The disastrous result of the campaign of General Burgoyne is to be ascribed more to his own blunders and incompetency than to any special military skill on the part of his conqueror. In December, 1776, Burgoyne concerted with the British ministry a plan for the campaign of 1777. A large force was to proceed toward Albany from Canada, by way of the lakes, while another large body advanced up the Hudson, in order to cut off communication between the northern and southern colonies, in the expectation that each section, being left to itself, would be subdued with little difficulty.

At the same time Col. St. Leger was to make a diversion on the Mohawk river. In pursuance of this plan, in the early summer of 1777 he sailed down Lake Champlain, forced the evacuation of Crown Point and Ticonderoga, defeated the Americans badly at Hubbardton,. and took possession of Skenesborough (Whitehall).*

- *The royal army was divided into three brigades,

under Major-General Phillips, of the Royal Artillery, and

Brigadier-Generals Fraser and Hamilton. The German troops,

consisting of one regiment of Hessian. Rifles, a corps of

dismounted dragoons, and a mixed force of Brunswickers, of

which 100 were artillerists, were distributed among the three

brigades, with one corps of reserve under Colonel Breyman,

and were commanded by Major-General Riedesel.

Up to this time all had gone well. From that point, however, his fortunes began to wane. His true course would have been to return to Ticonderoga, and thence up Lake George to the fort of that name, whence there was a direct road to Fort Edward; instead of which he determined to push on to Fort Ann and Fort Edward, over roads that were blocked up by the enemy -- a course which gave Schuyler ample time to gather the yeomanry together and effectually oppose his progress.

Nor was this all. On his arrival at Fort Ann, instead of advancing at once on Fort Edward, and thence to Albany before Schuyler had time to concentrate his forces in his front, he sent a detachment of Brunswickers, under Colonel Baum, to Bennington, to surprise and capture some stores which he had heard were at that place. General Riedesel, who commanded the German allies, was totally opposed to this diversion. but being overruled, he proposed that Baum should march in the rear of the enemy, by way of Castleton, toward the Connecticut river. Had this plan been adopted, the probability is that the Americans would not have had time to prevent Baum from falling unawares upon their rear.

Burgoyne, however, against the advice of Riedesel and Phillips, insisted obstinately on his plan, which was that Baum should cross the Battenkil opposite Saratoga, move down the Connecticut. river in a direct line to Bennington, destroy the magazine at that Place, and mount the Brunswick dragoons, who were destined to form part of the expedition. In this latter order a fatal blunder was committed, by employing troops the most awkward and heavy in an enterprise where every thing depended on the greatest celerity of movement, while the rangers, who were lightly equipped, were left behind.

Dragoon Uniform and Equipment

Dragoon Uniform and Equipment

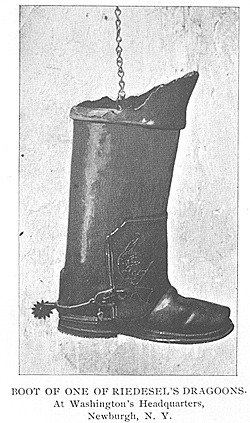

Let us look for a moment at a fully equipped Brunswick dragoon as he appeared at this time. He wore high and heavy Jack-boots, with large, long spurs, stout and stiff leather breeches, gauntlets reaching high up upon his arms, and a hat with a huge tuft of ornamental feathers.*

- * The weight of the Brunswick Jack-Boot -- a

representation of which is here given - is 5 1/2 lbs. or 11

lbs. for the pair -- when, moreover, it is observed that

a considerable portion of the top has rotted away, the

boot, when new, must have weighed fully 6 lbs. or 12

lbs. for the pair!! And this only for the boots, to

say nothing of the dragoon's other equipments. The

man, who wore this boot, was captured at Saratoga.

He travelled on foot with other prisoners on his way to

Easton, Pa., as far as Middlehope (North Newburgh),

where he exchanged his boots for a lighter pair.

On his side he trailed a tremendous broadsword, a short but clumsy carbine was slung over his shoulder, and down his back, like a Chinese mandarin's dangled a long queue. Such were the troops sent out by the British general on a service requiring the lightest of light skirmishers. The latter, however, did not err from ignorance.

From the beginning of the campaign the English officers had ridiculed these unwieldy troopers, who strolled about the camp with their heavy sabres dragging on the ground, saying (which was a fact) that the hat and sword of one of them were as heavy as the whole of an English private's equipment. But, as if this was not sufficient, these light dragoons were still further cumbered by being obliged to carry flour and drive a herd of cattle before them for their maintenance on the way.

The result may be easily foreseen. By a rapid movement of the Americans under Stark, Baum was cut off from his English allies, who fled and left him to fight alone, with his awkwardly equipped squad, an enemy far superior in numbers. After maintaining his ground for more than two hours, his ammunition gave out, and being wounded in the abdomen by a bullet, he was forced to surrender, having lost in killed 360 men out of 400.

Yet, even with all these disadvantages, it is doubtful upon whose banners victory would have perched, had not Burgoyne, though having ample time, failed to support Baum by keeping Breyman's division too far behind.

With the failure of this expedition against Bennington, the first lightning flashed from Burgoyne's hitherto serene sky. The soldiers as well as their officers had set out on this campaign with cheerful hearts, for, the campaign successfully brought to a close, all must end in the triumph of the royal arms.

"Britons never go back," Burgoyne exultantly had said, as the flotilla passed down Lake Champlain. Now, however, the Indians deserted by scores, and an almost general consternation and languor took the place of the former confidence and buoyancy.*

- * For a most romantic incident, said to have been the

cause of this desertion of Burgoyne's Indian allies, see "The

Lost Child" in Tales of the Garden of Kosciusko by

Samuel L. Knapp, New York, 1834.

Crossing the Hudson

On the 13th of September the royal army crossed the Hudson by a bridge of boats, with the design of forming a junction with Sir Henry Clinton at Albany. It encamped on the heights and plains of Saratoga, near the mouth of Fish Creek (the present site of Schuylerville), within a few miles of the northern division of the Continentals under Gates; Burgoyne selecting General Schuyler's house as his headquarters.

After the evacuation of Fort Edward, Schuyler had fallen down the river, first to Stillwater, and then to Van Schaick's Island, at the mouth of the Mohawk. *

- * The entrenchments which Schuyler threw up on this

island, in anticipation of Burgoyne's advance, are yet (1895)

plainly to be seen, even by the traveller on the Troy &

Saratoga R. R.

On the 19th of August, however, he was superseded by Gates, who, on the 8th of September, advanced with 6000 men to Bemus Heights, three miles north of Stillwater. These heights were at once fortified, under the direction of Kosciusko, by a line of intrenchments running from west to east, half a mile in length, and terminating on the east end on the west side of the intervale.

The right wing occupied a hill nearest the river, and was protected in front by a wide marshy ravine, and behind by an abatis. The left wing, commanded by Arnold (who, after the defeat of St. Leger at Fort Stanwix, had joined Gates), extended on to a height three-quarters of a mile further north, its left flank being also protected on the hillside by fallen trees. Gates's head-quarters were in the centre, a little south of what was then and is now known as the "Neilson Farm."

On the 15th, Burgoyne gave the order to advance in search of the enemy, supposed to be somewhere in the forest; for, strange as it appears, that general had no knowledge of the position of the Americans, nor had he taken any pains to inform himself upon this vital point. The army, in gala dress, with its left wing resting on the Hudson, set off on its march, with drums beating, colors flying, and their arms glistening in the sunshine of that lovely autumn day.

"It was a superb spectacle," says an eye-witness, "reminding one of a grand parade in the midst of peace."

That night they pitched their camp at "Dovogat's House" (Coveville). On the following morning the enemy's drums were heard calling the men to arms; but, although in such close proximity, the invading army knew not whence the sounds came, nor in what strength he was posted. Indeed, it does not seem that up to this time Burgoyne had sent off patrols or scouting parties to discover the situation of the enemy. Now, however, he mounted his horse to attend to it himself, taking with him a strong body-guard, consisting of the four regiments of Specht and Hesse-Hanau, with six heavy pieces of ordnance, and 200 workmen to construct bridges and roads. This was the party with which he proposed "to scout, and, if occasion served" -- these were his words -- " to attack the rebels on the spot."

This remarkable scouting party moved with such celerity as to accomplish two and a half miles the first day, when, in the evening, the entire army, which had followed on, encamped at "Sword's House," within five miles of the American lines.

The night of the 18th passed quietly, the patrols that had finally been sent out having returned without discovering any trace of the enemy. Indeed, it is a noteworthy fact that throughout the entire campaign Burgoyne was never able to obtain accurate knowledge either of the position of the Americans, or of their movements, whereas all his own plans were publicly known long before they were officially given out in orders.

"I observe," writes Baroness Riedesel, at this time, "that the wives of the officers are beforehand informed of all the military plans. Thus the Americans anticipate all our movements, and expect us wherever we arrive ; and this, of course, injures our affairs."

On the morning of the 19th a further advance was ordered -- an advance which prudence dictated should be made with the greatest caution. The army was now in the immediate vicinity of an alert and thoroughly aroused enemy, of whose strength it knew as little as of the country. Notwithstanding this, the army not only was divided into three columns, marching half a mile apart, but at eleven o'clock a cannon, fired as a signal for the start, informed the Americans of the position and forward movement of the British.

The left column, which followed the river road, consisted of four German regiments and the Fortyseventh British, the latter covering the bateaux. These troops, together with all the heavy artillery and baggage, were under the command of General Riedesel.

The right column, made up of the English grenadiers and light infantry, the Twenty-fourth Brunswick Grenadiers, and the light battalion, with eight 6-pounders, under Lieutenant- Colonel Breyman, were led by General Fraser, and followed the present road from Quaker -Springs to Stillwater on the Heights.

The centre column, also on the Heights, and midway between the left and right wings, consisted of the Ninth, Twentieth, Twenty-first, and Sixty-second regiments, with six 6-pounders, and was led by Burgoyne in person. The front and flanks of the center and right columns were protected by Canadians, Provincials, and Indians. The march was exceedingly tedious, as frequently new bridges had to be built and trees cut down and removed.

The Action Starts

About one o'clock in the afternoon, Colonel Morgan, who, with his sharp-shooters, had been detached to watch the movements of the British and harass them, owing to the dense woods, unexpectedly fell in in with the centre column and sharply attacked it. Whereupon Fraser, on the right, wheeled his troops, and coming up, forced Morgan to give way. A regiment being ordered to the assistance of the latter, whose riflemen had been sadly scattered by the vigor of the attack, the battle was renewed with spirit.

By four o'clock the action had become general, Arnold, with nine Continental regiments and Morgran's corps, having completely engaged the whole force of Burgoyne and Fraser. The contest, accidentally begun in the first instance, now assumed the most obstinate and determined character, the soldiers being often engaged hand to hand. The ground, being mostly covered with woods, embarrassed the British in the use of their field artillery. while it gave a corresponding advantage to Morgan's sharp-shooters.

The artillery fell into the hands of the Americans at every alternate discharge, but the latter could neither turn it upon the enemy nor bring it off. The woods prevented the last, and the want of a match the first, as the linstock was invariably carried away, and the rapidity of the transitions did not allow the Americans time to provide one.

Meanwhile General Riedesel, who had kept abreast of the other two columns, hearing the firing, on his own responsibility, and guided only by the sound of the cannon, hastened, at five o'clock, with two regiments through the woods to the relief of his commander-in-chief. When he arrived on the scene, the Americans were posted on a corner of the woods, having on their right flank a deep, muddy ravine, the bank of which had been rendered inaccessible by stones and underbrush. In front of this corner of the forest, and entirely surrounded by dense woods, was a vacant space, on which the English were drawn up in line.

The struggle was for the possession of this clearing, known then, as it is to this day, as "Freeman's Farm." It had already been in possession of both parties, and now served as a support for the left flank of the English right wing, the right flank being covered by the corps of Fraser and Breyman. The Continentals had for the sixth time hurled fresh troops against the three British regiments, the Twentieth, Twenty-first and Sixty-second.

The guns on this wing were already silenced, there being no more ammunition, and the artillery-men having been either killed or wounded. These three regiments had lost half their men, and now formed a small band surrounded by heaps of the dead and dying. The timely arrival of the German general alone saved the army of Burgoyne from total rout. Charging on the double-quick with fixed bayonets, he repelled the American; and Fraser and Breyman were preparing to follow up the advantage, when they were recalled by Burgoyne and reluctantly forced to retreat. General Schuyler, referring to this in his diary, says : "Had it not been for this order of the British general, the Americans would have been, if not defeated, at least held in such check as to have made-it a drawn battle, and an opportunity afforded the British to collect much provision, of which he [sic] stood sorely in need."

The British officers also shared the same opinion. Fraser and Riedesel severely criticised the order, telling its author in plain terms that " he did not know how to avail himself of his advantages." Nor was this feeling confined to the officers. The privates gave vent to their dissatisfaction against their general in loud express ions of scorn as he rode down the line. This reaction was the more striking because they had placed the utmost confidence in his capacity at the beginning of the expedition. They were, also, still more confirmed in their dislike by the general belief that he was addicted to drinking.

Night put an end to the conflict. The Americans withdrew within their lines, and the British and German forces bivouacked on the battle-field, the Brunswickers composing in part the right wing. Both parties claimed the victory; yet as the intention of the Americans was not to advance, but to maintain their position, and that of the English not to maintain theirs, but to gain ground, it is easy to see which had the advantage of the day, The loss of the former was between 300 and 400, including Colonels Adams and Coburn, and of the latter from 60 to 1000, Captain Jones, of the artillery, an officer of great merit, being among the killed.

General Burgoyne resolved after the engagement to advance no further for the present, but to await the arrival at Albany of Sir Henry Clinton, who had promised to attempt the ascent of the Hudson for his relief. Accordingly, on the following day (the 20th), he made the site of the late battle his extreme right, and extended his entrenchments across the high ground to the river. For the defense of the right wing, a redoubt (known as the "Great Redoubt") was thrown up in the late battle-field, near the corner of the woods that had been occupied by the Americans during the action, on the eastern edge of the ravine.

The defense of this position was intrusted to the corps of Fraser. The reserve corps of Breyman was posted on an eminence on the western side of the ravine, for the protection of the right flank of Fraser's division. The right wing of the English brigade (Hamilton's) was placed in close proximity to the left wing of Fraser, thus extending the line on the left to the river-bank (Wilbur's Basin), where were placed the hospitals and supply trains. The entire front was protected by a deep muddy ditch running goo paces in front of the outposts of the left wing. This ditch ran in a curve around the right wing of the English brigade, thereby, separating Fraser's corps from the main body. General Burgoyne made his headquarters between the English and German troops, on the heights at the left wing. This was the new camp at Freeman's Farm.

During the period of inaction which now intervened, a part of the army, says the private journal of one of the German officers, was so near its antagonist that "we could hear his morning and evening guns, his drums, and other noises in his camp very distinctly; but we knew not, in the least, where he stood, nor how he was posted, much less how strong he was."

"Undoubtedly," naively adds the journal," a rare case in such a situation."

Meanwhile the work of fortifying the camp was continued. A place d'armes was laid out in front of the regiments, and fortified with heavy batteries. During the night of the 21st, considerable shouting was heard in the American camp. This, accompanied by the firing of cannon, led the British to believe that some holiday was being celebrated. Again, in the night of the 23d, more noise was heard in the same direction.

"This time, however," says the journal of another Officer, "it may have proceeded from working parties, as the most common noise was the rattling of chains."

On the 28th, a captured cornet, who had been allowed by Gates to return to the British camp for five days, gave an explanation of the shouting heard on the night of the 21st. This was that General Lincoln had attempted to surprise Ticonderoga, and, though unsuccessful, had captured four companies of the Fifty-third, together with a ship and one bateau. Thus Burgoyne was indebted to an enemy in his front for information respecting his own posts in his rear.

But the action of the 19th had essentially diminished his strength, and his situation began to grow critical. His dispatches were intercepted, and his communications with Canada cut off by the seizure of the posts at the head of Lake George. The pickets were more and more molested; the army was weakened by the sick and wounded, and the enemy swarmed on its rear and flanks, threatening the strongest positions.

In fact, the army was as good as cut off from its outposts, while, in consequence of its close proximity to the American camp, the soldiers had but little rest. The nights, also, where rendered hideous by the howls of large packs of wolves that were attracted by the partially buried bodies of those slain in the action of the 19th.

On the 1st of October a few English soldiers who were digging potatoes in a field a short distance in the rear of headquarters, and within the camp, were surprised by the enemy, who suddenly issued from the woods and carried off the men in the very faces of their comrades.

There were now only sufficient rations for sixteen days, and foraging parties, necessarily composed of a large number of men, were sent out daily. At length Burgoyne was obliged to cut down the ordinary rations to a pound of bread and a pound of meat; and as he had heard nothing from Clinton, he became seriously alarmed.

Accordingly, on the evening of the 5th of October, he called a council of war. Riedesel and Fraser advised an immediate falling back to their old position behind the Battenkil, Phillips declined giving an opinion, and Burgoyne reserved his decision until he had made a reconnaissance in force it to gather forage and ascertain definitely the position of the enemy, and whether it would be advisable to attack him." Should the latter be the case, he would, on the day following the reconnaissance, advance on the Americans with his entire army ; but if not, he would march back to the Battenkil.

Battle Begins

At ten o'clock on the morning of October 7, liquor and rations having been previously issued to the army, Burgoyne, with 1500 men, eight cannon, and two howitzers, started on his reconnaissance accompanied by Generals Riedesel, Phillips, and Fraser.

The Canadians and Indians were sent ahead to make a diversion in the rear of the Continentals, but they were speedily discovered, and after a brisk skirmish of half an hour, driven back. The British advanced in three columns toward the left wing of the American position, entered a wheat field about 200 rods southwest of the site of the action of the 19th, deployed into line, and began cutting up wheat for forage. The grenadiers, under Major Ackland, and the artillery, under Major Williams, were stationed upon a gentle eminence. The light infantry, skirted by a low ridge of land, and under the Earl of Balcarras, was placed on the extreme right. The centre was composed of British and German troops under Phillips and Riedesel. In advance of the right wing General Fraser had command of a detachment Of 500 picked men. The movement having been seasonably discovered, the centre advanced guard of the Americans beat to arms. Colonel Wilkinson, Gate's adjutant-general, being at head-quarters at the moment, was dispatched to ascertain the cause of the alarm. He proceeded to within sixty rods of the enemy, and, returning, informed General Gates that they were foraging, attempting also to reconnoitre the American left, and likewise, in his opinion, offering battle.

"What is the nature of the ground, and what your opinion?" asked Gates.

"Their front is open," Wilkinson replied, "and their flanks rest on woods, under cover of which they may be attacked; their right is skirted by a height. I would indulge them."

"Well, then," rejoined Gates, order on Morgan to begin the game." At his own suggestion, however, Morgan was allowed to gain the ridge on the enemy's right by a circuitous course, while Poor's and Learned's brigades should attack his left.

The movement was admirably executed. At half past two o'clock in the afternoon, the New York and New Hampshire troops marched steadily up the slope of the knoll on which the British grenadiers and the artillery under Ackland and Williams were stationed. Poor had given them orders not to fire until after the first discharge of the enemy, and for a moment there was an awful stillness, each party seeming to bid defiance to the other.

At length the artillerymen and grenadiers began the action by a shower of grape and musket-balls, which had no other effect than to break the branches of the trees over the heads of the Americans, who, having thus received the signal, rushed forward, firing, and opening to the right and left. Then again forming on the flanks of the grenadiers, they mowed them down at every shot, until the top of the hill was gained.

Here a bloody and hand-to-hand struggle ensued, which lasted about thirty minutes, when, Ackland, being badly hurt, the grenadiers gave way, leaving the ground thickly strewn with their dead and wounded. In this dreadful conflict one field-piece that had been taken and re-taken five times, finally fell into the hands of the Americans.

Soon after Poor began the attack on the grenadiers, a flanking party of British was discerned advancing through the woods upon which Colonel Cilley was ordered to intercept them. As he approached near to a brush fence the enemy rose from behind and fired, but so hurriedly that only a few balls took effect.

The officer in command then ordered his men to "fix bayonets, and charge the damned rebels."

Colonel Cilley, who heard this order, replied, "It takes two to play that game. Charge, and we'll try it!"

His regiment charged at the word, and firing a volley in the faces of the British, caused them to flee, leaving many of their number dead upon the field.

As soon as the action began on the British left, Morgan, true to his purpose, poured down like a torrent from the ridge that skirted the flanking party of Fraser, and attacked them so vigorously as to force them back to their lines; then, by a rapid movement to the left, he fell upon the flank of the British right with such impetuosity that it wavered and seemed on the point of giving way.

At this critical moment, Major Dearborn arrived on the field with two regiments of New England troops, and delivered so galling a fire upon the British that they broke and fled in wild confusion. They were, however, quickly rallied by Balcarras behind a fence in rear of their first position, and led again into action.

The Continentals next threw their entire force upon the centre, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Specht with 300 men. Specht, whose left flank had been exposed by the retreating of the grenadiers, ordered the two regiments of Rhetz and Hesse-Hanan to form a curve, and, supported by the artillery, thus covered his flank, which was in imminent danger. He maintained himself long and bravely in this precarious situation, and would have stood his ground still longer had he not been separated from Balcarras in consequence of the latter, through a misunderstanding of Burgoyne's orders, taking up another position with his light infantry.

Thus Specht's right flank was as much exposed as his left. The brunt of the action now fell on the Germans, who alone had to sustain the impetuous onset of the Americans.

Brigadier-General Fraser, who, up to this time, had been stationed on the right, noticed the critical situation of the centre, and hurried to its succor with the Twenty-fourth Regiment. Conspicuously mounted on an iron-gray horse, he was all activity and vigilance, riding from one part of the division to another, and animating the troops by his example. Perceiving that the fate of the day rested upon that officer, Morgan, who with his riflemen, was immediately opposed to Fraser's corps, took a few of his sharpshooters aside, among whom was the celebrated marksman "Tim" Murphy -- men on whose precision of aim he could rely -- and said to them, "That gallant officer yonder is General Fraser. I admire and respect him, but it is necessary for our good that he should die. Take your station in that cluster of bushes and do your duty."

Within a few moments a rifle-ball cut the crupper of Fraser's horse, and another passed through his horse's mane. Calling his attention to this, Fraser's aid said, "It is evident that you are marked out for particular aim; would it not be prudent for you to retire from this place?"

Fraser replied, "My duty forbids me to fly from danger."

The next moment he fell mortally wounded by a ball from the rifle of Murphy, and was carried off the field by two grenadiers.

Upon the fall of Fraser, dismay seized the British, while a corresponding elation took possession of the Americans, who, being reinforced at this juncture by General Tenbroeck with 3000 New York Militia, pressed forward with still greater vehemence. Up to this time Burgoyne had been in the thickest of the fight, and now, finding himself in danger of being surrounded, he abandoned his artillery, and ordered a retreat to the "Great Redoubt."

British Retreat

This retreat took place exactly fifty-two minutes after the first shot was fired, the enemy leaving all the cannon on the field, except the two howitzers, with a loss of more than 400 men, and among them the flower of his officers, viz., Fraser, Ackland, Williams, Sir Francis Clarke, and many others.

The retreating British troops had scarcely entered their lines, when Arnold, notwithstanding he had been refused a command by Gates, placed himself at the head of the Continentals, and, under a terrific fire of grape and musket- balls, assaulted their works from right to left. Mounted on a dark brown horse, he moved incessantly at a full gallop over the field, giving orders in every direction; sometimes in direct opposition to those of the commander, at others leading a platoon in person, and exposing himself to the hottest fire of the enemy.

"He behaved;" says Samuel Woodruff, a sergeant in the battle, in a letter to the late Colonel Stone, "more like a madman than a cool and discreet officer;"

But if it were "madness," judging from its effect there was "method in it." With a part of Patterson's and Glover's brigades, he attacked, with the ferocity of a tiger, the "Great Redoubt," and encountering the light infantry of Balcarras, drove it at the point of the bayonet from a strong abatis into the redoubt itself. Then spurring boldly on, exposed to the cross-fire of the two armies, he darted to the extreme right of the British camp.

This right-flank defense of the enemy was occupied by the Brunswick troops under Breyman, and consisted of a breastwork of rails piled horizontally between perpendicular pickets, and extended 200 yards across an open field to some high ground on the right, where it was covered by a battery of two guns. The interval from the left of this defense to the "Great Redoubt" was intrusted to the care of the Canadian Provincials.

In front of the rail breastwork the ground declined in a gentle slope of 120 yards, when it sunk abruptly. The Americans had formed a line under this declivity, and, covered breast-high, were warmly engaged with the Germans, when, about sunset, Learned came up with his brigade in open column, with Colonel Jackson's regiment, then in command of Lieutenant- Governor Brooks, in front. On his approach he inquired where he could "put in with most advantage." A slack fire was just then observed in that part of the enemy's line between the Germans and light infantry, where were stationed the Canadian Provincials, and Learned was accordingly requested to incline to the right, and attack that point.

This slack fire was owing to the fact that the larger part of the Canadian companies belonging to the skirmishing expedition of the morning were absent from their places, part of them being in the "Great Redoubt," and the others not having returned to their position. Had they been in their places, it would have been impossible, Riedesel thinks, for the left flank of Breyman to have been surrounded.

Be this as it may, on the approach of Learned the Canadians fled, leaving the German flank uncovered, and at the same moment Arnold, arriving from his attack on the "Great Redoubt," took the lead of Learned's brigade, and passing through the opening left by the Canadians, attacked the Brunswickers on their left flank and rear with such success that the chivalric Breyman was killed, and they themselves force to retreat, leaving the key of the British position in the hands of the Americans. Lieutenant-Colonel Specht, in the "Great Redoubt," hearing of this disaster, hastily rallied four officers and fifty men, and started in the growing dusk to retake the entrenchment.

Unacquainted with the road, he met a pretended royalist in the woods, who promised to lead him to Breyman's corps; but his guide treacherously delivered him into the hands of the Americans, by whom he and the four officers were captured.

The advantage thus gained was retained by the Americans, and darkness put an end to an action equally brilliant and important to the Continental arms. Great numbers of the enemy were killed, and 200 prisoners taken. Burgoyne himself narrowly escaped, one ball having passed through his hat, and another having torn his waistcoat. The American loss was inconsiderable.

In their final retreat the Brunswickers turned and delivered a parting volley, which killed Arnold's horse and wounded the general in the same leg that had been injured by a musket ball at the storming of Quebec two years previously. It was at this moment, while he was striving to extricate himself from his saddle, that Major Armstrong rode up and delivered to him an order from Gates, to return to camp, fearing he "might do some rash thing."

"He indeed," says Mr. Lossing, "did a rash thing in the eyes of military discipline; he led troops to victory without an order from his commander."

"It is a curious fact," says Sparks, "that an officer who really had not command in the army was the leader of one of the most spirited and important battles of the Revolution. His madness, or rashness, or whatever it may called, resulted most fortunately for himself. The wound he received at the moment of rushing into the very arms of danger and death added fresh lustre to his military glory, and was a new claim to public favor and applause."

In the heat of the action he struck an officer on the head with his sword and wounded him - an indignity which might justly have been retaliated on the spot, and in the most fatal manner. The officer did, indeed, raise his gun to shoot him, but he forbore, and the next day, when he demanded redress, Arnold declared his entire ignorance of the act, and expressed his regret. Wilkinson ascribed his rashness to intoxication, but Major Armstrong, who, with Samuel Woodruff, assisted in removing him from the field, was satisfied that this was not the case. Others ascribed it to opium.

This, however, is conjecture, unsustained by proofs of any kind, and consequently improbable. His vagaries may, perhaps, be sufficiently explained by the extraordinary circumstances of wounded pride, anger, and desperation in which he was placed. But his actions were certainly rash when compared with "the stately method of the commander-in-chief, who directed by orders from his camp what his presence should have sanctioned in the field."

Indeed, the conduct of Gates does not compare favorably either with that of his own generals or of his opponent. While Arnold and Burgoyne were in the hottest of the fight, boldly facing danger, and almost meeting face to face, Gates, according to the statement of his adjutant-general, was discussing the merits of the Revolution with Sir Francis Clarke, Burgoyne's aide-de-camp -- who, wounded and a prisoner, was lying upon the commander's bed -- seemingly more intent upon winning the verbal than the actual battle. A few days afterward Sir Francis died.

Gates has been suspected of a lack of personal courage. fie certainly looked forward to a possible retreat, and while he can not be censured for guarding against every emergency, he was not animated by the spirit which led Cortez to burn his ships behind him.

At the beginning of the battle, QuartermasterGeneral Lewis was directed to take eight men with him to the field, to convey to Gates information from time to time concerning the progress of the action.

At the same time the baggage trains were loaded up, ready to move at a moment's warning. The first information that arrived represented the British troops to exceed the Americans, and the trains were ordered to move on; but by the time they were under motion, more favorable news was received, and the order was countermanded.

Thus they continued alternately to move on and halt, until the joyful news, "The British have retreated!" rang through the camp, and reaching the attentive ears of the teamsters, they all, with one accord, swung their hats and gave three long and loud cheers. The glad tidings spread so swiftly that, by the time the victorious troops had returned to their quarters, the American camp was thronged with inhabitants from the surrounding country, and presented a scene of the greatest exultation.

From the foregoing account it will be seen that the term, Battle of Bemus Heights," used to designate the action of October 7, is erroneous and calculated to mislead. The maps show that the second engagement began on ground 200 rods southwest of the site of the first (known as the "Battle of Freeman's Farm"), and ended on the same ground on which that action was fought. The only interest, in fact, that attaches to Bemus Heights -- fully one mile and a quarter south of the battleground -- is that they were the headquarters of Gates during and a short time previous to the battle. This action is called variously the "Battle of Bemus Heights" and "Saratoga." Properly, the two engagements should be designated as the "First and Second Battles of Saratoga."

On the morning of the 8th, before daybreak, Burgoyne left his position, now utterly untenable, and defiled to the meadows by the river, where were his supply trains; but was obliged to delay his retreat until the evening, because his hospital could not be sooner removed. He wished also to avail himself of the darkness. The Americans immediately moved forward and took possession of the abandoned camp. Burgoyne having, concentrated his forces upon some heights, which were strong by nature, and covered by a ravine running parallel with the intrenchments of his late camp, a random fire of artillery and smallarms was kept up through the day, particularly on the part of the German chasseurs and the Provincials.

These, stationed in coverts of the ravine, kept up an annoying fire upon every one crossing their line of vision, and it was by a shot from one of these lurking parties that General Lincoln received a severe wound in the leg while riding near the line. It was evident, from the movements of the British, that they were preparing to retreat; but the American troops, having, in the delirium of joy consequent upon their victory, neglected to draw and eat their rationsbeing withal not a little fatigued with the two days' exertions, fell back to their camp, which had been left standing in the morning. Retreat was, indeed, the only alternative left to the British commander, since it was now quite certain that he could not cut his way through the American army, and his supplies were reduced to a short allowance for five days.

Last Moments of Fraser

Meanwhile, in addition to the chagrin of defeat, a deep gloom pervaded the British camp. The gallant and beloved Fraser -- the life and soul of the army lay dying in the little house on the river bank occupied by Baroness Riedesel. That lady has described this scene with such unaffected pathos that we give it in her own words, simply premising that on the previous day she had expected Burgoyne, Phillips and Fraser to dine with her after their return from the reconnaissance. She says:

"About four o'clock in the afternoon, instead of the guests who were to have dined with us, they brought in to me upon a litter poor General Fraser, mortally wounded. Our dining-table, which was already spread, was taken away, and in its place they fixed up a bed for the general. I sat in a corner of the room, trembling and quaking. The noises grew continually louder. The thought that they might bring in my husband in the same manner was to me dreadful, and tormented me incessantly. The general said to the surgeon, "Do not conceal any thing from me. Must I die?"

The ball had gone through his bowels, precisely as in the case of Major Harnage. Unfortunately, however, the general had eaten a hearty breakfast, by reason of which the intestines were distended, and the ball had gone through them. I heard him often, amidst his groans, exclaim, 'O fatal ambition! Poor General Burgoyne! My poor wife!' Prayers were read to him. He then sent a message to General Burgoyne, begging that he would have him buried the following day at six o'clock in the evening, on the top of a hill which was a sort of a redoubt. I knew no longer which way to turn. The whole entry was filled with the sick, who were suffering with camp sickness -a kind of dysentery. I spent the night in this manner: at one time comforting Lady Ackland, whose husband was wounded and a prisoner, and at another looking after my children, whom I had put to bed.

As for myself, I could not go to sleep, as I had General Fraser and all the other gentlemen in my room, and was constantly afraid that my children would wake up and cry, and thus disturb the poor dying man, who often sent to beg my pardon for making me so much trouble. About three o'clock in the morning they told me that he could not last much longer. I had desired to be apprised of the approach of this moment. I accordingly wrapped up the children in the coverings, and went with them into the entry. Early in morning, at eight o'clock, he died.

"After they had washed the corpse, they wrapped it in a sheet and laid it on a bedstead. We then again came into the room, and had this sad sight before us the whole day. At every instant, also, wounded officers of my acquaintance arrived, and the cannonade again began. A retreat was spoken of, but there was not the least movement made toward it. About four o'clock in the afternoon I saw the new house which had been built for me, in flames; the enemy, therefore, were not far from us. We learned that General Burgoyne intended to fulfil the last wish of General Fraser, and to have him buried at six o'clock in the place designated by him. This occasioned an unnecessary delay, to which a part of the misfortune of the army was owing.

"Precisely at six o'clock the corpse was brought out, and we saw the entire body of generals with their retinues assisting at the obsequies. The English chaplain, Mr. Brudenell, performed the funeral services. The cannon-balls flew continually around and over the party. The American general, Gates, afterward said that if he had known that it was a burial, he would not have allowed any firing in that direction.

Many cannon-balls also flew not far from me, but I had my eyes fixed upon the hill, where I distinctly saw my husband in the midst of the enemy's fire, and therefore I could not think of my own danger."

"Certainly," says General Riedesel, in his journal, "it was a real military funeral -- one that was unique of its kind."

General Burgoyne has himself described this funeral with his usual eloquence and felicity of expression:

"The incessant cannonade during the solemnity; the steady attitude and unaltered voice with which the chaplain officiated, though frequently covered with dust, which the shot threw up on all sides of him; the mute but expressive mixture of sensibility and indignation upon every countenance -- these objects will remain to the last of life upon the mind of every man who was present.

The growing duskiness added to the scenery, and the whole marked a character of that juncture that would make one of the finest subjects for the pencil of a master that the field ever exhibited. To the canvass, and to the faithful page of a more important historian, gallant friend! I consign thy memory. There may thy talents, thy manly virtues, their progress and their period, find due distinction; and long may they survive, long after the frail record of my pen shall be forgotten!"

As soon as the funeral services were finished and the grave closed, an order was issued that the army should retreat as soon as darkness had set in; and the commander who, in the beginning of the campaign, had vauntingly uttered in general orders that memorable sentiment, "Britons never go back," was now compelled to steal away in the night, leaving his hospital, containing upward of 400 sick and wounded, to the mercy of a victorious and hitherto despised enemy. Gates in this, as in all other instances, extended to his adversary the greatest humanity.

British Withdraw

The army began its retrograde movement at nine o'clock on the evening of the 8th, in the midst of a pouring rain, Riedesel leading the van, and Phillips bringing up the rear with the advanced corps.

In this retreat the same lack of judgment on the part of Burgoyne is apparent. Had that general, as Riedesel and Phillips advised, fallen immediately back across the Hudson, and taken up his former position behind the Battenkil, not only would his communications with Lake George and Canada have been restored, but he could at his leisure have awaited the movements of Clinton. Burgoyne, how- ever, having arrived at Dovogat two hours before daybreak on the morning of the 9th, gave the order to halt, greatly to the surprise of his whole army.

"Every one," says the journal of Reidesel, itwas, notwithstanding, even then of the opinion that the army would make but a short stand, merely for its better concentration, as all saw that haste was of the utmost necessity, if they would get out of a dangerous trap."

At this time the heights of Saratoga, commanding the ford across Fish Creek, were not yet occupied by the Americans in force, and up to seven o'clock in the morning the retreating army might easily have reached that place and thrown a bridge across the Hudson. General Fellows, who, by the orders of Gates occupied the heights at Saratoga opposite the ford, was in an extremely critical situation.

On the night of the 8th, Lieutenant-Colonel Sutherland, who had been sent forward to reconnoitre, crossed Fish Creek, and, guided by General Fellows's fires, found his camp so entirely unguarded that he marched round it without being hailed. He then returned, and, reporting to Burgoyne, entreated permission to attack Fellows with his regiment, but was refused.

"Had not Burgoyne halted at Dovogat," says Wilkinson, "he must have reached Saratoga before day, in which case Fellows would have been cut up, and captured or dispersed, and Burgoyne's retreat to Fort George would have been unobstructed.

As it was, however, Burgoyne's army reached Saratoga just as the rear of our militia was ascending the opposite bank of the Hudson, where they took post and prevented its passage." Burgoyne, however, although within half an hour's march of Saratoga, gave the surprising order that "the army should bivouac in two lines and await the day."

Mr. Bancroft ascribes this delay to the fact that Burgoyne "was still clogged with his artillery and baggage, and that the night was dark, and the road weakened by rain." But, according to the universal testimony of all the manuscript journals extant, the road, which up to this time was sufficiently strong for the passage of the baggage and artillery trains, became, during the halt, so bad by the continued rain that when the army again moved, at four o'clock in the afternoon, it was obliged to leave behind the tents and camp equipage, which fell most opportunely into the hands of the Americans.

Aside, however, from this, it is a matter of record that the men, through their officers, pleaded with Burgoyne to be allowed to proceed notwithstanding the storm and darkness, while the officers themselves pronounced the delay "madness." But whatever were the motives of the English general, this delay lost him his army, and, perhaps, the British crown her American colonies.

During the halt at Dovogat's, there occurred one of those incidents which relieve with fairer lights and softer tints the gloomy picture of war. Lady Harriet Ackland had, like the Baroness Riedesel, accompanied her husband to America, and gladly shared with him the vicissitudes of campaign life. Major Ackland was a rough, blunt man, but a gallant soldier and devoted husband, and she loved him dearly. Ever since he had been wounded and taken prisoner his wife had been greatly distressed, and it had required all the comforting attentions of the baroness to reassure her.

As soon as the army halted, by the advice of the latter, she determined to visit the American camp and implore the permission of its commander to join her husband, and by her presence alleviate his sufferings.

Accordingly, on the 9th, she requested permission of Burgoyne to depart. " Though I was ready to believe," says that general, " that patience and fortitude in a supreme degree were to be found, as well as every other virtue, under the most tender forms, I was astonished at this proposal.

After so long an agitation of spirits, exhausted not only for want of rest, but absolutely want of food, drenched in rains for twelve hours together, that a woman should be capable of such an undertaking as delivering herself to an enemy, probably in the night, and uncertain of what hands she might fall into, appeared an effort above human nature. The assistance I was enabled to give was small indeed. All I could furnish to her was an open boat, and a few lines, written upon dirty, wet paper, to General Gates, recommending her to his protection." *

- * These "lines" are preserved in the archives of the New

York Historical Society.

In the midst of a driving autumnal storm, Lady Ackland set out at dusk, in an open boat, for the American camp, accompanied by Mr. Brudenell the chaplain, her waiting-maid, and her husband's valet. At ten o'clock they reached the American advanced guard, under the command of Major Henry Dearborn. Lady Ackland herself hailed the sentinel, and as soon as the bateau struck the shore, the party were immediately conveyed into the log-cabin of the major, who had been ordered to detain the flag until the morning, the night being exceedingly dark, and the quality of the lady unknown, Major Dearborn gallantly gave up his room to his guest, a fire was kindled, and a cup of tea provided, and as soon as Lady Ackland made herself known, her mind was relieved from its anxiety by the assurance of her husband's safety.

I visited," says Adjutant-General Wilkinson, "the guard before sunrise. Lady Ackland's boat had put off, and was floating down the stream to our camp, where General Gates, whose gallantry will not be denied, stood ready to receive her with all the tenderness and respect to which her rank and condition gave her a claim. Indeed, the feminine figure, the benign aspect, and polished manners of this charming woman were alone sufficient to attract the sympathy of the most obdurate; but if another motive could have been wanting to inspire respect, it was furnished by the peculiar circumstances of Lady Harriet, then in that most delicate situation which can not fall to interest the solicitudes of every being possessing the form and feelings of a man."

On the evening of the 9th the main portion of the drenched and weary army forded Fish Creek, waist deep, and bivouacked in a wretched position in the open air on the opposite bank. Burgoyne remained on the south side of the creek, with Hamilton's brigade as a guard, and passed the night in the mansion of General Schuyler. The officers slept on the ground with no other covering than oil-cloth. Nor did their wives fare better.

"I was wet says the Baroness Riedesel, "through and through by the frequent rains, and was obliged to remain in this condition the entire night, as I had no place whatever where I could change my linen. I therefore seated myself before a good fire and undressed my children, after which we laid down together upon some straw. I asked General Phillips. who came up to where we were, why we did not continue our retreat while there was yet time, as my husband had pledged himself to cover it, and bring the army through. 'Poor woman,' answered he, 'I am amazed at you. Completely wet through, have you still the courage to wish to go further in this weather? Would that you were our commanding general! He halts because he is tired, and intends to spend the night here, and give us a supper.'"

Burgoyne, however, would not think of a further advance that night; and while his army were suffering from cold and hunger, and every one was looking forward to the immediate future with apprehension, "the, illuminated mansion of General Schuyler," says the Brunswick journal, "rang with singing, laughter, and the jingling of glasses. There Burgoyne was sitting with some merry companions at a dainty supper, while the Champagne was flowing.

Near him sat the beautiful wife of an English commissary, his mistress. Great as the calamity was, the frivolous general still kept up his orgies. Some were even of opinion that he had merely made that inexcusable stand for the sake of passing a merry night. Riedesel thought it his duty to remind his general of the danger of the halt, but the latter returned all sorts of evasive answers."

This statement is corroborated by the Baroness Riedesel, who also adds: "The following day General Burgoyne repaid the hospitable shelter of the Schuyler mansion by burning it, with its valuable barns and mills, to the ground, under pretense that he might be better able to cover his retreat, but others say out of mean revenge on the American general."

But the golden moment had fled. On the following morning, the 10th, it was discovered that the Americans, under Fellows, were in possession of the Battenkil, on the opposite side of the Hudson; and Burgoyne, considering it too hazardous to attempt the passage of the river, ordered the army to occupy the same quarters on the heights of Saratoga which they had used on first crossing the river on the 13th of September. At the same time he sent ahead a working party to open a road to Fort Edward, his intention being to continue his retreat along the west bank of the Hudson to the front of that fort, force a passage across, and take possession of the post. Colonel Cochran, however, had already garrisoned it with 200 men, and the detachment hastily fell back upon the camp.

Meanwhile General Gates, who had begun the pursuit at noon of the 10th with his main army, reached the high ground south of Fish Creek at four the same afternoon. The departure of Burgoyne's working party for Fort Edward led him to believe that the entire British army were in full retreat, having left only a small guard to protect their baggage.

Acting upon this impression, he ordered Nixon and Glover, with their brigades, to cross the creek early the next morning under cover of the fog, which at this time of year usually prevails till after sunrise, and attack the British camp.

The English general had notice of this plan, and placing a battery in position, he posted his troops in ambush behind the thickets along the banks of the creek, and concealed also by the fog, awaited the attack, confident of victory. At early daylight Morgan, who had again been selected to begin the action, crossed the creek with his men on a raft of floating logs, and falling in with a British picket, was fired upon, losing a lieutenant and two privates. This led him to believe that the main body of the enemy had not moved; in which case, the creek in his rear, enveloped by a dense fog, and unacquainted with the ground, he felt his position to be most critical.

Meanwhile the whole army advanced as far as the south bank of the creek, and halted. Nixon, however, who was in advance, had already crossed the stream near its confluence with the Hudson, and captured a picket of sixty men and a number of bateaux, and Glover was preparing to follow him, when a deserter from the enemy confirmed the suspicions of Morgan. This was corroborated, a few moments afterward, by the capture of a reconnoitring party of thirty-five men by the advanced guard, under Captain Goodale, of Putnam's regiment, who, discovering them through the fog just as he neared the opposite bank, charged, and took them without firing a gun.

Gates was at this time at his head-quarters, a mile and a half in the rear; and before intelligence could be sent to him, the fog cleared up, and exposed the entire British army under arms. A heavy fire of artillery and musketry was immediately opened upon Nixon's brigade, and they retreated in considerable disorder across the creek.*

- *The precise spot of this retreat is where the bridge

across Fish Creek leads to Victory Mills, about where the

cars stop at Victory Station.

General Learned had in the mean time reached Morgan's corps with his own and Patterson's brigades and was advancing rapidly to the attack in obedience to a standing order issued the day before, that, " in case of an attack against any point, whether in front, flank, or rear, the troops are to fall upon the enemy at all quarters." He had arrived within 200 yards of Burgoyne's battery, and in a few moments more would have been engaged at great disadvantage, when Wilkinson reached him with the news that the right wing, under Nixon, had given way, and that it would be prudent to retreat. The brave old general hesitated to comply.

"Our brethren," said he, "are engaged on the right, and the standing order is to attack."

In this dilemma Wilkinson exclaimed to one of Gate's aids, standing near, "Tell the general that his own fame and the interests of the cause are at hazard -that his presence is necessary with the troops."

Then, turning to Learned, he continued, "Our troops on the right have retired, and the fire you hear is from the enemy. Although I have no orders for your retreat, I pledge my life for the general's approbation."

By this time several field officers had joined the group, and a consultation being held, the proposition to retreat was approved. Scarcely had they faced about, when the enemy, who, expecting their advance, had been watching their movements with shouldered arms, fired, and killed an officer and several men before they made good their retreat.

The ground occupied by the two armies after this engagement resembled a vast amphitheatre, the British occupying the arena, and the Americans the elevated surroundings. Burgoyne's camp, upon the meadows and the heights of Saratoga north of Fish Creek, was fortified, and extended half a mile parallel with the river, most of its heavy artillery being on an elevated plateau northeast of the village of Schuylerville.

On the American side Morgan and his sharp- shooters were posted on still higher ground west of the British, extending along their entire rear. On the east or opposite bank of the Hudson, Fellows, with 3000 men, was strongly intrenched behind heavy batteries, while Gates, with the main body of Continentals, lay on the high ground south of Fish Creek and parallel with it.

On the north, Fort Edward was held by Stark with 2000 men, and between that post and Fort George, in the vicinity of Glenn's Falls, the Americans had a fortified camp ; while from the surrounding country large bodies of yeomanry flocked in and voluntarily posted themselves up and down the river. The " trap " which Riedesel had foreseen was already sprung!

The Americans, impatient of delay, urged Gates to attack the British camp; but that general, now assured that the surrender of Burgoyne was only a question of time, and unwilling needlessly to sacrifice his men, refused to accede to their wishes, and quietly awaited the course of events.

The beleaguered army was now constantly under fire both on its flanks and rear and in front. The outposts were continually engaged with those of the Americans, and many of the patrols, detached to keep up communication between the centre and right wing, were taken prisoners. The captured bateaux were of great use to the Americans, who were now enabled to transport troops across the river at pleasure, and re-enforce the posts on the road to Fort Edward. Every hour the position of the British grew more desperate, and the prospect of escape less.

There was no place of safety for the baggage, and the ground was covered with dead horses that had either been killed by the enemy's bullets or by exhaustion, as there had been no forage for four days. Even for the wounded there was no spot that could afford a safe shelter while the surgeon was binding up their wounds. The whole camp became a scene of constant fighting. The soldier dared not lay aside his arms night or day, except to exchange his gun for the spade when new intrenchments were to be thrown up.

He was also debarred of water, although close to Fish Creek and the river, it being at the hazard of life in the daytime to procure any from the number of sharp-shooters Morgan had posted in trees, and at night he was sure to be taken prisoner if he attempted it. The sick and wounded would drag themselves along into a quiet corner of the woods, and lie down and die upon the damp ground. Nor were they safe even here, since every little while a ball would come crashing down among the trees. The few houses that were at the foot of the heights were nearest to the fire from Fellows's batteries, notwithstanding which the wounded officers and men crawled thither, seeking protection in the cellars.

In one of these cellars the Baroness Riedesel ministered to the sufferers like an angel of help and comfort. She made them broth, dressed their wounds, purified the atmosphere by sprinkling vinegar on hot coals, and was ever ready to perform any friendly service, even those from which the sensitive nature of a woman will recoil.

Once, while thus engaged, a furious cannonade was opened upon the house, under the impression that it was the head-quarters of the English commander.

"Alas!" says Baroness Riedesel, "it harbored none but wounded soldiers or women!" Eleven cannon-balls went through the house, and those in the cellar could plainly hear them crashing through the walls overhead. One poor fellow, whose leg they were about to amputate in the room above, had his other leg taken off by one of these cannonballs in the very midst of the operation. The greatest suffering was experienced by the wounded from thirst, which was not relieved until a soldier's wife volunteered to bring water from the river. This she continued to do with safety, the Americans gallantly witholding their fire whenever she appeared.

Meanwhile order grew more and more lax, and the greatest misery prevailed throughout the entire army. The commissaries neglected to distribute provisions among the troops, and although there were cattle still left, no animal had been killed. More than thirty officers came to the baroness for food, forced to this step from sheer starvation, one of them, a Canadian, being so weak as to be unable to stand. She divided among them all the provisions at hand, and having exhausted her store without satisfying them, in an agony of despair she called to Adjutant-General Petersham, one of Burgoyne's aids, who chanced to be passing at the time, and said to him, passionately, "Come and see for yourself these officers who have been wounded in the common cause, and are now in want of every thing that is due them! It is your duty to make a representation of this to the general."

Soon afterward Burgoyne himself came to the Baroness Riedesel and thanked her for reminding him of his duty. In reply she apologized for meddling with things she well knew were out of a woman's province; still, it was impossible, she said for her to keep silence when she saw so many brave men in want of food, and had nothing more to give them.

On the afternoon of the 12th Burgoyne held a consultation with Riedesel, Phillips, and the two brigadiers, Hamilton and Gall. Riedesel suggested that the baggage should be left, and a retreat begun on the west side of the Hudson ; and as Fort Edward had been re-enforced by a strong detachment of the Americans, he further proposed to cross the river four miles above that fort, and continue the march to Ticonderoga through the woods, leaving Lake George on the right -- a plan which was then feasible, as the road on the west bank of the river had not yet been occupied by the enemy. This proposition was approved, and an order was issued that the retreat should be begun by ten o'clock that night. But when every thing was in readiness for the march, Burgoyne suddenly changed his mind, and postponed the movement until the next day, when an unexpected manceuvre of the Americans made it impossible. During the night the latter, crossing the river on rafts near the Battenkil, erected a heavy battery on an eminence opposite the mouth of that stream, and on the left flank of the army, thus making the investment complete.

British Surrounded

Burgoyne was now entirely surrounded; the desertions of his Indians and Canadian allies, and the losses in killed and wounded, had reduced his army one-half; there was not food sufficient for five days; and not a word had been received from Clinton. Accordingly, on the 13th, he again called a general council of all his officers, including the captains of companies. The council were not long in deciding unanimously that a treaty should at once be opened with General Gates for an honorable surrender, their deliberations being doubtless hastened by several rifle-balls perforating the tent in which they were assembled, and an 18-pound cannon-ball sweeping across the table at which Burgoyne and his generals were seated.

The following morning, the 14th, Burgoyne proposed a cessation of hostilities until terms of capitulation could be arranged. Gates demanded an unconditional surrender, which was refused; but he finally agreed, on the 15th, to more moderate terms, influenced by the possibility of Clinton's arrival at Albany. During the night of the 16th a Provincial officer arrived unexpectedly in the British camp, and stated that he had heard through a third party, that Clinton had captured the forts on the Hudson Highlands, and arrived at Esopus eight days previously, and further, that by this time he was very likely at Albany.

Burgoyne was so encouraged by this news, that, as the articles of capitulation were not yet signed, he resolved to repudiate the informal agreement with Gates. The latter, however, was in no mood for temporizing, and being informed of the new phase of affairs, he drew up his troops in order of battle at early dawn of the next day, the 17th, and informed him in plain terms that he must either sign the treaty or prepare for immediate battle. Riedesel and Phillips added their persuasions, representing to him that the news just received was mere hearsay, but even if it were true, to recede now would be in the highest degree dishonorable. Burgoyne thereupon yielded a reluctant consent, and the articles of capitulation were signed at nine o'clock the same morning.

They provided that the British were to march out with the honors of war, and to be furnished a free passage to England under promise of not again serving against the Americans. These terms were not carried out by Congress, which acted in the matter very dishonorably, and most of the captured army, with the exception of Burgoyne, Riedesel, Phillips, and Hamilton, were retained as prisoners while the war lasted. The Americans obtained by this victory, at a very critical period, an excellent train of brass artillery, consisting of forty-two guns of various calibre, 4647 muskets, 400 sets of harness and a large supply of ammunition.

The prisoners numbered 5804, and the entire American force at the time of the surrender, including regulars (Continentals) and militia, was 17,091 effective men.

At eleven o'clock on the morning of the 17th, the royal army left their fortified camp, and formed in line on the meadow just north of Fish Creek, at its junction with the Hudson. Here they left their cannon and small-arms. With a longing eye the artillery-man looked for the last time upon his faithful gun, parting with it as from his bride, and that forever. With tears trickling down his bronzed cheeks, the bearded grenadier stacked his musket to resume it no more. Others in their rage, knocked off the butts of their arms, and the drummers stamped their drums to pieces.

Immediately after the surrender, the British took up their march for Boston, whence they expected to embark, and bivouacked the first night at their old encampment at the foot of the hill where Fraser was buried. As they debouched from the meadow, having deposited their arms, they passed between the Continentals, who were drawn up in parallel lines. But on no face did they see exultation.

"As we passed the American army," writes Lieutenant Anbury, one of the captured officers, and bitterly prejudiced against his conquerers, "I did not observe the least disrespect, or even a taunting look, but all was mute astonishment and pity; and it gave us no little comfort to notice this civil deportment to a captured enemy, unsullied with the exulting air of victors."

The English general having expressed a desire to be formally introduced to Gates, Wilkinson arranged an interview a few moments after the capitulation. In anticipation of this meeting, Burgoyne had bestowed the greatest care upon his whole toilet. He had attired himself in full court dress, and wore costly regimentals and a richly decorated hat with streaming plumes. Gates, on the contrary, was dressed merely in a plain blue overcoat, which had upon it scarcely any thing indicative of his rank. Upon the two generals first catching a glimpse of each other, they stepped forward simultaneously, and advanced until they were only a few steps apart, when they halted.

The English general took off his hat, and making a polite bow, said, "The fortune of war, General Gates, has made me your prisoner."

The American general, in reply, simply returned his greeting, and said, "I shall always be ready to testify that it has not been through any fault of your excellency." As soon as the introduction was over, the other captive generals repaired to the tent of Gates, where they were received with the utmost courtesy, and with the consideration due to brave but unfortunate men.

After Riedesel had been presented to Gates, he sent for his wife and children. It is to this circumstance that we owe the portraiture of a lovely trait in General Schuyler's character.

"In the passage through the American camp," the baroness writes, "I observed, with great satisfaction, that no one cast at us scornful glances; on the contrary, they all greeted me, even showing compassion on their countenances at seeing a mother with her little children in such a situation. I confess I feared to come into the enemy's camp, as the thing was so entirely new to me. When I approached the tents, a noble looking man came toward me, took the children out of the wagon, embraced and kissed them, and then, with tears in his eyes, helped me also to alight. He then led me to the tent of General Gates, with whom I found Generals Burgoyne and Philips, who were upon an extremely friendly footing with him. Presently the man, who had received me so kindly, came up and said to me, 'It may be embarrassing to you to dine with all these gentlemen; come now with your children into my tent, where I will give you, it is true, a frugal meal, but one that will be accompanied by the best of wishes.' 'You are certainly,' answered I, 'a husband and a father, since you show me so much kindness.' I then learned that he was the American General Schuyler." *

- * In Randall's Life of Jefferson, we have a picture

of the Riedesels in their temporary Virginia home. As this is

not given in my translation of Madame (Baroness) Riedesel's

Letters, I here quote it in full -- showing, as it does, the personal

appearance of that lady -- to which, she would not, of course,

advert in her "Letters:"

- " General Riedesel rented and lived at Colle, the seat of

Philip Mazzai, a short distance from the eastern base of

Monticello. Himself and theBaroness were frequent visitors of

Mr. Jefferson -- the latter especially, who in every domestic

strait (not an extraordinary thing with an ill-regulated

commissariat and four thousand extra mouths) applied to him

with the freedom of an old neighbor. Her Amazonian stature

and practice of riding like a man, greatly astonished the

Virginian natives; but tradition represents her as a cordial,

warm-hearted, highly intelligent, and, withal, handsome woman,

whose moderate pen. chant for gossip, and not unfrequent

blunders in talking and pronouncing English, only contributed to

the amusingness of her lively conversation. Were we a

racounteur, we could give some specimens of these blunders,

with which in after years Mr. Madison was I wont to set the

table in a roar.'"

The English and German generals dined with the American commander in his tent on boards laid across barrels. The dinner, which was served up in four dishes, consisted only of ordinary viands, the Americans at this period being accustomed to plain and frugal meals. The drink on this occasion was cider, and rum mixed with water. Burgoyne appeared in excellent humor. He talked a great deal, and spoke very flatteringly of the Americans, remarking, among other things, that he admired the number, dress, and discipline of their army, and above all, the decorum and regularity that were observed.

"Your fund of men," he said to Gates, "is inexhaustible; like the Hydra's head, when cut off, seven more spring up in its stead." He also proposed a toast to General Washington -- an attention that Gates returned by drinking the health of the King of England. The conversation on both sides was unrestrained, affable, and free. Indeed, the conduct of Gates throughout, after the terms of the surrender had been adjusted, was marked with equal delicacy and magnanimity, as Burgoyne himself admitted in a letter to the Earl of Derby.

In that letter the captive general particularly mentioned one circumstance, which, he said, exceeded all he had ever seen or read of on a like occasion. It was that when the British soldiers had marched out of their camp to the place where they were to pile their arms, not a man of the American troops was to be seen, General Gates having ordered the whole army out of sight, that not one of them should be a spectator of the humiliation of the British troops. This was a refinement of delicacy and of military generosity and politeness, reflecting the highest credit upon the conqueror.

As the company rose from table, the royal army filed past on their march to the seaboard. Thereupon, by preconcerted arrangement, the two generals stepped out, and Burgoyne, drawing his sword, presented it, in the presence of the two armies, to General Gates. The latter received it with a courteous bow, and immediately returned it to the vanquished general.

Back to Battlegrounds of Saratoga Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com