Visit of the Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt to the Surrender Grounds in 1795

- Rochefoucauld-Liancourt Duke de la, French publicist,

b. in la Roche Gayon, 14 Jan., 1747 ; d. in Paris, March 28,

1827. As early as 1745 he carried on agricultural

improvements on his family estate, and in 1780, founded there,

at his own expense, a school of mechanical arts for soldiers'

sons, which has since became the school of "Arts et Metiers" of

France. He was a favorite of Louis XVI, and during the reign

of terror endeavored to save the King. Flying to England, he

remained there till 1794, when he came to the United States.

After traveling through the principal States, he bought a farm in

Pennsylvania, and spent some time in experiments.

At the restoration of Louis XVIII he was created a peer, and afterwards devoted himself to the prosecution of useful arts and to benevolent institutions. He established in Paris the first savings bank, and was also instrumental in introducing vaccination in France. He always advocated American principles and institutions, and acquired, through his benevolent and philanthropic actions, great popularity. His works include, among others, a "Voyage dans les Etats-Unis," 8 vols., New York, 1795-7-from which the above letter is taken.

In 1795, the then Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt visited the famous battle-fields of Saratoga, and in his published account of his travels in the new world upon his return gives a graphic account of the scenes of Burgoyne's surrender.

The Duc's Account

"I have seen," says the Duc, "John Schuyler, the eldest son of the general. For a few minutes I had already conversed with him at Schenectady, and was now with him at Saratoga. The journey to this place was extremely painful, on account of the scorching heat; but Saratoga is a township of too great importance to be passed by unobserved. If you love the English, are fond of conversing with them, and live with them on terms of familiarity and friendship, it is no bad thing if occasionally you can say to them, 'I have seen Saratoga.'

"Yes, I have seen this truly memorable place, which may be considered as the spot where the independence of America was sealed; for the events which induced Great Britain to acknowledge that independence were obviously consequences of the capture of General Burgoyne, and would, in all probability, never have happened without it. The dwelling-house of John Schuyler stands exactly on the spot where this important occurrence took place.*

- (*This is, of course, an error. He confounded it

with the fact that near the house the preliminary conferences

were exchanged. See Wilkenson and my Burgoyne's

Campaign.)

Fish creek, which flows close to the house, formed the line of defence of the camp of the English general, which was formed on an eminence a quarter of a mile from the dwelling. The English camp was also entirely surrounded with a mound of earth to strengthen its defence.

In the rear of the camp the German troops were posted by divisions on a commanding height, communicating with the eminence on which General Burgoyne was encamped. The right wing of the German corps had a communication with the left wing of the English, and the left extended towards the river. General Gates was encamped on the other side of the creek at the distance of an eighth of a mile from General Burgoyne, his right wing stretched toward the plain; but he endeavored to shelter his troops as much as possible from the enemy's fire until he resolved to form the attack.

General Neilson, at the head of the American militia, occupied the heights on the other side of the river, and engaged the attention of the left wing of the English while other American troops observed the movements of the right wing. In this position General Burgoyne surrendered his army. His provisions were nearly consumed, but he was amply supplied with artillery and ammunition.

The spot remains exactly as it then was, excepting the sole circumstance that the bushes, which were cut down in front of the two armies, are since grown up again. Not the least alteration has taken place since that time. The entrenchments still exist; nay, the footpath is still seen on which the adjutant of General Gates proceeded to the English general with the ultimatum of the American commander; the spot on which the council of war was held by the English officers remains unaltered. You see the way by which the English column, after it had been joined by the Germans, filed off by the left to lay down their arms within an ancient fort, which was constructed in the war under the reign of Queen Anne; you see the place where the unfortunate army was necessitated to ford the creek in order to reach the road to Albany, and to march along the front of the American army; you see the spot where General Burgoyne surrendered up his sword to General Gates.*

- (* For many years, until destroyed by fire, April 15,

1879, an old elm tree in the present village of Schuylerville,

near a blacksmith's shop, was supposed to mark the spot

where Burgoyne surrendered. This was a mistake; it was

under this tree that the articles of capitulation were signed,

and as such it is a memorable spot.)

You see where the man, who two months before had threatened all the rebels, their parents, their wives and their children with pillage, sacking, firing and scalping, if they did not join the English banner, was compelled to bend British pride under the yoke of these rebels, and when he underwent the two-fold humiliation as a ministerial agent of the English government to submit to the dictates of revolted subjects and a commanding general of disciplined regular troops, and to surrender up his army to a multitude of half-armed and half-clothed peasants. To sustain so severe a misfortune and not to die with despair exceeds not, it seems, therefore, the strength of man.

This memorable spot lies in a corner of the court-yard of John Schuyler.*

- (* The Lake Champlain canal now runs through the

site of the surrender.)

He was then a youth twelve years old, and placed on an

eminence, at the foot of which stood General Gates and near

which the American army was drawn up, to see their disarmed

enemies pass by. His estate includes all the tract of ground on

which both armies were encamped and he knows as it were

their every step. How happy must an American feel in the

possession of such property if his bosom be anywise

susceptible of warm feelings!

He was then a youth twelve years old, and placed on an

eminence, at the foot of which stood General Gates and near

which the American army was drawn up, to see their disarmed

enemies pass by. His estate includes all the tract of ground on

which both armies were encamped and he knows as it were

their every step. How happy must an American feel in the

possession of such property if his bosom be anywise

susceptible of warm feelings!

It is a matter of astonishment that neither Congress nor the Legislature of New York should have erected a monument on this spot reciting in plain terms this glorious event and thus calling it to the recollection of all men who should pass this way to keep alive the sentiments of intrepidity and courage and the sense of glory which for the benefit of America should be handed down among Americans from generation to generation." *

-

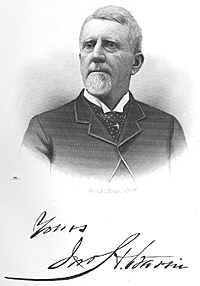

(*The Saratoga Monument, at Schuylerville, N. Y.,

has since been erected-mainly through the patriotic efforts in

Congress of Hon. John H. Starin (at right) -- now, 1895, president of the

SARATOGA MONUMENT Association. The corner-stone of

the monument laid in 1877 was donated by Booth Bros., New

York, who were also the builders of the monument.)

Back to Battlegrounds of Saratoga Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com