The year 1779 is chiefly known in American naval history as the year in which Paul Jones did his most brilliant service in the Bon Homme Richard." The glory won by the Americans was chiefly gained in European waters. Along the coast of the United States, there were some dashing actions ; but the advantage enerally remained with the British.

Perhaps the most notable naval event of this year, aside from the battle between the " Bon Homme Richard " and the "Serapis," was the expedition sent by the State of Massachusetts against the British post at Castine, on the banks of the Penobscot River. At this unimportant settlement in the wilds of Maine, the British had established a military post, with a garrison of about a thousand men, together with four armed vessels. Here they might have been permitted to remain in peace, so far as any danger from their presence was to be apprehended by the people of New England. But the sturdy citizens of Massachusetts had boasted, that, since the evacuation of Boston, no British soldier had dared to set foot on Massachusetts soil ; and the news of this invasion caused the people of Boston to rise as one man, and demand that the invaders should be expelled.

Accordingly a Joint naval and military expedition was fitted out under authority granted by the Legislature of the State. Congress detailed the United States frigate Warren and the sloops-of-war "Diligence" and "Providence," to head the expedition. The Massachusetts cruisers "Hazard," "Active," and Tyrannicide " represented the regular naval forces of the Bay State ; and twelve armed vessels belonging to private citizens were hired, to complete the armada. The excitement among seafaring men ran high. Every man who had ever swung a cutlass or sighted a gun was anxious to accompany the expedition. Ordinarily it was difficult to ship enough men for the navy; now it was impossible to take all the applicants. It is even recorded that the list of common sailors on the armed ship "Vengeance " included thirty masters of merchantmen, who waived all considerations of rank, in order that they might join the expedition.

To co-operate with the flect, a military force was thought necessary; and accordingly orders were issued for fifteen hundred of the militia of the district of Maine to assemble at Townsend. Brig.-Gen. Sullivan was appointed to the command of the land forces, while Capt. Saltonstall of the "Warren" was made commodore of the fleet.

Punctually on the day appointed the white sails of the American ships were seen by the militiamen at the appointed rendezvous. But when the ships dropped anchor, and the commodore went ashore to consult with the officers of the land forces, he found that but nine hundred of the militiamen had responded to the call. Nevertheless, it was determined, after a brief consultation, to proceed with the expedition, despite the sadly diminished strength of the militia battalions.

Set Sail

On the 23d of July, the fleet set sail from the harbor of Townsend. It was an extraordinary and impressive spectacle. The shores of the harbor were covered with unbroken forests, save at the lower end where a little hamlet of scarce five hundred people gave a touch of civilization to the wild scene. But the water looked as though the commerce of a dozen cities had centred there. On the placid bosom of the little bay floated forty-four vessels. The tread of men about the capstans, the hoarse shouts of command, the monotonous songs of the sailors, the creaking of cordage, and the flapping of sails gave an unwonted turbulence to the air which seldom bore a sound other than the voices of birds or the occasional blows of a woodman's axe. Nineteen vessels-of-war and twenty-five transports imparted to the harbor of Townsend an air of life and bustle to which it had been a stranger, and which it has never since experienced.

The weather was clear, and the wind fair; so that two clays after leaving Townsend the fleet appeared before the works of the enemy, Standing on the quarter-deck of the "Warren," the commodore and the general eagerly scanned the enemy's defences, and after a careful examination were forced to admit that the works they had to carry were no mean specimens of the art of fortification.

The river's banks rose almost perpendicularly from the water-side, and on their crest were perched the enemy's batteries, while on a high and precipitous hill was built a fort or citadel. In the river were anchored the four armed vessels.

Two days were spent by the Americans in reconnoitring the enemy's works ; and on the 28th of July the work of disembarking the troops began, under a heavy fire from the enemy's batteries. The "Warren" and one of the sloops-of-war endeavored to cover the landing party by attacking the batteries; and a spirited cannonade followed, in which the American flag-ship suffered seriously. At last all the militia, together with three hundred marines' were put on shore, and at once assaulted the batteries. They were opposed by about an equal number of well. drilled Scotch regulars, and the battle raged fiercely; the men-of-war in the river covering the advance of the troops by a spirited and well-directed fire. More than once the curving line of men rushed against the fiery front of the British ramparts, and recoiled, shattered by the deadly volleys of the Scotch veterans.

Here and there, in the grass and weeds, the forms of dead men began to be seen. The pitiable spectacle of the wounded, painfully crawling to the rear, began to make the pulse of the bravest beat quicker. But the men of Massachusetts, responsive to the voices of their officers, re-formed their shattered ranks, and charged again and again, until at last, with a mighty cheer, they swept over the ramparts, driving the British out. Many of the enemy surrendered; more fled for shelter to the fort on the hill. The smoke and din of battle died away. There came a brief respite in the bloody strife. The Americans had won the first trick in the bloody game of war.

Only a short pause followed; then the Americans moved upon the fort. But here they found themselves overmatched. Against the towering bastions of the fortress they might hurl themselves in vain. The enemy, safe behind its heavy parapets, could mow down their advancing ranks with a cool and deliberate fire. The assailants had already sacrificed more than a hundred men. Was it wise now to order an assault that might lead to the loss of twice that number?

The hotheads cried out for the immediate storming of the fort; but cooler counsels prevailed, and a siege was decided upon. Trenches were dug, the guns in the outlying batteries were turned upon the fort, and the New Englanders sat down to wait until the enemy should be starved out or until reinforcements might be brought from Boston.

So for three weeks the combatants rested on their arms, glaring at each other over the tops of their breastworks, and now and then exchanging a shot or a casual volley, but doing little in the way ot actual hostilities. Provisions were failing the British, and they began to feel that they were in a trap from which they could only emerge through a surrender, when suddenly the situation was changed, and the fortunes of war went against the Americans.

One morning the "Tyrannicide," which was stationed on the lookout down the bay, was seen beating up the river, under a full press of sail. Signals flying at her fore indicated that she had important news to tell. Her anchor had not touched the bottom before a boat pushed off from her side, and made straight for the commodore's flagship. Reaching the "Warren," a lieutenant clambered over the side, and saluted Commodore Saltonstall on the quarter-deck.

"Capt. Cathcart's compliments, sir," said he, "and five British menof-war are just entering the bay. The first one appears to be the 'Rainbow,' forty-four."

Here was news indeed. Though superior in numbers, the Americans were far inferior in weight of metal. After a hasty consultation, it was determined to abandon the siege, and retreat with troops and vessels to the shallow waters of the Penobscot, whither the heavy men-of-war of the enemy would be unable to follow them. Accordingly the troops were hastily re-embarked, and a hurried flight began, which was greatly accelerated by the appearance of the enemy coming up the river.

The chase did not continue long before it became evident the enemy would overhaul the retreating ships. Soon he came within range, and opened fire with his bow-guns, in the hopes of crippling one of the American ships. The fire was returned; and for several hours the wooded shores of the Penobscot echoed and re-echoed the thunders of the cannonade, as the warring fleets swept up the river.

At last the conviction forced itself on the minds of the Americans, that for them there was no escape. The British were steadily gaining upon them, and there was no sign of the shoal water in which they had hoped to find a refuge. It would seem that a bold dash might have carried the day for the Americans, so greatly did they outnumber their enemies. But this plan does not appear to have suggested itself to Capt. Saltonstall, who had concentrated all his efforts upon the attempt to escape.

When escape proved to be hopeless, his only thought was to destroy his vessels. Accordingly his flagship, the "Warren," was run ashore, and set on fire. The action of the commodore was imitated by the rest of the officers, and soon the banks of the river were lined with blazing vessels. The "Hunter," the "Hampden," and one transport fell into the hands of the British. The rest of the forty-nine vessels -- menof-war, privateers, and transports -- that made up the fleet were destroyed by flames.

It must indeed have been a stirring spectacle. The shores of the Penobscot River were then a trackless wilderness; the placid bosom of the river itself had seldom been traversed by a heavier craft than the slender birch-bark canoe of the red man ; yet here was this river crowded with shipping, the dark forests along its banks lighted up by the glare of two score angry fires. Through the thickets and underbrush parties of excited men broke their way, seeking for a common point of meeting, out of range of the cannon of the enemy. The British, meantime, were striving to extinguish the flames, but with little success ; and before the day ended, little remained of the great Massachusetts flotilla, except the three captured ships and sundry heaps of smouldering timber.

The hardships of the soldiers and marines who had escaped capture, only to find themselves lost in the desolate forest, were of the severest kind. Separating into parties they plodded along, half-starved, with torn and rain-soaked clothing, until finally, footsore and almost perishing, they reached the border settlements, and were aided on their way to Boston. The disaster was complete, and for months its depressing effect upon American naval enterprise was observable.

In observing the course of naval events in 1779, it is noticeable that the most effective work was done by the cruisers sent out by the individual States, or by privateers. The United States navy, proper, did little except what was done in European waters by Paul Jones. Indeed, along the American coast, a few cruises in which no actions of moment occurred, although several prizes were taken, make up the record of naval activity for the year.

In observing the course of naval events in 1779, it is noticeable that the most effective work was done by the cruisers sent out by the individual States, or by privateers. The United States navy, proper, did little except what was done in European waters by Paul Jones. Indeed, along the American coast, a few cruises in which no actions of moment occurred, although several prizes were taken, make up the record of naval activity for the year.

The first of these cruises was that made in April by the ships "Warren," "Queen of France," and "Ranger." They sailed from Boston, and were out but a few clays when they captured a British privateer of fourteen guns. From one of the sailors on this craft it was learned that a large fleet of transports and storeships had just sailed from New York, bound for Georgia. Crowding on all sail, the Americans set out in pursuit, and off Cape Henry overhauled the chase. Two fleets were sighted, one to windward numbering nine sail, and one to leeward made up of ten sail. The pursuers chose the fleet to windward for their prey, and by sharp work succeeded in capturing seven vessels in eight hours. Two of the ships were armed cruisers of twenty-nine and sixteen guns respectively, and all the prizes were heavy laden with provisions, ammunition, and cavalry accoutrements. All were safely taken into port.

In June, another fleet of United States vessels left Boston in search of British game. The "Queen of France " and the "Ranger " were again employed; but the "Warren" remained in port, fitting out for her ill-fated expedition to the Penobscot. Her place was taken by the "Providence," thirty-two. For a time the cruisers fell in with nothing of importance. But one day about the middle of July, as the three vessels lay hove to off the banks of Newfoundland, in the region of perpetual fog, the dull booming of a signal gun was heard. Nothing was to be seen on any side.

From the quarter-deck, and from the cross-trees alike, the eager eyes of the officers and seamen strove in vain to penetrate the dense curtain of gray fog that shut them in. But again the signal gun sounded, then another; and tone and direction alike told that the two reports had not come from the same cannon. Then a bell was heard telling the hour, another, still another; then a whole chorus of bells. Clearly a large fleet was shut in the fog.

About eleven o'clock in the morning the fog lifted, and to their intense surprise the crew of the "Queen of France" found themselves close alongside of a large merchant-ship. As the fog cleared away more completely, ships appeared on every side; and the astonished Yankees found themselves in the midst of a fleet of about one hundred and fifty sail under convoy of a British ship-of-the-line, and several frigates and sloops-of-war. Luckily the United States vessels had no colors flying and nothing about them to betray their nationality: so Capt. Rathburn of the "Queen" determined to try a little masquerading.

Bearing down upon the nearest merchantman, he hailed her; and the following conversation ensued,

"What fleet is this?"

"British merchantmen from Jamaica, bound for London. Who are you?"

"His Majesty's ship "Arethusa,'" answered Rathburn boldly, "from Halifax on cruise. Have you seen any Yankee privateers?"

"Ay, ay, sir," was the response. "Several have been driven out of the fleet."

"Come aboard the 'Arcthusa,' then. I wish to consult with you."

Soon a boat put off from the side of the merchantman, and a jolly British sea-captain confidently clambered to the deck of the "Queen." Great was his astonishment to be told that he was a prisoner, and to see his boat's crew brought aboard, and their places taken by American jackies. Back went the boat to the British ship ; and soon the Americans were in control of the craft, without in the least alarming the other vessels, that lay almost within hail. The " Queen " then made up to another ship, and captured her in the same manner.

But at this juncture Commodore Whipple, in the "Providence," hailed the " Queen," and directed Rathburn to edge out of the fleet before the British men-of-war should discover his true character. Rathburn protested vigorously, pointing out the two vessels he had captured, and urging Whipple to follow his example, and capture as many vessels as he could in the same manner. Finally Whipple overcame his fears, and adopted Rathburn's methods, with such success that shortly after nightfall the Americans left the fleet, taking with them eleven rich prizes. Eight of these they succeeded in taking safe to Boston, where they were sold for more than a million dollars.

In May, 1779, occurred two unimportant engagements, - one off Sandy Hook, in which the United States sloop "Providence" ten guns, captured the British sloop "Diligent," after a brief but spirited engagement ; the second action occurred off St. Kitt's, where the United States brig "Retaliation" successfully resisted a vigorous attack by a British cutter and a brig. The record of the regular navy for the year closed with the cruise of the United States frigates "Deane" and "Boston," that set sail from the Delaware late in the summer. They kept the seas for nearly three months, but made only a few bloodless captures.

The next year opened with a great disaster to the American cause. The Count d'Estaing, after aimlessly wandering up and down the coast of the United States with the fleet ostensibly sent to aid the Americans, suddenly took himself and his fleet off to the West Indics. Sir Henry Clinton soon learned of the departure of the French, and gathered an expedition for the capture of Charleston.

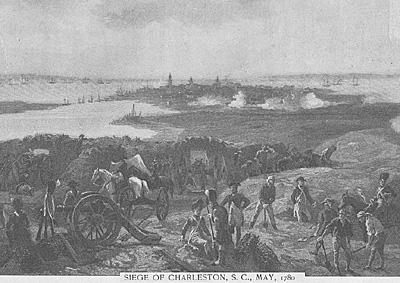

Siege of Charleston

On the 10th of February, Clinton with five thousand troops, and a British fleet under Admiral Arbuthnot, appeared off Edisto Inlet, about thirty miles from Charleston, and began leisurely preparations for an attack upon the city. Had he pushed ahead and made his assault at once, he would have met but little resistance; but his delay of over a month gave the people of Charleston time to prepare for a spirited resistance.

On the 10th of February, Clinton with five thousand troops, and a British fleet under Admiral Arbuthnot, appeared off Edisto Inlet, about thirty miles from Charleston, and began leisurely preparations for an attack upon the city. Had he pushed ahead and made his assault at once, he would have met but little resistance; but his delay of over a month gave the people of Charleston time to prepare for a spirited resistance.

The approach of the British fleet penned up in Charleston harbor several United States men-of-war and armed vessels, among them the "Providence," "Queen of France," "Boston," "Ranger," "Gen. Moultrie," and "Notre Dame." These vessels took an active part in the defence of the harbor against Arbuthnot's fleet, but were beaten back. The "Queen," the "Gen. Moultrie," and the "Notre Dame" were then sunk in the channel to obstruct the progress of the enemy; their guns being taken ashore, and mounted in the batteries on the sea-wall.

Then followed days of terror for Charleston. The land forces of the enemy turned siege guns on the unhappy city, and a constant bombardment was kept up from the hostile fleet. Fort Sumter, the batteries along the water front, and the ships remaining to the Americans answered boldly. But the defence was hopeless. The city was hemmed in by an iron cordon. The hot-shot of the enemy's batteries were falling in the streets, and flames were breaking out in all parts of the town. While the defence lasted, the men-of-war took an active part in it; and, indeed, the sailors were the last to consent to a surrender. So noticeable was the activity of the frigate "Boston" in particular, that, when it became evident that the Americans could hold out but a little longer, Admiral Arbuthnot sent her commander a special order to surrender.

"I do not think much of striking my flag to your present force," responded bluff Samuel Tucker, who commanded the "Boston;" "for I have struck more of your flags than are now flying in this harbor."

But, despite this bold defiance, the inevitable capitulation soon followed. Charleston fell into the hands of the British ; and with the city went the three men-of-war, "Providence," "Boston," and "Ranger."

It will be noticed that this disaster was the direct result of the disappearance of Count d'Estaing and the French fleet. To the student of history who calmly considers the record of our French naval allies in the Revolution, there appears good reason to believe that their presence did us more harm than good. Under De Grasse, the French fleet did good service in co-operation with the allied armies in the Yorktown campaign; but, with this single exception, no instance can be cited of any material aid rendered by it to the American cause. The United States navy, indeed, suffered on account of the French alliance; for despite the loss of many vessels in 1779 and 1780, Congress refused to increase the navy in any way, trusting to France to care for America's interests on the seas. The result of this policy was a notable falling-off in the number and spirit-of naval actions.

The Trumbull

The ship "Trumbull," twenty-eight, one of the exploits of which we have already chronicled, saw a good deal of active service during the last two years of the war; and though she finally fell into the hands of the enemy, it was only because the odds against her were not to be overcome by the most spirited resistance.

It was on the 2d of June, 1780, that the "Trumbull," while cruising far out in the Atlantic Ocean in the path of British merchantmen bound for the West Indies, sighted a strange sail hull down to windward. The "Trumbull" was then in command of Capt. James Nicholson, an able and plucky officer. Immediately on hearing the report of the lookout, Nicholson ordered all the canvas furled, in order that the stranger might not catch sight of the "Trumbull." It is, of course, obvious that a ship under bare poles is a far less conspicuous object upon the ocean, than is the same ship with her yards bung with vast clouds of snowy canvas.

But apparently the stranger sighted the "Trumbull," and had no desire to avoid her; for she bore down upon the American ship rapidly, and showed no desire to avoid a meeting. Seeing this, Nicholson made sail, and was soon close to the stranger. As the two ships drew closer together, the stranger showed her character by firing three guns, and hoisting the British colors.

Seeing an action impending, Nicholson called his crew aft and harangued them, as was the custom before going into battle. It was not a promising outlook for the American ship. She was but recently out of port and was manned largely by "green hands." The privateers had so thoroughly stripped the decks of able seamen, that the "Trumbull" had to ship men who knew not one rope from another; and it is even said, that, when the drums beat to quarters the day of the battle, many of the sailors were suffering from the landsman's terror, seasickness, But what they lacked in experience, they made up in enthusiasm.

With the British flag at the peak, the "Trumbull" bore down upon the enemy. But the stranger was not to be deceived by so hackneyed a device. He set a private signal, and, as the Americans did not answer it, let fly a broadside at one hundred yards distance. The 11 Trumbull " responded with spirit, and the stars and stripes went fluttering to the peak in the place of the British ensign. Then the thunder of battle continued undiminished for two hours and a half.

The wind was light, and the vessels rode on an even keel nearly abreast of each other, and but fifty yards apart. At times their yard-arms interlocked ; and still the heavy broadsides rang out, and the flying shot crashed through bcain and stanchion, striking down the men at their guns, and covering the decks with blood. Twice the flying wads of heavy paper from the enemy's guns set the "Trumbull" afire, and once the British ship was endangered by the same cause.

At last the fire of the enemy slackened, and the Americans, seeing victory within their grasp, redoubled their efforts; but at this critical moment one of the gun-deck officers came running to Nicholson, with a report that the mainmast had been repeatedly hit by the enemy's shot, and was now tottering. If the main-mast went by the board, the fate of the "Trumbull " was sealed. Crowding sail on the other masts, the "Trumbull" shot ahead, and was soon out of the line of fire, the enemy being apparently too much occupied with his own injuries to molest her. Hardly had she gone the distance of a musket-shot, when her main and mizzen top-masts went by the board; and before the nimble jackies could cut away the wreck the other spars followed, until nothing was left but the fore-mast. When the crashing and confusion was over, the "Trumbull" lay a pitiable wreck, and an easy prey for her foe.

But the Briton showed a strange disinclination to take advantage of the opportunity. The Yankee sailors worked like mad in cutting away the wreck; then rushed to their guns, ready to make a desperate, if hopeless, resistance in case of an attack. But the attack never came. Without even a parting shot the enemy went off on her course; and before she was out of sight her main top-mast was seen to fall, showing that she too had suffered in the action.

Not for months after did the crew of the "Trumbull" learn the name of the vessel they had fought. At last it was learned that she was a heavy letter-of-marque, the "Watt." Her exact weight of metal has never been ascertained, though Capt. Nicholson estimated it at thirtyfour or thirty-six guns. The "Trumbull" mounted thirty-six guns. The captain of the "Watt " reported his loss to have been ninety-two in killed and wounded; the loss of the "Trumbull" amounted to thirty-nine, though two of her lieutenants were among the slain. This action, in severity, ranked next to the famous naval duel between the "Bon Homme Richard" and the "Serapis."

As the "Trumbull" fought her last battle under the flag of the United States a year later, and as our consideration of the events of the Revolution is drawing to a close, we may abandon chronological order, and follow Nicholson and his good ship to the end of their career.

In August, 1781, the "Trumbull" left the Delaware, convoying twenty-eight merchantmen, and accompanied by one privateer. Again her crew was weakened by the scarcity of good seamen, and this time Nicholson had adopted the dangerous and indefensible expedient of shipping British prisoners-of-war. There were fifty of these renegades in the crew; and naturally, as they were ready to traitorously abandon their own country, they were equally ready for treachery to the flag under which they sailed. There were many instances during the Revolution of United States ships being manned largely by British prisoners. Usually the crcws thus obtained were treacherous and insubordinate. Even if it had been otherwise, the custom was a bad one, and repugnant to honorable men.

So with a crew half-trained and half-disaffected, the "Trumbull" set out to convoy a fleet of merchantmen through waters frequented by British men-of-war. Hardly had she passed the capes when three British cruisers were made out astern. One, a frigate, gave chase. Night fell, and in the darkness the "Trumbull" might have escaped with her charges, but that a violent squall struck her, carrying away her foretop-mast and main-top-gallant-mast. Her convoy scattered in all directions and by ten o'clock the British frigate had caught up with the disabled American.

The night was still squally, with bursts of rain and fitful flashes of lightning, which lighted up the decks of the American ship as she tossed on the waves. The storm had left her in a sadly disabled condition. The shattered top hamper had fallen forward, cumbering up the forecastle, and so tangling the bow tackle that the jibs were useless. The resail was jammed and torn by the fore-top sail-yard. There was half a (lay's work necessary to clear away the wreck, and the steadily advancing lights of the British ship told that not half an hour could be had to prepare for the battle.

There was no hope that resistance could be successful, but the brave arts of Nicholson and his officers recoiled from the thought of tamely striking the flag without firing a shot. So the drummers were ordered to beat the crew to quarters ; and soon, by the light of the battle-lanterns, captains of the guns were calling over the names of the sailors. The roll-call had proceeded but a short time when it became evident that most of the British renegades were absent from their stations. The officers and marines went below to find them. While they were absent, other renegades, together with about half of the crew whom they tainted with their mutinous plottings, put out the battle-lanterns, and hid themselves deep in the hold. At this moment the enemy came up and opened fire.

Determined to make some defence, Nicholson, sent the few faithful jackies to the guns, and the officers worked side by side with the sailors. The few guns that were manned were served splendidly, and the unequal contest was maintained for over an hour, when a second British man-of-war came up, and the "Trumbull " was forced to strike. At no time had more than forty of her people been at the guns. To this fact is due the small loss of life; for, though the ship was terribly cut up, only five of her crew were killed, and eleven wounded.

The frigate that had engaged the "Trumbull" was the "Iris," formerly the " Hancock " captured from the Americans by the "Rainbow." She was one of the largest of the American frigates, while the "Trum-bull " was one of the smallest. The contest, therefore, would have been unequal, even had not so many elements of weakness contributed to the "Trumbull's" discomfiture.

Taking up again the thread of our narrative of the events of 1780, we find that for three months after the action between the "Trumbull" and the "Watt " there were no naval actions of moment. Not until October did a United States vessel again knock the tompions from her guns, and give battle to an enemy.

During that month the cruiser "Saratoga" fell in with a hostile armed ship and two brigs. The action that followed was brief, and the triumph of the Americans complete. One broadside was fired by the "Saratoga;" then, closing with her foe, she threw fifty men aboard, who drove the enemy below. But the gallant Americans were not destined to profit by the results of their victory; for, as they were making for the Delaware, the British seventyfour "Intrepid" intercepted them, and recaptured all the prizes. The "Saratoga" escaped capture, only to meet a sadder fate ; for, as she never returned to port, it is supposed that she foundered with all on board.

The autumn and winter passed without any further exploits on the part of the navy. The number of the regular cruisers had been sadly diminished, and several were kept blockaded in home ports. Along the American coast the British cruisers fairly swarmed; and the only chance for the few Yankee ships afloat was to keep at sea as much as possible, and try to intercept the enemy's privateers, transports, and merchantmen, on their way across the ocean.

The Alliance

One United States frigate, and that one a favorite ship in the navy, was ordered abroad in February, 1781, and on her voyage did some brave work for her country. This vessel was the "Alliance," once under the treacherous command of the eccentric Landais, and since his dismissal commanded by Capt. John Barry, of whose plucky fight in the " Raleigh " we have already spoken. The "Alliance" sailed from Boston, carrying an army officer on a mission to France. She made the voyage without sighting an enemy. Having landed her passenger, she set out from l'Orient, with the "Lafayette," forty, in company. The two cruised together for three days, capturing two heavy privateers. They then parted, and the "Alliance" continued her cruise alone.

On the 28th of May the lookout reported two sail in sight; and soon the strangers altered their course, and bore down directly upon the American frigate. It was late in the afternoon, and darkness set in before the strangers were near enough for their character to be made out. At dawn all eyes on the "Alliance" scanned the ocean in search of the two vessels, which were then easily seen to be a sloop-of-war and a brig. Over each floated the British colors.

A dead calm rested upon the waters. Canvas was spread on all the ships, but flapped idly against the yards. Not the slightest motion could be discerned, and none of the ships had steerage-way. The enemy had evidently determined to fight; for before the sun rose red and glowing from beneath the horizon, sweeps were seen protruding from the sides of the two ships, and they gradually began to lessen the distance between them and the American frigate. Capt. Barry had no desire to avoid the conflict; though in a calm, the lighter vessels, being manageable with sweeps, had greatly the advantage of the "Alliance," which could only lie like a log upon the water.

Six hours of weary work with the sweeps passed before the enemy came near enough to hail. The usual questions and answers were followed by the roar of the cannon, and the action began. The prospects for the "Alliance" were dreary indeed; for the enemy took positions on the quarters of the helpless ship, and were able to pour in broadsides, while she could respond only with a few of her aftermost guns. But, though the case looked hopeless, the Americans fought on, hoping that a wind might spring up, that would give the good ship "Alliance" at least a fighting chance.

As Barry strode the quarter-deck, watching the progress of the fight, encouraging his men, and looking out anxiously for indications of a wind, a grape-shot struck him in the shoulder, and felled him to the deck.

He was on his feet again in an instant; and though weakened by the pain, and the rapid flow of blood from the wound, he remained on deck, At last, however, he became too weak to stand, and was carried below. At this moment a flying shot carried away the American colors; and, as the fire of the "Alliance" was stopped a moment for the loading of the guns, the enemy thought the victory won, and cheered lustily. But their triumph was of short duration; for a new ensign soon took the place of the vanished one, and the fire of the "Alliance" commenced again.

The "Alliance" was now getting into sore straits. The fire of the enemy had told heavily upon her, and her fire in return had done but little visible damage. As Capt. Barry lay on his berth, enfeebled by the pain of his wound, and waiting for the surgeon's attention, a lieutenant entered.

"The ship remains unmanageable, sir," said he. "The rigging is badly cut up, and there is danger that the fore-top-mast may go by the board. The enemy's fire is telling on the hull, and the carpenter reports two leaks. Eight or ten of the people are killed, and several officers wounded. Have we your consent to striking the colors?"

"No, sir," roared out Barry, sitting bolt upright. "And, if this ship is fought, I will be carried on deck."

The lieutenant returned with his report ; and, when the story became known to the crew, the jackies cheered for their dauntless commander.

"We'll stand by the old man, lads," said one of the petty officers.

"Ay, ay, that we will! We'll stick to him right manfully," was the hearty response.

But now affairs began to look more hopeful for the "Alliance." Far away a gentle rippling of the water rapidly approaching the ship gave promise of wind. The quick eye of an old boatswain caught sight of it.

"A breeze, a breeze" he cried; and the jackies took up the shout, and sprang to their stations at the ropes, ready to take advantage of the coming gust. Soon the breeze arrived, the idly flapping sails filled out, the helmsman felt the responsive pressure of the water as he leaned upon the wheel, the gentle ripple of the water alongside gladdened the ears of the blue-jackcts, the ship keeled over to leeward, then swung around responsive to her helm, and the first effective broadside went crashing into the side of the nearest British vessel. After that, the Conflict was short. Though the enemy had nearly beaten the "Alliance" in the calm, they were no match for her when she was able to maneuver. Their resistance was plucky; but when Capt. Barry came on deck, with his wound dressed, he was just in time to see the flags of both vessels come fluttering to the deck.

The two prizes proved to be the "Atlanta" sixteen, and the "Trepassy" fourteen. Both were badly cut up, and together had suffered a loss of forty-one men in killed and wounded. On the "Alliance" were eleven dead, and twenty-one wounded. As the capture of the two vessels threw about two hundred prisoners into the hands of the Americans, and as the "Alliance" was already crowded with captives, Capt. Barry made a cartel of the "Trepassy," and sent her into an English port with all the prisoners. The "Atlanta" he manned with a prize crew, and sent to Boston; but she unluckily fell in with a British cruiser in Massachusetts Bay, and was retaken.

Once more before the cessation of hostilities between Great Britain and the United States threw her out of commission, did the "Alliance" exchange shots with a hostile man-of-war. It was in 1782, when the noble frigate was engaged in bringing specie from the West Indies. She had under convoy a vessel loaded with supplies, and the two had hardly left Havana when some of the enemy's ships caught sight of them, and gave chase. While the chase was in progress, a fifty-gun ship hove in sight, and was soon made out to be a French frigate.

Feeling that he had an ally at hand, Barry now attacked the leading vessel, and a spirited action followed, until the enemy, finding himself hard pressed, signalled for his consorts, and Barry, seeing that the French ship made no sign of coming to his aid, drew off.

Irritated by the failure of the French frigate to come to his assistance, Barry bore down upon her and hailed, The French captain declared that the maneuvers of the "Alliance" and her antagonist had made him suspect that the engagement was only a trick to draw him into the power of the British fleet. He had feared that the "Alliance" had been captured, and was being used as a decoy; but now that the matter was made clear to him, he would join the "Alliance" in pursuit of the enemy. This he did; but Barry soon found that the fifty was so slow a sailer, that the "Alliance" might catch up with the British fleet and be knocked to pieces by their guns, before the Frenchman got within range.

Accordingly he abandoned the chase in disgust, and renewed his homeward course. Some years later, an American gentle man travelling in Europe met the British naval officer who commanded the frigate which Barry had engaged. This officer, then a vice-admiral declared that he had never before seen a ship so ably fought as with the "Alliance," and acknowledged that the presence of his consorts alone saved him a drubbing.

This engagement was the last fought by the "Alliance" during the Revolution, and with it we practically complete our narrative of the won, of the regular navy during that war. One slight disaster to the American cause alone remains to be mentioned. The "Confederacy," a thirty two gun frigate built in 1778, was captured by the enemy in 1781. She was an unlucky ship, having been totally dismasted on her first cruise and captured by an overwhelming force on her second.

Though this chapter completes the story of the regular navy during the Revolution, there remain many important naval events to be described in an ensuing chapter. The work of the ships fitted out by Congress was aided greatly by the armed cruisers furnished by individual States and privateers. Some of the exploits of these crafts and some desultor,y maritime hostilities we shall describe in the next chapter. And if the story of the United States navy, as told in these few chapters, seem a record of events trivial as compared with the gigantic naval struggles of 1812 and 1861, it must be remembered that not only were naval architecture and ordnance in their infancy in 1776, but that the country was young, and its sailors unused to the ways of war. But that country, young as it was, produced Paul Jones; and it is to be questioned whether any naval war since has brought forth a braver or nobler naval officer, or one more skilled in the handling of a single ship-of-war.

The result of the war of the Revolution is known to all. A new nation was created by it. These pages will perhaps convince their readers that to the navy was due somewhat the creation of that nation. And if to-day, in its power and might, the United States seems inclined to throw off the navy and belittle its importance, let the memory of Paul Jones and his colleagues be conjured up, to awaken the old enthusiasm over the triumphs of the stars and stripes upon the waves.

Chapter XIV: Engaging the Privateers

Back to Bluejackets of 1776 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com