The year 1778 opened with the brightest prospects for the American cause. The notable success of the American arms on land, and particularly the surrender of Burgoyne, had favorably disposed France toward an alliance with the United States; and, in fact, this alliance was soon formed. Furthermore, the evidence of the prowess of the Americans on shore had stirred up the naval authorities to vigorous action, and it was determined to make the year 1778 a notable one upon the ocean.

The year 1778 opened with the brightest prospects for the American cause. The notable success of the American arms on land, and particularly the surrender of Burgoyne, had favorably disposed France toward an alliance with the United States; and, in fact, this alliance was soon formed. Furthermore, the evidence of the prowess of the Americans on shore had stirred up the naval authorities to vigorous action, and it was determined to make the year 1778 a notable one upon the ocean.

Much difficulty was found, at the very outset, in getting men to ship for service on the regular cruisers. Privateers were being fitted out in every port; and on them the life was easy, discipline slack, danger to life small, and the prospects for financial reward far greater than on the United States men-of-war. Accordingly, the seafaring men as a rule preferred to ship on the privateers. At no time in the history of the United States has the barbaric British custom of getting sailors for the navy by means of the "press-gang" been followed. American bluejackets have never been impressed by force. It is unfortunately true that unfair advantages have been taken of their simplicity, and sometimes they have even been shipped while under the influence of liquor; but such cases have been rare. It is safe to say that few men have ever trod the deck of a United States man-of-war, as members of the crew, without being there of their own free will and accord.

But in 1777 it was sometimes bard to fill the ships' rosters. Then the ingenuity of the recruiting officers was called into play. A sailor who served on the "Protector" during the Revolution thus tells the story of his enlistment:

- "All means were resorted to which ingenuity could devise to induce

men to enlist. A recruiting officer, bearing a flag, and attended by a band of martial music, paraded the streets, to excite a thirst for glory and a spirit of military ambition. The recruiting officer possessed the qualifications necessary to make the service appear alluring, especially to the young. He was a jovial, good-natured fellow, of ready wit and much broad humor. When he espied any large boys among the idle crowd around him, he would attract their attention by singing in a comical manner the following doggerel,

'All you that have bad masters,

And cannot get your due,

Come, come, my brave boys,

And join our ship's crew.'

"A shout and a huzza would follow, and some would join in the ranks. My excitable feelings were aroused. I repaired to the rendezvous, signed the ship's papers, mounted a cockade, and was, in my own estimation, already more than half a sailor. Appeals continued to be made to the patriotism of every young man, to lend his aid, by his exertions on sea or land, to free his country from the common enemy, About the last of February the ship was ready to receive her crew, and was hauled off into the channel, that the sailors might have no opportunity to run away after they were got on board. Upward of three hundred and thirty men were carried, dragged, and driven on board of all kinds, ages, and descriptions, in all the various stages of intoxication, from that of sober tipsiness to beastly drunkenness, with an uproar and clamor that may be more easily imagined than described."

But, whatever the methods adopted to secure recruits for the navy, the men thus obtained did admirable service; and in no year did they win more glory than in 1778.

Capt. Rathburne

As usual the year's operations were opened by an exploit of one of the smaller cruisers. This was the United States sloop-of-war "Providence," a trim little vessel, mounting only twelve four-pounders, and carrying a crew of but fifty men. But she was in command of a daring seaman Capt. Rathburne, and she opened the year's hostilities with an exploit worthy of Paul Jones.

Off the south-eastern coast of Florida, in that archipelago or collection of groups of islands known collectively as the West Indies, lies the small island of New Providence. Here in 1778 was a small British colony. The well-protected harbor, and the convenient location of the island, made it a favorite place for the rendezvous of British naval vessels. Indeed, it bid fair to become, what Nassau is to-day, the chief British naval station on the American coast. In 1778 the little seaport had a population of about one thousand people.

With his little vessel, and her puny battery of four pounders, Capt. Rathburne determined to undertake the capture of New Providence. Only the highest daring, approaching even recklessness, could have conceived such a plan. The harbor was defended by a fort of no mean power. There was always one British armed vessel, and often more, lying at anchor under the guns of the fort. Two hundred of the people of the town were able-bodied men, able to bear arms. How, then, were the Yankees, with their puny force, to hope for success? This query Rathburne answered, "By dash and daring."

It was about eleven o'clock on the night of the 27th of January, 1778, that the "Providence" cast anchor in a sheltered cove near the entrance to the harbor of New Providence. Twenty-five of her crew were put ashore, and being reinforced by a few American prisoners kept upon the island, made a descent upon Fort Nassau from its landward side. The sentries dozing at their posts were easily overpowered, and the garrison was aroused from its peaceful slumbers by the cheers of the Yankee blue-jackets as they came tumbling in over the ramparts. A rocket sent up from the fort announced the victory to the " Providence," and she came in and cast anchor near the fort.

When morning broke, the Americans saw a large sixteen-gun ship lying at anchor in the harbor, together with five sail that looked suspiciously like captured American merchantmen. The proceedings of the night had been quietly carried on, and the crew of the armed vessel had no reason to suspect that the condition of affairs on shore had been changed in any way during the night. But at daybreak a boat carrying four men put off from the shore, and made for the armed ship; and at the same time a flag was run up the flag-staff of the fort, not the familiar scarlet flag of Great Britain, but the almost unknown stars and stripes of the United States.

The sleepy sailors on the armed vessel rubbed their eyes ; and while they were staring at the strange piece of bunting, there came a hail from a boat alongside, and an American officer clambered over the rail. He curtly told the captain of the privateer that the fort was in the hands of the Americans, and called upon him to surrender his vessel forthwith. Resistance was useless ; for the heavy guns of Fort Nassau were trained upon the British ship, and could blow her out of the water.

The visitor's arguments proved to be unanswerable; and the captain of the privateer surrendered his vessel, which was taken possession of by the Americans ; while her crew of forty-five men was ordered into confinement in the dungeons of the fort which had so lately held captive Americans. Other boarding parties were then sent to the other vessels in the harbor, which proved to be American craft, captured by the British sloop-of-war "Grayton."

At sunrise, the sleeping town showed signs of reviving life, and a party of the audacious Yankees marched down to the house of the governor. That functionary was found in bed, and in profound ignorance of the events of the night. The Americans broke the news to him none too gently, and demanded the keys of a disused fortress on the opposite side of the harbor from Fort Nassau. For a time the governor was inclined to demur; but the determined attitude of the Americans soon persuaded him that he was a prisoner, though in his own house, and he delivered the keys. Thereupon the Americans marched through the streets of the city, around the harbor's edge to the fort, spiked the guns, and carrying with them the powder and small-arms, marched back to Fort Nassau.

But by this time it was ten o'clock, and the whole town was aroused. The streets were crowded with people eagerly discussing the invasion. The timid ones were busily packing up their goods to fly into the country; while the braver ones were hunting for weapons, and organizing for an attack upon the fort held by the Americans. Fearing an outbreak, Capt. Rathburne sent out a flag of truce, making proclamation to all the inhabitants of New Providence, that the Americans would do no damage to the persons or property of the people of the island unless compelled so to do in self-defence. This pacified the more temperate of the inhabitants ; but the hotheads, to the number of about two hundred, assembled before Fort Nassau, and threatened to attack it. But, when they summoned Rathburne to surrender, that officer leaped upon the parapet, and coolly told the assailants to come on.

"We can beat you back easily," said he. "And, by the Eternal, if you fire a gun at us, we'll turn the guns of the fort on your town, and lay it in ruins."

This bold defiance disconcerted the enemy; and, after some consultation among themselves, they dispersed.

About noon that day, the British sloop-of-war Grayton made her appearance, and stood boldly into the harbor where lay the "Providence." The United States colors were quickly hauled down from the fort flagstaff, and every means was taken to conceal the true state of affairs from the enemy. But the inhabitants along the waterside, by means of constant signalling and shouting, at last aroused the suspicion of her officers; and she hastily put about and scudded for the open sea. The guns at Fort Nassau opened on her as she passed, and the aim of the Yankee gunners was accurate enough to make the splinters fly. The exact damage done her has, however, never been ascertained.

All that night the daring band of blue-jackets held the fort unmolested. But on the following morning the townspeople again plucked up courage, and to the number of five hundred marched to the fort, and placing several pieces of artillery in battery, summoned the garrison to surrender. The flag of truce that bore the summons carried also the threat, that, unless the Americans laid down their arms without resistance, the fort would be stormed, and all therein put to the sword without mercy.

For answer to the summons, the Americans nailed their colors to the mast, and swore that while a man of them lived the fort should not be surrendered. By this bold defiance they so awed the enemy that the day passed without the expected assault; and at night the besiegers returned to their homes without having fired a shot.

All that night the Americans worked busily, transferring to the "Providence" all the ammunition and stores in the fort; and the next morning the prizes were manned, the guns of the fort spiked, and the adventurous Yankees set sail in triumph. For three days they had held possession of the island, though outnumbered tenfold by the inhabitants; they had captured large quantities of ammunition and naval stores; they had freed their captured countrymen; they had retaken from the British five captured American vessels, and in the whole affair they had lost not a single man. It was an achievement of which a force of triple the number might have been proud.

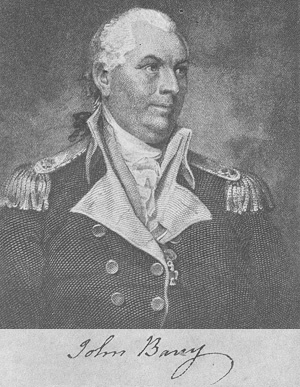

Commmodore Barry

Commmodore Barry

In February, 1778, the Delaware, along the water-front of Philadelphia, was the scene of some dashing work by American sailors, under the command of Capt. John Barry. This officer was in command of the, "Effingham," one of the vessels which had been trapped in the Delaware by the unexpected occupation of Philadelphia by the British. The inactivity of the- vessels, which had taken refuge at Whitehall, was a sore disappointment to Barry, who longed for the excitement and clamors of actual battle. With the British in force at Philadelphia, it was madness to think of taking the frigates down the stream. But Barry rightly thought that what could not be done with a heavy ship might be done with a few light boats.

Philadelphia was then crowded with British troops. The soldiers were well provided with money, and, finding themselves quartered in a city for the winter, led a life of continual gayety. The great accession to the population of the town made it necessary to draw upon the country far and near for provisions ; and boats were continually plying upon the Delaware, carrying provisions to the city. To intercept some of these boats, and to give the merry British officers a taste of starvation, was Barry's plan.

Accordingly four boats were manned with well-armed crews, and with muffled oars set out on a dark night to patrol the river. Philadelphia was reached, and the expedition was almost past the city, when the sentries on one of the British men-of-war gave the alarm. A few scattering shots were fired from the shore; but the jackies bent to their oars, and the boats were soon lost to sight in the darkness. When day broke, Barry was down the river.

Opposite the little post held by the American army, and called Fort Penn, Barry spied a large schooner, mounting ten guns, and flying the British flag. With her were four transport ships, loaded with forage for the enemy's forces. Though the sun had risen, and it was broad clay, Barry succeeded in running his boats alongside the schooner; and before the British suspected the presence of any enemy, the blue-jackets were clambering over the rail, cutlass and pistol in hand. There was no resistance. The astonished Englishmen threw down their arms, and rushed below.

The victorious Americans battened down the hatches, ordered the four transports to surrender, on pain of being fired into, and triumphantly carried all five prizes to the piers of Fort Penn. There the hatches were removed; and, the Yankee sailors being drawn up in line, Barry ordered the prisoners to come on deck. When all appeared, it was found that the Yankees had bagged one major, two captains, three lieutenants, ten soldiers, and about a hundred sailors and marines, a very respectable haul for a party of not more than thirty American sailors.

The next day a British frigate and sloop-of-war appeared down the bay. They were under full sail, and were apparently making for Fort Penn, with the probable intention of recapturing Barry's prizes. Fearing that he might be robbed of the fruits of his victory, Barry put the four transports in charge of Capt. Middleton, with instructions to fire them should the enemy attempt to cut them out. In the mean time, he took the ten-gun schooner, and made for the Christiana River, in the hopes of taking her into shallow waters, whither the heavier British vessels could not follow. But, unluckily for his plans, the wind favored the frigate; and she gained upon him so rapidly, that only by the greatest expedition could he run his craft ashore and escape.

Two of the guns were pointed down the main hatch, and a few rounds of round-shot were fired through the schooner's bottom. She sunk quickly; and the Americans pushed off from her side, just as the British frigate swung into position, and let fly her broadside at her escaping foes.

The schooner being thus disposed of, the British turned their attention to the four captured transports at Fort Penn. Capt. Middleton and Capt. McLane, who commanded the American militia on shore, had taken advantage of the delay to build a battery of bales of hay near the piers. The British sloop-of-war opened the attack, but the sharp-shooters in the battery and on the transports gave her so warm a reception that she retired. She soon returned to the attack, but was checked by the American fire, and might have been beaten off, had not Middleton received a mortal wound while standing on the battery and cheering on his men. Dismayed by the fall of their leader, the Americans set fire to the transport and fled to the woods, leaving the British masters of the field.

Barry's conduct in this enterprise won for him the admiration of friend and foe alike. Sir William Howe, then commander-in-chief of the British forces in America, offered the daring American twenty thousand guineas and the command of a British frigate, if he would desert the service of the United States.

"Not the value and command of the whole British fleet," wrote Barry in reply, "can seduce me from the cause of my country."

After this adventure, Barry and his followers made their way through the woods back to Whitehall, where his ship the "Effingham" was lying at anchor. Here he passed the winter in inactivity. At Whitehall, and near that place, were nearly a dozen armed ships, frigates, sloops, and privateers. All had fled thither for safety when the British took possession of Philadelphia, and now found themselves caught in a trap. To run the blockade of British batteries and men-of-war at Philadelphia, was impossible; and there was nothing to do but wait until the enemy should evacuate the city.

But the British were in no haste to leave Philadelphia; and when they did get ready to leave, they determined to destroy the American flotilla before departing. Accordingly on the 4th of May, 1778, the water-front of the Quaker City was alive with soldiers and citizens watching the embarkation of the troops ordered against the American forces at Whitehall. On the placid bosom of the Delaware floated the schooners "Viper " and "Pembroke," the galleys "Hussar," "Cornwallis," Ferret," and "Philadelphia," four gunboats, and eighteen flat-boats.

Between this fleet and the shore, boats were busily plying, carrying off the soldiers of the light infantry, seven hundred of whom were detailed for the expedition. It was a holiday affair. The British expected little fighting; and with flags flying, and bands playing, the vessels started up stream, the cheers of the soldiers on board mingling with those on the shore.

Bristol, the landing-place chosen, was soon reached; and the troops disembarked without meeting with any opposition. Forming in solid column, the soldiers took up the march for Whitehall; but, when within five miles of that place, a ruddy glare in the sky told that the Americans had been warned of their coming, and had set the torch to the shipping. When the head of the British column entered Whitehall, the two new American frigates "Washington " and " Effingham " were wrapped in flames. Both were new vessels, and neither had yet taken on board her battery. Several other vessels were lying at the wharves ; and to these the British set the torch, and continued their march, leaving the roaring flames behind them.

A little farther up the Delaware, at the point known as Crosswise Creek, the large privateer "Sturdy Beggar " was found, together with several smaller craft. The crews had all fled, and the deserted vessels met the fate of the other craft taken by the invaders. Then the British turned their, steps homeward, and reached Philadelphia, after having burned almost a score of vessels, and fired not a single shot.

On the high seas during 1778 occurred several notable naval engage. ments. Of the more important of these we have spoken in our accounts of the exploits of Tucker, Biddle, and Paul Jones. The less important ones must be dismissed with a hasty word.

It may be said, that, in general, the naval actions of 1778 went against the Americans. In February of that year the "Alfred " was captured by a British frigate, and the "Raleigh " narrowly escaped. In March, the new frigate "Virginia," while beating out of Chesapeake Bay on her very first cruise, ran aground, and was captured by the enemy. In September, the United States frigate "Raleigh," when a few days out from Boston, fell in with two British vessels, one a frigate, and the other a ship-of-the-line. Capt. Barry, whose daring exploits on the Delaware we have chronicled, was in command of the " Raleigh," and gallantly gave battle to the frigate, which was in the lead. Between these two vessels the conflict raged with great fury for upwards of two hours, when the fore-topmast and mizzen top- gallant-mast of the American having been shot away Barry attempted to close the conflict by boarding.

The enemy kept at a safe distance, however; and his consort soon coming up, the Americans determined to seek safety in flight. The enemy pursued, keeping up a rapid fire; and the running conflict continued until midnight. Finally Barry set fire to his ship, and with the greater part of his crew escaped to the nearest land, an island near the mouth of the Penobscot. The British immediately boarded the abandoned ship, extinguished the flames, and carried their prize away in triumph.

To offset these reverses to the American arms, there were one or two victories for the Americans, aside from those won by Paul Jones, and the exploits of privateers and colonial armed vessels, which we shall group to-ether in a later chapter. The first of these victories was won by an army officer, who was later transferred to the navy, and won great honor in the naval service.

In an inlet of Narragansett Bay, near Newport, the British had anchored a powerful floating battery, made of the dismasted hulk of the schooner "Pigot," or which were mounted twelve eight-pounders and ten swivel guns. It was about the time that the fleet sent by France to aid the United States was expected to arrive ; and the British had built and placed in position this battery, to close the channel leading to Newport. Major Silas Talbot, an army officer who had won renown earlier in the war by a daring but unsuccessful attempt to destroy two British frigates in the Hudson River, by means of fire-ships, obtained permission to lead an expedition for the capture of the "Pigot."

Accordingly, with sixty picked men, he set sail from Providence in the sloop "Hawk," mounting three three-pounders. When within a few miles of the "Pigot," he landed, and, borrowing a horse, rode down and reconnoitred the battery. When the night set in, he returned to the sloop, and at once weighed anchor and made for the enemy. As the "Hawk" drew near the "Pigot," the British sentinels challenged her, and receiving no reply, fired a volley of musketry, which injured no one. On came the "Hawk," under full spread of canvas. A kedge-anchor had been lashed to the end of her bowsprit; and, before the British could reload, this crashed through the boarding nettings of the "Pigot," and caught in the shrouds., The two vessels being fast, the Americans, with ringing cheers, ran along the bowsprit, and dropped on the deck of the "Pigot."

The surprise was complete. The British captain rushed on deck, clad only in his shirt and drawers, and strove manfully to rally his crew. But as the Americans, cutlass and pistol in hand, swarmed over the taffrail, the surprised British lost heart, and fled to the hold, until at last the captain found himself alone upon the deck. Nothing was left for him but to surrender with the best grace possible; and soon Talbot was on his way back to Providence, with his prize and a shipful of prisoners.

But perhaps the greatest naval event of 1778 in American waters was the arrival of the fleet sent by France to co-operate with the American forces, Not that any thing of importance was ever accomplished by this naval force : the French officers seemed to find their greatest satisfaction in maneuvering, reconnoitring, and performing in the most exact and admirable manner all the preliminaries to a battle. Having done this, they would sail away, never firing a gun. The Yankees were prone to disregard the nice points of naval tactics. Their plan was to lay their ships alongside the enemy, and pound away until one side or the other had to yield or sink. But the French allies were strong on tactics, and somewhat weak in dash; and, as a result, there is not one actual combat in which they figured to be recorded.

It was a noble fleet that France sent to the aid of the struggling Americans, twelve ships-of-the-line and three frigates. What dashing Paul Jones would have done, had he ever enjoyed the command of such a fleet, almost passes imagination. Certain it is that he would have wasted little time in formal evolutions. But the fleet was commanded by Count d'Estaing, a French naval officer of honorable reputation.

What he accomplished during his first year's cruise in American waters, can be told in a few words. His intention was to trap Lord Howe's fleet in the Delaware, but he arrived too late. He then followed the British to New York, but was baffled there by the fact that his vessels were too heavy to cross the bar. Thence he went to Newport, where the appearance of his fleet frightened the British into burning four of their frigates, and sinking two sloops-of-war.

Lord Howe, hearing of this, plucked up courage, and, gathering together all his ships, sailed from New York to Newport, to give battle to the French. The two fleets were about equally matched. On the 10th of August the enemies met in the open sea, off Newport. For two days they kept out of range of each other, manoeuvring for the weather-gage ; that is, the French fleet, being to windward of the British, strove to keep that position, while the British endeavored to take it from them. The third day a gale arose; and when it subsided the ships were so crippled, that, after exchanging a few harmless broadsides at long range, they withdrew, and the naval battle was ended.

Such was the record of D'Estaing's magnificent fleet during 1778. Certainly the Americans had little to learn from the representatives of the power that had for years contended with England for the mastery of the seas.

Chapter XIII: Last Years of the War

Back to Bluejackets of 1776 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com