The need for time grading comes partly from air operations. The air-unit sizes and the number of air phases used in Europa are both out of sync with naval combat. Where a Ju88 Gruppen of 40-50 aircraft might fly 10 or even 20 sorties per plane against a Soviet defensive line during a 15-day turn, convoys heading for Murmansk give the Ju88s no more than 2 or 3 days in which to do their worst. In bad weather, this might only amount to one successful sortie per plane.

Aside from the puzzle of exactly how to rate the Ju88 against admittedly vulnerable merchant ships (and the complementary puzzle of escort carriers), there is the big problem of accounting for what everyone does for the other 14 days. In naval warfare, space is larger; time is shorter. The solution (sorry, the elegant kludge) is not just a bigger hex, but a time-graded sea zone.

I'll make this point another way. The 16-mile hex is too small for a 15-day naval turn, and the 15-day turn is too long for aeronaval operations. Attempting to meet the problem using hex-by-hex movement of ships and a similarly accurate measurement of time, leads either to:

- a) simultaneous plotting (as in tactical naval

games);

b) alternating, interruptible subturns of irregular length (as in most operational naval games today, e.g. Pacific War);

or worst of all,

c) a numbing cascade of sub-phases (i.e., the total

of 14 identical phases within each pair of player turns in

Supermarina).

We need to make spaces larger and time smaller. The minimum we must do is make naval movement more flexible than the best possible land movement. Since combat/motorized units get two moves in a turn, naval units should at the very least get three. This minimum turns out to be a maximum as well; every step of movement above three adds complexity we may not need. Now assuming as a rule of thumb that Supermarina is right in principle-that the time- space ratio for ships should be 14 times that for land units- this means that spaces should be at least 14/3 or about 5 times larger. That's a 5-hex sea zone.

So far I've argued for zones, and for time-graded zones; but why zones of fixed radius? Because a fixed radius allows a time-graded zone to work properly. In every Europa series game featuring sea zones thus far, the region sizes have varied wildly.

- The sea areas in Their Finest Hour (TFH) are arbitrary and ungraded (ranging from about 2 hexes across to more than 15), because time and motion considerations are restricted to staging for a single invasion scenario. Imagine getting just one 2-hex, 1-zone move with your destroyer flotilla in a 15-day turn!

- There are varying numbers of shipping staging areas from the Baltic to the Arctic Ocean in FITE/SE and Narvik. The counters representing the Soviet fleets have unlimited movement in their limited domains, but no actual naval opposition, so there is no need for precision.

- Finally, there are 2 broad zones, the Adriatic and the Aegean, in Baltic Front. Since there are again no opposing naval units, they serve mainly as a fudge factor to prevent ahistorical use of sea transport.

So, here is the point of time-graded, fixed-radius sea zones. Suppose you are the Axis player facing an invasion of the Italian mainland in September 1943. Allied task forces sail from Sicily, from Tunisia, and, in a surprise move, direct from Britain. Elements from all three wind up in the sea zone containing the port of Naples. You frantically assault this mass of shipping with your SM.82 torpedo bombers, your U-boats, your Italian MTBs, and everything but the kitchen sink.

Now what?

Task force A, from Sicily, carries assault troops; because it is mostly smaller snips, it took a lot of its range just getting to the beaches, and must offload and go home. Task force B, from Britain, carries the supplies and follow-on waves the Allies will need for exploitation and for next turn. Meanwhile task force C, from Tunisia, contains most of the bombardment ships.

With a time track, this is all clear, because we can measure the actual period of danger for each ship to within a day or two. After a quick swipe at the small craft, you would settle down to nibbling at the masses of follow-on shipping, while the Allied player busily unloads and then hurries his assault ships home to collect another wave of troops.

Without a time track, you've either got to use umpteen markers, or remember everything, or play a dozen identical phases, or just not give a damn and treat them all alike--something either the bombardment force or the landing-craft commander might not like.

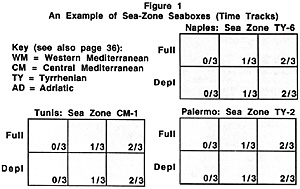

As shown in Figure 1, each sea zone contains

a seabox consisting of two rows of three boxes. The top row

is for shipping that is fully replenished; all the ships involved

will start by using this row. The small craft use the column

marked "0/3", which means that they spend no time at all on

station; they are constantly in movement. The follow-on

shipping uses column "1/3," which means that it spends

roughly one-third of the available time on station, waiting to

deliver cargo.

As shown in Figure 1, each sea zone contains

a seabox consisting of two rows of three boxes. The top row

is for shipping that is fully replenished; all the ships involved

will start by using this row. The small craft use the column

marked "0/3", which means that they spend no time at all on

station; they are constantly in movement. The follow-on

shipping uses column "1/3," which means that it spends

roughly one-third of the available time on station, waiting to

deliver cargo.

The bombardment force uses column "2/3", which means that it spends the maximum possible amount of time offshore, delivering support. Once the bombardment force exhausts its ammunition, it must either return to port to reload, or shift to the "2/3" column in the second row, which is the depleted row.

The time track has two separate functions; to indicate how much time the ship is spending in this particular zone, and to indicate its supply status. This second function is as important than the first, because it allows easy accounting in multi-turn operations.

For example, in TFH ships and submarines armed with torpedoes are subject to ammunition depletion; this involves a lot of roster-checking and possibility for error. The seabox puts the status before you graphically. (Incidentally, AA ammunition was probably as crucial a problem as torpedo reloads: see Kenneth Macksey's Invasion, for example.)

However, there is more. This method of dividing the ship's time-on-station into thirds is based on individual movement steps, not game-turns. We have said that we shall have three movement steps: they are Movement, Exploitation, and Reaction.

The first naval movement step takes place as part of the normal movement phase; then there is a second naval step that takes place during exploitation phase. A player may also make a normal naval move during his opponent's movement phase, in a naval reaction step. Each of these three naval movement steps has a corresponding return to base step. This creates enough flexibility for naval forces to act as they did historically.

A battleship with escorts, having bombarded Genoa in the friendly combat phase and depleted itself, might put into Malta in the return to port phase, then appear off Greece in the friendly exploitation phase, where it would provide defensive fire support during the whole opposing player turn. It would get depleted in the opposing player's combat phase, and move into the depleted column. It would then return to base in Alexandria, and be resupplied and ready for operations again at the start of the following friendly turn.

This sort of multiturn trick is essential to naval operations; it is the chief reason why the Royal Navy could be everywhere at once. But if we need to use rosters or supply markers or similar stuff to keep track of it, the game won't get played. That's why the seabox is so crucial. There's no need to remember anything; where the ship counter sits tells the whole story.

The Case for Sea Zones The Europa Naval Rules Get a Refit

- Introduction

Part 1: Why Sea Zones Should Be Time-Graded (and Fixed-Radius)

Part 2: The 3-Naval-Phase Sequence of Play

Part 3: The 61-Hex Sea Zone

Conclusion

Back to Europa Number 25 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com