There was nothing else for it, they said at the FO and CO.

It had been SIR GARNET's last wish as he stepped on board the transport at Portsmouth to have me at his elbow.

I had promised him to think about it. I had thought about it. I had handed over the chargeof the office to TONY--transferred the Editorial Chair to the oldest contributor--kissed JUDY and embraced our child--bought a solar topee and a Kharkee jacket--detahced from the trophy, of which it forms the central ray, "le sabre, le sabre, le sabre de mon pare," --and to cut a long story short, I was there!

"Push on to the front," said SIR G.; "and see if you can't set things stright with CRETEWAYO."

To hear was to obey. I am not particular about Commissariat or personal comforts. My habit is not to make difficulties, but to overcome them. I waive te tale of my inspannings and outspannings, my struggles over spruits and drifts and dongas, my weary veld-marches, my breakneck kopje-climbs, my gauntlet running of Zulu amuscados, my defiance of all imps of darkness, the impis of deeper darkness still.Enough that I was there, at last--in the black presence--front to front with the formidable son of PANDA. I will not say that my interview had not been facilitated by a letter of my friend and CRETEWAY's worthy of BISHOP C-L-NSO.

"Let me introduce my old friend PUNCH," he wrote concisely. "If anybody can make things straight between you and the English Government, he will. Only listen to what he tells you, and do it."

I have no distinct recollection of how I came into the Royal presence. My recollection on this point is, I own, confused. It could not have been the Caffre beer. I had kept it up late, I know, with the chief poet and head witch-finder, but they assured me there was not a headache in a hundred calabashes; and I was cool, quite cool--in fact, in something like a cold chill--when I was told by a black Chamberlain in cow tail garters, and a court dress of a bead belt and headring, that CRETEWAYO would be glad to hear anything I had to say to him; that I was his father; and that he hoped I would adopt him as my son, and teach him, now that he had washed his spears, how to dry them.

To my astonishment, the Zulu monarch was not alone when I reached his presence. He was surrounded with representatives of all the Powers England had been at odds with during the last twelvemonth. No wonder the kraal of audience was crowded. As I stood there--my topee on my head--I had notified to the Chamberlain that I would no more stoop to take off my hatbefore the Royalty of Ulundi than our Burmese Envoy his shoes before that of a Mandalay--the sabre of my father under my arm, "in act to speak...and graceful waved my hand," I was enabled to identify, on the other side of this estrade which dividied me from my auditors,types of Afghan and Burman, Sclav and Bulgar, Egyptian and Greek, Turk and Skipetar, and Montenegrin--representatives of almost as many races and bloods as there are divisions of opinion in the Irish Home-Rule Party.

To my astonishment, the Zulu monarch was not alone when I reached his presence. He was surrounded with representatives of all the Powers England had been at odds with during the last twelvemonth. No wonder the kraal of audience was crowded. As I stood there--my topee on my head--I had notified to the Chamberlain that I would no more stoop to take off my hatbefore the Royalty of Ulundi than our Burmese Envoy his shoes before that of a Mandalay--the sabre of my father under my arm, "in act to speak...and graceful waved my hand," I was enabled to identify, on the other side of this estrade which dividied me from my auditors,types of Afghan and Burman, Sclav and Bulgar, Egyptian and Greek, Turk and Skipetar, and Montenegrin--representatives of almost as many races and bloods as there are divisions of opinion in the Irish Home-Rule Party.

"And these are the races we have been fighting--or at least quarelling with when we were not fighting!" I thought with pride. "What an illustration of that 'peace' which we have, at least, learnt to reconcile with 'honour'!

My self-congratulations were interrupted by CRETEWAYO springing nimbly to the front, and clashing his assegai against his shield by way of enforcing attention.

"Speak, oh PUNCH!" exclaimed the sable monarch. "What should CRETEWAYO do?"

"CRETEWAYO should listen to the Missionaries England sent him."

"England is very kind. But why send all to CRETEWAYO? Why not keep some at home?"

"We have not left ourselves altogether without reverend counsellors of the same cloth," I replied, "if not the same name."

But if you have Missionaries left at home, why do they not teach you thesame things they teach me? The tell me I must not invade Englishman's country. Englishman invade mine. They forbid me to wash my spear in Boer's blood. Englishman wash his bayonet in Zulus'. They teach me I must not keep up my army of young men. Englishman keeps up his army of men younger than mine. They say I must not kill Zulu. Englishman kill Zulu. I must not take your cattle. You take mine. I must not settle on Englishman or Boer lands. Englishman and Boer settle on my young mens'."

"Hear! Hear!" rang loud from the delighted representatives of hostile or aggrieved Nationalities, who had hung on the thick lips of the sable sovereign.

"Ditto to CRETEWAYO!" they cried with one voice. "Do as you would be done by, and you will not do as you have done."

I found it harder to answer the naked Savage's argument than I had expected; and felt that to go into a detailed reply would be hopeless. But I at once saw a way to short-cut like our own High Commmissioner.

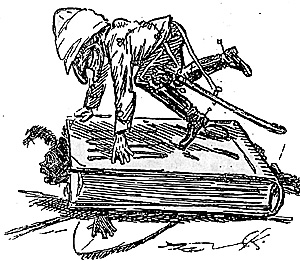

"You will find my answer there!" I answered, pitching right into the face of the Zulu Monarch. It took him unawares, broke down his feeble guard of his cowhide shield, and laid him on his back, prostrate and helpless.

"You will find my answer there!" I answered, pitching right into the face of the Zulu Monarch. It took him unawares, broke down his feeble guard of his cowhide shield, and laid him on his back, prostrate and helpless.

Seizing my opportuinty, I leapt upon the volume, and executing a wild war-dance, strove, with emphatic entrechats, to drive its conetnts into the prostrate Zulu. In the violence of this exertion, I awoke--and lo! it was a dream! And the sound I had heard was the clamour of the Printer's Boy craving "copy" for the Preface.

More Punch: Civil and Military (Lord Chelmsford)

Back to The Heliograph #104 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com