Jumbo Map: Crimea (extremely slow: 498K)

Thus it was as completely an unknown country to the

chiefs of the Allied armies as it had been to Jason and his

Argonauts when they voyaged thither in search of the Golden

Fleece. It was known to contain a great harbour, and a city with

docks, fortifications, and arsenal ; but the strength and

resources of the enemy who would oppose us, the nature of

the fortifications, and even the topography, except what the

map could imperfectly show, lay much in the regions of pure

speculation.

It was believed, however, that any Russian force there

must be inferior to that of the Allies, that the country would

offer no serious impediments to the march, and that, with the

defeat of the defensive army, the place would not long resist

the means of attack which would be brought to bear on it.

There was no thought of a protracted siege; a landing, a march,

a battle, and, after some delay for a preliminary bombardment,

an assault, were all that made part of the programme,

These anticipations were by no means so ill-founded

as, after the many contradictions by the event, they were

judged to have been. It was unlikely that a large Russian army

should be permanently kept in a spot not easy of approach by

land, and where its supply would be difficult, at a time when

Sebastopol was not imminently threatened ; and, since the

sudden cessation of operations on the Danube, there had been

little time for preparation against so formidable an attack as was

now impending. The command of the sea conferred on the

assailants inestimable advantages, and there was very fair

reason to expect that, long before Russia could bring her huge

numbers to bear, the conflict would be decided in closed lists

by the armies which should at first enter them. In any case, it

would have been very difficult to point to any more vulnerable

spot on Russian territory.

It must not, however, be thought that no siege of

Sebastopol was contemplated. Immediately after the Russians

retreated from the Danube, the Duke of Newcastle, Secretary

for War, wrote thus to the Commander of the British Forces, on

the 29th June 1854:

"The difficulties of the siege of Sebastopol appear to

Her Majesty's Government to be more likely to increase than

diminish by delay; and as there is no prospect of a safe and

honourable peace until the fortress is reduced, and the fleet

taken or destroyed, it is, on all accounts, most important that

nothing but insuperable impediments, such as the want of

ample preparations by either army, or the possession by Russia

of a force in the Crimea greatly outnumbering that which can be

brought against it, should be allowed to prevent the early

decision to undertake these operations. . . .

"It is probable that a large part of the Russian army

now retreating from the Turkish territory may be poured into

the Crimea to reinforce Sebastopol. If orders to this effect have

not already been given, it is further probable that such a

measure would be adopted as soon as it is known that the

Allied armies are in motion to commence active hostilities. As

all communications by sea are now in the hands of the Allied

Powers, it becomes of importance to endeavour to cut off all

communication by land between the Crimea and the other parts

of the Russian dominions." This despatch had been preceded by a private letter

containing this passage:

To Siege

A siege, then, was in the programme, but it is certain

that even a probability that it would last through the winter

would have put an end to the project.

While awaiting embarkation, the troops were employed

in making fascines and gabions for the siege works, the

material for which, abundantly supplied by the woods around

them, might not be found on the plains before Sebastopol ; and

great quantities of these were collected, ready for conveyance, on the south side of

Varna Bay.

It was at this time, while the armies were expecting to

begin the enterprise, that the cholera broke out among them.

Cases had occurred among the French troops while on the

voyage from Marseilles; the pest followed them to their camps,

and late in July it reached the British army. Out of three French

divisions, it destroyed or disabled io,ooo men, and our own

regiments in Bulgaria lost between five and six hundred. It then

attacked the fleets, which put to sea in hopes of thus baffling it,

but it pursued them, and reduced some ships almost to

helplessness. This was a main reason, among others, why the

stroke, which could not be dealt too swiftly, was delayed.

Meanwhile the preparations went on. In order that the

guns might be available immediately on landing, it was

desirable that they should be conveyed complete as for action,

and, to this end, boats, united in pairs, were fitted with

platforms bearing the guns ready mounted on their carriages;

and steamers were bought and chartered for the transport of

other material. And now the naval resources of England

showed forth in their superiority.

The French, in default of sufficient transport, crowded

their war-ships with troops, thus unfitting them for battle; so

did the Turks; while the sea was covered with the small sailing-vessels of both loaded with material. But in one great compact

flotilla of transports, in which the steamers were numerous

enough to lend the propelling power to all, a British force, of all

arms, namely, four divisions of infantry, the Light Brigade of

cavalry and sixty guns, with all that was necessary to fight a

battle, was embarked; and our warships, thus preserving all

their efficiency, were left in condition to engage the enemy's

should they issue from Sebastopol.

It was at Varna that the huge multitudinous business of

embarkation went on. Piers had been improvised by the

engineers, but of course the operation was accomplished under

difficulties vastly greater than would have been met with in

home ports. The troops moved down slowly from their camps ;

the poison in the air caused a general sickliness, and the men

were so enfeebled that their knapsacks were borne for them on

packhorses during even a short march of five or six miles, all

they could at once accomplish. As they were embarked,

they sailed for the general rendezvous in the Bay of Balchick,

about fifteen miles north of Varna. The mysterious scourge still

pursued them on board ship, and added a horrible feature to

the period of detention, for the corpses, sunk with shot at their

feet, after a time rose to the surface, and floated upright, breast

high, among the ships, the swollen features pressing out the

blankets or hammocks which enwrapped them.

After all were assembled, an adverse wind still delayed

them; but on the 7th September the whole armament got under

weigh in fine weather. Each British merchant steamer wheeled

round till in position to attach the tow-rope to a sailing

transport (most of these were East Indiamen of the largest

class), and then again wheeled till the ship in rear attached

itself to a second; then all wheeled into their destined positions for the voyage.

They were formed in five columns, each of thirty vessels,

and each distinguished by a separate flag; and the five

columns carried the four divisions of infantry, with their

artillery, namely, the Light, the First, Second, and Third,

complete, and the Light Brigade of cavalry. Few sights more

beautiful could be seen than the advance, and the maneuvres

which preceded it, of this orderly array of ships, all among the

largest in existence, on the calm blue waters, under the bright

sky. The French and Turks, notwithstanding the use of their

men-of-war for transport, were unable to carry any cavalry.

British Flotilla

Our flotilla was commanded and escorted by Admiral Sir

Edmund Lyons in the Agamemnon. Our naval Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Dundas, directed the British Force that was held

ready to engage the enemy, including ten line-of-battle ships,

two screw-steamers, two fifty-gun frigates, and thirteen smaller

steamers carrying powerful guns. The French fleet numbered

fifteen line-of-battle ships and ten or twelve war-steamers, and

the Turkish eight line-of-battle ships and three war-steamers.

The Russian fleet had, since the first entry of the Allies

into the Black Sea, remained in the fortified harbour of

Sebastopol. It consisted of fifteen sailing line-of-battle ships,

some frigates and brigs, one powerful steamer, the Vladimir,

and eleven of a lighter class. Considering the encumbered

condition of the French and Turkish squadrons, it seems clear

that if, with a fair wind and good officers, the Russian

armament had issued from its shelter, it might in a bold attack

(though of course at heavy cost) have inflicted tremendous

havoc on the transports and troops.

British Land OOB

It is to be noted that the Fourth Division of infantry,

the Heavy Brigade of cavalry, and five or six thousand baggage

horses belonging to the English army, were still at Varna

awaiting embarkation, and the siege train was also there in the

ships which had brought it from England. Of these the greater

part of the Fourth Division was immediately embarked, and

landed in the Crimea in time to advance with the army.

Our five infantry divisions were formed each of two

brigades, each brigade of three regiments, and each division

numbered about 5000.

The First Division was commanded by the Duke of

Cambridge, and was formed of the brigade of Guards, viz., a

battalion each of the Grenadiers, Scots Guards, and Coldstream,

under General Bentinck; and the 42d, 79th, and 93d

Highlanders, under Sir Colin Campbell; with two field batteries.

The Second Division was commanded by Sir De Lacy

Evans, and composed of the brigades of Pennefather, 3oth,

55th, 95th, and Adams, 41st, 47th, 49th; with two field

batteries.

The Third Division was under Sir Richard England,

with Brigadiers Campbell and Eyre, 1st, 38th, 50th; 4th, 28th,

44th regiments; with two field batteries.

The Fourth Division was at first incomplete, its 46th

and 57th regiments being still en route. It was under Sir George

Cathcart, having the 20th, 21st, 63d, 68th

regiments, and the first battalion of the Rifle Brigade; with one

field battery.

The Light Division was commanded by Sir George

Brown, with the 7th, 23d, and 33d, under General Codrington;

and the 19th, 77th, and 88th, under General Buller; also the

second battalion of the Rifle Brigade; with one troop of horse

artillery, and one field battery.

The Light Brigade of cavalry, under Lord Cardigan,

included the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons, the 8th and 11th

Hussars, and the 17th Lancers; with one troop of horse

artillery.

Commanders

Sir George Brown had distinguished himself in the

Peninsula as an officer of the famous Light Divisionthe reason,

perhaps, for now giving him the command of it-and had been

severely wounded at Bladensburg; since when his military life,

like his chiefs, had been passed chiefly in office work. He had

held many

posts, including that of Adjutant-General at the Horse Guards.

Sir De Lacy Evans had a brilliant record from the

Peninsular, American, and Waterloo campaigns, and had been

Commander of the British Legion in Spain in two very

honourable campaigns and many battles.

Sir George Cathcart had in his youth, as aide-de-camp

to his father, British Commissioner with the Russian Army,

been present at the chief battles in 1813. He was also on

Wellington's staff at Quatre Bras and Waterloo. He was

favourably known as the writer of commentaries on the

campaigns of 1812 and 1813 in Russia and Germany; he had

commanded various regiments of cavalry and infantry; and, as

Governor of the Cape, had recently conducted successful

campaigns against the Kaffirs and the Basutos. On these

grounds, his reputation stood so high that a "dormant

commission" had been given to him, entitling him to command

the army in case Lord Raglan should cease to do so.

Of the Brigadier-Generals the best known was Sir Colin

Campbell, who had established a great reputation as a

commander of large forces in our Indian wars, after very

honourable service in the Peninsula.

Most of the French generals had seen much active

service in Algeria. St Arnaud was a gallant man, experienced in

the warfare suited to that country, but frothy and vainglorious

in a notable degree-and much too anxious to represent himself

as taking the chief part to be a comfortable ally.

Though part of the English army had seen service

in India, though a large portion of the French troops had made

campaigns in Algeria, and though the Russians had for years

carried on a desultory war in Circassia, yet the long European

peace had left them all with little except a traditional knowledge

of civilised war.

No change of method had taken place since the

Napoleonic era. But the British and French had both

abandoned the musket for the rifle, ours being the Mini6; both

it and the French arm were muzzleloaders; some Russian

regiments had a rifle, but a, large proportion of them were still

armed with the old brass-bound musket which had served them

throughout the century ; the artillery also of all remained as before.

As the fleets sailed eastward from Varna across the

Black Sea, their course was crossed at right angles by the

coast on which they were to land, and of which they might

almost be said to know as little as knight-errants, heroes of the

romances beloved by Don Quixote, knew of the dim, enchanted

region where, amid vague perils, and trusting much to happy

chance, they were to seek and destroy some predatory giant.

Crimean Geography

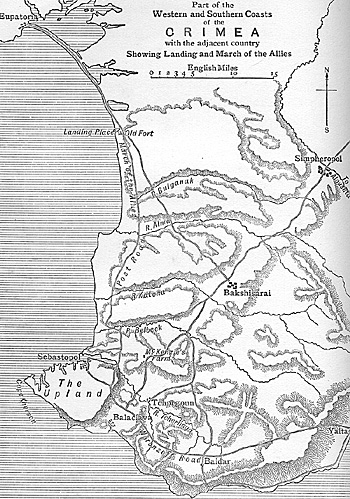

Crim Tartary, better known now as the Crimea, forms

part of the Government of Taurida, a province of Southern

Russia. From the coast of the Euxine it stretches southward, as

an extensive peninsula, into the midst of that sea. Its neck is

the Isthmus of Perekop, five miles wide, and its length from

thence to Balaklava at its southern end is, in direct line, 120

miles.

All the northern and middle portion is a flat and and

steppe, where are sprinkled at wide intervals small villages

inhabited by Tartars, whose possessions are flocks and herds;

but the remaining and southern end of the peninsula is

different indeed in aspect, and in climate. Here begins a

mountain region sheltering from the northern blasts the slopes

and hollows, the lesser hills of which, covered with pine and

oak, enclose valleys of bounteous fertility. Multitudes of wild

flowers spring up amid the tall grass; the fig, the olive, the

pomegranate and the orange flourish, and the vine is cultivated

with success on the southern slopes.

The seaward end runs out into capes resting upon high

cliffs, and is indented on its western side by the deep and

sheltered harbour of Sebastopol, which, as the chief and

indeed only large and safe harbour of the Black Sea, had by the

work of generations been converted into a great arsenal and

dockyard, defended towards the sea by strong forts, and

affording ample anchorage for the Black Sea fleet, and around

these works had sprung up a city. The area of the whole

peninsula is nearly twice that of Yorkshire, and its population

at the time of the invasion numbered something short of

200,000.

Going along the road from Sebastopol to Perekop, the

first considerable town reached, sixteen miles distant, is

Bakshisarai, "the Garden Pavilion," and in another sixteen

miles, where the road quits the hills for the steppe, is

Simpheropol, the nominal capital. The part of the country with

which the reader has at present to do is included in a parallelo.

gram, one side of which is a line outside the western coast

from Eupatoria to the level of Balaklava, and the

opposite side passes through the hill region, south from

Simpheropol to the sea.

In this region the mountains have subsided into hill

ranges of some 400 feet high, and through these the watershed

pours five streams flowing westward into the Black Sea, all of

which formed features in the campaign. The first of these is the

muddy rivulet called the Bulganak; seven miles south of it is

the valley of the Alma (Apple River) ; another space of seven

miles divides the Alma from the Katcha; four miles further the

Belbek is reached; and five miles from that the Tchernaya,

northwesterly in its course, flows into and forms the head of

the harbour of Sebastopol.

The distance from Varna to Eupatoria is about 300 miles.

The armament arrived on the 9th at the rendezvous first

assigned, "forty miles west of Cape Tarkan." It remained

anchored there throughout the 10th, while Lord Raglan and

General Canrobert, with the Commanding Engineer, Sir John

Burgoyne, and other English and French officers, naval and

military, reconnoitered the coast for a landing-place, and

observed its character throughout.

At dawn, in a swift steamer, the Caradoc, escorted by

the Agamemnon, they were off Sebastopol, and could look

through the entrance of the inlet upon the forts, the ships, and

the city; then, rounding Cape Kherson, they passed the cliffs

on which stood the olateau destined to bear the camps of the

besiegers, and arrived off the inlet of Balaklava, deep down

between its two ancient high-perched forts. Then, turning back

north, they took note of the rivers already enumerated, from the

Belbek to the Bulganak, and the coast thence to Eupatoria,

when the space for the landing was fixed on, south of that

town, in Kalamita Bay. All the 11th and 12th the Turkish and

French fleets, great part of which was not propelled, as was

ours, by steam, were drawing together, and on the 13th nearly

all were opposite the beach, while those still at sea were coming

on with a fair wind.

The considerations which had been main elements in

the question of the selection of a point of disembarkation were,

first, a space sufficient for the armies to land together, and in

full communication with each other; and secondly, that the

ground should be such as the fire of the ships could protect

from the possible enterprises of the enemy. Ship's guns are so

formidable in size and range that no batteries capable of rapid

motion can hope to contend with them.

No ground fulfilling these conditions was found on the

southern coast, where the cliffs stand up steep and high out of

the water, nor did the mouths of the rivers afford the necessary

advantages. On the other hand, the western coast north of

Sebastopol offered no harbour of which the armies could make

a secure base, or even a temporary depot; while, south of

Sebastopol, the inlet of Balaklava, though small, was deep and

well-sheltered, where large steamers could unload close to the

shore, and the small bay of Kamiesch was capable of being

made a base. These facts will tend to throw light on some

questions raised during the progress of the war.

The piece of beach selected to land on, five or six

miles north of the Bulganak, was very happily adapted for the purpose.

Two small lakes at the foot of the sea-banks are

separated from the sea by strips of beach, and from these

strips roads went up the banks. Thus, when the troops were

landed here, no attack could be made on them (by night, let us

suppose) except bypenetrating into the narrow and easily

defended space between the lakes and the sea; while, on the

other hand, full facilities existed for their movement to the

plains above.

Here the disembarkation, quite unopposed, began on

the 14th, the French and Turks landing about two miles lower

down the coast, on a similar strip. In the afternoon a ground

swell arose, to a degree so violent that many boats were hurled

on the strand, and several rafts were dashed to pieces, the

troops, drenched with rain, making fires of the fragments. Next

day the surf abated, but it was not till the 18th that the whole

of the forces were landed, and in condition to advance.

The Fourth Division having arrived and landed, the

British force numbered about 26,000 infantry, sixty guns, and

the Light Brigade of cavalry, about 1000 sabres. The French

had 28,000 infantry, and the Turks 7000, with sixty-eight guns,

but with no cavalry. In order that the men might march lightly,

especially when so many were still low in strength from the

effects of the atmosphere, the knapsacks of the British were left

on board ship, the more indispensable articles being taken from

them and carried by the soldier, wrapt in the blanket which was

to cover him at night.

No tents were landed except for the sick and for general

officers. Except such part of the packhorses as could be

conveyed in the flotilla, there was no transport landed, but

some convoys of the enemy were intercepted, and a number of

country vehicles were procured from the Tartars. In this way

350 arabas (the wagons of the country, a rude framework of

poles surmounting the axle) were collected and a thousand

cattle and sheep, with poultry, barley, fruit, and vegetables.

Chapter III: Battle of the Alma

The land which the armies were about to invade was that

known to the ancients as the Tauric Chersonese. It was quite

beyond the range of the ordinary tourist, it led to nowhere, and

had little to tempt curiosity.

The land which the armies were about to invade was that

known to the ancients as the Tauric Chersonese. It was quite

beyond the range of the ordinary tourist, it led to nowhere, and

had little to tempt curiosity.

"I have to instruct your Lordship to concert

measures for the siege of Sebastopol, unless, with the

information in your possession, but at present unknown in this

country, you should be decidedly of opinion that it could not

be undertaken with a reasonable prospect of success. The

confidence with which Her Majesty placed under your

command the gallant army now in Turkey is unabated, and if,

upon mature reflection, you should consider that the united

strength of the two armies is insufficient for this undertaking,

you are not to be precluded from the exercise of the discretion

originally vested in you, though Her Majesty's Government will

learn with regret that an attack from which such important

consequences are anticipated must be any longer delayed.

"The Cabinet is unanimously of opinion that, unless

you and Marshal St Arnaud feel that you are not sufficiently

prepared, you should lay siege to Sebastopol, as we are more

than ever convinced that, without the reduction of this fortress,

and the capture of the Russian fleet, it will be impossible to

conclude an honourable and safe peace. The Emperor of the

French has expressed his entire concurrence in this opinion,

and, I believe, has written privately to the Marshal to that

effect."

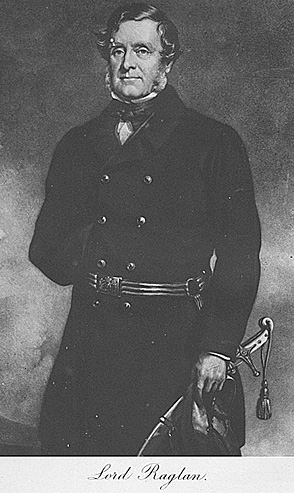

Lord Raglan, Commander of the English Army, was sixty-six years old. He had served on Wellington's staff, and lost his

arm at Waterloo. Since those days his sole military experience

had been in the office of Military Secretary at the Horse

Guards. He was so far well acquainted with military business,

but he had never held any command, and while no opportunity

had been afforded to him of directing troops in war, his life, for

forty years, had been no adequate preparation for it. But he

was a courteous, dignified, and amiable man, and his qualities

and rank were such as might well be of advantage in preserving

relations with our Allies.

Lord Raglan, Commander of the English Army, was sixty-six years old. He had served on Wellington's staff, and lost his

arm at Waterloo. Since those days his sole military experience

had been in the office of Military Secretary at the Horse

Guards. He was so far well acquainted with military business,

but he had never held any command, and while no opportunity

had been afforded to him of directing troops in war, his life, for

forty years, had been no adequate preparation for it. But he

was a courteous, dignified, and amiable man, and his qualities

and rank were such as might well be of advantage in preserving

relations with our Allies.

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com