the

brigade was scarcely in motion when Captain Nolan rode

obliquely across the front of it, waving his sword. Lord

Cardigan thought he was presuming to lead the brigade; his

purpose could never be more than surmised, for a fragment of

the first shell fired by the enemy struck him full in the breast.

His horse turned round and carried him back, still in the

saddle, through the ranks of the 13th, when the rider, already

lifeless, fell to the ground. Led by Lord Cardigan, the lines

continued to advance at a steady trot, and in a minute or two

entered the zone of fire, where the air was filled with the

rush of shot, the bursting of shells, and the moan of bullets,

while amidst the infernal din the work of destruction went on,

and men and horses were incessantly dashed to the ground.

Still, at this time, many shot, aimed as they were at a rapidly

moving mark, must have passed over, or beside the brigade, or

between the lines. A deadlier fire awaited them from the

twelve guns in front, which could scarcely fail to strike

somewhere on a line a hundred yards wide. It was when the

brigade had been advancing for about five minutes that it came

within range of this battery, and the effect was manifest at

once in the increased number of men and horses that strewed

the plain. With the natural wish to shorten this ordeal, the

pace was increased ; when the brigade neared the battery,

more than half its numbers were on the grass of the valley,

dead or struggling to their feet; but, still unwavering, not a

man failing who was not yet disabled, the remnant rode

straight into the smoke of the guns, and was lost to view.

Lord Lucan moved the Heavy Brigade some distance

forward in support of the Light; but finding his first line

suffering from a heavy fire, he halted and retired it, not

without considerable loss.

Further Movement

At the same time another and more effectual

movement took place. General Morris, commander of the

French cavalry, directed a regiment of his chasseurs

d'Afrique (the 4th) to attack the troops on the Fedioukine

heights, and silence the guns there. The regiment ascended

the slopes, drove off the guns, and having accomplished their

object, retired, with a loss of ten killed and twenty

eight wounded. Thenceforth the retreat of our cavalry. was

not harassed by the fire of guns from this side of the field, and

the good comradeship implied in this prompt, resolute, and

effectual charge of the French was highly appreciated by their

allies, and has received just and warm praise from the

historian Kinglake.

What the Light Brigade was doing behind the smoke

of the battery was of too fragmentary a kind to be here more

than touched on. The Russian gunners were driven off, and

parties of our men even charged bodies of Russian cavalry ;

and that these retreated before them is not only recorded by

the survivors of the Light Brigade, but by Todleben. But the

combat could end but in one way, the retreat of what was left

of our light cavalry. They rode back singly, or in twos and

threes, some wounded, some supporting a wounded comrade.

But there were two bodies that kept coherence and formation

to the end. On our right, the 8th Hussars were joined by

some of the 17th Lancers, when they numbered together

about seventy men. The three squadrons of the enemy's

lancers, already said to be on the side of the Woronzoff

heights, descended from thence, and drew up across the valley

to cut off the retreat of our men. Colonel Shewell of the 8th

led this combined party against them, broke through them

with ease, scattering them right and left, and regained our end

of the valley. A little later, Lord George Paget led also

about seventy men of the 4th Light Dragoons and 11th

Hussars against the other three squadrons of lancers on the

side of the Fedioukine heights, and passed by them with a

partial collision which caused us but small loss. The

remaining regiment, the 13th Light Dragoons, mustered only

ten mounted men at the close of the action. The mounted

strength of the brigade was then 195 ; it had lost 247 men in

killed and wounded, and had 475 horses killed, and forty-two

wounded.

The First Division, after its circuitous march by the

Col, was now approaching the Woronzoff ridge, followed by

the Fourth. It could see nothing of what was occurring in the

adjoining valley; but it presently began to have tokens of the

charge, in the form of wounded men and officers who rode by

on their way to Balaklava.*

Close to the ditch of the fieldwork on the last hill of

the ridge on our side lay the body of Nolan on its back, the

jacket open, the breast pierced by the fatal splinter. It was but

an hour since the Division had passed him on the heights,

where he was riding gaily near the staff, conspicuous in the

red forage cap and tiger-skin saddle cover of his regiment.

It was now believed that a general action would begin

by an advance to retake the hills captured by Liprandi, and no

doubt such an intention did exist, but was not put in practice.

The Russians were left undisturbed in possession of the three

hills they had captured, with their seven guns. At nightfall the

First Division marched by the Woronzoff road up to the

plateau, and thence to its camp.

It was long before that road

was used again, for the presence of Liprandi's troops and

batteries rendered it unavailable during great part of the winter.

It is easier to point to the faults of the Allies than to

say how they should have been remedied. To post men and

guns in weak works commanded by neighbouring heights, and

having no ready supports in presence of an enemy's army, was

to offer them up as a sacrifice. But where were the supports to

come from?

Then it has been said that the most effective way of

bringing the Allied Divisions down from the upland would

have been by the Woronzoff road. But that is on the

supposition that it was intended to bring the Russians to a

pitched battle. That, however, if the English general thought of

it, formed no part of Canrobert's design. He believed that his

part was at present limited to pushing the siege towards the

grand object of the expedition, and covering the besieging

army from attack; and he was not to be drawn into doubtful

enterprises outside of these.

This accounted, too, for the failure to attempt the

recapture of our outworks--to what purpose retake them when

it was proved that we had not troops enough to hold so

extended aline? The ruin of the Light Brigade was primarily

due to Lord Raglan's strange purpose of using our cavalry

alone, and beyond support, for offence against Liprandi's

strong force, strongly posted; and it was the misinterpretation

of the too indistinct orders, sent with that very questionable

intention, which produced the disaster.

And yet we may well hesitate to wish that the step so

obviously false had never been taken, for the

desperate and unfaltering charge made that deep impression

on the imagination of our people which found expression in

Tennyson's verse, and has caused it to be long ago

transfigured in a light where all of error or misfortune is lost,

and nothing is left but what we are enduringly proud of.

It has been said that another blot besides Balaklava

existed in the Allied line of defence. In front of the Third,

Fourth, and Light Divisions, encamped on the strips of plain

lying between the several ravines, were the siege works, and a

direct attack made on them would be so retarded that the

Divisions could have combined to meet it. But, in the space

between the last ravine (the Careenage) and the edge of the

Upland, the circumstances were different.

A force might sally from the town, and ascending the

ravine, or the adjacent slopes, without obstacle, would then be

on fair fighting terms with whatever troops it might find

there. Or the army outside, descending from the Inkerman

heights, and crossing the valley by the bridge and causeway,

would find itself on ground well adapted for traversing the

space between the ravine and the cliff and entering the Upland

at that corner. And the result of the establishment of the

enemy's army there would be to open to it an advance which

would cause all our Divisions engaged in the siege to form to

meet it with their backs to the sea, and, in case of being

overpowered, to fall back towards the French harbour (if they

could), abandoning the siege works, with all their

material; in fact, sustaining absolute defeat, possibly destruction.

The post-road going along the causeway, and

ascending these slopes, reaches the Upland at a final crest,

from whence it passes down and across the plain to join the

Woronzoff road. It was on our side of the final ridge that the

Second Division was encamped across the post-road.

A mile behind it was the camp of the First Division.

Then came a long interval of unoccupied ground, to the French

camp on the south-eastern corner of the Upland, where

Bosquet's covering corps may be said to have been employed

in "gilding refined gold and painting the lily," by constructing

lines of defence along the edge of cliffs, several hundred feet

high, above an almost impassable part of the valley. Accepting

the broad principle that a commander can only be expected to

make good the deficiencies of an ally so far as may be without

throwing a heavy strain upon his own troops, still, in this case,

it was the common safety that was threatened, and it was a

common duty to provide against the danger.

By leaving a small force only in observation on the

impregnable heights, and placing the main body near tile really

weak point, the labour and the forces of the French,

superfluous where bestowed, might have rendered the position

practically secure. Kinglake rightly characterises the

disposition of Bosquet's corps as an example of the evils of a

divided command.

Return of the First Division

The return of the First Division to its camp may have

been unnoticed by the Russians, taking place as it

did at nightfall. They may have calculated that the advance of

Liprandi would cause the weak point on the plateau, for the

moment, to be unoccupied; otherwise it is not easy to account

for the enterprise of the day following the action of Balaklava.

At noon a force of six battalions and four light field-guns,

issuing from the town, ascended the ravine and slope which

led to the Second Division. Our pickets fell back fighting,

when the Russian field-pieces coming within range, pitched

shot over the crest, behind which the regiments of the Second

Division were lying down, while their skirmishers maintained,

with those of the Russians, a desultory combat in the hollow.

The two batteries of the Second Division now formed on the

crest, and were presently reinforced by one from the First

Division, and before their fire the Russian guns were at once

swept off the field.

The enemy's battalions then came on successively in two

columns, and these, too, were at once dispersed and driven

back by the overpowering artillery fire. The men of the

Second Division, launched in pursuit, pressed them hard, and

they never halted till they were once more within the shelter

of Sebastopol. Evans, not knowing of what force these might

be the precursors, had determined to meet them on his own

crest, and he was not to be drawn from thence till the action

was already decided.

General Bosquet sent to offer him assistance, but he

declined it with thanks, as the enemy were, he said, already

defeated. The Russians lost in this action, by their own

estimate, 250 killed and wounded, and left in our hands eighty

prisoners. We had ten killed and seventy-seven wounded. The attack,

therefore, could not be characterised otherwise than as weak

and futile.

Nevertheless, it had an object. Todleben says it was

intended to draw our attention from another attack on

Balaklava. But he is, unfortunately, so unreliable in his

statements and views that, with another plain interpretation

before us, supported by facts, we need not be drawn aside by

him. No further serious attack on Balaklava was intended, but

preparations for the battle of Inkerman were then well

advanced, and it was with these that the attack was connected.

The Russians had brought out entrenching tools with

them to Shell Hill, and, could they have established and armed

a work there, they would not only have immensely

strengthened their position in the future battle, but would also

have provided for another highly important object, namely,

the safe and unmolested passage of the troops outside

Sebastopol, across the long causeway in the valley and the

bridge of the Tchernaya. That the present attempt was not

made with a larger force was probably owing to the desire to

avoid bringing on a general action, and so anticipating

prematurely the great enterprise which took place ten days

later. But the operations of the Russians for opening that

memorable battle will be seen to prove how great would have

been their advantage had they possessed a strong lodgment on

Shell Hill.

The attack on Balaklava, and its partial success, in

depriving us of the hills held by our outposts, had effected its

purpose of weakening the forces on the Upland. The two other regiments of the Highland Brigade joined the 93d before Balaklava; some companies of the rifle battalion of the Second Division were also posted there; and

Vinoy's brigade of Bosquet's corps was so placed as to

prevent the enemy from forcing a passage to the Upland by

way of the Col. The whole of the forces under Sir Colin

Campbell now executed a complete line of defence,

strengthened with powerful batteries, around Balaklava, which

might at last be regarded as secure. Seeing what a source of

weakness the place was to us, by causing the great extension

of our line, and the absorption of so much of our

outnumbered forces, the question had been seriously

considered of abandoning it, and supplying our army from the

French harbour of Kamiesch, which would have infinitely

lightened our toils and diminished our risks. But the Commissary-General declared that without Balaklava he could not

undertake to supply the army, and the necessary evil was retained.

It was in this interval, between the sortie of the 26th

October and the battle of the 5th November, that a work was

thrown up by us on the field which, useless as a defence,

became the object of bloody conflict. It was observed that the

Russians were constructing a work on the other side of the

valley to hold two guns (probably to support the coming

attack), the embrasures being already formed, and the gabions

placed in them. On this being shown to General Evans, he had

two eighteen-pounders brought from the deppth of the siege

train, not far off, and a high parapet with two embrasures, made solid with sandbags, was thrown up on the edge of the cliff to hold them. It was placed about 1400 yards from the enemy's intended battery.

In a few rounds the Russian work was knocked to pieces,

and our guns, as being too far from our lines to be guarded,

were then removed from what became afterwards a point, in

the history of the battle, known as "the Sandbag Battery."

On the 4th of November the French infantry in the

Crimea numbered 31,000; the British, 16,ooo; the Turks, who

were not permitted to develop their value, 11,000. They must

have been very different from the Turkish soldiery of the

present day if they were not equal ill fighting quality to any

troops in the Crimea, and superior to all in patience,

temperance, and endurance. But it was a tendency of the time

to disparage them, partly from their abandonment of the

outposts at Balaklava, the valorous defence made by a great

part of them being, from some accident, unknown at the time;

and they were employed in ways which gave them no

opportunity of helping us in battle.

On both the Allied and the Russian side it was known

that a crisis was now rapidly approaching; but only the

Russians knew that it was a race between them for delivering

the attack. The French siege corps, comparatively strong,

close to its base, and protected on both flanks, on one by the

sea, on the other by the English, was now retrieving its

disaster of the 17th October, by diligently pushing its

approaches in regular form upon the Flagstaff Bastion. We

were strengthening our batteries and replenishing our

magazines; as has been said

the Russian daily loss in the fortress far exceeded ours in the

trenches. We were ready to support a French attack which

would now be made over a very short space of open ground.

On the 4th November the Allied commanders had

appointed a meeting on the 5th for definitely arranging the

cannonade and assault which, they hoped, would at length lay

the fortress open to us. The Russians were, of course, alive to

the peril. But, on the 4th they had completed the assembly of

their forces for attack.

For long the corps d'armee stationed about Odessa had

been in motion for the Crimea. It had repeatedly sent

important reinforcements to the fortress, and the whole of

those, which had reached the heights beyond the Tchernaya by

the 4th November, raised the total of Menschikoffs forces in

and around Sebastopol, according to Todleben, to 100,000

men, without counting the seamen, so that not less than

110,000 to 115,ooo men were confronting the 65,000 which,

counting seamen and marines, the aggregate of the Allied

forces amounted to.

Of the Russian troops which took actual part in the

battle of Inkerman, 19,000 infantry, under General

Soimonoff, were within the fortifications of Sebastopol;

16,000, under General Pauloff, were on the heights beyond

the Tchernaya. These were to combine for the attack,

accompanied by fifty-four guns of position and eighty-one

field-guns.

On their left was the force which had been Liprandi's,

now commanded by Prince Gortschakoff, stretching from the

captured hills outside Balaklava, across the Fedioukine

heights, into the lower valley

of the Tchernaya. The remainder of the troops formed the

ample garrison of the works of Sebastopol. Long before the

November dawn of Sunday, the besiegers heard drowsily in

their tents the bells of Sebastopol celebrating the arrival in

the camp of the young Grand Dukes Michael and Nicholas,

and invoking the blessings of the Church on the impending

attack, towards which the Russian troops were even then on

the march.

Chapter VII: Battle of Inkerman

The drama now shifted into a new act, in which the Allies

were to be themselves attacked, and forced to fight for their

foothold in the Crimea.

The drama now shifted into a new act, in which the Allies

were to be themselves attacked, and forced to fight for their

foothold in the Crimea.

(*The commander of the Royals, Colonel Yorke, rode by the

writer with a shattered leg. He died in 1890, while this chapter was being

written, at the age of seventy-seven.)

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com