"It is not a question of aiming for Alexandria or even

Sollum," the message read. "I am only asking you to attack the

British forces facing you."

"It is not a question of aiming for Alexandria or even

Sollum," the message read. "I am only asking you to attack the

British forces facing you."

This pleading message from Italy's Benito Mussolini was addressed to his supreme commander in Libya, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, a firmjawed officer with a reputation for reckless offensive spirit -- earned against rebellious Arab tribesmen.

Against the British Western Desert Force, Graziani was far less resolute this 17 July, 1940. He led the numbers game on the Libyan-Egyptian border. His army of 250,000 faced a British force of barely 30,000. Italy fielded 400 guns to the British 150, and 190 fighters to the British 48. 300 Italian tanks faced only 150 British. On paper, Britain had no chance.

Weakness

But behind the numbers and glittering Fascist regalia lurked serious weaknesses that Graziani himself knew. The Italian 10th and 5th Armies in Libya marched on foot, while the British rode in trucks. Two of his six divisions were Blackshirt militia outfits, clad in fancy black uniforms but poor soldiers. His army as a whole was badly trained. Officers strutted about like gigolos, neglecting their men. Italian troops had done badly in Spain against Republicans and badly in Ethiopia against tribesmen. Also, Italian divisions had been reduced from three regiments to two, a paperwork shuffle that created more Italian divisions but weakened their strength.

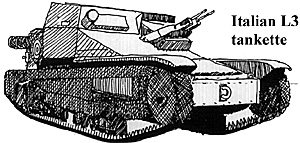

Just as importantly, the Italian forces had poor equipment. Armored cars dated back to 1909. The L3 tank only mounted two machine guns. The underpowered and thinly-armored M11 was little better -- its 37mm gun could not traverse. The heavyweight M13 packed a 47mm gun, but crawled along at nine miles per hour. None could match the British Matilda with its 50mm armor and 40mm gun.

Italian troops were short of antitank guns, antiaircraft guns, ammunition, and radio sets. Artillery was light and ancient.

Sold Off

To ease his balance of payment problems, Mussolini had sold off his newest aircraft and weapons to foreign buyers like Spain and Turkey while equipping his forces with field guns from 1918. The army had borrowed trucks from private firms just to hold peacetime parades of its motorized divisions.

The Beretta pistol and machine gun were outstanding weapons, but the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, 1881 model, suffered from low bullet velocity. Breda machine guns were clumsy to operate and jammed easily. The Model 35 "Red Devil" hand grenades had a cute trick of exploding in the hands of their users.

By comparison, the British troops used the reliable .303 caliber Lee Enfield rifle, the superb Bren and Vickers machine guns, the 25lbr. field artillery piece, and the safe and deadly Mills grenade.

Italian ration packs included pasta meals that had to be cooked in boiling water, which was a scarce commodity in the North African desert, requiring even more water trucks and panniers that Mussolini simply did not have.

Air Comparison

In the air, Graziani could sortie 84 modern bombers and 114 fighters, backed up by 113 obsolescent aircraft. The SavoiaMarchetti SM-79s looked useful. But while the Fiat CR.42 fighter was one of the most maneuverable biplane fighters around, it was completely outclassed by the British Hurricane.

Flying in the desert was tough enough, but while the RAF had great experience at "tropicalising" its aircraft to keep out sand particles, the Italians did not. Both sides' pilots lived in primitive bases that were dust and sand in summer and bog marsh in winter, made up of little shanties created from empty petrol cans and packing cases, suffering from water shortages and fly-infested bully beef. Aircraft often broke down after 30 hours' use. Aviation fuel vaporized in tanks, making it liable to burst in the joints and explode.

Nor would the Italian Navy help. They had no aircraft carriers, were short on fuel and manpower -- submarines were commanded by junior ensigns -- and the British had broken their codes.

But most importantly, Italy was hopelessly outclassed by her British opponents. The British army in Egypt had trained for years in the appalling desert climate. It consisted of crack regiments like the Coldstream Guards and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. The British 7th Armoured Division was its model mobile force, and it was backed up by the 4th Indian Division and the 6'h Australian Division, the elite of both nation's armies.

Finally, both sides were preparing to fight a war in the most inhospitable climate imaginable, Egypt's"Western Desert." This sprawling expanse, occasionally pocked by mud huts or the odd well, was appallingly hot by day, freezing by night. The only paved road ran along the coast' and wasn't finished. Dusty trails crisscrossed the rest. Vehicles that traversed them left their tracks in these trails which are still visible to today's oil explorers.

Doesn't Matter

None of this mattered to the bombastic Mussolini, who so far had thoroughly embarrassed himself in an effort to gain glory for Italy. Afler declaring war on France, his troops had been soundly defeated in the Alps. Another army lay isolated in Ethiopia. ll Duce needed a victory. Graziani was to provide one.

Graziani's answer was to order General Berti's 10th Army, consisting of three corps, to be ready to attack on 27 August. Graziani proposed to send the ill-trained 21st Corps on the northern coast road to Sollum, across the border, while the Libyan Corps and motorized Maletti Group of seven tank battalions would attack on the south side of the escarpment that ran parallel to the sea. The offensive would be backed by 300 aircraft of the 5th Squadron.

Graziani sent these plans to Commando Supremo in Rome, and Mussolini was pleased. However, the Marshal was not actually intending to launch this impressive-sounding attack...it was merely a paper exercise to soothe Il Duce. Graziani lacked transport for the southern swing.

But as soon as Graziani sent his plea for a postponement, Mussolini ordered his vacillating marshal to attack on 9 September or be sacked. Mussolini's son-in-law and Foreign Minister, Galeazzo Ciano, wrote, "Never has a military operation been undertaken so much against the will of the commanders."

Faced with dismissal, Graziani shuffled his plans. The southern swing was abandoned, the Libyan Corps moved near the coast, and the 23rd Corps under General Annibale "Electric Whiskers" Bergonzoli, ordered into the primary attack. The 62nd Marmarican and 63rd Cyrene Divisions, joined by the 1st and 2nd Blackshirt Divisions, would lead the assault.

From the start, the Italian offensive was a bungle. Vehicles' engines overheated. Maletti Group got lost. Radio Rome announced the impending offensive to the world and British intelligence. When Graziani's men finally moved on 10 September, the British 11th Hussars, screening the Italian move, had a good laugh watching Maletti Group try to figure out its location from compasses, speedometers, and maps.

The entire 1st Libyan Division -- including a regiment of paratroopers who gloried in the title, but had never dreamed to jump out of an aircraft -- attacked Sollum, held by a single platoon of Coldstream Guards. The British laid mines and withdrew, fuming the Italian drive into a laborious task of mine-clearing.

British Leadership

The British were led by two brilliant men, Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O'Connor, who commanded the Westem Desert Force, and Gen. Sir Archibald Wavell, supreme commander of Egypt. O'Connor, Anglolrish, was a fommer infantryman who saw the value in tanks and mobility. Wavell, laconic in speech but gifted with the pen, possessed a fluid understanding of desert warfare.

O'Connor, unsmiling, dour, and shabbily dressed, detested publicity of any sort, and was quiet and modest. He was also one of the great commanders of his time.

O'Connor's plan to face Graziani was simple...delaying actions and withdrawals, to drag the Italians beyond their supply line. Then he would counterattack.

Wavell thought the same. The day afler Graziani moved, Wavell ordered O'Connor to prepare plans for a drive on Tobruk. Yet Wavell himself was under siege. The Middle Eastem theater involved highly complex political relations with Arab leaders, a source of endless headaches. Wavell also had responsibility for East Africa, where Mussolini's troops were threatening the Sudan. Palestine had to be policed. Vichy French Syria had to be watched. Wavell's relations with Prime Minister Winston Churchill were cool, and England, bracing for invasion, had little with which to reinforce Wavell.

However, when Wavell promised London unspecified offensive action, the War Offfice sent him 154 tanks, which brought Wavell up to parity with the Italians, along with 48 anti-tank guns, 48 25-lbr. (86mm) field guns, and 500 Bren guns.

It took Graziani's men four days to reach Sidi Barrani, where they stopped, having outrun their supplies, exhausted their infantry, and womrn down their vehicles. Graziani needed to extend the metalled road and water pipeline to his frontline units.

Italian casualties were 120 dead and 410 wounded. The British had lost only 40 men. Radio Rome broadcast that"all is quiet and the trams are again running in the town of Sidi Barrani," which was in fact only a collection of mud huts.

Digging In

Graziani's men began digging in, creating a little string of fortified camps, none of them within range to support each other. Graziani further scattered his tanks among the camps, thus denying himself a mobile reserve.

That was as far as Graziani was prepared to advance. He fired off telegrams to Rome demanding more trucks to haul his supplies. When those were turned down, he sought more trucks than in the whole Italian inventory -- he demanded 600 mules.

On 26 October, Mussolini retorted, "40 days after the capture of Sidi Barrani, I ask myself the question, to whom has this long halt been any use -- to us or to the enemy? I do not hesitate to answer, it has been of use, indeed, more to the enemy...it is time to ask whether you feel you wish to continue in command."

Graziani wired back to say he would resume the offensive on 15 December.

Acceleration

Now events accelerated. On 28 October, Mussolini invaded Greece, hoping as ever for a quick victory. Instead his legions were defeated in the Albanian mountains. Britain had to support its new ally. On 11 November, Royal Navy Swordfish torpedo bombers attacked Taranto, sinking an Italian battleship and damaging two more. The Regia Marina fled to western Italy, taking it out of the North African game. Wavell could now look to the offensive.

O'Connor devised a simple and straightforward five-day raid, called Operation COMPASS, that would take advantage of the spread out Italian forces. Between the 63rd Division's camp at Rabia and Maletti Group at Nibeiwa was the 20-mile undefended Enba Gap. O'Connor planned to pour 4th Indian and 7th Armoured Divisions through it and drive to the sea, thus trapping four Italian divisions. British 16th Brigade, reinforced by a battalion of motorized Free French Marines, would be the anvil of this hammer. Wavell approved the plan without telling O'Connor that as soon as the raid was over, 4th Indian would be withdrawn to Sudan.

Planning was detailed. Thanks to RAF reconnaissance, O'Connor had precise photo-mosaics of Italian vehicle routes, so he knew how to avoid Graziani's mines. To maintain surprise, British leave was not stopped, troops were not given notice of the offensive, forward dumps were called precautionary, and even the medical teams were not advised to expect extra casualties.

Meanwhile, the Italians marked time. Graziani himself helped intrigue to remove the Chief of Staff, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, who resigned on 26 November. A few days later, the 10th Army commander, Gen. Berti, went home to Italy on sick leave, leaving Gen. Gariboldi in field command. That caused command paralysis, as no replacement for Badoglio was assigned until 6 December, when Marshal Ugo Cavallero took over.

British CounterAttack

The next day, O'Connor began his attack with air and naval bombardment of the Italian camps. British surprise was complete. On the morning of 9 December, the British moved forward, troops dragging extra grenades, wearing heavy underwear and woolen sweaters in the cold pre- dawn air.

The advance was almost an anticlimax. The Italians didn't know the British were upon them until they heard the rumble of Matilda tank treads and the plaintive skirl of Scottish bagpipes. 11th Indian Brigade charged into Maleni Group's Nibeiwa Camp, defended by 20 tanks, 12 field guns and 2,500 Libyans. The tanks were caught with their crews at breakfast, and quickly disabled.

"Frightened, dazed or desperate Italians erupted from tents and slit trenches, some to surrender supinely, other to leap gallantly into battle, hurling grenades or blazing machine-guns in futile belabour of the impregnable intruders," wrote G. R. Stevens in his history of 4th Indian Division. "Italian artillerymen gallantly swung their pieces on to the advancing monsters. They fought until return fire from the British tanks stretched them dead or wounded around their limbers. General Maletti, the Italian commander, sprang from his dugout, machine-gun in hand. He fell dead from an answering burst; his son beside him was struck down and captured." More than 2,000 PoWs and 35 tanks were captured...the Indians lost 56 officers and men.

5th Indian Brigade jumped the Tummar Camps from behind, hieing the mostly native 2nd Libyans. At Tummar, Italian artillerymen fought to the last, but their shells bounced off British tanks. Nearly 4,000 Italians were captured, along with considerable wine stocks.

Meanwhile, 7th Armoured's tanks roared up on Buq Buq, held by 64th Division. Soon a British officer radioed, "Up to second 'B' of 'Buq Buq.'" By the end of 10 December, 4th Blackshirt and 1st Libyan Divisions were surrounded, with the British taking Sidi Barrani at 4:40 p.m. The Arabs and paratroopers of Is' Libyans fought hard on the 10th amid a howling sandstorm, but on the 11th the division began to disintegrate. The Leicesters' official history wrote, "A formidable body of men emerging from their trenches...as if in mass attack; but they came stumbling, with their hands up, 2,000 Blackshirts had had enough. A rot had set in."

The disaster fell on the head of Gen. Gallina, who commanded 1st and 2nd Libyan Divisions. His water supply and communications had been cut. "Territory between Sidi Barrani and 2nd Libyan Division infested by mechanized army against which I have no adequate means," he radioed Graziani.

It fell on Mussolini in Rome, too. "News of the attack on Sidi Barani comes like a thunderbolt," wrote Ciano on the 10th."At first it doesn't seem serious, but subsequent telegrams from Graziani confirm that we have had a licking." Mussolini took the news calmly, talking of how it would affect Graziani's prestige.

On the 11th, 2nd Blackshirts and 64th Cantanzaro Division tried to flee, but ran smack into British tanks, and disintegrated.

PoWs

On the same day, O'Connor counted 20,000 PoWs, 180 captured guns, and 60 tanks, for a cost of 600 casualties. 250 of those came from 16th Indian Brigade. RAF Hurricanes had routed Italy's CR 42s, and the remaining Italian forces were in full flight. The obvious thing would be to follow up success.

But as O'Connor sketched his next moves, he received the telegram from Wavell ordering the detachment of 4th Indian to Sudan. 6th Australian Division would replace it, but not right away. That would leave O'Connor with only 16th British Brigade, 7th Armoured (whose tanks needed repair) and Selby Force with its French Marines. Not enough to guard PoWs, collect abandoned vehicles, or provide water for all.

The logical move was to halt the advance -- and Wavell was advising just that.

Instead, O'Connor -- an admirer of Stonewall Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant -- decided to maintain the pace of the offensive.

Pull Out

On the night of the 11th, the Italian 62nd and 63rd Divisions began pulling out under a sandstorm. Graziani finally took action. "Recognizing the impossibility of damming the enemy march on the desert flats, I thought it essential to put to full use the unique natural obstacle at Halfaya, while throwing strong reinforcements into Bardia and Tobruk," he signaled Mussolini. To defend the pass, the only gap in the long escarpment, Graziani threw in an armored brigade and Bergonzoli, a Spanish Civil War veteran whose huge beard was reputed to give off sparks, hence the nickname "Electric Whiskers."

In Rome, Mussolini faced the loss of four divisions, two of them Blackshirts, with remarkable cool. Mussolini "maintains that the many painful days through which we are living must be inevitable in the changing fortunes of every war," Ciano wrote.

While Graziani cut orders from his 60-footdeep Cyrene bunker, O'Connor did the same from his staff car in the desert. 7th Armoured Division was to keep charging. The 3rd Hussars, in their light Mark Vl tanks, tried to do so, but beyond Buq Buq they ran into do so, but beyond Buq Buq they ran into heavy Italian artillery and airpower.

O'Connor called for RAF Gloster Gladiators to intercept, but the biplane fighters were out of action after the exertions of the past few days. O'Connor used his superior 25-lbr. guns, and the offensive, despite the loss of a number of tanks, was on again. 7th Armoured Division rumbled forward, heading for Halfaya Pass and Fort Capuzzo, the white brick fort guarding the Libyan border.

The offensive so far was turning into a lark, with 14,000 PoWs in the bag, cheerfully organizing their journey back to Egyptian cages. The Coldstream Guards reported capturing "five acres of offcers and 200 acres of other ranks." Despite losses of vehicles to gunfire and maintenance, O'Connor's force was riding the crest of a wave, boosting morale back in England.

Raid Extendeed

Now the aggressive O'Connor extended his five-day raid to grab the small Egyptian border port of Sollum, through which the Royal Navy could re-supply him. Then O'Connor could push on to Bardia. The problem was to move 38,000 PoWs and 4th Indian Division back and bring his supplies and 6th Australians up.

The pursuit went on. Western Desert Force was rena~n_d 13th Corps. On the 12th, artillery slowed the British. Exhausted troops drove along in the dark under blackout conditions, wearied by noise, repairs, smoke, heat and cold. Next day, O'Connor stripped 7th Armoured's Support Group of vehicles, so that he had more trucks to keep his tanks topped up with gas.

In his bunker, Graziani showed more vigor with his signals pad than with his army. He wired Rome in a panic, to say that Cyrenaica was lost, recommending retreat to Tripoli, claiming the battle was "a flea against an elephant." Churchill later wrote that "the flea had devoured a large portion of the elephant."

Mussolini said, "Here is another man with whom I cannot get angry, because I despise him."

On 4 December, 7th and 4th Annoured Brigades came under heavy Italian air bombardment. SM 79s ranged unmolested -- Wavell had been forced to send some of his aircraft to Greece. Next day, the British offensive resumed.

In Cyrene, Graziani faced the inevitability of losing Sollum and Fort Capuzzo, and retreated the bulk of his force to Bardia. On the 16th, the British hit Sidi Omar, which was held by 62nd Division, amid minefields and a white stone Beau Geste fort. Lacking infantry,

The unorthodox maneuver worked. The lead tank roared into the center of the fort, where the tank commander traded pistol shots with stunned Italians. Before the defenders could overwhelm the Matilda, its squadron mates arrived, and the Italians collapsed.

By the 20th, 7th Armoured, despite exhausted crews and vehicles, had seized Capuzzo and Sollum, but Bergonzoli had been able to muster a considerable defense in Bardia: four divisions of 21st Corps plus fortress troops, border guards, an anti-tank ditch, concrete blockhouses, and remnants of fleeing units. Altogether Bergonzoli had 45,000 men and 400 guns, and a brigade of M13 tanks. He also had a message from Mussolini, exhorting him to fight to the last.

Against this O'Connor hurled RAF Wellington bombers, three battleships, and HMS Aphis, a gunboat that sank several coasters in Bardia harbor. He also cut loose Maj. Gen. Iven Mackay's 6th Australian Division, the first Diggers to see action in World War II. The division, a mixture of "old sweats" and new volunteers, rode trucks painted with the division's symbol, a leaping kangaroo, to the battle area. The Australians were eager to find out if it was true that Bergonzoli's beard gave offsparks.

The Australians were weighted down with 70 Ibs. of kit per man and restricted to a half-gallon of water per day. A man could shave or wash, but not both."The discomforts the desert imposed were greater than those inflicted by the enemy," the Australian offficial history noted.

McKay planned to assault Bardia with 16th and 17th Brigades, estimating the Italian defenses had only 20,000 men. The valuable armor would prevent the escape of the garrison and move on to Tobruk when Bardia fell. The infantry would drive a wedge through the center of the Italian line, cutting roads, and enabling his men to assault the Italian defenses from behind and annihilate them in detail.

Supplies were still short -- 11,500 sleeveless leather jerkins to keep the Diggers warm didn't arrive until New Year's Day, and 350 wire cutters didn't show up until the next, the night before the attack. 300 pairs of gloves to protect the hands of men cutting wire were handed out as the infantry moved into their assembly areas, but tape to mark attack routes never arrived. 3-inch mortars did, but without sights. A 17th Brigade officer hopped into a jeep and drove all the way to Cairo and back to pick the sights up.

"Tonight is the night," wrote 16 Brigade's official diarist."By this time tomorrow (5 p.m.), the fate of Bardia should be sealed. Everyone is happy, expectant, eager. Old timers say the spirit is the same as in the last war. Each truckload was singing as we drove to the assembly point. The brigade major and party taped the startline -- historic, for it is the start-line of the Australian soldier in this war."

Attack

At 2:30 the Australian troops, looking enormous in jerking, greatcoats, and tin hats, lugging 150 rounds of ammo and three days of bully beef, drank a tot of rum, and moved forward behind a heavy barrage. Engineers led the way with wire cutters and bangalore torpedoes to remove Italian wire. When the torpedoes went off, the Australians charged through the wire.

The intense artillery bombardment thoroughly frightened the 1st Blackshirt Division, whose only combat experience had been beating helpless civilian "enemies of the state" back in Calabria. Now the Fascist "goons" found themselves under heavy shelling, and facing enommous Australian infantrymen at point-blank range. So the Italians surrendered. Some thought the Aussies' leather jerkins were bulletproof.

Australian troops marched at ease through the positions, passing Italian troops waving white cloths. Sgt. Ian Mcintosh of New South Wales, a World War I veteran, led 24 men to capture 3 field guns, an anti-tank gun, 12 machine guns, and 104 PoWs. Lt. A.C. Murchison of Newcastle led a bayonet charge that caused the Italians facing him to surrender. As Murchison moved forward, the surrenders took on a chain reaction, and the Aussies were soon thumbing the Italians back, yelling, "Avant)." The company next to Murchison took 300 PoWs.

"It was now half an hour after midday. By this time an apparently endless column of Italian prisoners was streaming back though the gaps in the perimeter; the officers in ornate uniforms with batmen beside them carrying their suitcases; the men generally dejected and untidy, strangely small beside their captors," wrote the Australian offcial history. "When the 2/5th Battalion, marching into the perimeter, saw this column moving toward them, their first thought was that 16th Brigade was being driven back -- then came the realisation that the close-packed column, winding like a serpent over the flat country, was a sample of a defeated Italian army." By noon 6,000 PoWs were in the cage, and McKay had a rude shock when a PoW officer told him the enemy defenses were 40,000 men.

The battle raged on. Italian artillerymen fought hard, but the Australians had the advantage of mobility, and moved around the gunners, leading to more surrenders. The 2/5th, Australians found a line of L3 tanks, motors running. One quick Bren gun burst and 200 Italians surrendered their little tanks. Sgt. W. T. Morse fired a shot into a wadi's pit and out came 70 Italians, 25 of them officers, waving white flags. It was the headquarters of an artillery outfit. The Australians were stunned to find enameled baths, silk clothing, and cosmetics. Morse saw some heads behind a wall nearby, and found 200 more Italians ready to quit. Overall, the 2/5th took 3,000 PoWs in the wadi.

Now the Australians stormed the Italian outpost line, using machinegun fire and grenades to winkle out the defenders. At Post 22 an Italian leaped up from a pit and shot down Capt. D. L. Green, then dropped his rifle, and surrendered, smiling broadly. A furious Australian threw the Italian down into his post and emptied his Bren gun into him. Another Australian officer intervened to prevent a massacre of other surrendering Italians.

Post 25 was nearby, and the Italians there saw this action. They sent an emissary to surrender. With help of the emissary, Posts 23 and 20 fell in short order.

The 2/3rd ran into six Italian tanks, which opened fire at 30 yards. An Australian ran forward and fired into the turret of one tank with his pistol. The other five moved south and released 500 Italians held prisoner while calling on the Australian guards to give up. Outnumbered, the Australians handed their rifles to their captives. The tanks moved off to find other prey. Just then a nearby Australian Bren gun opened up, and the 500 Italians surrendered again. Fortunately, three British 2-lbr. antitank guns, mounted on trucks, turned up and destroyed the attackers. This was the most vigorous Italian counterattack of the whole battle.

Still, it wasn't all easy. 17th Brigade ran into determined Italian resistance. So did the French marines. By 4 January, the 17th Brigade was scattered, 16th Brigade exhausted. Mackay sent in his reserve, 19th Brigade, for the coup de grace.

Backed by tanks and the Northumberland Fusiliers, the Australians moved in on the town, taking hundreds of PoWs. Italian guns and British tanks traded salvos like battleships at sea, but British mobility defeated Il Duce's forts and posts.

A British tank unit rumbled up to an Italian fort, and charged. When the Italians saw the tanks coming, they opened the gate, and the tanks cruised through a mob of surrendering men. Another platoon walked down a goat track into the town and took thousands of PoWs.

Hordes of Italian support troops tried to hide from the attackers, but were scooped up by Aussies shouting, "Lashay lay armay," a corruption of the Italian phrase "Lascie le arm," which meant, "Lay down your arms." The Italians obeyed, climbing up the goat tracks.

Col. G.W. Eather of the 2/1st Battalion, a future general, was told some Italians had been captured. Thinking it was a dozen or so, he said, "Bring them in." More than 1,500 came in. Eather, embarrassed at the number of his PoWs, told them to come back in the morning.

It was impossible to count the horde -- some Italians meandering across the battlefield were "captured" several times. Among the PoWs bagged by 19th Brigade were the commanding generals of 62nd and 63rd Divisions, Tracchia and Guida, respectively.

While the ground forces advanced, RAF Blenheim bombers blasted Italian airfields to the west, clearing the skies.

Nothing Left

There was nothing left for Bergonzoli but to burn his code books and flee. Meanwhile, his men shamed into captivity, officers clutching swords, while Australians moved into Bardia, and ransacked the Italian stores of wine and clean linen.

The British claimed to have captured 44,868 PoWs, while the Italians estimated their dead at 40,000 and that the British captured 38,000. The victory was smashing. 13th Corps captured twice as many guns as were in its inventory, along with 12 M13 tanks and 113 L3 tankettes, and most importantly, 708 motor vehicles, badly needed to relieve 7th Armoured's exhausted trucks. Australian casualties were 136 dead and 320 wounded.

Australian troops equipped themselves with captured pistols, watches, compasses, gunsights, and signal equipment. "The behaviour of the troops in the face of quantities of liquor was exemplary," the Australian provost marshal noted. However, the Aussies threw away useless Italian rifles and grenades.

The collapse of Bardia left Graziani with only two Italian infantry divisions, 60th Sabratha and 615'Sirte, in Cyrenaica, and four more in Tripolitania. Of the 248,000 Graziani began the campaign with, some 80,000 had been lost.

Now Mussolini was upset. On 12 January, he told Ciano that the Italians were "a race of sheep," adding that, "In the future we shall select an army of professionals, selecting them out of 12 to 13 million Italians there in the valley of the Po and in part of central Italy. All the others will be put to work making arms for the warrior aristocracy."

Graziani himself was also depressed. He sent his wife to Ciano with a letter pleading for the Luftwaffe, blamed the whole mess on Badoglio, and finally talked of suicide.

German Intervention

But Adolf Hitler was looking hard at North Africa, too. On 11 January he ordered German armor be sent to North Africa, and dispatched Luftwaffe Fliegerkorps 10 to Sicily. Germany's Fuhrer did not want to be drawn into a campaign in North Africa, but had to support his ally.

"The success at Bardia demonstrated that there is no fortress so strong in its engineering that men of determination and cunning, with weapons in the their hands, cannot take it," wrote the Australian official history. With Bardia in hand, Wavell ordered O'Connor to keep on towards Tobruk, seizing this town with its water-purification plant and superb natural harbor, and drive the Italians back.

But now Churchill was intervening, demanding that Wavell withdraw three divisions and an armored brigade to Greece. Such a move would halt O'Connor in his tracks. While the leaders bickered, O'Connor rolled on.

Tobruk, a fortress town that would become legend, was held by 25,000 men, including Gen. della Mura's 61st Sirte Division, 45 light and 20 medium tanks, 200 guns, and the usual antitank ditches, two forts, Solaro and Pilastrino, and strongpoints. There was also the Italian cruiser San Giorgio, which had run aground after being bombed by the RAF, but which still had working guns. Twice as much ground and half as many men as at Bardia. But the Italians had no illusions about this defense.

The Australians advanced, short of water. 10th Corps was running out of vehicles due to the difficult terrain and dust storms. Trucks were being cannibalized. Tanks had thrown their treads. The Australian Divisional Cavalry had been forced to re-equip with captured and slow- moving Italian M-13s, all painted with the Aussies' leaping kangaroo symbol. Australian troops replaced their boots with captured Italian gear. The advance was slowed by fleas, lice, and Italian booby traps.

O'Connor and Mackay planned to hit Tobruk from the town's southeast corner, relying on the 16th Brigade to punch a hole, the 17th Brigade to follow up, and the 19th Brigade to exploit. Australian gunners prepared their bombardment thoroughly, to make up for the shortage of tanks -- there were only 18 to support the attack.

The assault went in on 21 January, delayed three days by dust storms. At Bardia, the Aussies were weighted down with equipment. At Tobruk they only wore jerkins, and carried weapons and ammunition.

The Italians fought back, relying on barbed wire and booby traps to augment their machine guns. Sgt. F. J. Hoddinott of Queensland hurled grenades to overcome Post S5. After half an hour, it fell. Post 62 fought back under tank and artillery shelling until Lt. F. D. Clark of Adelaide poured a mixture of crude oil and kerosene through the post's windows to silence it. 11 Italians died and 35 surrendered.

The expanding Australian drive became a torrent, as troops fanned out, losing contact with each other. Officers had to send dispatch riders out on captured motorcycles through the dust. Italian defenses collapsed under accurate Australian artillery fire. Again came heavy surrenders -- one company captured 300 men. Another hauled in 1,000 PoWs, including a general.

By mid-day, 19th Brigade's 2/8 Battalion was moving on Fort Pilastrino, the 61st Division's headquarters. The 2/8 came under fire from dug-in Italian tanks, so the Australians charged with bayonet and grenade, destroying the first tank. The rest surrendered. Next, 2/8 captured some mobile tanks, then some machine-gun positions.

The Italians counterattacked with nine tanks and hundreds of infantrymen. Private O. Z. Neall knocked out three Italian tanks with his Boyes anti-tank rifle, a feat that astounded everyone -- the Boyes rifle was noted for its uselessness. But the Italians continued to advance until two British Matildas rumbled up. At that point, the Italians ran, Australian infantrymen charging after them.

Fort Pilastrino fumed out to be simply a collection of barrack buildings surrounded by a wall, and Australian infantry took it quickly.

The 2/4 and 2/ll Battalions were also attacking, supported by British and Australian artillery. Their first objective was Fort Solaro, which housed the Tobruk garrison's headquarters. After a battle with Italian tanks on Tobruk's airfield, the Australians also found Solaro, which was just a few army buildings, unworthy of the title "Fort." Capt. H.S. Conkey saw some Italians driving away in trucks, and he and his pals hopped on some Italian motorcycles to capture the enemy. He scooped up 600 PoWs, but not Tobruk's top defenders; they had already fled.

The Australians continued to fight their way through sangars and wadis with tommy guns, and stumbled into some tunnels, which were obviously an enemy headquarters. Soon enough, an Italian officer came out, telling Lt. J. S. Copland of the 2/4 battalion he would surrender only to an officer.

"I'm an officer," Copland said, and Gen. Petassi Manella, commander of the 22nd Corps and the Tobruk garrison, looking dignified, quiet, and tired, handed over his pistol to Copland, in tears. Along with Manella, Copland bagged his chief of staff and 1,600 PoWs.

Manella was driven to 19th Brigade HQ and requested to surrender all of Tobruk. Manella told his captors his troops had orders from Mussolini to fight to a finish.

2/3 Battalion relied on heavy fire to make up for its lack of strength (a dozen men in one platoon) to intimidate the Italians. Soon Capt. J. N. Abbot's company was finding hundreds of Italian soldiers approaching, waving white rags.

By the end of the 21st, the Australians knew they had won. Most Italian guns were silent, Tobruk harbor was covered with black smoke, as the enemy was destroying ammunition and fuel. Behind Australian lines some 8,000 PoWs were trying to keep warm by lighting fires.

During the night, Italian SM.79s flew in to bomb the Australians, saw the fires lit by the PoWs, and bombed them. Italian bombs killed hundreds of their own men.

Next day, the 22nd, Mackay ordered the coup de grace. The Australians advanced on a wide front. Gen. della Mura of the 61st Division was bagged early and refused to surrender to the junior officer who caught him. No matter, thousands of della Mura's men were shuffling in to give up, anyway. At 9:30, Capt. I. R. Savige took the surrender of a local commander, who was persuaded to phone other Italian positions and order them to give up, too.

Lt. Col. K. W. Eather rode a Bren gun carrier over the edge of depression, saw a line of white flags, and found 3,000 Italians drawn up in parade formation with the officers in front, holding their luggage. The officers were shaven and wore well-tended uniforms and polished boots. Eather took the officers' pistols -- the other ranks had already thrown away their Mannlicher-Carcanos -- and thumbed them back.

Now the Australians were at the last escarpment before town. Lt. E. C. Hennessy of divisional cavalry rolled into Tobruk in a Bren carrier. He hit a barrier consisting of an iron girder supported by sandbags. Sgt. G. M. Mills hopped out with his crew to remove it and two Italians ran out to help. Then Hennessy and his team drove into the port.

Tobruk Falls

As they clattered down a street a neat Italian officer came forward to lead Hennessy to naval headquarters where Adm. Massmiliano Vietina was waiting to surrender. Hennessy sat the officer on the front of his carrier as "a guarantee of good faith" and they rattled through town to a large building. There stood Vietina ready to offer his sword.

Hennessy declined it, and sent a carrier back to fetch Brig. Robertson, who came quickly, along with a brace of Australian and British war correspondents.

The ritual was perfunctory. Vietina and his 1,500 men wished to surrender. All the booby traps and mines in town had been "sprung" and so were the ammo dumps and confidential papers. After the ceremony, Robertson and his men fired off Very flares to signify that Tobruk had fallen. An Australian soldier lowered the green and red flag of Italy and replaced it with a Digger's hat. Tobruk had fallen.

Hordes of defeated Italians trooped up from bunkers and shelters to surrender, while Australian troops fanned out to take control. About 25,000 PoWs had been taken, along with 208 guns, 23 tanks, 200 vehicles, the water distilleries, the port, and enough tinned food to keep the Italians going for two months. Australian casualties were 49 killed and 306 wounded.

16th Brigade soon found that victory was melancholy, as they had the near-impossible task of caring for thousands of PoWs, amid dust storms. The Australians themselves were short on water and supplies. It took 2/7 Battalion seven hours to feed all its captives. 2/2 Battalion kept its PoWs occupied by having them sing.

Only five of the 12 Italian divisions in Cyrenaica were left, and nearly half of these 250,000 men dead or captured.

O'Connor's new target was Dema, where "Electric Whiskers" Bergonzoli was organizing his 20th Corps. This force consisted of 60th Sabratha Division, 17th Pavia Division, and 27th Brescia Division, reinforced by Group Babini, a 70-tank armored brigade.

While the Australians sorted out Tobruk, 7th Ammoured was on the move. Wavell approved the advance to continue to Mechili and Dema, 11th Hussars leading the way. They ran into 50 M13s on the track and in the battle, destroyed nine for the loss of seven British. Clearly the Italians weren't done yet.

But Graziani was in despair; the Ariete Ammored Division hadn't arrived from Italy, and he frantically wired Rome that he faced 17 British divisions. "I had a vision of the future," he wrote,"I saw that it was not possible to avoid the fatality of the future!"

The two British divisions Graziani actually faced rumbled on through abandoned Italian colonial homesteads being torn up by looting Arabs. O'Connor planned to grab the Mechili crossroads by coup de main. Errors ensued. First, 4 Armoured Brigade got lost in the unmapped terrain -- O'Connor's men had literally driven off the edge of their maps -- but Babini Brigade's tanks didn't attack, missing a chance to chew up the 4th.

O'Connor rewrote his plan. 6th Australian would hit Dema and Bergonzoli's 21st Corps on the coast, while 7th Ammoured would put Babini Brigade at Mechili in a neat pincer, cutting the Italian armor inland from the coastal infantry.

As usual, the Italians reacted slowly, hampered by a byzantine chain of command and a lack of radios. But Babini fought hard on the 23rd at Mechili, ripping up the 11th Hussars light tanks and knocking the 2nd Royal Tank Regiment off balance. In a desert tank battle that looked like battleships maneuvering on the high seas, 2nd RTR counterattacked, caught the Italians skylined on a ridge, and picked them all off.

Even so, Graziani was pleased; his men were fighting back. He ordered 10th Army's commander, Tellera, to order Bergonzoli, to in turn order Babini, to attack the British flank. Tellera wavered, reporting that Babini had seen 150 British tanks (he was wrong), and Graziani lost his nerve, and ordered his armor to withdraw.

"If I had an armored unit, I could maneuver around enemy lines," he wired Mussolini. Graziani had an armored unit. He just didn't use it. "I am more or less in the position of a captain in command of his ship which is on the point of sinking, because errors are present on all sides," he whined.

At Derna

Meanwhile, the Australians took their whacks at Derna. 19 Brigade slugged it out with enemy artillery and machine guns for control of Dema's airstrip at Siret el Chreiba. The Aussies took on an "uncommonly determined" Italian rearguard. Little progress was made.

7th Armoured was stalled, too, mostly because its vehicles and men were exhausted from six weeks' campaigning and a stretched supply line. O'Connor doubted he would take Benghazi before German reinforcements arrived.

Bergonzoli's defense of Derna was determined and effficient. He placed his guns well, and his Bersaglieri troops fought hard. Italian supplies were plentiful, while 6th Australian's guns were down to 10 rounds a day. But the British pressure was too much. Bergonzoli asked Tellera to ask Graziani for more tanks.

Graziani received this flimsy with another signal from Mussolini on 27 January: "I want you to know, dear Marshal, that we are eating out our liver, night and day, to send you the necessaries for this arduous battle." The message promised more aircraft, the Ariete Armored Division, and more delays.

Graziani ordered his field commanders to "disengage speedily" from Derna. The Italians, after a burst of gunfire, set their ammo dumps ablaze, and retreated. Next morning, local Arabs told the bafffled Aussies that the Italians were gone. 6th Australian charged into an empty town of modern box-like houses on the coast, with gardens full of flowers and fresh vegetables -- the first the Australians had seen in a month. Libyans and Australians proceeded to loot the place.

When McKay himself drove into town, he found the few roads clogged with supply vehicles and Australian soldiers driving captured Fiats and trucks. The general fired off a blistering memo to his senior officers to get the Military Police in town to restore order and traffic control, then spent the last day of lanuary playing traffic cop at an intersection.

Bergonzoli had fled again, and the British couldn't pursue to Benghazi; 6th Australian lacked transport, and 7th Armoured's tanks had practically all thrown their treads. More importantly, 6th Australian found itself responsible for protecting nearly 90,000 Italian civilians who been brought to Libya to colonize the place.

Still, the Aussies kept moving. One battalion marched 70 miles in three days, slowed mostly by booby traps. Graziani, whose Cyrene bunker was now under RAF attack, fled to Tripoli, leaving Tellera and Bergonzoli in command.

O'Connor, racked by fatigue and stomach trouble, was facing the certainty of his offensive stalling out in front of Benghazi. The Germans would reinforce through the port, and reverse Axis fortunes. O'Connor cast round for another scent.

O'Connor's solution was breathtaking in its genius...his Australian infantry would continue to drive steadily on Benghazi. Meanwhile, the overworked and exhausted 7th Armoured would cut across the desert tracks south of Benghazi to a hamlet called Beda Fomm, and cut off the retreating Italian 10th Army in a classic ambush. If the move worked, the 10th Army would collapse. If it failed, 7th Armoured would have only three days of supplies to hold out in the desert. After that, it would be doomed.

Risky and Dangerous

It was the kind of move that Hollywood would later attribute to American generals, and not consider possible by British officers and troops -- risky and dangerous, but with great potential if it worked.

O'Connor sent his chief of staff, Brig. Eric Dorman-Smith, back to Cairo with the plan on 31 January. Wavell heard Dorman-Smith's report and saiid, "Tell Dick he can go on, and wish him luck from me. He has done well."

Wavell backed his quote with a supply convoy that sailed to Tobruk, whose vehicles were sent to Mechili to re-supply 7th Armoured's panniers. It was just possible for the division to move out with full vehicles 11th Hussars had already started; the rest of the division would move on the 5th, with barely 45 heavy tanks, 80 light tanks, two days' supplies of food and water, and two refills of ammunition. Hardly enough against Tellera's four divisions.

"It is likely that tonight the enemy mechanical columns will move on Msus Sceleidima, marching even with lights on," Tellera's radiointercept teams noted. The Italians were right, but Tellera could do lime to block the British advance over tracks through villages named Msus, Sceleidema, and Antelat.

Can't Do It

In any case, the Italians weren't worried. '`They can't do it," one Italian officer said. "And even if they do do it we still have two days to spare." The Italians confined countermeasures to light aerial minelaying, and alerting their detachments in the area.

The British weren't sure the move was possible, either. British war correspondent Alexander Clifford wrote,"For mile aRer mile they juddered over great slabs of sharp, uneven rock. Then they crossed belts of sofl, fine sand, which engulfed vehicles up to their axles. Sandstorms blew up, and the trucks had to keep almost touching if they were not to lose one another.

Whole convoys lurched off into the gloom and only re-established contact hours later. It was freezing cold, and the latter half of the division had to contend with fierce, icy showers. All kit had been cut to the bone, and there were no extra blankets or greatcoats, and scarcely more than a glass of water per man per day."

A tank commander in 1/RTR wrote, "The march was a complete nightmare and I remember little about it because most of the time I was too tired and bruised by my bucking tank."

It was bitterly cold, and, for much of the way, it was either raining or blowing a sandstorm...by day the squadron was deployed on a very wide front with the task of finding the easiest passage through the rough and rocky countryside. If a tank broke down, and many did, the crew reported its position and they stayed with it until the Divisional recovery teams towed it back to Tobruk."

One light tank, lost in this way, spent three weeks without recovery, eking out three days rations, until their word HELP, etched in the sand, caught the eye of a passing RAF aircraft.

With the indefatigable 11th Hussars leading, Msus was reached and cleared of a small Italian detachment on 4 February. While the British advanced, word came down that the Italians were retreating into Tripolitania. Maj. Gen. O'Moore Creagh, commanding 7th Armoured, was ordered to speed his offensive.

Faster

Creagh organized his fastest vehicles into an ad hoc team under Lt. Col. John Combe, called Combeforce, and sent them on ahead. This force consisted entirely of 11th Hussars, 2nd Rifle Brigade, C Battery ofthe 4th Royal Horse Artillery, and 106th Battery RHA with is truck mounted 37mm anti-tank guns. Most vehicles were wheeled. Combeforce had 2,000 men and no tanks. They would pin down the Italians until the rest of the division arrived.

Combe looked at his maps, and chose to move via Antelat across the tracks and cut the Italian retreat off et a spot called Beda Fomm, which consisted of a few huts and a mosque.

Just before dawn on the 5th, Combeforce jolted across the terrain, armored cars leading, artillery behind, across uncharted ground, relying on compass bearings to stay on track. At noon the 11th Hussars reached the coast to find no Italian vehicles. That meant the Italians had yet to arrive.

Relieved, Combe settled his infantry into a system of shallow ridges through which passed the road from north to south. The Bren carriers were left behind, out of gas. Behind the infantry the artillery and armored cars dug in.

At 2:30 p.m., sharp-eyed British soldiers saw a cloud of dust heading towards them. It was the retreating Italian 10th Army. Combe and O'Connor had won the race -- by two hours.

The Italians were weary men of the 10th Bersaglieri, escorting a motley collection of air force ground-crew, colonial administrators, gunners without guns, and frightened civilians. As they made the turn in the road, the vehicles came under machine gun fire, and hit land mines.

10th Bersaglieri stopped its retreat to take on the 1st King's Royal Rifle Corps, but came under 25-lbr. artillery fire. The Italians, realizing their retreat was blocked, attacked with ferocity, but made no headway against British fire-discipline.

At dawn on the 5th, the 4th Armoured Brigade moved towards Beda Fomm behind Combeforce, clearing the 40-mile journey by 4 p.m. They reached the scene north of the British ambush line to find an endless line of Italian vehicles strung along the Coast Road, waiting to retreat. 4th Armoured was down to its last drops of fuel, but it charged into the Italian mass with gusto.

The Italians themselves were shocked, and in many cases, unable to respond, as the columns were mostly poorly-armed support troops. Panicked Italian drivers turned their vehicles into sand dunes and became bogged down. Those that didn't flee received 40mm ordnance, which set fuel trucks alight, providing illumination for Combe's artillerymen, who added their 25-lbr. shells to the din.

British infantry dismounted to take more than 800 PoWs and salvage captured vehicles. Some of them were fuel trucks, and British tank crewmen refueled their empty vehicles on the spot.

Bizarre

The battle took on bizarre tones. One Hussar sergeant kept his PoWs in check with his Very pistol until he was politely handed a Breda automatic by an Italian who spoke English with an American accent and had spent 11 years in the United States.

The British fanned across the area. One British squadron shot its way along the 10 miles of fighting, replenished its shells and fuel, and then fought all the way back. When Italian tanks tried to counterattack, Royal Engineers moved forward, laid a minefield in front of the enemy, and the attack was halted.

2nd RTR rolled north and dismembered a flak battery, sweeping up guns, men and vehicles by the light of burning trucks. The Italians were in a shambles.

Problem was, so were the British. They were down to their last fuel, despite some captures. Tankers were siphoning fuel from their gunner vehicles. Creagh ordered his division to dig in for the night, refuel, and move 5,000 PoWs out.

While the British ate gummy bully beef, two Italian tanks came rumbling up. A 2nd RTR trooper knocked in turn on the Italian hatch tops, and at pistol point, persuaded the Italians to surrender.

During the night, the British supply vehicles came up, and 7th Armoured refilled its panniers. The situation was serious for both sides: The Italians were cut off, and the British were practically out of supply.

Next Day

The next day, 6 February, dawned wet and windy. Both sides were exhausted, having been unable to rest during the night. Tellera and Bergonzoli were determined to break through to safety. To the east of Benghazi, the Australians advanced. Barce's Italian ammunition dump went up in a dramatic ball of smoke, and Babini Group faced the whole 6th Australian. At Sceledeima, Italian troops fought hard against advancing Australians.

Tasked with the breakout at Beda Fomm, Bergonzoli knew his 21st Corps was on its own. Lacking reconaissance and adequate information, he voted for a short hook east through the desert and outflank the British defenders, relying on superior numbers.

The Italians moved out at 8:30 a.m., without artillery, targeting a small rise in the road just west of the mosque, logically called the Pimple.

Meanwhilc, the British, under Brig. J. A. L. Caunter, prepared for the attack. 4th Armoured Brigade was nearly at the end of its tanks division's reserve was only 10 cruiser tanks. Caunter had plenty of worries: cold, wind, rain, sandstorms, and the fact that he was far beyond the range of RAF support.

At dawn, patrols told Caunter the Italian column, stretching for miles, was moving south. Caunter's men stood to. 2nd RTR, with 19 tanks at the edge of a slope, faced 60 Italian machines at the Pimple.

But as the Italians attacked, the British got in the all-important first shot, their guns ripping through the Italian armor, turning M13s into burning coffins, wrecking eight. Before the stunned Italians could return fire, the British had withdrawn down the slope, to repeat the example, destroying seven more tanks with no loss. The Italians opened up with artillery and committed their reserves, as did the British.

The Italian numerical advantage was no help. Most Italian vehicles had no radios. The British instituted a drill movement right out of Salisbury Plain training exercises. With the snap order,"Hello all stations. Tanks left and attack the Pimple," the British counterattacked.

The Italians, lacking the effciency of radio, stolidly moved to their predetermined objectives, and waited for orders. The Italians fought with great determination but in total disarray.

A Squadron of 2nd RTR soon scooped up 250 PoWs. British artillery expended nearly all it ammunition to break up attacking Italian infantry columns.

At 10 am., The Italian defenders at Sceledeima were told to pull out and get to the Pimple. They raced down the road and into the 7th Hussars.

Even so, the British were in trouble. The Italians were streaming down endlessly; 60 tanks had been knocked out, but more were coming...and 2nd RTR was out of ammunition...4th Brigade needed more help. Where was 1st RTR?

By 11:25 a.m., 2nd RTR was down to 13 cruiser tanks. At noon it only had 10. 7th Hussars was in worse shape -- it had only one cruiser tank left.

The Italians, sensing victory, kept charging, firing artillery over open sights at pointblank range.

The crisis hit at 3 p.m. 7 Hussars found the tail of the Italian column and attacked it. 3rd Hussars battled Italian tanks. 2nd RTR, driven off the Pimple, tried to break round. Now British radio communications had broken down. At this point, it seemed the British might crack.

But the 1/RTR finally arrived, and rumbled towards the sound of the guns, driving the Italian tanks northwest. Bergonzoli was halted. 2nd RTR had destroyed 51 M13s for a loss of 3 tanks and seen men. Other outfits destroyed 33 tanks. 10,000 Italians had surrendered.

Poring over his maps, Bergonzoli decided to try a night attack on the sand dunes west of the Coast Road. No luck. British artillery closed that route.

Both sides, exhausted, flopped down in the gathering desert dusk.

To the north, the Australians enjoyed yet another success, as 6th Division finally entered Benghazi. Lt. W. M. Knox of 2/8 Battalion drove into town to find the population of 50,00 Greeks, Jews, Italians, and Arabs, waving and cheering the Australian column. Knox drove to town hall where the Italian civic rulers awaited him. Knox handed the Italians orders that charged them with maintaining law and order until the rest of the division could arrive. The mayor delivered a speech of welcome, calling the Australians"our brave allies," which baffled the Diggers.

Next moming, at Beda Fomm, Bergonzoli mustered his last 30 tanks for one final dawn assault. With 6th Australian breathing down his neck, Bergonzoli was out of time, space, and ideas.

The attack was based on the courage of desperation, and it hit the 106th RHA's portee-mounted guns. The Italians pressed through, having knocked out all but one of the anti-tank guns. That gun was manned by the battery commander, his batman, and a cook. They destroyed the last Italian tank.

British infantry battered the attacking Italian riflemen, leaving the M13s 20 yards from their objective, but completely unsupported. Tellera himself led a bayonet charge and was mortally wounded. 10th Army was defeated. At 9 a.m., white flags went up over the Italian lines.

O'Connor himself, who had directed the British battle, drove to a farmhouse near Soluch where half a dozen Italian generals in snappy uniforms and polished boots were held prisoner, the elusive "Electric Whiskers" Bergonzoli among them. O'Connor, like Grant at Appomattox, was casually dressed -- corduroy trousers, leather sleeveless jerkin, tartan scarf, and sagging cap.

"I am sorry you are so uncomfortable," said O'Connor."We haven't had much time to make proper arrangements."

"Thank you very much," said Gen. Cona, for his defeated colleagues. "We realize you came here in a great hurry."

O'Connor's aide Dorman-Smith fired off a message to Wavell, "Fox killed in the open."

Around O'Connor was the wreckage of the Italian 10th Army. He surveyed a scene clogged with more than 25,000 PoWs, more than 100 tanks (some of which were serviceable), 216 guns, and 1,500 wheeled vehicles. Under the blue African sky, small gazelles bounded through the scrub.

"I have seldom seen such a scene of wreckage and confusion as existed on the main Benghazi road," wrote O'Connor. "Broken up and overturned lorries; in some places guns, lorries and tanks in hopeless confusion. Elsewhere guns in action and broken down M13s. All over the countryside and everywhere masses of prisoners. Most of the enemy tanks had dead men inside them...Gen. Tellera, the Army Commander, was in one lying seriously wounded. He died later in the day."

The mess was too great for even the Arabs to loot. The wreckage of 10th Army lay strewn around Beda Fomm for years.

O'Connor wasted no time. Within hours, 11th Hussars, on captured fuel, was speeding along the road to El Agheila, where they stopped, ending the "5-day raid" two months after it began.

British Triumph

The campaign was over. It was a complete British triumph, one that would be studied for decades in staffcolleges. For a loss of 500 dead, 55 missing, and 1,373 wounded, 30,000 British troops had advanced 500 miles in two months, destroyed an army of 10 divisions (including Mussolini's vaunted Blackshirts), and taken 130,000 PoWs, 400 tanks, and 1,290 guns. The reputation of Mussolini's Fascist Italy had been torn to shreds.

So had Graziani's. He was summarily fired, and replaced by his subordinate, Gen. Gariboldi. Gariboldi dug in to await the inevitable British drive on Tripoli.

It never came. Wavell's eyes were on Greece. O'Connor sent Dorman-Smith to Cairo for permission to advance, but was too late. "I am beginning my spring campaign, Eric," Wavell told DormanSmith, while looking at a map of the Balkans.

7th Armoured returned to Egypt to re-fit. 6d~ Australian and 2nd New Zealand Division shipped out to Greece. The new 2nd Armoured Division was to man the line at El Agheila. The British had given up the initiative in the Libyan desert.

This decision, made by Churchill, and backed completely by Wavell, to drain off scarce British strength to hold Greece, was one of the worst of the war. The Axis had lost the Italian 10th Army, and Mussolini what was left of his reputation, but Hitler was about to rewrite the play on Libya's barren stage.

Rommel Arrives

"Dearest Lu. Landed at Staaken 12:45. First to C-in-C of the Army, who appointed me to my new job, and then to the Fuhrer. Things are moving fast. My kit is coming here. I can only take barest necessities with me. Perhaps I'll be able to get the rest out soon. I need not tell you how my head is swimming with all the many things there are to be done. It'll be months before anything materializes. So 'our leave' was cut short again. Don't be sad, it had to be. The new job is very big and important..."

So wrote Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel of the Germany Army to his wife Lucie on 6 February, the day of the battle of Beda Fomm. The "new job" was to take over an outfit the Germans were shipping to Libya, the Afrika Korps. The shape of the desert war was about to change completely, and a legend was about to be born.

Desert Dawn: Europa as History: 1940-1941

Back to Europa Number 55 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com