Battle of Inkerman (extremely slow: 690K)

But speedy reaction must have followed

when his military counsellors showed how hopeful was the

situation. His enemies were now definitely lodged in a small

corner of the Crimea, and bound to it by their dependence

on the fleet; Sebastopol was amply garrisoned and the

fortifications daily grew stronger; the field army assured the

concentration of the troops which we

crowding the roads of Southern Russia; behind them the

resources in men and material were almost boundless. Only

there was this limitation, that a season was near when the

march of troops towards and along the Crimea would be

almost impossible. But there was ample time to do all that was

needful to raise the Russian Forces to an overwhelming

preponderance; and their point of attack, offering at once the

greatest advantages for entering on the battle, and the most

complete results as the fruits of victory, was so obvious that it

might almost be fixed, and the details arranged, at St

Petersburgh.

Probably it was so arranged; rumours began to pass

through Europe of a great disaster impending over the

invaders, and a paper was communicated to our Foreign

Office, purporting to be a copy of a despatch from

Menschikoff for transmission to the Czar, and believed to be

authentic, which said, "Future times, I am confident, will

preserve the remembrance of the exemplary chastisement

inflicted upon the presumption of the Allies. When our

beloved Grand Dukes shall be here, I shall be able to give up to

them intact the precious deposit which the confidence of the

Emperor has placed in my hands. Sebastopol remains ours."

This confidence was amply justified by the situation. But

while such were the views of the enemy, only a few in the

Allied Armies foresaw this particular danger. Evans, whose

apprehensions were intensified by his responsibility as

commander of the troops on that part of the ground, had

indeed for long felt uneasy at our want of protection there, and

had even begun a line of entrenchment to cover his guns; but it was not more than

begun, and on the day of battle the ground was marked only by

two small fragments of insignificant entrenchment, not a

hundred yards long in all, and more like ordinary drains than

fieldworks, one on each side of the road as it crossed the

crest behind which the Second Division was encamped.

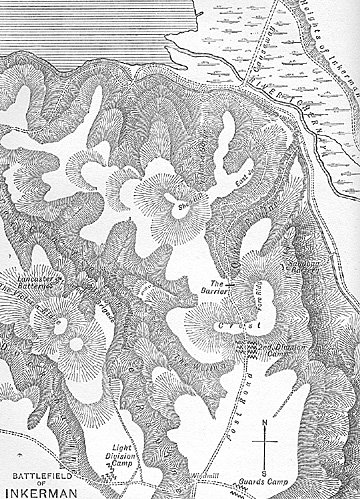

Ground

Inkerman was not the name of the ground on which

the battle was fought, and which probably had no name, but

was taken from the heights beyond the Tchernaya. Opposite

the cliff which supports the north-eastern corner of the

Upland rises another, of yellow stone, honey-combed with

caverns, and crowned with a broken line of grey walls,

battlemented in part, and studded with round towers. These are

the "Ruins of Inkerman," and around them masses of grey

stone protrude abruptly through the soil, of such quaint,

sharp-cut forms that in the distance they might be taken

for the remains of some very ancient city. From these the hill

slopes upward to a plateau, mostly invisible from our

position, where Menschikoff's field army was assembled.

It is from this locality, the features of which are so

striking to the eye when viewed from the British position, that

the corner of the Upland, bounded on the west by the

Careenage ravine, and on the north by the harbour, has

received the name of Mount Inkerman.

The Second Division camp stood on a slope, rising

beyond it to a crest, which, nearly level for most of its width,

bent down on the right to the top of the cliffs above the

Tchernaya, on the left to the Careenage

ravine, the extent from the one boundary to the other being

about 1400 yards. On ascending to this crest, and looking

towards the head of the harbour, the ground beyond was seen

bending downward into a hollow, and again rising to a hill

opposite, which, with its sloping shoulders, limited the view

in that direction to about 1200 yards.

This opposite summit was Shell Hill, the post of the

Russian artillery in the engagement, and the space between

that and our crest comprised most of the field of battle, the

whole of which was thickly clad with low coppice, strewn

throughout with fragments of crag and boulders. A very few

natural features marked the field.

About 500 yards from its right boundary, our crest,

instead of sloping down to the front as elsewhere, shot

forward for about 500 yards, in what Mr Kinglake calls the

Fore Ridge, and from the spine of this eminence the ground

fell rapidly, still covered thickly with stones and coppice, to

the edge of the cliffs, where, at a point abreast of the northern

end of this Fore Ridge stood the famous Sandbag Battery on a

point (called by Kinglake the Kitspur), isolated to some

extent by a small ravine plunging north-east to the valley.

Two other natural features complete the general

character of the field, namely, two glens, which half way

between our crest and Shell Hill, at the bottom of the dip,

shot out right and left, narrowing the plateau between them to

half its width, till it expanded again as they receded from it at

the bases of Shell Hill.

Menschikoff, whose plans of battle always showed

how vague were his ideas about tactics, gave general orders

to this effect: General Soimonoff was to assemble within the

works his force of 19,000 infantry and thirty-eight guns, and

issue from them, near the mouth of the Careenage ravine; at

the same time, General Pauloff, with his 16,000 infantry and

ninety-six guns, was to descend from the heights, cross the

causeway and bridge of the Tchernaya, and "push on

vigorously to meet and join the corps of Lieutenant-General

Soimonoff."

In another paragraph of the orders the object of the

operation is stated to be to attack the English "in their

position, in order that we may seize and occupy the heights on

which they are established."

The forces in the valley, lately commanded by Liprandi,

now by Gortschakoff, were "to support the general attack by

drawing the enemy's forces towards them, and to endeavour to

seize one of the heights of the plateau."

The garrison of Sebastopol was to cover with its artillery

fire the right flank of the attacking force, and in case of

confusion showing itself in the enemy's batteries, was to

storm them. These being the general directions, the execution

of them was left to the different commanders, namely, for the

main attack to Soimonoff and Pauloff, for the auxiliary

operations to Gortschakoff and the commandant of Sebastopol.

If these orders had been destined to be carried out

under Menschikoffs own superintendence, their vagueness

might be excusable. But, regarding himself apparently as the

commander of all the forces in the locality, he committed the

direction of the two bodies who were to make the main attack

to another officer, General Dannenberg, who was to take

command of them "as soon as they shall have effected their junction."

This general only received his orders at five o'clock in

the evening of the 4th, and neither he nor Menschikoff

appears to have been then aware of the obstacle which the

Careenage ravine -- the sides of which were nearly

inaccessible -- offered to the combined action of troops

astride of it, and both of them dealt with the ground on both

sides of it as one clear battlefield.

After many perplexing orders had been issued,

Darmenberg seems to have at length realised the nature of the

chasm that would intersect his front, and he therefore made

further arrangements for the advance of his two generals on

the two sides of it. But Soimonoff had interpreted the orders

of the Commanderin-Chief as directing him to advance on the

eastern side of the ravine; he had framed his plan for the

movement, and submitted it to Menschikoff, who, though he

must have seen how it conflicted with Darmenberg's scheme,

seems to have made no attempt to decide between them.

Soimonoff, therefore, followed his own idea, and thus it came

to pass that 35,000 men, with 134 guns, were crowded into a

space insufficient for half their numbers, while Dannenberg,

who possibly only learned on the field of this wide departure

from his design, was left to conduct an enterprise the plan of

which he could not approve.

No Man's Land

Here a moment's pause may be made to point out

that, when two bodies of troops, separated by a distance of

several miles, were to move by narrow issues to the ground

where they were to join forces, it would have been an

immense advantage to possess a commanding fortified point

between them and the enemy. Shell Hill

would have been such a point, and that circumstance will be

seen to be amply explanatory of the Russian design in the

action of the 26th of October.

Against the formidable attack in preparation, the

menaced ground was then occupied by very nearly 3000 men

of the Second Division, placed on the alert by the attack on

their outposts. On the adjoining slope, the Victoria, was

Codrington's Brigade, which, with some marines, and three

companies brought in the course of the action from Buller's

Brigade, numbered 1400o men, and, as these might be

regarded as partly the object of the attack, they remained

throughout the action on the same ground. Close to them was

the Naval Battery, which had been placed to fire on the

Malakoff, but four of its heavy guns had been withdrawn to

the siege works, and only one remained, which could not be

brought to bear till the close of the battle.

Three-quarters of a mile in rear of the Second

Division was the brigade of Guards, which was able to bring

into action 1331 men.

Two miles in rear of the Second Division were the

nearest troops of Bosquet's army corps, stretched round the

south-eastern corner of the Upland.

Buller's Brigade, on the slope adjoining Codrington's,

was a mile and a half from the Second Division. Cathcart's

Division (Fourth), two miles and a half from the Second

Division, and England's (Third), three miles, were on the

heights in rear of our siege batteries.

Soimonoff issued from the fortress before dawn,

crossed the Careenage ravine, and ascended the northern

heights of Mount Inkerman, where at six o'clock he began to

form order of battle. For some reason never explained, he

disregarded that part of the plan which prescribed that he

should combine with Pauloff, and act under the orders of

Dannenberg. Waiting for neither, he at once commenced the

attack. Spreading 300 riflemen as skirmishers across his

front, he formed his first line of 6000 men, and the second, in

immediate support, of 3300.

The advance of these would cover the heavy batteries,

numbering twenty-two guns, which he had brought from the

arsenal of Sebastopol. These, corresponding to our eighteen-

pounder guns and thirty-twopounder howitzers, were posted

on Shell Hill, and the high slopes which buttressed it right and

left. Behind them came his 9000 remaining infantry, as a

general reserve, and the light batteries (sixteen guns) which

formed the remainder of his artillery. These operations were

completed by about seven o'clock, when the heavy batteries

opened fire, and his lines of columns descended the hill.

The pickets of the Second Division, each of a

company, and numbering altogether 480 men, were at once

pressed back fighting. But the main body of the Division, not

ranged on the crest as in Evans's recent action, was pushed in

fractions at once down the hill to support the pickets, by

Pennefather, who commanded in the temporary absence of

Evans, then sick on board ship.

He was probably less impelled to this mode of action

by any tactical reasons, though these, too, favoured it, than by

his fighting propensity, which always led him to make for his

enemy. Consequently, the crest was

held only by the twelve nine-pounder guns of the Division,

and a small proportion of its infantry. The large Russian

projectiles not only swept the crest, but completely knocked

to pieces the camp on the slope behind it, and destroyed the

horses tethered there.

Morning Attack

The morning was foggy, the ground muddy, and the

herbage dank. The mist did not, however, envelop the field.

Shell Hill was frequently visible, as well as Codrington's

troops across the ravine, and columns could sometimes be

descried while several hundred yards off. It was chiefly in the

hollow that the mist lay, but even here it frequently rose and

left the view clear. No doubt it was favourable to the fewer

numbers, hiding from the Russians the fact that there was

nothing behind the English lines, which came on as boldly as

if strong supports were close at hand. It needs some

plausible supposition of that kind to account (however

imperfectly) for the extraordinary combats which ensued,

where the extravagant achievements of the romances of

chivalry were almost outdone by the reality.

On reaching the point of the plateau where it was

narrowed by the glens, the Russian battalions halted to give

their guns time to produce their effect. When they resumed

their march, the battalion columns on the right passed first,

and thus our left was the part of our line which received the

first attack. It is to be noted as a feature of the field that at the

point where the postroad enters the Quarry ravine, and where

we had a picket, a wall of loose stones, crossing the road and

stretching into the coppice on each side, had been thrown up

as a slight defence, and to mark the ground, and this was known

as " the Barrier."

Here it must be remarked that the indefatigable

inquiries of Kinglake, and the care with which he arranged the

information thus obtained, first disentangled the incidents of

the battle from the confusion which long hid them, and

rendered them intelligible, as they had never been before,

even to those who fought in the action.

The enemy, unable to advance through the narrowed

space on a full front, such as would have enabled him to make

a simultaneous attack all along our position, entered it with

his right in advance of the centre and left, and the first attack

therefore took place on our left. Only his foremost battalions

being visible, the nature of the attack was not at first fully

appreciated, and might have been supposed to be merely a

very formidable sortie.

His battalions advanced, some in a column composed

of an entire battalion, some split into four columns of

companies, but the broken nature of the ground dissolved all

these more or less into dense crowds which had lost their

formation. One of these, on the extreme Russian right,

preceding for some unexplained reason the others, pressed on

till it came in contact with a wing of the 49th, which,

delivering a volley, charged, drove it back, and pursued it even

on to the slope of Shell Hill.

Soimonoff then led in person twelve battalions,

numbering 9000 men, against our left and centre, while a

column * moved up by the Careenage ravine beyond our left

flank. At the same time there were arriving on our left 65o men

of the Light Division, and a battery from the Fourth Division,

raising Pennefather's force on the field to exactly 36oo men

and eighteen field-guns. About 400 of Buller's men (88th),

which had at first passed over the crest, fell back before the

Russian masses, and three guns of the battery which was

following them fell into the enemy's hands. At the same time

the Russian column in the ravine, after surprising a picket of

the Light Division, was making its way to the plateau in rear of

our line, and close to our camp, by a glen which led in that

direction. It was only just in time that Buller himself

arrived with the remainder of his 650 men (77th), who were at

once pushed into the fight. Part of them attacked the head of

the turning co umn just emerging from the glen, while a

company of the Guards, on picket on the other bank, fired on

it from thence, and the column, which had so nearly attained

to success that might have been decisive, was driven back, and

appeared no more on the field, Soimonoff's right battalion,

advancing on the plateau, was encountered by a wing of the

47th, spread out in skirmishing order on a wide front, which

harassed it by so destructive a fire that it broke up and

retreated, and two other battalions of the same regiment (the

same which had just captured our guns) came to a halt, having

before them the troops which had pursued the Russian

battalions that first met us to the slope of Shell Hill, and had

then fallen back. Passing these on the right, Buller's

companies (260 men of the 77th) entered the

fight, met two Russian battalions, fired, charged, and drove

them quite off the field. Seeing this discomfiture of their

comrades going on so near, the other battalions just spoken

of as halted on our left of these, followed them in their

retreat, leaving the captured guns to be recovered by our men.

It was about this time that Soimonoff was killed. On our side

General Buller was disabled by a cannon shot which killed his horse.

Five of the twelve battalions, besides that other which

attacked first, and the turning column in the ravine, were thus

accounted for. Seven of Soimonoff's still remained. One of

these diverged to the Russian left, where it joined part of

Pauloff's forces, then arriving on the field. The remaining

six advanced by both sides of the post-road upon our centre,

and were defeated like the rest, partly by the close fire of the

battery on our left of the post-road (that on the right had been

silenced by the fire from Shell Hill), partly by the charge and

pursuit of some companies of the 49th, and the pickets which

had halted here, and which held the ground beside the guns.

The part of Pauloff's corps, eight battalions, which

preceded the rest had meanwhile crossed the head of the

Quarry ravine, and, picking up the stray battalion of

Soirnonoff, and raising the whole force employed by the two

generals in the first attack to twenty battalions, numbering

15,000 men, made a simultaneous but distinct onset. They had

formed opposite our right, their left on the Sandbag Battery,

their right across the post, road where it enters the Quarry

ravine.

The four battalions composing the regiment on the

right had begun to approach the Barrier) when a wing of the

3oth, 200 strong, sprang over it, and charged with the bayonet

the two leading battalions. A short and very serious conflict

ensued-many of our men and officers were shot down ; but

the charge proved decisive, and the leading battalions,

hurrying back in disorder, carried the two others (of the same

regiment) with them, and the whole were swept off the field,

some towards Shell Hill, some down the Quarry ravine to the

valley.

Finally, it remained to deal with the five battalions

still left of the attacking force. Against these advanced the

41st regiment, under its brigadier, Adams, numbering 525 men.

Approaching from the higher ground of the Fore Ridge, the

regiment, in extended order, opened fire on the 4000

Russians before it, drove them over the declivities, and from

the edge pursued them with its fire till they reached and

descended the bank of the Tchernaya.

Thus, in open ground, affording to the defenders none

of the defensive advantages, walls, hedges, or enclosures of

any kind, which most battlefields have been found to offer,

these 15,000 Russians had been repulsed by less than a fourth of

their numbers. But, in truth, to say they were repulsed very

inadequately expresses what happened to them in the

encounter. All the battalions which did not retreat

without fighting left the field so shattered and disorganised,

and with the loss of so many officers, that they were not again

brought into the fight. This was in great measure owing to the

density of the formations in which the Russians

moved, and the audacity with which our slender bodies

attacked them. Seeing the British come on so confidently, on

a front of such extent as no other European troops would, at

that time, have formed without very substantial forces behind

them, the Russians inferred the existence of large numbers,

and remained convinced that they had been forced from the

field by masses to which their own were greatly inferior.

This was a moral effect; but there was also a material

cause conducing to the result. The Russian riflemen, as we

soon had good reason to know, were armed with a weapon

quite equal to our Minie; but the mass of the infantry still

wielded a musket not superior to the old Brown Bess firelock,

which the Minie had replaced, whereas our troops, except

those of the Fourth Division, had the rifle. Therefore,

long before a Russian column had got near enough to make its

fire tell, it began to suffer from a fire that was very

destructive, not only because of the longer range and more

effective aim, but because the bullets were propelled with a

force capable of sending them through more than one man's

body. But these reasons are merely palliative; nothing can veil

the fact that, supported by an overwhelming artillery, which

frequently reduced ours to silence, these great bodies, once

launched on their career, ought by their mere impetus to have

everywhere penetrated our line; and that had even a part been

well led, and animated by such a spirit as all nations desire to

attribute to their fighting men, they would never have suffered

themselves to be stopped and turned by the imaginary enemies

which the mist might hide, or which the intrepid, gallant,

audacious bearing of our single line caused them to believe

might be following in support of it.

New Stage of Action

It was half-past seven when this stage of the action

was finished, and a new one commenced with the arrival on

the scene of General Dannenberg. All Pauloffs battalions

were now ranged on Mount Inkerman, and with those of

Soimonoff which had previously been held in reserve, and

were still untouched, raised the number of fresh troops with

which he could recommence the battle to 19,000 infantry and

90 guns. Ten thousand of these were now launched against our

position, but this time they were massed for the attack chiefly

in and about the Quarry ravine, and, neglecting our left, bore

against our centre and right, upon which also was now turned

the weight of the cannonade. The reason for this, no doubt,

was that closer co-operation might be maintained with

Gortschakoff, whose troops had extended down the valley till

their right was nearly opposite the right of our position, and

who, in case of Dannenberg's success in that quarter, might at

once lend a hand to him.

At the same time Pennefather also had received

reinforcements. The Guards, turning out at the sounds of

battle, had now reached the position; so had the batteries of

the First Division ; and Cathcart was approaching with 2100

men of his Division, set free by the absence of any sign of

attack upon the siege works.

The troops which had at first so successfully de.

fended the Barrier had been compelled, by the large

bodies moving round their flanks, to fall back, and the

Russians held it for a time. But these were driven out. and the

barrier was reoccupied by detachments of the 21st, 63d, and

Rifles, when, from its position, closing the post road, it

continued to be a point of great importance. The troops there,

reinforced from time to time, held- it throughout the battle,

repelling all direct attacks upon it; and it is a singular fact that

the enemy's masses, in their subsequent onsets, passed it by,

both in advancing and retreating, without making any attempt

upon it from the rear.

The first attack was made on Adams, with five Russian

battalions, numbering about 4000 against the 700 that opposed

them, and took place on the slopes of the Fore Ridge, and

about the Sandbag Battery. The Guards, already on the crest,

were moved to the support of Adams. Whether the troops

of Pauloff were superior in quality, or better led, or whether

the lifting of the fog revealed their own superiority in

number, the spirit they displayed was incomparably fiercer

and more resolute than had yet marked the attack. The

conflicts of the first stage of the battle had been child's play

compared with the bloody struggle of which the ground

between the Fore Ridge and the edge of the cliffs east of it

were now the scene. Useless for defence on either side,

the Sandbag Battery may be regarded as a sort of symbol of

victory conventionally adopted by both, leading our troops to

do battle on the edge of the steeps, and the enemy to choose

the broken and difficult ground on which this arbitrary

standard reared itself to view for

a main field of combat. Although the disparity of numbers was

now diminished, the Russians, instead of shrinking from

difficulties which their own imaginations rendered

insurmountable, or accepting a repulse as final, swarmed again

and again to the encounter, engaging by groups and individuals

in the closest and most obstinate combats, till between the

hostile lines rose a rampart of the fallen men of both sides.

For a long time the part played by the defenders was

strictly defensive ; with each repulse the victors halted on the

edge of the steeps, preserving some continuity of front with

which to meet the next assault, while the recoiling crowds,

unmolested by pursuit, and secured from fire by the

abruptness of the edge, paused at a short distance below to

gather fresh coherence and impetus for a renewal of the

struggle. It was with the arrival of Cathcart, conducting

part of the Fourth Division, that the combat assumed a new

phase. Possessed with the idea of the decisive effect which an

attack on their flank must exercise on troops that, however

strong they might still be in numbers, had already suffered so

many rebuffs, he descended the slope beyond the right of our

line. The greater part of his troops had already been cast

piecemeal into the fight in other parts of the field where

succour was most urgently needed, but about 4oo men

remained to him with which to make the attempt. And at first

it was eminently effective, insomuch that Cathcart

congratulated his brigadier, Torrens, then lying wounded, on

the success of this endeavour to take the offensive. But that

success was now to be turned into

disaster by an event which it was altogether beyond Cathcart's

province or power to foresee. While advancing in the

belief that he was in full co-operation with our troops on the

cliff, he was suddenly assailed by a body of the enemy from

the heights he had just quitted, and which had either turned or

broken through that part of our front which he was

endeavouring to relieve from the stress of numbers. Thus

taken in reverse, his troops, scattered on the rugged hillside,

suffered heavily, only regaining the position in small, broken

bodies, and with the loss of their commander, who was shot

dead. This effort of Cathcart's changed the restrained

character of the defence, and was the first of numerous

desultory onsets, which left the troops engaged in them far in

advance, and broke the continuity of the line. For the

downward movement had spread from right to left along the

front; the heights of the Fore Ridge, left bare of the

defenders, were occupied by Russians ascending the ravine

beyond their left ; and our people, thus intercepted, had to

edge past the enemy, or to cut their way through. The

right of our position seemed absolutely without defence; a

body of Russian troops was moving unopposed along the Fore

Ridge, apparently about to push through the vacant corner of

the position, when, in order to enclose our fragments, it

formed line to its left, facing the edge of the cliffs. It was

while it stood thus that a French regiment, lately arrived, and

thus far posted at the English end of the Fore Ridge, advanced,

took the Russians in flank, and drove them back into the

gorges from whence they had issued.

Next Attack

The next attack was made by the Russians with the

same troops, diminished by their losses to 6000 men, while

the Allies numbered 5000. The disparity in infantry for the

actual encounter (for the Russian rcserve of 9000 was still

held back) was thus rapidly diminishing, but the enemy

preserved his great predominance in artillery. Again the

hundred guns, which by this time they had in action, swept our

crest throughout its extent. The right of our position, from

the head of the Quarry ravine to the Sandbag Battery, was now

held by some of our rifles, and by a French battalion. Leaving

these on their left, the enemy's columns issued from the

Quarry ravine, and this time pushed along the post-road against

our centre and left. Two of their regiments (eight

battalions) were extended in first line, in columns of

companies; behind came the main column, composed of the

four battalions of the remaining regiment. This advance was

more thoroughly pushed home, and with greater success, than

any other which they attempted throughout the day. They once

more made their right the head of the attack, and with it

penetrated our line on the side of the Careenage ravine, drove

back the troops there, and took and spiked some of our guns.

The other parts of their front line, coming up successively

to the crest, held it for a brief interval, while the main column,

passing by our troops at the Barrier, moved on in support. But

meanwhile, before it reached the crest, the regiments of the

front line had been driven off by a simultaneous advance of

French and English, and, after suffering great loss, the main

column also retired. It was pressed by the Allied troops, part

of whom reinforced those already at the head of the Quarry

ravine, while the French regiment, which had defended the

centre, moving to its right, took up, with the other already

there, the defence of the ground where the Guards had fought.

Here the French had yet another struggle to maintain, and with

varying fortunes, for once they entirely lost the advanced

ground they had held; but their last reinforcements arriving,

they finally drove the Russians immediately opposed to them

not only off that part of our front, but off the field.

It was now eleven o'clock, and the battle, though not

ended, was already decided. For not only had the Allies, after

deducting losses, 4700 English and 7000 French infantry on

the field, against the broken battalions and the 9000 unused

infantry of Dannenberg's reserve, but the balance of artillery

power, for long so largely against us (the Allies had in action

at the close only thirty-eight English and twenty-four French

fieldguns) had now been for some time in our favour.

At half-past nine the two famous eighteen-pounders

had appeared on the field. Forming part of the siege train,

they had as yet been left in the depot near the First Division

camp, and were now dragged on to the field by 150

artillerymen. Their projectile was not much larger than that of

the heavy Russian pieces; but the long, weighty iron gun, with

its heavy charge, was greatly more effective in aim and

velocity. The two, though not without heavy losses in men,

spread devastation among

the position batteries on Shell Hill and the lighter batteries on

its slopes; while two French batteries of horse-artillery,

passing over the crest on the right of our guns, had established

themselves on the bare slope fronting the enemy, and had

there gallantly maintained themselves under a shattering fire.

For long this combat of artillery was maintained on both

sides, though with manifestly declining power on the part of

the enemy, while our skirmishers, pressing forward on the

centre and left, made such way that they galled the Russian

gunners with their bullets.

The menace of an attack by Gortschakoff on the

heights held by Bosquet had not been without its effect. For an

hour, while the real fight was taking place at Inkerman, the

French troops were kept in their lines. At the end of that time

Bosquet sent two battalions from Bourbaki's Brigade, and two

troops of horseartillery, to the windmill on the road near the

Guards' camp, and accompanied them himself. He was there

met by Generals Brown and Cathcart, to whom he offered the

aid of these troops, and expressed his readiness in case of

need to bring up others.

The generals took the strange, almost unaccountable,

course of telling him that his support was not needed, and

asking him to send his battalions to watch the ground on the

right of the Guards' camp left vacant by the withdrawal of the

Guards to take part in the battle. Bosquet had thereupon

returned to his own command; but receiving fresh and

pressing communication from Lord Raglan

victory, which could scarcely have been bought too dear. A

real attack would undoubtedly have kept Bosquet from parting

with his troops; Dannenberg, in their absence, would have

penetrated our line, and opened the road to the valley, when

Gortschakoff would have joined him on the Upland.

It was in expectation of such an effort on Gortschakoff's

part that Dannenberg remained on the field long after he had

abandoned the intention of resuming his independent attacks.

He held his ground, though suffering heavy losses, trusting

that the storming of the heights lately held by the French, but

now comparatively bare of troops, would open a road for

him, and straining his ear for the sound of his colleague's guns

on the Upland.

At last the decline of the autumn day forced him to begin

that retreat which the declivities in his rear rendered so

tedious and so perilous, encumbered as he was by a numerous

and disorganised artillery. Canrobert has been blamed for not

attacking him with the Sooo troops he had assembled on the

field, the greater part still unused ; and doubtless had the

French general taken a bold offensive, the enemy's defeat

would have become a signal disaster. But if Dannenberg was

looking towards Gortschakoff, so, no doubt, was Canrobert.

He could not but remember that the 20,000 troops whom he

had watched so anxiously in the morning were still close at

hand in order of battle ; the policy he had declared at Balaklava

of restricting himself to covering the siege, no matter what

successes a bold aggression might promise, governed him

now; and this seems, in the case of a gallant, quick.

spirited man like Canrobert--one, too, whom we had often

found so loyal an ally--a more plausible explanation of his

almost passive attitude at the close of the battle, than either a

defect of resolution or a disinclination to aid his colleague.

This extraordinary battle closed with no final charge

nor victorious advance on the one side, no desperate stand nor

tumultuous flight on the other. The Russians, when hopeless

of success, seemed to melt from the lost field; the English

were too few and too exhausted, the French too little

confident in the advantage gained, to convert the repulse into

rout. Nor was there among the victors the exaltation of spirit

which usually follows the gain of a great battle, for the stress

of the conflict had been too prolonged and heavy to allow of

quick reaction.

The gloom of the November evening seemed to

overspread with its influence not only the broken battalions

which sought the shelter of the fortress, but the wearied

occupants of the hardly-contested ground, and descended on a

field so laden with carnage that no aspect of the sky could

deepen its horrors. Especially on the slopes between the Fore

Ridge and the cliffs had death been busy; men lay in swathes

there, as if mown down, insomuch that it was often impossible

to ride through the lines and mounds of the slain.

Of these, notwithstanding that the Allies, especially

the English, had lost heavily in proportion to their numbers, an

immense and almost unaccountable majority were Russians;

so that of no battle in which our nation has been engaged since

Agincourt could it be more truly said,

The Russian losses in the battle were four times as

great as the number of the troops with which the Second

Division met the first attack. They lost 12,000, of which an

immense proportion were left dead on the field, and 256

officers. The English lost 597, of whom thirty-nine officers,

killed, and 1760, of whom ninetyone officers, wounded ; the

French, thirteen officers and 130 men killed, and thirty-six

officers and 750 men wounded.

The present writer does not doubt that Darmenberg's

plan of attacking by both sides of the Careenage ravine was

the right one. It is true that to have attacking troops divided by

an obstacle is a great disadvantage. It is also true, as Kinglake

says, that "the camps of the Allies were so placed on the

Chersonese that, to meet perils threatening from the western

side of the Careenage ravine, they could effect a rapid concentration."

But they could only effect it by robbing the eastern

side of what was indispensable for its defence. If, instead of

one part of the enemy's army attacking while the other was

coming up in its rear, and therefore exercising no effect upon

the battle, both had attacked simultaneously, it is hardly

credible that one (and if one, both) would not have broken

through. And if it is a disadvantage that the front of attack

should be divided by an obstacle, it is

a still greater evil to restrict the attack, especially against very

inferior numbers, to too confined a space. By crowding on to

the eastern slope only, in numbers amply sufficient to have

attacked both, the Russians were choosing the ground which

best suited our numbers and our circumstances, and which

least suited their own.

It has been already remarked that as the mode of

fighting the action by us differed radically from that of the

26th of October, so did the circumstances on the two days.

On the 26th we had a great superiority in artillery, and plenty

of room on the crest for the eighteen guns and the small force

of infantry. On the 5th November nearly half of our

narrow position was occupied by the line of batteries. Where,

then, were the infantry to be posted? Were they to be close in

rear of the batteries ? Then the tremendous fire of the enemy

would have swept the crest with double effect, ravaging both

guns and infantry. If posted in front of the guns, the result

would be the same, with the additional disadvantage that our

guns would be firing over the heads of our infantry. By

pushing the troops down the slope, they met the enemy before

their columns could issue from the ravines and deploy; and

even on the extreme right we are by no means certain that to

encounter them on the ledge near the Sandbag Battery (a

mode of action which Mr Kinglake laments as false policy)

was not the best way of dealing with the ground, for if we had

withdrawn our line there to the main crest, and left the space

between the cliff and the Fore Ridge unoccupied, the Russians, after ascending to the ledge, would have been able to take breath beneath its shelter before gaining the plateau, and when there they would have had the

opportunity of solving what was one of their great difficulties

throughout the day, namely, finding open space to deploy on

at a certain distance from our front. As it was, they came

up rugged steeps, in disorder and under fire, to close with us

still uphill, while yet breathless with the ascent, and here

consequently occurred their severest losses. On the whole,

therefore, the manner in which our troops fought the battle

may be thought to have been very fortunately adapted to the

topography of the field, and to the proportions of the

contending forces.

It is natural that a Russian chronicler should seek to

extenuate this defeat, and we will not greatly blame Todleben

for increasing the strength of the English, in the first phase of

the combat, to 11,585 (more than trebling their actual force),

for laying great stress on the "fieldworks" which strengthened

the position, and for claiming successes which, in some

mysterious way that he does not elucidate, were turned into

disasters.

In his visit to the field, in 1869, Mr Kinglake found

the Sandbag Battery still there--very likely it is there now--

and his detailed account of it is sufficiently exact. But he and

other chroniclers advert to it, when describing the combats of

which the area around it was the scene, in terms which would

convey to those who have never seen it an altogether

exaggerated idea of its importance, and even

of its size; and Todleben not only describes a Russian

regiment 3000 strong as fighting desperately with our

Coldstrearns for the possession of it, but as capturing nine

pieces of artillery "as the prize of this brilliant feat of arms";

some of which, that imaginative chronicler tells us, were

carried off by the victors, and the rest spiked.

It is true that some hours later in the day one French gun

was carried off from this part of the field, and was afterwards

recovered in a ravine, so the Russian historian could at least

plead that his version is not in this case, as it is in some

others, absolutely without foundation. But all this gives to the

battery an importance quite fictitious.

It was simply a wall of earth, several feet thick and twelve

paces long, with two embrasures cut in it, the parapet,

elsewhere considerably taller than a man's head, sloping

rapidly for a few feet at each end. Behind it might have stood,

in two ranks, thirty-six men in all, of whom twenty, ten of

each rank, might have been able to fire through the embrasures

and over the ends, while the other sixteen would have been

better employed elsewhere.

It was conspicuous from its height and position, and the

enemy, seeing it from below, might easily have imagined it

more formidable than it was; but how could 3000 men be

employed in attacking, or a battalion such as the Coldstreams

in defending it ? Sixty men would have been an ample number

wherewith to assail it. As for the intrenchments on each side

of the road, a common bank and ditch, such as those which

generally border our fields, would have been incomparably

stronger for defence. Yet Todleben speaks of this

useless mound, and these insignificant banks, as " the enemy's

works," and another Russian writer says, " in spite of the

accumulated forces of the enemy, our columns succeeded in

occupying his batteries and fortifications.*

The truth is that few battlefields have been so devoid of

obstacles of this kind as that of Inkerman. The difficulties of

the attack lay in the hindrance which the coppice and crags

opposed to regulated advances and deployments, though, on

the other hand, these objects afforded to the enemy the not

inconsiderable advantage of sheltering his skirmishers.

Ardent Interest on the Home Front

Those who were children at the time of the Crimean

War can scarcely realise how ardent, how anxious, how

absorbing was the interest which the nation felt for the actors

in that distant field, insomuch that Mr Bright, theoretically a

man of peace, publicly said he believed there were thousands

in England who only laid their heads on their pillows at night

to dream of their brethren in the Crimea.

This feeling reached its climax with the news of

Inkerman, and it was not, nor indeed could it be, in excess of

the magnitude of the stake which depended on the issue of that

battle. The defeat of that slender Division on its ridge would

have carried with it consequences absolutely tremendous. The

Russians, arriving on the Upland, where the ground was bare,

and the slopes no longer against them, would have interposed

an army in order of battle between our trenches and Bosquet's corps.

As they moved on, disposing by their mere impetus of any

disjointed attempts to oppose thern, they would have reached

a hand to Gortschakoff on the one side, to the garrison of

Sebastopol on the other, till the reunited Russian Army,

extended across the Chersonese, would have found on those

wide plains a fair field for its great masses of cavalry and

artillery. To the Allies, having behind them only the sea-

cliffs, or the declivities leading to their narrow harbours,

defeat would have been absolute and ruinous; and behind such

defeat lay national degradation. On the other hand, when the

long crisis of the day was past, the fate of Sebastopol was

already decided. It is true that our misfortunes grew

darker and darker, that six weeks afterwards most of the

horses that charged at Balaklava. were rotting in a sea of mud,

most of the men who fought at Inkerman filling hospitals at

Scutari, or graves on the plain. Any history of the war would

be incomplete that failed to record, as a main and

characteristic feature of it, the extraordinary misery which the

besieging armies endured. Nevertheless, when Inkerman had

proved that the Russians could not beat us in battle, we were

sure to win, because it was impossible for us to embark in

presence of the enemy. We could do nothing else but

keep our hold; and, keeping it, it was matter of demonstration

that the Powers which held command of the sea must prevail

over the Power whose theatre of war was separated from its

resources by roadless deserts. Such were the consequences

which hung in the balance each time that the

Russian columns came crowding on, while their long lines of

artillery swept the ridge; and it is not amiss that the nation,

which sometimes gives its praise so cheaply, should be

reminded how much it owed that day to the steadfast men of

Inkerman.

Chapter VIII: The Hurricane and the Winter

When the Czar Nicholas received the news of the battle

of the Alma, he was, Kinglake tells us, terribly agitated. A

burst of rage was followed by a period, profound dejection,

when for days he lay on his bed taking no food, silent and unapproachable.

When the Czar Nicholas received the news of the battle

of the Alma, he was, Kinglake tells us, terribly agitated. A

burst of rage was followed by a period, profound dejection,

when for days he lay on his bed taking no food, silent and unapproachable.

(* Kinglake says this column was composed of sailors, and

therefore not included in the numbers of the army.)

"When, without stratagem,

But in plain shock, and even

play of battle,

Was ever known so great and

little loss,

On one part and on th' other? Take it,

God,

For it is only thine!"(* It is just possible that these writers may have supposed that some of the works placed on that ground long afterwards, were there at the time of the battle.)

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com