Fortification – the State of the Art in 1885

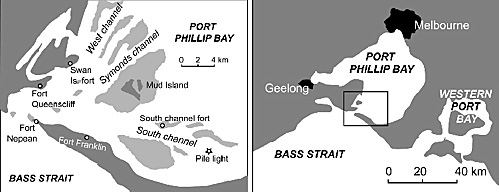

Map 1 – Port Phillip and Westernport Bays

A watershed moment passed in the science of fortification at the bombardment of Alexandria 1881. At this time coast defences bore a close resemblance to the ships. The guns were muzzle-loaders, arranged in long batteries like a broadside, often in two tiers. The improvement of rifled ordnance had called for increased protection, and this was found first by solid constructions of granite, and latterly by massive iron fronts. An example of this type of fortification remains today at Fort Denison in Sydney. This structure sits in the middle of the Harbour. It is of massive rock construction with a tier of guns mounted behind a stone parapet with the somewhat unique inclusion of a Martello tower at one end.

The range of guns being then relatively short, it was necessary to place forts at fairly close intervals, and where the channels to be defended could not be spanned from the shore, massive structures with two or even three tiers of guns, placed as close as on board ship and behind heavy armour, were built up from the ocean bed – again the example of Denison comes to mind, and a similar concept can be seen in the Hobsons Bay gun raft q.v. which was a 68pr mounted on a raft that would presumably be moored off Williamstown.

The bombardment of Alexandria established new applications of old principles by showing the value of concealment and dispersion in reducing the effect of the fire of the fleet. On the old system firing at an iron-fronted fort shot mainly into the brown. If they missed the gun being aimed at, then the one to the right or left was likely to be hit. At Alexandria, however, the Egyptian guns were scattered over a long line of shore, and it was soon found that with the guns and gunners available, hits could only be obtained by running in to short range and dealing with one gun at a time.

Furthermore, the Royal Engineers report submitted following an examination of the forts found that sand embankments had the ability to deflect high velocity ordnance and that sand embankments provided a level of protection far in excess of anything that contemporary military technologists could then conceive. Thus it was that the new Victorian forts found themselves with long glacis of either earth or sand.

The increasing power of defensive artillery meant then that defence installations could be smaller, better concealed and more widely dispersed than before. On the other hand, the ships, too, gained increased range and increased accuracy of fire, so that it became necessary in many cases to advance the general line of the coast defences farther from the harbour or dockyard to be defended, in order to keep the attackers out of range of the objective. In the case of Melbourne, the topography of the Bay meant that a fortuitous “choke point” was available at the entrance that was amenable to fortification while being at the same time a very great distance from the city.

The Fortifications

Table 1 Distribution of guns mounted in the Defence Works of Port Phillip as of 30th June, 1885 (p112, The Colonial Volunteers)

| Location | 9” RML | 80-PR | 68-PR | 40PR BL(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queenscliff | 3 | 4 | - | 2 |

| Nepean | 1 (2) | 4 | - | - |

| Swan Island | - | 3 | - | - |

| Point Franklin | - | 3 | - | - |

| South Channel (3) | 2 | - | - | - |

| Fort Gellibrand | - | 2 | 2 | - |

| Drysdale | - | - | - | 1 |

| Geelong | - | - | - | 1 |

| Williamstown | - | - | - | 1 |

| Victoria Barracks | - | - | - | 1 |

- 1. The 40-pr guns were on field carriages.

2. The 9” gun was placed at Eagles’ Nest, a commanding position outside of Fort Nepean. This was replaced by a 10” BL gun later that same year.

3. 2 x 9” BL and 2 6” BL were later mounted at South Channel as the year drew on. At the time in question only one 9”RML was mounted on a temporary platform on piles. A second was located there a little later from Swan Island, but not until the danger period had passed.

Strategy

The scheme for the defence of Melbourne was determined by the topography of the bay. Port Phillip Bay can only be entered via the Rip, a narrow stretch of dangerous water no more than 3 km wide. Strong positions were thus built at Queenscliff and Point Nepean to bring ships entering the Heads under fire.

West Channel was defended by the battery at Swan Island and a battery was constructed at Point Franklin to deny warships a safe anchorage should they manage to fight their way through South Channel.

The shallower channels would be blocked at wars’ outbreak by hulks purchased for that purpose by the Government and, if time permitted would also be mined. South Channel was to be protected by a minefield consisting (in 1885) if 56 buoyant and 96 ground mines, the latter controlled from stations at South Channel Fort and South Channel Pile Light. South Channel Fort was there to stop any enemy from approaching Melbourne by this only practicable deep-water avenue and to prevent any enemy from attacking the minefield itself.

In a memo dated December 1884, the Naval Commandant Captain A. Brodrick Thomas addressed a memo to F. Sargood, the Minister of Defence. The topic addressed was the best and quickest method for defending Port Phillip, especially the South Channel, keeping in mind that South Channel Fort was then still under construction, and did not mount any guns until the first quarter of 1885.

Concern was raised that the only portion of South Channel that could practicably be mined, was well out of range of any shore-based guns. Following from this was the logical conclusion that South Channel Fort be completed as a matter of urgency. In the meantime the Victorian Fleet would be deployed in such a manner as to defend the minefield.

Captain Thomas goes on to explain the jeopardy an enemy would be in as he passed the Heads: “The better to explain the proposed defence of the port, I will suppose an enemy's ship attempting to enter the Heads and proceeding towards the South Channel at a speed of 13 knots, and show the difficulties she would have to encounter, allowing 3,500 yards to be the effective range of the defending guns... She should be under fire from Nepean fort for one mile, or 4m. 37s. of time. She then comes under fire of the Queenscliff battery, and gradually bearing away for the South Channel, will be under fire of both forts for 4,800 yards, or 11 minutes of time. She is then out of range of Nepean, and a quarter of a mile further off Queenscliff, and comes under fire of the proposed guns at Point Franklin and Point King, for 20 minutes.”

Fleet Deployment

Captain Thomas proposed to dispose of his naval assets thus: “The Cerberus, accompanied by the Victoria and the Albert, would attack the enemy immediately she entered the Heads, who would thus be exposed to an additional fire from four 18-ton guns, one 25-ton gun, one 12-ton gun, and one 4-ton gun, besides small guns and machine-guns. Two of the torpedo boats should accompany the Cerberus, and, under cover of the fire from the ships and forts, attack as opportunities occurred. As soon as their torpedoes were discharged, they should retire at full speed to the Nelson, which would carry spare torpedoes. The boats Batman and Fawkner were to be stationed in rear of the first minefield. The Nelson will be stationed at the east entrance of the South Channel with supplies of spare ammunition, torpedoes, &c., and will be in readiness to assist in defending the minefields. The third torpedo boat will be in reserve with the Nelson.”

Observation and firing stations for the minefields were to be built at South Channel Fort and at the South Channel Pile Light.

The defences of the South Channel made great use of mines, often called torpedoes at the time – what we would call torpedos today, military people in the 1880s would most likely call “locomotive torpedos”. The first field consisted of 42, 500lb observation mines. Observation mines were mines that sat on the sea-bed under observation from a shore station. When an enemy ship passed among them, the observers would detonate the mines.

The second field consisted of 102, 250lb observation mines. The Batman and the Fawkner would commence firing on any enemy who managed to pass the forts at the Heads, overpowering the ships there. These were auxiliary gunboats retained by the government and strengthened forward to take a single 64PR rifled muzzle-loader.

Were the enemy successful in destroying or forcing the first torpedo-field, the gunboats were to retire behind the second torpedo-field where they would act with the Nelson in its’ defence. The reserve torpedo boat and the two others, should they have survived the initial onslaught, would attack targets of opportunity.

It was recognised that the depth of water and strength of the tide at the Heads made difficult defending the entrance to the Bay with observation mines. Captain Thomas then goes on to make reference to a confidential report wherein he discusses using “mechanical mines” in difficult areas such as this as well as in some places in South Channel.

Were war suddenly declared, it was proposed that the West Channel be completely blocked by mechanical mines and other obstructions, such as hulks hat could be purchased by the government and sunk at short notice. Any attempt to destroy these obstructions would have to be undertaken under the fire of Swan Island fort. Electric lights and guard boats would be required at night. It was thought by Captain Thomas that this system of defence would free the Victorian navy and the torpedo corps to concentrate their efforts in the defence of the South Channel.

Captain Thomas further proposed that the fitting out of any small steamers as could be rounded up with spar torpedos would be a valuable addition to the gun defences the military commandant was arranging for the defence of Hobsons Bay, although he would have preferred a Whitehead torpedo boat for special service in Hobson's Bay as a valuable protection.

Should war break out, it was recommend the Government select certain suitable steamers, which, ballasted and protected would be a valuable addition to the naval forces. It was also thought the unarmoured vessels of the Victorian Navy could be easily protected with additional coal filing the compartments around the ships’ machinery.

To War? What if the Russians Came? Defending Melbourne in 1885

- Part 2: Topography

Part 2: Fortifications and the Navy

Part 2: The Fleet

Part 2: Arms and Equipment: Guns

Part 2: Arms and Equipment: Ships

Part 1: Defending Melbourne in 1885

Part 3: Defending Melbourne in 1885: Victorian Military Forces

Back to The Heliograph # 143 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com