Jumbo Map: Battle of Alma (extremely slow: 478K)

The four French divisions were ranged in lozenge form, the apex

heading south for Sebastopol, the four points marked each by

a division with its guns; and in the space thus enclosed were

the Turks, and the convoy of provisions, ammunition, and baggage.

The British were formed in two columns of divisions, that

next the French of the Second Division followed by the Third;

the other of the Light Division followed by the First and

Fourth; the batteries on the right of their respective divisions.

The formation of the divisions was that of double companies

from the centre, giving them the means of forming with

readiness either to the front or the left flank, which was also

the object of placing three of the five divisions in the left column.

If the Russians, after leaving a sufficient garrison in

Sebastopol, were to keep an army in the field, it might, from its

natural line of communication with Southern Russia, namely,

the road thither by Bakshisarai and Simpheropol, assume a

front at right angles to the front of the Allies, and advancing

thus, might attack either their flank or rear without risk to its

own. On this account, also, the Cavalry Brigade was divided,

two of its regiments covering the front, the other two the left

flank, while the fifth closed the rear.

If the Russians were to threaten that flank, the three

divisions of our left column would be the first to confront

them, with the other two in second line, while the French and

Turks must come up on their right, or left, or both, according to

the direction of the Russian attack, and with fair chance, on

those open plains, of meeting it in time, and also, if forced to retreat with their backs to the sea, they might expect effectual

support from their ships. But, at the best, persistent attacks on

this side by the Russians, with such a wide space to maneuvre

on at pleasure, and with cavalry in superior force (as, with our

deficiency in that arm, it was certain to be) would greatly,

perhaps decisively, embarrass our advance unless we should

succeed in inflicting on the enemy a crushing defeat.

The combined armies, then, were moving, in sufficiently

compact formation, straight for Sebastopol, about twenty-five

miles distant from the starting point of the British ; through

their front ran the post-road to that city from Eupatoria; but

roads were needless, for the

ground was everywhere smooth, firm, grassy, and quite

unenclosed. In rear of the divisions moved the cattle, sheep, the

close array of arabas, and the pack-mules with the reserve

ammunition, while the cavalry regiment in rear kept all in motion.

In this order the Bulganak, an insignificant sluggish stream, was

reached early in the afternoon.

First Contact

It was while our divisions were crossing its bridge that they

first saw the enemy. A force of the three arms, about 2000

cavalry, 6000 infantry, and two batteries of artillery, was drawn

up among the hills, at some distance beyond the stream ;

insufficient for a battle, but capable of an action with an

advanced guard. It appeared to have been brought there only

to effect an armed reconnaissance, for after a short and distant

exchange of shots with our foremost batteries, with some

trifling loss on either side, it retired without any noteworthy

collision of foot or horse.

The army thereupon bivouacked on the stream (for the sake

of water), with its front some hundred yards on the further

bank; the British right wing parallel to the stream, and the left

thrown back to the rivulet, in case of an attack on that side. But

it passed the night unmolested.

The next morning, the 20th, the troops were under arms

early, but did not move for some time. Marshal St Arnaud,

returning from a visit to Lord Raglan, passed along our front; a

tall, thin, sharp-visaged man, reduced by illness, but alert and

soldier-like, and manifestly much pleased as he saluted our

ranks in return for the cheers with which they greeted him. In

less than ten days he was a dead man.

Between nine and ten o'clock the army moved forward,

surmounting a succession of grassy ridges. It was well known

that we were to try conclusions with the Russians that day.

About noon a steamer, coasting along on our flank, began to

fire towards the land, just where a sharp, steep cliff ended the

shore, and where, in fact, was the mouth of the Alma. When

the British surmounted the next ridge, they looked down on the

arena of battle.

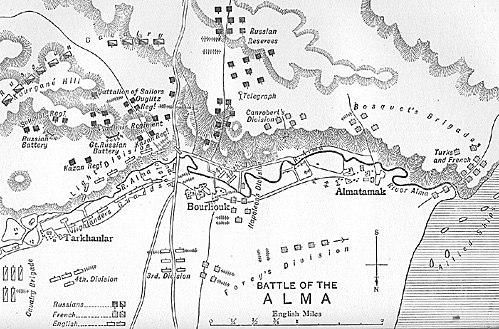

The valley of the Alma lay before them, at the foot of a

smooth, sloping plain. The river, as it flows at the foot of this

plain, makes somewhat of an angle, enclosing the Allies ; and

the apex just marks the junction of the French left with the

English right. just within the apex is the village of Bourliouk,

and noting that as the place where the two Allied armies

touched, the share of each in the battle becomes clear.

The ground on the Russian bank was, as befitted a

defensive position, much more difficult and commanding than

on the other. Beginning at the sea, for more than a mile and a

half thence up the stream, there rises close to it a perpendicular

rocky wall, as if the sea-cliff were bent backward. Then comes

another mile where the cliffs have receded somewhat, and

subsided into hills, still steep and difficult, though not

forbidding ascent. Near the mouth of the Alma the stream was

fordable, and from thence a path led up the cliff.

Three-quarters of a mile up the stream from its mouth

there is on the Allies' bank the village of Alma Tamack; and

opposite this a cleft in the cliff allows of a road

practicable for guns, which ascends the heights. A mile further

up is a farm, opposite which the cliff has subsided and

receded, and here is another road. Finally, at another half mile

up the stream, a few hundred yards to the right of the village of

Bourliouk, where, on the Russian side, the hills have still

receded and become more practicable, another road crosses,

ascending the heights to a telegraph tower.

Everywhere, the hills, whether standing up in cliffs, as near

the sea, or receding from the stream, were the buttresses which

supported on their tops a high plain stretching away towards

the next river that crossed our line of march on Sebastopol.

The part of the stream thus described marks the front

of the French and Turks, who may be said to have faced

south-south-west.

The other face of the angle made by the stream marks

the British front, which may be said to have faced south-south-

east. And now the character of the Russian side of the river

changes materially. Here the crest line has receded much

farther back, and the ground is easy of ascent for all arms. Just

opposite the centre of the British front it shoots up to a

pinnacle, called the Kourgane Hill, from the sides of which

long, smooth, wide slopes descend to the river. The one of

these which chiefly concerns us, that on our right front, is

broken in its even descent from the summit by a high knoll

surmounted by a terrace, at some hundred yards from the river.

Remembering that ground is good for defence, not so much

because of the difficulties it opposes to movement, as because

of the facilities it affords for bringing the fire of the defenders

to bear on the assailants, and for counter-attacks, it will be

understood why Menschikoff had occupied this part of his line

most strongly both with infantry and artillery.

The great post-road from Eupatoria to Sebastopol, on

each side of which the British had been marching, passes the

river by a bridge a little to the left of the apex of the angle

formed by the stream, and then ascends to the plateau, through

the hollow between the Telegraph Hill on the right and the

Kourgan6 Hill on the left. There was good reason for

Menschikoff to take position across the road. But in doing so

he had of course to consider what extent of ground was suited

to his force, very inferior to that of the Allies.

Bearing in mind the inaccessible nature of the cliffs, and

also that troops ascending them would be very near the edge

of the precipitous face above the sea-remembering too that the

ships, as he presently found, could throw their big projectiles

on to that part of the ground-he massed the chief part of his

force about the Kourgane slopes, and nearly all the remainder

between the Sebastopol road and the Telegraph Hill.

And this arrangement would have been so far

unimpeachable had he done what he easily could have done to

debar the enemy from the roads leading up the cliffs, either by

breaking them up, or by placing works at the points where they

reached the plateau. With the aid of other fieldworks on his

front and flanks he might have justly considered himself as

occupying, despite his inferior numbers, a strong position for

the direct defence of Sebastopol. But no such means were taken of adding to the

strength of the ground, for the two bits of trench work made

by him were not intended as defences.

A Pause

A halt of some length was made by the Allies on

coming in sight of the enemy, while Lord Raglan and St

Arnaud, moving out to the front, concerted the general order of

the attack. When the advance was ordered, about one o'clock,

it was begun by Bosquet's division, which was next the sea,

and faced the cliffs. After laying down their knapsacks, one of

his brigades crossed the Alma near its mouth, and ascended

the path there, followed by the Turks ; and the other entered

the. road through the cliff opposite Alma Tamack, by which

passed also the divisional artillery.

At the same time French ships near the mouth of the

stream threw their projectiles on to the plateau, the surface of

which they could see. The remainder of the French forces

followed in a line of columns at some considerable distance in

rear of Bosquet. Next to his division was Canrobert's, which

entered the road opposite the farm, and debouched on the

plateau nearly a mile west of the Telegraph; but he was obliged

to send his guns by the road followed by Bosquet's left

brigade. Next to Canrobert's came Prince Napoleon's division,

and behind both was Forey's in second line.

All these troops then were directed on the right face of

the angle formed by the stream, and all were on the right of the

post-road to Sebastopol. The ground may be at once cleared

for the battle by saying that Bosquet's right brigade and the

Turks, passing at the mouth of the stream. found themselves far

from the enemy, on whom they never fired a shot; and his other

brigade was a mile west of Canrobert's division, which, it has

been said, was nearly a mile from the Telegraph, while all its

artillery was following Bosquet's left brigade, Prince Napoleon's

division bore directly on the ground immediately around the

Telegraph. All this makes it plain that a little engineering

science on the part of Menschikoff would have almost

neutralised the action of the French and Turks in the battle. As

it was, the chief result achieved by St Arnaud was that he

gained a position threatening Menschikoffs left flank at the

moment when his front was assailed by the English.

The British divisions moved down abreast of the

French, at first in column formation, the Second Division on the

right, the Light Division on the left, in first line; the Second

followed by the Third, the Light by the First, in second line,

and the Fourth in echelon in rear of the left. Beyond the left

moved four regiments of the Light Brigade, while the remaining

one closed the rear. As they advanced, the Russian forces

became more clearly discernible, as did also the ground our line

was to occupy.

It was marked on the right by the village of Bourliouk,

already mentioned, and on the left, about two miles up the

stream, by the village of Tarkhanlar, to which, however, the left

of our infantry did not quite attain. Between the two were

gardens and vineyards, enclosed by low stone walls,

stretching down to the stream, which proved fordable nearly

throughout. Right opposite our centre, as we moved, was the

slope of the Kourgane Hill, with its terraced knoll a few hundred

yards from the river, on which appeared an earthwork of some

kind, with twelve or fourteen guns, some of them bearing on

the post-road, some directly on our front, some on our right

wing. and thus sweeping our whole front.

A thousand yards from this battery, and facing our left,

another earthwork with guns was visible. As already said,

these works were not intended for defence, for they were easily

surmounted, being banks of earth only two or three feet high,

so that the guns looked over them; they were probably

intended to prevent the pieces from running down the slope,

and also might afford some slight shelter to the gunners.

Behind the battery on the Kourgane, and on its flanks, the

Russian battalions were thickly posted, their front extending to

the battery facing our left; and on the other flank they were

massed on the knolls close to the post-road.

The columns in reserve were higher up on the slopes,

where also were drawn up the 3400 cavalry of Menschikoff's

army. Besides the battery on the knoll, he had on this part of

the field nine field batteries (the Russian battery is of eight

guns), of which one was in the earthwork on his right, another

supported the twelve-gun battery, two in reserve on the upper

slope, two across the post road, bearing on the bridge, and

three attached to the cavalry. The force confronting the English

may be taken as 21,000 infantry, 3000 cavalry, and eighty-four

guns; those opposing the French as 12,000 infantry, 400

cavalry, and thirty-six guns: making the totals of Menschikoff's

army 33,000 infantry, 3400 cavalry and 120 guns. Part of the

British Fourth Division had been left behind at the place of

disembarkation to clear the beach, and did not arrive till after

the battle.

Our force engaged was 23,000 Infantry, 1000 cavalry, and

sixty guns. The French and Turks together numbered about

35,000 infantry, with sixty-eight guns. Deducting the column

that passed the Alma at its mouth, they had 25,000 infantry,

and sixty-eight guns; these when brought to bear would of

course overwhelm the force opposed to them, which, moreover,

only came by degrees on the French part of the field, where no

attack had been provided for by the Russians. It is impossible,

therefore, that the French could have met with any very strong

opposition.

Skirmishers Advance

As the skirmishers on our right approached Bourliouk

they were met by the fire of Russian light troops and light guns

in the village; while the skirmishers in front of the Light

Division (four companies of its rifle battalion), encountered a

large number of the enemy's skirmishers in the vineyards; but,

as our columns advanced, these retired across the stream, first

setting fire to Bourliouk, the conflagration of which was a

notable incident of the battle.

It was now that the twelve-gun battery on the

Kourgane Hill gave our people a taste of its quality; shot and

shell of a size far greater than that of fieldartillery, began to tear

the ground, and to burst in the air. The Light and Second

Divisions began thereupon to deploy; but our right was much

too close upon the French, and a great deal of marching and

countermarching now took place, without mending the fault,

for too little ground was taken, and our troops were crowded in

their advance to a most damaging degree.

The delay was not accidental, however, but was according

to the plan, in pursuance of which the advance against the

front of the strongly occupied part of the position was only to

take place when Bosquet's movement against the left should

begin to take effect. His voltigeurs, and afterwards those of

Canrobert, had been seen swarming up the heights, and some

guns (Bosquet's twelve) had been heard, along with the

Russian batteries opposing them. But, as already said, the

French artillery had all to advance by one road; the process

was slow, and Canrobert's main body of infantry, as well as

Prince Napoleon's division, waited for the support of the guns-

hence the delay. Kinglake says that, while their movement was

still incomplete, a French staff-officer came from St Arnaud to

ask Lord Raglan to advance. The order to attack was thereupon

given to the Second and the Light Divisions.

Having issued this command, the English general took

a course too extraordinary to remain unnoticed. Accompanied

by some of his staff, he rode round the right of the burning

village, and descending to the Alma, crossed it by a ford close

to the left of the French Army. Proceeding up the opposite

bank, he reached a knoll between the Telegraph Hill and the

post-road, from whence he looked from a distance, which was

at the moment beyond the effective range of field-artillery, upon

the flank of the Russian position on the Kourgane' Hill, and

also, on his right front, on the columns of the Russian reserves.

He was thus in the singular position for a. commander of

occupying, with a few officers, a point well within the enemy's

lines, and beyond the support, or even the knowledge, of any

of the rest of his army; and Kinglake, the historian, who

accompanied him in this excursion, and who records it with

applause, says, also, he was too far from the scene of the main

struggle on which his army had now entered to be able, for the

time, to direct the movements of his own troops.

It was fortunate, in these circumstances, that the

divisional commanders had so plain a task before them. On

receiving the order, the Second and Light Divisions had at once

begun their advance; but Evans's being delayed by the burning

village, and having to pass round both ends of it to the river,

Brown's, forming the left of our line, was the first to attack.

Passing the low wall of the vineyards which occupied this bank,

pushing before it the Russian skirmishers, and losing some men

as it went, it made its way, much disordered by the tangling

vines, to the stream, whose clear current was in most places

shallow, but in others formed pools where the men were in water

to their necks.

Wading through, they found themselves, at a very few

yards from the stream, standing beneath an almost

perpendicular bank about six feet high, in which the long slope

abruptly ended, and where they were for the moment out of the

view of the enemy's battery above them on the hill.

A pause was made here, ended by Sir George Brown

himself riding up the bank and calling on his regiments to

follow. The whole division thereupon gained the slope, and

began the attack--not in orderly lines, for, besides insufficiency of space, it was

impossible under such a fire as now assailed it to form these,

but with such attempts at lines as the men themselves,

instinctively seeking their own companies, succeeded in

making, that is to say, a line chiefly of groups and masses. But,

whenever they were able to form, our regiments attacked in a

two-deep line, according to our custom, and were met by the

Russians in deep columns, formed of two or more battalions, so

that the front of a British line was of greater extent than that of

the double or quadruple force in the enemy's column engaged

with it.

Three regiments of the Light Division, with one of the

Second Division, gallantly led by General Codrington, went

straight up the slope, their too dense front torn by the great

heavy battery, only three hundred yards in front of them, and

firing down a smooth natural glacis.

On our right of that battery the 7th regiment had become

engaged with a Russian column formed by the left wing of the

Kazan regiment, and numbering 1500 men; while the two left

regiments of our Light Division had been halted on the slope

near the river, because General Buller, perceiving a formation

and advance of infantry and cavalry on his left front, formed a

corresponding front to meet it.

The regiment of the Second Division (95th) which had

joined Codrington was one of four led by Evans himself across

the river near the bridge, and which then, bearing considerably

to their left, partly prolonged and partly supported the Light

Division, while his other two battalions (41st and 49th), under

General Adams, passing round the right of the burning village,

crossed by a ford below into the hollow space, garnished with

knolls, between the Telegraph and Kourgan6 Hills, where

stood part of the Russian left.

The First Division, formed in second line to the Light,

embraced much more ground, so that the brigade of Guards

extended from near the post-road to quite beyond the rear of

Codrington's brigade, while the Highlanders, forming abreast

of them, were prolonging the front of the army. After remaining

for some time, lying down in line during the advance of the

Light Division, the First Division followed it through the

vineyards and across the Alma.

Codrington's brigade continued its brisk advance, and

now occurred a singular event that was a turning point of the

battle, which was nothing less than the sudden retreat of the

great heavy battery which had been so formidable a feature of

the Russian position. This withdrawal was very discreditable.

Whether it was owing to the menacing aspect of the advancing

troops, or to anxiety to avoid the loss of guns (and Kinglake

says it was well known that such loss would draw down the

displeasure of the Czar), it was a disgrace to such a powerful

battery, so important to the battle, so surrounded with

supporting battalions, to save itself just when, by continuing

in action, it might cause heavy and perhaps decisive loss to the

enemy. It vanished with celerity just as Codrington's men were

touching the earthwork in front of it.

Cavalry horses, equipped with lasso harness, came up hastily, were

hooked on, and drew the guns away, except two which were captured.

Relieved from the tremendous stress of fire which had

poured such huge missiles, at such close quarters, through

their ranks, Codrington's regiments, after entering the

earthwork, lined the low parapet, and extended on both sides of

it. Those on the right were in some degree protected by the 7th,

still holding the left Kazan column fast; and on the left, by the

two battalions that had been held back there.

Facing Codrington were the four battalions of the

Vladimir regiment, 3000 strong, supported by the Ouglitz

regiment, of the same strength (though it never got down into

the conflict), and the right wing of the Kazan regiment; the

Vladimir was closely supported by the fire of the field battery,

already said to be in support of the great battery.

And had our attack been so ordered that the

supporting divisions were now taking part in it, the conflict,

assuming large proportions, might have drawn into its active

area the whole of the forces on both sides, and have issued in

a result more decisive than a mere victory. But the troops with

Codrington, without close support, seeing before and around

them fresh masses of the enemy, being a target for their guns,

and threatened by a great body of cavalry, gave way and

descended the hill.

On arriving at its foot the four regiments, and the four

companies of rifles, were less in number than when they went

up by forty-seven officers, fifty sergeants, and 800 rank and

file, killed and wounded; and, in addition, the 7th lost twelve

officers, and more than 200 men. But they had inflicted far

heavier losses on the enemy.

Had they but clung to the ground they held a few

moments longer, they would have received effectual support,

for the Guards, after gaining the farther bank of the stream in

good order, had already begun the ascent, and their centre

battalion, the Scots Fusiliers, was disordered and swept down

by the retreating troops, with a loss of eleven officers and 170

men. But the Grenadiers on its right, and the Coldstrearns on its

left, continued to advance in lines absolutely unbroken, except

where struck by the enemy's shot. Such French officers on

the hills on the right as, in an interval of inaction, were free to

observe what our troops were doing, spoke of this advance of

the Guards as something new to their minds, and very admirable.

Advance

At this time the whole of our troops were being

brought to bear on the position. The three regiments remaining

with Evans (55th, 30th, and 47th) had been engaged chiefly on

the left of the post-road, against the battalions and batteries

drawn up for its defence, and had undergone heavy losses. His

two other regiments (41st and 49th), which had moved to the

stream on the other side of Bourliouk, were towards the close

of the battle brought up to the knoll where Lord Raglan stood.

The Third Division was moving across the stream in

support, and on the left of the Guards the Highlanders were

advancing against the Russian right flank, while beyond them

again moved our Cavalry Brigade. It was, then, upon troops

shaken by heavy losses, and dispirited for the want of a forward impulse, that

our whole army was now closing.

Our artillery had also taken an effective share in the

fight. At first, till ground was gained on the further bank, some

batteries of the Light, Second, and First Divisions had, from the

space behind and around the burnt village, brought their fire to

bear on the men and guns defending the post-road, but as the

infantry advanced they began to cross the river. The battery of

the First Division, already in action, now passed at a shallow

ford just below the bridge, and going some way up the road,

ascended a knoll to the left, where it found itself on the right of

the 55th, and in full view of the field.

The guns had outstripped the gunners, who followed

on foot, and the gun first to arrive was loaded and fired by the

officers, who dismounted for the purpose. The rest of the

battery immediately came up, and its fire bore on and turned

back a heavy Russian column (the only one at that time within

view) which was descending the hill. Two batteries from other

divisions also came into action here, and on the ground where

Lord Raglan stood two guns, called up by him, had been so

placed as to bear on the flank of the batteries guarding the post-

road, causing them to retire, while the two troops of horse-

artillery, advancing with the cavalry on our left, were finally

directed on the masses still held in reserve by Menschikoff.

The two battalions of the Guards, with some men

rallied from the Scots battalion, went up the hill on each side of

the gap in their centre, and were met by the four battalions of

the Vladimir regiment, and the two Kazan battalions, much

shattered in the fight, which had hitherto been engaged with

the 7th. This new phase of the battle was not of long duration.

The columns could not stand before the close fire of the lines.

Moreover, at this moment the Highland regiments, after

receiving the badly aimed fire of the field-guns in the earthwork

on the flank (which then rapidly withdrew from the action), had

now approached the right of the Russian position. The brigade

was in echelon, the right battalion leading and already past the

earthwork defended by the Vladimir. This Russian regiment,

after undergoing heavy loss, still hotly assailed in front by the

Guards, and its rear threatened by the Highlanders, retreated to

its right rear towards the right Kazan column, upon which it

endeavoured to form, and both came under the fire of the

leading Highland regiment (42nd).

At the same time Campbell's other regiments attacked

the columns hitherto in reserve high up the Kourgane Hill.

These did not maintain the contest; the Russian forces all over

the position were quitting it. No attempt was made by their

cavalry or artillery on this side of the field to cover the retreat;

they seemed to have shifted for themselves, leaving the

infantry columns to make their way off the field, which they did

without panic, though shattered as they went by our most

advanced field batteries.

The English, moving over the whole field, from the

eastern slopes of the Kourgane on the extreme left to the

slopes of the Telegraph Hill now occupied by the French, once

more completed the connection of the Allied Forces. Lord

Raglan proposed to push the enemy in his retreat with the

untouched troops of the two armies; but the French Marshal

declined to join in that step, on the ground that his men had

divested themselves of their knapsacks before ascending the

heights, and that it was impossible to advance till they had

resumed possession of them. The leading English batteries

continued, however, to pursue the enemy with their fire for

some little distance on the plateau, where some of them

bivouacked at nightfall, covered by a few companies detached

for the purpose.

Losses

In the battle the English lost 106 officers, of whom

twenty-five were killed; nineteen sergeants killed, and 102

wounded; of rank and file, 318 killed, 1438 wounded; and

nineteen missing, supposed to be buried in the ruins of

Bourliouk; total 2002.

The French lost only three officers killed, yet their

official accounts placed their total loss at the disproportionate

number of 1340; but there were good reasons for believing that

this was a great exaggeration. Lord Raglan (says Kinglake)

believed that their whole loss in killed was sixty, and in

wounded 500, and there was a general belief in our army that

the French losses were slight.

The Russians stated their own losses at 5709.

As to the tactics of the Allies, they had before them a

position very difficult of access on their right, very

advantageous for defence in the centre, and with open and

undefended ground on their left.

Supposing they had neglected the part so difficult of

access near the sea, and carried their whole line inland, till their

right was across the post-road, and their left extending far

beyond the Russian right, in that case, if the- Russians had

held their position, with a powerful attack prepared against

their front, and a large force turning their right, a defeat would

have been to them absolute destruction. If, seeing the

maneuvre, Menschikoff had marched out of the position, and

formed across our left, backed on the Simpheropol road, he

would have gained a tactical advantage largely compensating

for his numerical inferiority, and great chances would have

been afforded to an able tactician thus operating on a flank

with his own retreat assured; in fact, there would have been a

large field open for skilful maneuvres on both sides, and the

Allies would at least have had the advantage of drawing him

from his position, when they might well have hoped that, with

ordinary equality of skill, they would have forced him back,

and gained the road to Sebastopol.

On the other hand, they had to consider whether they

would run any serious risk in thus leaving a space between

their right and the sea. Now a Russian force could only have

operated there by traversing the plateau swept by the guns of

the fleet, descending the difficult paths through the cliffs,

crossing the stream, and forming for attack with its back to the

sea, and with a retreat across the Alma and up the cliffs

impossible, except in case of the most absolute defeat of the

Allies.

This, therefore, need not be taken into the account, and

all considerations point to this suggested movement of the

Allied Army away from the sea as the right one.

The battle, as fought, showed a singular absence of

skill on all sides. The Russian general showed great

incompetency in leaving the issues of the cliffs unclosed, in

keeping his reserves out of action, in withdrawing his artillery

when it might have best served him, and .n leaving absolutely

unused his so greatly superior force of cavalry on ground very

well adapted to its action.

The part played by the French was not proportionate either

to their force, or to their military repute. Of the two divisions

brought at first on to the plateau, one brigade, that nearest the

sea, together with all the Turks, never saw the enemy, and had

no effect on the action ; and another division of the front line,

with easier ground, only arrived very late to the support of the

others. Though these others (three brigades) were opposed by

no overwhelming force, they hung back, and never, up to the

end of the battle, seriously engaged the Russians. No

favourable impression was left on the minds of the English by

their Allies' share in the action.

The English divisional generals were, as we have seen,

left to themselves, except for the order given to two of them to

attack; and it was inevitable, in their relative position to the

French, that they should advance straight to their front. This

they did, in the face of a formidable resistance, and with a

gallantry to which their losses testify. But when it had become

evident that no great operation against our flank was to be

attempted, and that the enemy was altogether committed to a

direct defence, our attack should have been so strong, so

concerted, and so fed and maintained, as to bring our whole

force to bear on the enemy.

Thus, if the Highland Brigade had crossed the river

along with the attacking divisions and beyond them, supported

by the Fourth Division and the cavalry, then the Light and

Second Divisions, secure on their flanks, and closely supported

by the Guards, could have brought their whole strength at once

to bear, while the Russian reserves would have found too much

to do in meeting the onset on their flank to reinforce the

defenders of the principal battery. But as there was no unity

and no concerted plan, our troops suffered accordingly.

The artillery, too, instead of being left to come into

action according to the views of its different commanders,

should have bad its part in supporting the attack distinctly

assigned to it. All, therefore, that we had to be proud of was the

dash and valour of the regiments engaged. These were very

conspicuous, and worthy of the traditions of the Peninsular

days. A French officer, who was viewing the field, where our

men lay, as they had fallen, in ranks, with one of our naval

captains, observed to him, "Well, you took the bull by the

horns -our men could not have done it."

Our cavalry, though so inferior in number, would

probably not have been deterred by that consideration from

engaging (as indeed it proved on a later occasion) but the part

assigned to it was that of observation and defence only. "I will

keep my cavalry in a bandbox," was said to have been Lord

Raglan's expression; and he was right, for it was all the army

had to depend on for the many essential duties which cavalry

must in such a case perform.

Chapter IV: The March Round Sebastopol to Balaclava

On the 19th the advance of the armies began. The French were

on the right, next the sea. The fact that we had cavalry and

they had none indicated the inland flank as ours.

On the 19th the advance of the armies began. The French were

on the right, next the sea. The fact that we had cavalry and

they had none indicated the inland flank as ours.

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com