As more and more Japanese soldiers were arriving daily along the Driniumor, long-range Japanese reconnaissance patrols were also sending detailed reports on the American defenses west of the Driniumor. On 19 June, for example, Japanese officer scouts provided precise information about U.S. positions along the Driniumor. Based on that intelligence, Col. Ide Tokutaro, commander of the 80th Infantry Regiment, already deployed near the Driniumor, suggested that his men infiltrate deep into the American

position rather than make a potentially costly frontal assault. General Adachi was thinking in other terms.

As more and more Japanese soldiers were arriving daily along the Driniumor, long-range Japanese reconnaissance patrols were also sending detailed reports on the American defenses west of the Driniumor. On 19 June, for example, Japanese officer scouts provided precise information about U.S. positions along the Driniumor. Based on that intelligence, Col. Ide Tokutaro, commander of the 80th Infantry Regiment, already deployed near the Driniumor, suggested that his men infiltrate deep into the American

position rather than make a potentially costly frontal assault. General Adachi was thinking in other terms.

Eighteenth Army had correctly estimated in mid-June that three U.S. Army infantry battalions were defending the Driniumor, thinly stretched out from the coast to Afua. Adhering to his original May plan for a penetration that would carry all the way to the airfields, Adachi decided to commit the 20th Division and available units of the 41st Division to a frontal attack against the center of the American covering force. Around 30 June, Adachi and his staff arrived at Charov to coordinate final attack preparations with the 20th Division's headquarters staff.

One of Adachi's staff operations officers, Maj. Tanaka Kengoro, had preceded Adachi to Charov in order to conduct a first-hand staff appraisal of the situation. After he had reported his evaluation of the U.S. covering force along the Driniumor and the enemy situation at Aitape to Adachi, Tanaka wondered aloud if the attack against Aitape should be reconsidered. Would the intangibles of battle like morale, unit esprit, fighting spirit-the qualities the Japanese relied so heavily on to compensate for materiel deficiencies suffice to see them through a successful frontal attack on the Aitape defenses? Adachi said nothing, but asked his assembled staff officers to consider the matter.

Next morning Tanaka again told Adachi that the attack should not be launched

as planned. Adachi replied that he had not changed his mind. He would not allow radical alterations in tactical planning to negate the efforts each Japanese unit had made just to reach the Driniumor. [17] Furthermore, the

general's personal notion of officership dictated the attack.

General Adachi's concept of battlefield leadership had its roots in his

understanding of the heroic Japanese military tradition. Death in battle was sufficient reward for faithful service to the emperor. Like most Japanese officers, he was imbued with the spirit of the offensive and therefore always looked for opportunities to attack. Rather than watch his army rot and disintegrate in a passive, defensive role, Adachi felt that even in unfavorable circumstances the more aggressive commander could emerge victorious. He fully understood that the odds against reaching Aitape were heavily against his understrength, poorly supplied troops. But he also was convinced that if troops followed his high standards of leadership and capitalized on enemy mistakes to exploit their initiative, 18th Army could severely damage the U.S. forces near Aitape.

[18]

Already having asked much of his men, Adachi was about to demand more.

The Japanese infantrymen who figured so prominently in General Adachi's plan were nearing the end of their remarkable endurance. Compared to the Japanese soldiers'

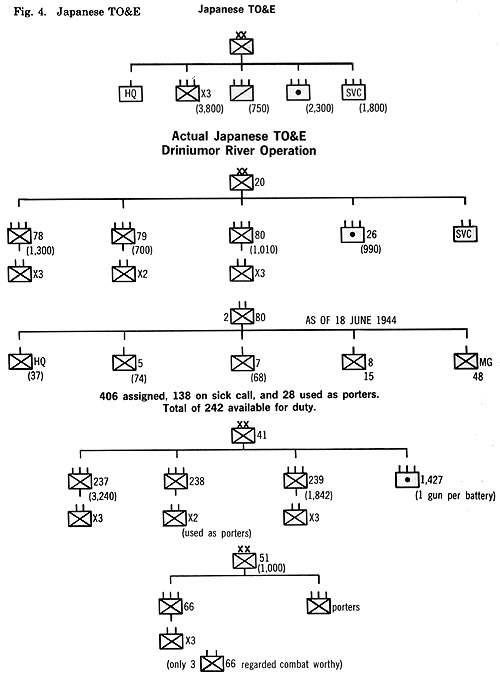

existence, the 112th Cavalry troopers, for all their hardships, lived in luxury. In early July, 18th Army had perhaps 55,000 personnel, including about 3,000 hospitalized. About 15,000 were in the forward combat area, with approximately 5,000 frontline combat troops, 1,500 in the rear echelon, and the remainder filtering into their assembly areas (see fig. 4). They were weary, dirty, and hungry. Rations were meager.

Men of the 3d Battalion, 80th Infantry Regiment, subsisted on rations of less than 330 grams per man per day, supplemented every two or three days by biscuits and once every ten days by cigarettes--three cigarettes to be exact.

For additional nourishment and starches, Japanese ate sago palm leaves. A general lack of essential condiments, especially salt, debilitated the Japanese soldiers in the heat. Malnutrition cases became alarmingly commonplace. Medicines were also in short supply, although a few daring transport pilots did fly night missions across the Celebes Sea to drop quinine and surgical alcohol to the beleaguered army.

[19]

Ultra had, of course, alerted General Krueger to 18th Army's plight, perhaps leading him to underestimate the tenacity of his opponent.

Compounding the materiel deficiencies, a command and control problem arose when the staffs of the 20th and 41st divisions were killed during their approach to the Driniumor. On 10 May Lt. Gen. Katakiri Shigeru, 20th Division commander, and his staff departed Hansa Bay for Wewak. Just before their gasoline-powered landing barge reached Wewak, it struck a floating mine, and all aboard perished. Shortly thereafter, six staff officers attached to Headquarters, 41st Division, died in an Allied bombing attack. Both of Adachi's front-line divisions had to plan and fight with reduced staffs that lacked the extensive planning experience of their late predecessors, a severe impediment to smooth operational planning for the Aitape attack.

[20]

Isolation from normal resupply channels accounted for 18th Army's pitiful condition. Capricious weather and rugged terrain further complicated

the situation. To supply combat forces attacking the Driniumor positions, Adachi had planned to construct a dirt road from Wewak to Aitape, about 130 kilometers, and to employ landing craft to ferry provisions as far west along the coast as Allied interdiction operations would permit. His idea foundered as tropical rainstorms turned the track into a quagmire. The sea route lacked suitable ports and shelters. Beyond those functional concerns, Allied floating mines, PT boat attacks, and air strikes preyed on

Japanese coastal traffic. Finally, Adachi had to resort to human porters, including his precious infantrymen, to manhandle 18th Army's supplies through the jungle. General Yoshihara later estimated that it took six porters per one combat soldier just to maintain the trickle of supplies. [21]

Adachi proceeded with his plan, determined that human spirit could overcome physical obstacles to victory. At 1500 on 3 July, he issued the attack order, the gist of which was:

2. The attack will begin at 2200 on 10 July.

3. The 20th and 41st divisions will attack in column formation, cross the Driniumor, annihilate the American defenders on the covering force, and complete the operation by 12 July.

4. Both divisions will finalize their preparations for the main attack against

Aitape by 15 July [22] . Adachi selected the sector his men would attack based on scouts'

reconnaissance reports. It was about 2,700 meters inland from the coast, across three

small islands in the Driniumor, the largest of which the Japanese called Kawanakajima* (literally, Island in Middle of River).

A patrol report of 1 July outlined the positions of Company L, 127th Battalion, in detail. Scouts estimated that perhaps fifty Americans with one field artillery gun, misidentified as a 105-mm howitzer, held the outpost line. Japanese scouts even pinpointed foxholes occupied by American NCOs on that line.

[23]

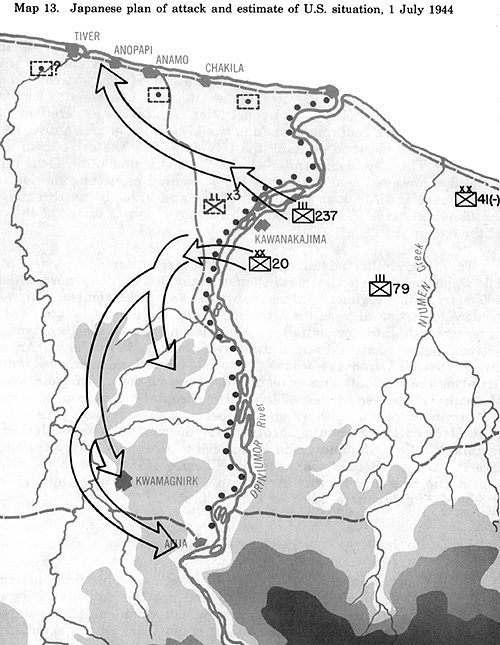

A situation map accompanying Adachi's 3 July attack order dramatically

revealed the efficiency of Japanese patrolling. In early July, 18th Army had a fairly accurate picture of U.S. defenses not only along the Driniumor, but also to Chinapelli and beyond. The key Japanese assumption was that three American infantry battalions held the Driniumor line (see map 13).

The two divisions that would make the attack, the 20th and 41st, adapted their tactics to conform to 18th Army's original concept of breaking through on a narrow front, regrouping, and continuing the attack towards Aitape. The division staff officers, however, privately wondered whether a breakthrough in the center of three widely dispersed enemy infantry battalions would enable them to destroy those foes. The extreme frontage of the U.S. defenses could conceivably isolate the Japanese attackers in

the narrow corridor of their planned penetration. At least one operations officer felt that an attack south against Afua would be a better alternative, because the Japanese could then outflank the U.S. defenders and drive them toward the sea. [24]

The new commander of the 20th Division, Maj. Gen. Miyake Sadahiko,

however, said flatly that the worsening physical condition of his troops made it difficult to conduct the long and arduous march entailed in the flanking attack. He concurred with Adachi's plan to attack at the center of the enemy line.

[25]

There were other advantages to such a straightforward plan of attack. The Japanese expected to mass their battalions on a very narrow, 300- to 500-meter front, regiments abreast in three-deep echelonment. This simple tactical formation allowed them to concentrate the limited firepower of their understrength infantry battalions and

also permitted the commanders to exercise better command and control over their

respective units. An attack on an extended frontage would preclude Japanese

company commanders (let alone those at battalion or regiment) from such control of their maneuver elements. The inherent risk of the narrow frontal attack was that massed infantrymen crossing a river offered themselves as densely packed targets that alert defenders could hardly miss. Success thus depended on two factors.

Second, Japanese intelligence efforts had to identify and report the presence of any American units reinforcing the Driniumor defenses. The Japanese failed on both counts.

1. The 18th Army will attack the enemy occupying the Driniumor River,

drive back the enemy in the Paup and Afua vicinities, and then advance to the Nigia River to prepare for the next or main attack against the enemy's main positions.

*The name also evoked martial sentiments because the Kawanakajima Battlefield in Japan was as well known to Japanese as Gettysburg was to Americans.

First, the Japanese had to achieve tactical surprise by crossing the river in silence.

Chapter 5: Breakthrough to the Driniumor River

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com