“Battle of Britain” (Part 1)

“Lead-Up to Seelowe” (Part 2)

With the benefit of hindsight, many things are clear to the viewer. One can witness the first few snowballs rolling down a hill,

which will become an avalanche, which sweeps through an entire valley. To an observer, seeing things happen in real time, it may

not be clear that this small action is part of something huge and unstoppable.

With the benefit of hindsight, many things are clear to the viewer. One can witness the first few snowballs rolling down a hill,

which will become an avalanche, which sweeps through an entire valley. To an observer, seeing things happen in real time, it may

not be clear that this small action is part of something huge and unstoppable.

In October of 1940, Winston Churchill realised that it was impossible for the Royal Navy to prevent the movement of the formerly French Navy, as they could simply leave their bases on the Biscay coast, and run into the open waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Regular flights by reconnaissance aircraft could only keep track of departures, without much hope of following their tracks.

Further west, long range flying boats, and patrolling Royal Navy ships would have to suffice to track the rapidly dispersing ships, and their vital network of supply vessels. It was therefore decided to prevent any Kriegsmarine vessel from joining their French counterparts, while there was still a chance to deploy overwhelming forces into the North Atlantic, the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay, to intercept and sink the French ships.

The net of British naval vessels, the "picket lines", which stretched from the ice around Greenland, past Iceland, across to the Faeroe Islands, then down to the Shetlands and the Orkneys, was supposed to prevent any vessel leaving the North Sea unnoticed and unchallenged.

The regularly patrolling Cruisers and Destroyers of this force were supplemented by larger, more powerful vessels in the days immediately following the departure of the former French Navy for Atlantic waters.

Regular sorties were sent into the North Sea, running the gauntlet of minefields and Unterseebooten to locate and intercept any German ships, which might attempt to break through the pickets, or attack the coast of England. Many ships of the Kriegsmarine attempted to break out into the North Atlantic, through the line of British warships, and many were forced to turn back, when they came across strong opposition. Many managed to break through the line, however, either by good luck, following storms and moving through the most dangerous areas at night, or by good navigation, and excellent intelligence.

The eyes of the German fleet were not blinded to the movements of the Royal Navy. U-boats and weather ships could observe and report the positions of warships, as could the Luftwaffe, with their long range Focke-Wulf Condor aircraft.

With the information supplied to them by reconnaissance and by a network of spies in Great Britain, the Germans were able to slip many ships through the net. This forced the British to redeploy many of the picket ships to join the searchers of the North Atlantic. Upon receiving the news that the Royal Navy could no longer totally guarantee the safety of the United Kingdom's lifeline - the merchant fleet which plied the Atlantic Ocean, Prime Minister Churchill addressed the House of Commons, telling the assembled members that: "...we must now strengthen our resolve, and redouble our efforts to scour the seas of the threat to the very survival of our nation." DFS Colbert

Continuing Encounters, Mounting Losses

by Christopher Burg and Gavin Bowman

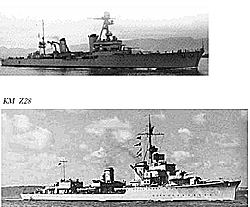

Top: DFS Colbert, Bottom: KM Z28

Top: DFS Colbert, Bottom: KM Z28

[ In order to allow a game involving very little or no strategic map movement, as we are more interested in a quick, easy to set up series of games than a drawn out plotting session, we have divided all of the available ships into battlegroups, and rolled random encounters for each of the areas of conflict: North Atlantic, North Sea and English Channel. We can then take the action directly to the tabletop, without the need for complex hidden map movement. ]

The following report has been assembled from actual battle re ports, from both German and British sources, from radio traffic inter cepts, and from newspapers and wireless services in Neutral countries. Some of the sources used are censored, but all of the information in this column has been confirmed.

Actions in the English Channel, sometime between November 5 and 9, 1940

On November 5, in the semi-darkness after the sun had sunk below the horizon, a Type II U-boat surfaced off the southern coast of England. The U-8, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Hans Börge was on her way to the "hunting grounds" around the coast of Ireland, where convoys dispersed, and it was possible to lie in ambush, and pick targets almost at leisure. Börge had his concerns about the torpedoes with which his boat had been equipped, as for the first year of the war they had been plagued with problems - failing to hit their targets, and even if a hit was scored, more often than not, failing to detonate. As the lookouts gathered on the conning tower, one spotted a brief flash in the darkness, not far off the port beam. The crew scrambled back down through the hatch, and the submarine slid quickly beneath the waves.

Lieutenant Paul Baxter RN was leading his flotilla of Flower Class corvettes back up the channel after a day spent patrolling near Land's End and the Isles of Scilly. It was already dark, and bitterly cold, but they would reach port within a couple of hours or so, as they were stationed at Falmouth.

He scratched at his beard, adjusted the collar of his heavy coat, and looked once more from the open bridge of his small vessel toward the dark sea. He rummag ed in his pocket for his one vice, jammed the heavy old pipe between his teeth, and struck a match to light the tobacco. The f lare of the match seemed shockingly bright amid the darkness of the blacked-out ship, but Baxter knew there was no danger of it being spotted by the enemy, since none could be close enough to see it, not without being seen themselves...

On the morning of November 7, a force of Axis ships departed Brest, seeking a reported Royal Navy patrol of frigates and destroyers, believed to be steaming west past the occupied Channel Islands.

Lurking off the coast, some distance north east of Brest was the submarine HMS Sealion. It was in position as a "watcher" to report any movements of Ger man or French vessels into the English Channel.

It was a misty morning, and the crew could not see very far, but they could hear the engines of several boats moving nearby in the gloom. There were loud voices and horns sounding amid the rumble of engines, and the cries of gulls, and then there was a fishing fleet motoring past them, some of the small trawlers seemingly almost close enough to touch.

As the Captain ordered engines to half ahead, and a new course slightly further north, a new sound was heard. It had not been able to made out amid the racket of the trawlers, it was the sound of much more powerful engines, working hard. As the crew scrambled frantically into the conning tower, there became visible the bow of a destroyer, bearing down on them. Even as the submarine crash dived beneath the cold, green waves, the first of many depth charg es exploded outside the hull.

Soon after dusk on November 9, after its successful sortie, Kapitänleutnant Börge's U-8 was returning to its harbour. It had fired five of its six torpedoes, sunk three oilers, and probably damaged a coastal steamer - though Börge was unsure, as they had rushed that attack because of several other surface craft in the area. One torpedo of the pair fired at it had failed to detonate, but they'd heard the other go off, which meant an eighty- percent success rate - vast improvement on past performances of their torpedoes. They were surfaced, running on diesels, and recharging their batteries, when the lookouts heard the sound of engines disturbing the still night.

The U-boat slid silently under the water, leaving only a periscope protruding, and watched as eight Motor Torpedo Boats of the Royal Navy roared past, chopping the sea to froth and foam with their powerful motors. Once they had departed, U-8 resurfaced, and continued her journey to the south.

Details of actions in the North Atlantic, at sometime between November 3 and 9, 1940

Several days after the attack on Convoy HX-26, by two cruisers - KM Emden and DFS Suffren - and the destroyer Z-24 of the combined Axis fleets, which destroyed the escorting warships and inflicted heavy losses on the merchant vessels, the few surviving merchants began to regroup and head west once more.

Unbeknownst to the regathering merchants, one of the ships seen in the foggy gloom of dawn was not one of their number. A German weather survey ship, the Wassermark - formerly the Dutch cargo vessel Wouterus Lap - had stumbled upon them, and was soon transmitting an encoded signal to inform the Germans of the position, course and speed of the remnants of the badly mauled convoy. The German ship then slipped away into the fog, and was not sighted again by the convoy.

On the night of November 7, off the northeast coast of Ireland, the solitary U-8 ambushed a small convoy, whose escorts had already been detached to meet with another convoy further west. In eight minutes, all three of the torpedoes fired had scored hits and detonated, three oilers were ablaze and sinking. It seemed to the U-boat commander, Kapitänleutnant Börge, that the alterations made to their torpedoes over the last six months had been successful, and that the problems which had plagued them since the start of the war had been entirely resolved. For the British, such news would not be so eagerly received, as now the Germans could rely even more heavily on their deadly "fish".

[Historical Note: The problem of torpedo guidance and faulty detonating pistols had resulted in extremely poor performance in the first year of the war. During the Norwegian campaign - Operation Weserübung - out of thirty-one attacks against warships and transports, not one success was scored.]

During the long night of November 8, a German

battlegroup managed to run through the Iceland / Faeroes

gap, without being intercepted. This powerful force

consisted of the Panzerschiffe KM Lützow, - which had spent

the previous seven months undergoing major repairs for

damage suffered when struck in the stern by a torpedo fired

by the RN submarine Spearfish - the heavy cruiser KM Moltke,

- itself formerly named Lützow - and the destroyers KM

Leberecht Maass (Z-1) and Georg Thiele (Z-2).

0743 on November 9, as dawn broke over the North

Atlantic, a Short Sunderland flying boat, on an anti-U-boat

patrol, spotted the four ships, and their position was

reported.

During the long night of November 8, a German

battlegroup managed to run through the Iceland / Faeroes

gap, without being intercepted. This powerful force

consisted of the Panzerschiffe KM Lützow, - which had spent

the previous seven months undergoing major repairs for

damage suffered when struck in the stern by a torpedo fired

by the RN submarine Spearfish - the heavy cruiser KM Moltke,

- itself formerly named Lützow - and the destroyers KM

Leberecht Maass (Z-1) and Georg Thiele (Z-2).

0743 on November 9, as dawn broke over the North

Atlantic, a Short Sunderland flying boat, on an anti-U-boat

patrol, spotted the four ships, and their position was

reported.

Within an hour and a half the British Task Force "G" consisting of the battleship HMS Revenge, the cruisers HMS Coventry, -with ten 4-inch guns - and Capetown, - armed with 6-inch guns - and the destroyers HMS Hotspur and Havoc, were moving in to intercept. With the weather closing in, the British ships spotted the Germans, and rushed in to attack. At 0922, the Lützow opened fire at long range, quickly zeroing in on the Hotspur, which, with the Havoc, was racing wide in an attempt to close in for a torpedo attack. Within ten minutes of sighting the enemy, three 11-inch shells had hit Hotspur, and she sank completely eight minutes later.

Lützow's gunners changed targets and soon scored a hit on the Coventry, forcing the cruiser to turn away to avoid more fire. As the Revenge closed in, firing at the Lützow, the two German destroyers were heading off the Havoc. They concentrated their fire on the hapless destroyer, quickly scoring a total of seven hits, causing the Havoc to roll over and sink in a matter of minutes.

Lützow and Moltke both concentrated their fire on the approaching battleship, their rate of fire and superior gunnery control giving them an edge, and at 0941, Moltke scored a pair of hits on her, one shell burying itself in the deck, the other tearing through the Revenge's superstructure. Lützow quickly followed suit, an armour-piercing round from one of her main guns destroying the forward range-finder for Revenge's primary battery, and two more rounds lodging in her sidebelt armour, without causing major damage. Revenge's replies to these salvoes splashed all around Moltke, but save some minor splinter damage, she was not troubled by them.

Coventry and Capetown attempted to close in on the German ships again, but were deterred by fire and torpedoes from the two destroyers, Coventry suffering from the brief exchange, taking three hits from the 5-inch armament of the Z-class ships, losing her range finder, and the use of several of her guns. Capetown started making smoke to allow Coventry to withdraw, neither light cruiser having scored a single hit during the thirty-minute engagement. As the cruisers beg an to withdraw, Revenge finally scored a hit on the Moltke, the massive 15-inch shell passing through the lighter ship's upperworks, tearing through the Captain's boat and destroying the port-side crane, but failing to do any severe damage, although it did have the effect of forcing the Moltke to turn away and open the range between the two ships.

Lützow and Moltke continued to fire at the British battleship, and as it too turned away, it was struck by two 11- inch shells from the Panzerschiffe, and two from the heavy cruiser, one of which started a fire abaft the conning tower of the massive ship. With smoke belching from its superstucture, and covered by Capetown's smokescreen, the wounded vessel made for the safety of a squall. As the rapidly worsening weather closed over the combatants, the British ships made good their escape, the Germans content to have seen them off, with minimal damage to their own ships, as they slipped away to the south west, towards the rich merchant-hunting grounds of the Atlantic.

Details of actions in the North Sea, between November 4 and November 10, 1940

Late in the afternoon of November 4, two cruisers slid out of Wilhelmshaven, and entered the North Sea. They were a part of the former French Navy, which had been captured by the Germans after the fall of France and the subsequent armistice. Now the DFS (Deutches Französisch Schiff - German French Ship) Georges Leygues and Montcalm flew the Kriegsmarine Ensign, and their task was to harass the British "picket line" - the patrolling warships stationed to the north and north west of the United Kingdom, there to prevent the Germans passing from the North Sea into the Atlantic Ocean. It was already close to sunset, and there would be little light left after that, so the two vessels steamed unconcerned into the afternoon, heading north.

At the same time, a force of British destroyers, HMS Juno (under Commander Eric Farnsborough), Noble, Noble and Norman, were patrolling into the North Sea, attempting to locate a reported German force of two cruisers, and prevent them from approaching England. Several hours later, in the gathering gloom, with poor visibility, the two forces collided. T hey found themselves to be already in gunnery range, given the poor conditions, and the fact that neither force had spotted the other until they had almost run into each other.

The destroyers, in line astern, closed quickly on the two cruisers, which were surprised by their sudden appearance, and slow to respond to the danger. The first shots from Juno caught Montcalm in the sidebelt, just below the waterline, and aft of her forward turret, tearing a hole in her side, which flooded the forward magazines. Her return fire struck Juno in the deck, just forward of her turrets, and the afthouse, causing severe damage.

Noble had opened fire on Georges Leygues, scoring a hit on the port side, which reportedly caused some damage to the handling room for the secondary 3.5-inch armament. The hit did not, however, prevent the crew from firing the torpedoes on that side of the ship. As the line of Royal Navy destroyers turned away from the cruisers, Noble was struck amidships by a single torpedo, and the resulting explosion tore the little ship in half, and she sank within three minutes. Juno too had launched a volley of ten torpedoes, but as she turned away Montcalm's rear turret fired a devastating salvo, scoring four hits in quick succession, and the Juno was torn apart, as her magazines detonated. The victory was short lived for the crew of the Montcalm, as three of the Juno's torpedoes struck her astern, tearing off the stern, destroying the engine rooms, and causing her to slowly settle, then sink beneath the waves. As the crew of the Montcalm made for the lifeboats, the Georges Leygues turned to flee.

It was now dark, and the two remaining destroyers also turned away, after launching their torpedoes at the retreating cruiser. Half an hour later Georges Leygues returned to pick up the survivors of the Montcalm, and also collected 46 survivors from the two British ships. The two remaining destroyers, HMS Noble and Norman fled north from the site of the encounter, then returned south several hours later, to search for survivors. Finding none after a two-hour search, they then headed west again, bound for the safety of British waters.

The following morning, after they had navigated their way through the minefields of the North Sea, they spotted two ships, well to the south west of their position. The two were closing with them at speed, and it soon became clear that these were the two vessels which had been reported the previous afternoon.

The German cruisers, KM

Seydlitz and Leipzig were returning to the North Sea after

finding it impossible to get through the English Channel to

the Atlantic, due to very clear weather. They would have to

wait for another couple of days to attempt such a bold move,

until the storm promised by the Naval meteorologists closed

in. Just after 0900, a smudge of smoke was sighted on the

horizon, and soon it resolved into two destroyers, making

their way west into a strong headwind.

The German cruisers, KM

Seydlitz and Leipzig were returning to the North Sea after

finding it impossible to get through the English Channel to

the Atlantic, due to very clear weather. They would have to

wait for another couple of days to attempt such a bold move,

until the storm promised by the Naval meteorologists closed

in. Just after 0900, a smudge of smoke was sighted on the

horizon, and soon it resolved into two destroyers, making

their way west into a strong headwind.

The Leipzig headed slightly more north, in order to cut off the two smaller ships, while Seydlitz opened fire with her eight-inch main armament. At 0923, as the Leipzig closed in on the destroyers, Seydlitz scored a pair of hits on the Norman, the heavy shells tearing through the side of the ship, starting several fires, and causing her to list heavily to starboard.

Five minutes later, Noble was hit twice as well, and she too began to list. Leipzig now opened fire, and soon scored a hit on the Noble, putting her forward guns out of commission, and causing her to settle slowly by the bow. Norman took another eight-inch hit, and with fires now raging out of control, the crew took to the boats. Noble was sinking now, having taken another couple of hits from Leipzig, and the German cruiser pulled along side to pick up the survivors, before the two ships moved off, unscathed from the encounter, and returned to Wilhelmshaven.

These are the reports of the second week of encounters in our campaign, and the trend of unfortunate luck for the Royal Navy seems to be continuing… or is it just the legendary Luck Of Gav? Stay tuned for the next instalment…

Losses from the second week of combat were:

British Royal Navy:

6 Destroyers

3 Merchant ships

German Kriegsmarine:

(Hochseeflotte and Deutches Atlantikflotte)

1 6-inch Cruiser

Which brings the total campaign losses to: (drum roll please)

British:

3 Battleships

1 8-inch Cruiser

3 6-inch Cruisers

19 Destroyers

2 Frigates

1 Submarine

Lots of Merchant ships

German:

1 6-inch Cruiser

7 Destroyers

1 Torpedo boat

1 U-boat tender

It should be remembered that although the British losses are far greater than those of the Germans, they do have a much larger navy, which means that they will still be a formidable force… HMS Edinborough sunk

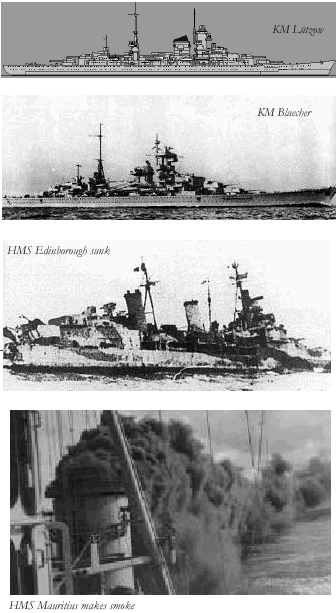

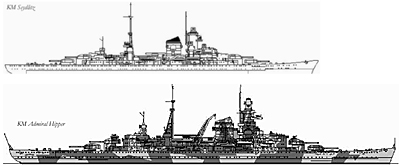

A note on the material illustrating this article

All the fine line drawings of the various Kriegsmarine ships are from Michael Emmerich's site "Kriegsmarine Encyclopaedia" on the German Navy of both wars. at: www.german-navy.de/index.htm Email: emmerich@german-navy.de The site is arguably one of the best on the Net for infor mation on the Kriegsmarine, it's beautifully set out, meticulously organised and copiously illustrated with superb line art (all in colour) and original photographs. Michael is also acknowledged as one of the foremost authorities on the subject. Photographic material on the British Navy comes from another site "WWII Cruiser Operations"on www.world-war.co.uk Email: mike@world-wars.co.uk Again, one of the better of its kind for information on this subject.

More Atlantikubung

-

Part 1: “Battle of Britain” (KS7)

Part 2: “Lead up to Operation Seelowe” (KS9)

Part 3: “Continuing Campaign” (KS10)

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #10

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com