The Dominican Republic occupied the eastern two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola, and was peopled by the descendants of Spanish colonists and their slaves. The population, numbering more than 1,000,000, comprised an elite of white Dominicans and a mulatto majority, most of whom lived by subsistence farming. Yet the republic exported enough sugar, coffee and cacao to make the customs service attractive to corrupt office seekers.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Dominicans had been alternately occupied and governed by Spain, France and Haiti. Since gaining independence from the latter country in 1844, they had been ruled by caudillos, military strongmen. who depended on their own private armies.

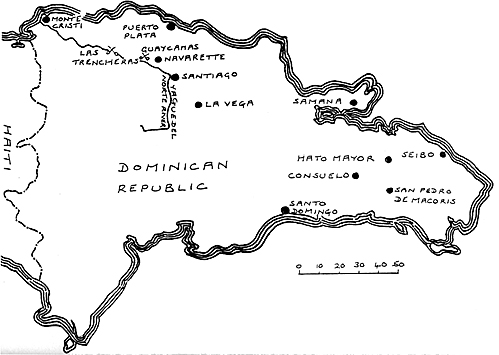

Topographically, the western half of the Dominican Republic was mountainous and under populated. The economic and political life of the country centred on two other regions. The northern region ran from the ports of Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata, through the Cibao Valley and its principal city, Santiago, to Samana Bay in the north-east, which was a centre of foreign investment in sugar, and suitable for use as a naval base. In this region was situated the republic's only sizeable railway, which ran from Puerto Plata to Samana Bay. The other populous region was the south-eastern coastal area around the capital of Santo Domingo. A coastal road linked the capital with the heavily populated farming provinces to the east, an area traditionally plagued by banditry.

The Dominican Republic's corrupt political class regarded government office as both a right and an economic necessity, and to keep these politicos in the style to which they were accustomed, the Government had accumulated massive foreign debts by the early part of the twentieth century. Indeed, as one historian has pointed out, "it had defaulted and refinanced with such dizzying romanticism and corruption that no one was sure just what it owed," though it appears that the sum was between $20,000,000 and $32,000,000. (Millett, 1980, 179) Among the creditors were a number of European banks and the American owned San Domingo Improvement Company. As much of the Government's income ended up in the pockets of the politicos, Dominican governments had difficulty in making debt repayments, a condition which made foreign intervention likely.

Another problem was the republic's persistent political instability. Dominican presidents, lacking a modern, dependable army or police force, were particularly vulnerable to coups or civil wars. The result was that only the most ruthless national leaders remained in office for long. One such was Ulíses Heureaux, president from the early 1880s to 1899, who, it is said, invited one of his opponents to dinner, and, after an excellent meal, declared "Have a cigar. It will be your last. I'm about to have you shot." (Quoted in Langley, 1985, 27)

American interest dated back to the early nineteenth century, but the United States Government took a more active interest after the war with Spain and the creation of the Panama Canal Zone. Initially, the Roosevelt administration (1901-08) was most concerned with the traditional tasks of protecting American lives and property. But when, in 1902, Britain, France and Germany collected debt repayments from Venezuela by force, American thinking became increasingly dominated by strategic concerns. It was feared that either

France or Germany might, under the guise of collecting debt repayments, take control of the Dominican Republic and establish a naval base at Samana Bay. Naval forces operating from there could control the Mona Passage into the Caribbean Sea and access to the Panama Canal.

Roosevelt Expediency

The Roosevelt administration decided that the most expedient way of preventing European intervention was through the creation of a system whereby the republic could repay its foreign debts. And so, at the request of the then Dominican president, General Carlos Morales, the State Department, between 1905 and 1907, worked out a set of agreements that gave the United States control of the Dominican customs service. Under American management, forty-five per cent of the receipts would be handed over to Dominican officials, and the remainder transferred to New York banks for disbursement to the republic's creditors. This agreement pacified foreign creditors and their governments, but it did nothing to curb the Dominicans propensity for political violence.

And so, after the assassination of another president in 1911, the republic again sank into chaos as the políticos fought one another to decide upon a successor. Sporadic fighting dragged on into 1913, with neither faction able to gain a decisive victory. American naval officers and legation officials negotiated truces and urged compromise, and the State Department considered defending the customs houses with Marines.

Into this quagmire stepped the newly elected American president, Woodrow Wilson. An American historian has summed up the policies of the Roosevelt and Taft administrations with regard to the Dominican Republic thus:

"We (the USA) would collect the customs, set aside 55 per cent for satisfying foreign claimants, and give the politicians of Santo Domingo the remainder. We would protect the customs houses from the perils of insurrection. After that, if their political house was in disorder - and it usually was - it was their house."(Langley, 1985, 121)

Wilson, influenced by his belief that he could "teach the South American republics to elect good men," went much further. Under his plan, the United States would supervise both the election of a new Dominican president and the re-ordering of the republic's finances. The supervised elections led, in late 1914, to the election of Juan Isidro Jiménez as president. Old and ailing, Jiménez was inclined to go along with American financial supervision of Dominican affairs, but the National Assembly opposed him, and, in 1916, the anti-American Minister of War, General Desiderio Arias, went into rebellion and seized the capital. Jiménez at first accepted an offer of American military assistance, but then changed his mind and resigned on 7 May 1916.

US Intervention

The Americans then decided to go in without an invitation. On 12 May, four US warships, under Rear-Admiral William Banks Caperton, arrived off Santo Domingo. And, by daybreak on the 13th, they had landed 600 bluejackets and Marines. Caperton then presented Arias with an ultimatum - surrender, or United States forces would occupy the capital and forcibly disarm the rebels. That night, with about 300 followers, Arias stole out of Santo Domingo and headed for his regional base at Santiago, in the Cibao Valley. On the morning of the 15th, in the face of some rooftop sniping from the Dominicans, American forces occupied the capital.

Because the Dominican Republic now had no constitutional government, and Caperton and the American Minister, William W. Russel, were afraid that the Dominican Congress would select Arias if pressed to form one, the State Department asked the Navy to take full control of the country while it negotiated to find a compliant new regime.

To make this policy viable, United States forces would have to disperse Arias's army in the north. This they began to do on 1 June, when the gunboat USS Sacramento appeared off Puerto Plata, which was held by about 500 Arias irregulars. The governor, an Arias supporter, refused to order the surrender of the fort guarding the harbour. The captain of the Sacramento fired a warning shot, then ordered a ten minute bombardment which reduced the fort to rubble. 130 Marines and bluejackets then landed and took possession of the town.

On the same day, the gunboat USS Panther appeared off Monte Cristi. Thanks to the help of the German consul, Herr Lampke, who seems to have had more influence than the local Arias chieftain, Miguelito, a landing party took possession of the town without incident. But Miguelito's small force camped outside the town, fired into it every night, and cut off the food supply to the residents. Captain Frederick N. Wise, USMC, took a detachment with a machine gun, and, in a sharp encounter a few miles from the town, put the rebels to flight.

Caperton's next move was to occupy Santiago, Moca and La Vega. The plan was for Colonel Joseph H. Pendleton's 4th Marine Regiment (about 850 men) to advance from Monte Cristi, through the valley carved out by the Yague del Norte River between the central mountain range and the coastal chain. A smaller force, consisting of two companies and the ships guards of the Rhode Island and New Jersey, was to move inland from Puerto Plata, as far as possible on the railway, and then march on to Navarette, a small village about twelve miles west of Santiago, where the road from Monte Cristi and the railway from Puerto Plata converged. Here, the two columns would rendezvous for the final assault on Santiago.

At Las Trencheras ridge, on 27 June, the rebels made a stand. Pendleton's artillery pulverised their trenches as the Marines advanced, using the thick bush as cover. The rebels turned and fled, destroying every bridge behind them.

On 28 June, a rebel night attack was beaten off. Five days later, at Guaycamas, the Dominicans made another stand. Pendleton's artillerymen could not adequately position their pieces, so the Marine machine gunners hauled their Benet-Merciers to within 200 yards of the rebel lines, and, opening a deadly fire, forced the enemy to retreat. Next day, the 4th Regiment reached Navarette and joined up with the column from Puerto Plata. The latter had encountered opposition only once, at Alta Mira, where the track passed through 300 yards of tunnel. The column commander, Major Hiram Bearss, and sixty men had plunged through the tunnel, and the rebels had run off to Santiago.

As the columns approached Santiago, a delegation of citizens came out to meet them and explain that Arias intended to leave the city. They asked Pendleton to slow his advance to allow the General time to depart. Pendleton agreed, and occupied Santiago without firing a shot on 6 July.

Meanwhile, Russel and Caperton had been attempting to find a Dominican politician willing to work harmoniously with the United States. Since none existed, the State Department, after several months of impasse, asked Wilson to allow it to govern through an American military government. The President agreed, and, on 29 November 1916, Captain (later Rear-Admiral) Harry S. Knapp proclaimed himself military governor of the Dominican Republic. To enforce his authority, the new Governor had at his disposal 2nd

Marine Brigade, consisting of the 3rd and 4th Marine Regiments.

Bandits

Formal, organized resistance to the American occupation came to an end with the disbandment of Arias's army at Santiago in early July 1916. Yet, for the next six years, hardly a month went by without an armed clash between the Marines and hostile forces, whom the Americans lumped together under the label bandits. These bandits were not a homogeneous group: some were professional highwaymen, or gavilleros; others were politically opposed to the American intervention, and had taken up arms against it; still others were unemployed labourers driven by poverty; and some were peasants who had been recruited into the bandit gangs by duress.

Operating in bands that rarely exceeded 200 men and usually numbered less than 50, the bandits robbed and terrorised rural communities, extorted money, ammunition and supplies from the large sugar estates, and sometimes attacked small Marine units. At all times, their presence in the countryside was a threat to the security of the population and a challenge to the authority of the military government. The gangs usually coalesced around a leader notable for his dynamic personality, ferocity or physical strength. Many of these men were little more than gangsters, but a few had the character of local political chiefs or warlords. In this category could be placed the brutal Vicentico Evangelista, who, for a while, could muster nearly 300 armed men, and threatened to become the de facto ruler of eastern Santo Domingo; and Diaz Olivorio, who attracted a large following by preaching a religion of his own devising. Whether to reinforce their local standing or assert their territorial control, these major leaders were responsible for most of the bandit attacks on American Marines and civilians. The bandits armament varied from gang to gang. While some carried little more than machetes, a few pistols and black powder rifles, others possessed modern small arms, including an occasional US made Krag-Jorgensen or Springfield rifle.

Bandit activity was centred in the two eastern provinces of Seibo and Macoris, where the densely thicketed terrain favoured the operations of the gangs. Economic conditions in these provinces deteriorated in 1918, when World War I disrupted the country's export trade. In addition, a progressively larger proportion of the peasantry had been switching to work as seasonally employed cane-cutters on the sugar plantations, and had lost the ability and will to farm. Such men were obvious candidates for a bandit life.

In the eastern provinces, and to a lesser extent elsewhere, the bandits had at least the passive support of the country people. While they suffered at the hands of the gangs, many of the peasants and villagers resented the American occupation, and regarded the bandits, who occasionally talked as if their objective was not just loot, but the defeat of the occupation as patriotic resistance fighters. Consequently, Dominican civilians, whether out of hostility towards the Americans, or fear of bandit reprisals, would rarely provide the Marines with accurate or timely intelligence.

The Marines did, however, score an early success against Vicentico Evangelista. This ferocious partisan boasted that he would kill every American in the republic, and began by murdering two American civilians, engineers from an American-owned plantation, who were lashed to trees and hacked to death with machetes. Their bodies were then left dangling for wild boars to eat.

In March 1917, Evangelista attacked a Marine patrol at Cerrito, but was driven off. The Americans then decided to lure him into a trap. They hired a rival bandit chief, Fidel Ferrer, who knew the terrain and the enemy, to lead his gang against Vicentico. They also inserted a civilian agent, Antonio Draiby, himself a part-time outlaw, into Vicentico's band. Eventually, Draiby arranged a meeting between Vicentico and Marine First Sergeant William West, at which the bandit leader was (according to Dominican accounts) offered 10,000 pesos to bring his men out of the hills and surrender. This Vicentico did on 5 July 1917. The Marines then disarmed and released most of his nearly 200 men, many of whom had been impressed into the bandit ranks. Vicentico himself and forty-eight of his hard-core followers were held for trial on charges that included eleven murders and scores of rapes; but the bandit leader was killed while trying to escape before he had to face trial.

The capture of Vicentico cannot obscure the fact that, from 1917-1919, neither 2nd Marine Brigade, nor the newly formed, American officered native constabulary, the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, was able to react effectively to the bandit threat. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, many of 2nd Brigade's best officers left it for the battlefront in France. The result was that, particularly after mid-1918, Marine commanders in the Dominican Republic complained of a shortage of junior officers, and that the officers sent to them were often ill-prepared for their jobs. In late 1918, for example, one company commander found himself stationed in the hills of eastern Santo Domingo with only two lieutenants for 150 enlisted men. He soon had to relieve one of the lieutenants from field duty for misconduct and pressed a Navy medical officer into temporary troop command to replace him.

Another wartime officer who had to be relieved for misconduct was Captain Charles Merkel, a former ranker who became known as the "Tiger of Seibo." In his regular patrols of the province, Merkel habitually arrested ordinary country people - men, women and even children - for withholding information about the bandits. This seems to have been his method of carrying out the re-concentration policies of the Marine commander at Hata Mayor, Lieutenant Colonel George C. Thorpe, which called for the rounding up of people in the countryside. During these drives, Merkel seems, on more than one occasion, to have extracted information from prisoners by torture, and, in September 1918, after numerous charges of cruelty, he was arrested. While awaiting court martial he blew out his brains with a pistol, which the official record states he had secreted on his person. The unofficial version is that two Marine officers visited his cell and left the gun and one cartridge.

World War I also had an effect on the quality of 2nd Brigade's rank and file. This did not become apparent for a time, as most of the wartime volunteers who were drafted into the brigade were good material, though they were disappointed and disgruntled at having to serve in the Dominican Republic instead of fighting on the Western Front.

Draftee Marines

On 8 August 1918, however, voluntary recruiting for the Marine Corps was suspended by order of the Secretary of the Navy, and not resumed till 4 December 1918. In the interval, draftees were accepted for induction into the Marine Corps if they met Marine standards. Many of these men, who had been called for induction before 11 November 1918, were inducted after that date.

Late in 1918, these World War I draftees came flooding into the Corps, many of them less thoroughly trained than previous recruits. One detachment of these men in bandit territory, on their first night in camp, mistook the flare of lighted cigarettes for enemy rifle flashes.

They blazed away with their own weapons, and only their poor marksmanship prevented them from mowing down the battalion commander's escort.

The draftees presented 2nd Brigade with discipline problems, for many of them resented being kept in service after the Armistice. In early 1919, for example, temporary Captain (later Lieutenant General) Edward A. Craig, on joining a company, found his men very poorly trained and in a near mutinous state. Joining forces with two trustworthy NCOs, and, for a while, sleeping at night with a Browning automatic rifle under his bed, he worked them into a disciplined unit after a number of bad experiences.

During World War I, the Guardia Nacional suffered from the same officer problems as the Marine brigade, and, with a strength of 691 men by the end of 1917, it was neither large enough, nor well enough trained to be of much help in policing the interior of the country, especially in patrolling against bandits. The force's native officers and men, used to the corrupt and arbitrary methods of earlier Dominican constabularies, all too often used their official positions to settle grudges, and were too eager to brutalise or shoot prisoners.

To combat the bandits (estimated at 600-1,000 men), the Marines relied primarily on small patrols, usually numbering less than thirty men under a lieutenant or sergeant. These patrols were often mounted for greater mobility on locally procured horses, and stayed in the field for days, or even weeks at a time. Their objectives were twofold: to cover the bandit infested areas so thoroughly that the bandits would be unable to avoid them; and, by their small numbers, to lure the enemy into attacking them. Because of Marine firepower and unit discipline, the resulting engagements, in which the bandits sometimes outnumbered the Marines by as much as ten to one, usually ended with more bandits down than Marines. Sometimes, senior officers carefully directed and co-ordinated these patrols.

During 1918, for example, Lieutenant-Colonel Thorpe established a specific patrol zone for each company of the 3rd Regiment. At other times and in other districts, however, patrols went out more or less at random, or in response to intelligence reports or bandit contacts.

Patrols and Ambushes

Such patrols, if guided by timely and accurate information, were sometimes able to locate and attack bandit groups, even surprising them in their camps. On 20 February 1919, for example, a patrol led by Captain William C. Byrd, acting on what proved to be very reliable information from local sources, surprised a bandit camp in the mountains. In the ensuing engagement, the Marines killed 12 of a gang of 50 bandits and captured large quantities of arms and ammunition. More often, such Marine expeditions found only empty campsites, or exchanged shots with the rear-guards of fleeing gangs. "Most of our contacts," wrote Colonel Thorpe "developed from the enemy's attacking. It was looking for a needle in a haystack to expect to find the enemy in the dense brushwood or in the network of mountain trails . (Quoted in Fuller and Cosmas, 1974, 37) These contacts took the form of ambushes, or of hit and run night attacks on Marine camps.

A typical ambush was that which took place near Hato Mayor on 22 March 1919. There, a gang of about 125 bandits lay in wait for Second Lieutenant Harold N. Miller's nineteen-man mounted patrol at a point where the trail along which the Marines were riding turned sharply to the left to avoid an animal pen. Part of the gang occupied the pen, which was over-grown with brush, and from which they could fire directly down the trail into the Marine column; and the rest took post in the brush along the side of the trail to the Marines right. Both groups opened a heavy, but ill-directed fire as the Marines approached.

Lieutenant Miller dismounted his men, formed a skirmish line, and returned fire with rifles and a machine gun, which concentrated on the animal pen. The machine gun quickly silenced the riflemen in the pen and the Marines rushed the other bandits, who fled, and then halted and opened fire from the far side of a small clearing. But the fire of the machine gun again forced them to retreat and the action, which had lasted about forty-five minutes, came to an end. The Marine patrol suffered no casualties and estimated bandit losses at about fifteen.

When the bandits had enough of an advantage of numbers or position, they sometimes rushed the Marines with machetes and knives, initiating short but savage hand-to-hand clashes. On 13 August 1919, for example, at a river crossing, a large group of bandits surrounded a four-man patrol, under Corporal Bascome Breedon, and attacked them at close range with guns and knives. The Marines defended themselves, killing and wounding several bandits, but only one Marine, Private Thomas J. Rushforth, survived. Wounded in both hands and in the hip, Rushforth managed to mount a horse, fight his way through the enemy, and ride back to the nearby Marine camp for reinforcements. Actions of this intensity were rare, for most attempted bandit machete rushes collapsed quickly under Marine rifle fire. In the first week of September 1918, for example, a river crossing attack by bandits on a ten-man Marine patrol resulted in disaster for the bandits, most of whom were cut down by Marine fire while charging with machetes.

By the beginning of 1919, it was clear that 2nd Marine Brigade, which then had a strength of 1,964 men, would have to be reinforced if banditry in the Dominican Republic was to be stamped out.

Marine 1st Air Squadron

Accordingly, the Corps commandant dispatched to the republic the 15th Regiment and the 1st Air Squadron, which brought brigade strength up to just over 3,000 men. Equipped with six JN-6 (Jenny) biplanes, the 1st Air Squadron began operations from an airstrip hacked out of the jungle near Consuelo, about twelve miles from San Pedro de Macoris. In 1920, the squadron moved to another improvised field near Santo Domingo City, and was re-equipped with DH-4Bs. These single engine two seater biplanes, improved versions of a British designed World War I day-bomber, proved sturdy, manoeuvrable and versatile. And they met the demands of the squadron's varied missions more effectively than the JN-6s.

From the airstrips at Consuelo and Santo Domingo, the aircraft of the squadron flew over mountainous Seibo province, scouting for bandits. Occasionally, they were employed in a ground attack role. When, for example, a suspicious aviator spotted a Dominican carrying a rifle scurrying below, he would toss a home-made explosive from the plane and "bomb" the target. To protect themselves from return fire, the aviators sat on cast-iron stove lids.

One comparatively successful air to ground attack was that which occurred on 22 July 1919, when Second Lieutenant Manson C. Carpenter and his observer and rear gunner, Second Lieutenant Nathan S. Noble, flying in response to a telephoned report to the air base of a ground skirmish near Guaybo Dulce, caught about thirty mounted bandits fleeing across an open meadow. Carpenter launched a strafing attack, diving to an altitude of 100 feet and manoeuvring so as to bring both front and rear cockpit guns to bear. As the Lieutenant climbed to regain altitude before beginning a second strafing run, the bandits scattered into the trees bordering the meadow. On their second pass over the now empty area, the Marine aviators counted six bodies on the ground. Such attacks were rare in the bandit war, as 1st Squadron lacked any rapid means of communication between its planes and ground troops, and therefore neither the transmission of current intelligence, nor the co-ordination of field operations was possible.

The squadron's real value lay in its supporting services. Planes carried military mail and personnel rapidly from the capital city to various outlying posts. Sometimes they delivered supplies to, or evacuated wounded men from remote units. In 1922, they helped ground commanders control the operations of widely separated patrols by dropping messages to them from the air and keeping regimental headquarters informed of their whereabouts. "All in all, while Marine aviation did not prove to be a decisive combat arm in Santo Domingo, it accomplished enough in other areas to establish its value - indeed its indispensability - to Marine forces operating on the ground." (Fuller and Cosmas, 1974, 41)

In mid-1922, in a summary of operations, the commander of 2nd Brigade reported that, since 1916, the brigade had had 467 bandit contacts, in which they claimed 1,137 bandits killed or wounded for a Marine loss of 20 killed and 67 wounded. For their part, the Guardia Nacional, between 1917 and 1921, had 122 bandit contacts, in which they claimed 320 bandits killed or wounded for a Guardia loss of 3 officers and 24 enlisted men killed and 1 officer and 46 enlisted men wounded. Yet banditry still continued in 1922, mostly in the eastern district. If anything, the bandits became harder to track down because, after 1921, they avoided collisions with even small Marine patrols, and concentrated instead on terrorising the peasants and sugar estates.

Marine officers in the Dominican Republic attributed their lack of success, up to this point, in eliminating banditry to three main problems:

- 1: The continuing difficulty of obtaining accurate current intelligence on

bandit movements and positions.

2: The brigade's lack of a rapid means of communication between its scattered units. Until well into 1919, none of the companies operating against the bandits had field radios.

3: The absence of effective planning and co-ordination of Marine patrols. Most of the time regimental and even company commanders had little idea of where their patrols were. Sometimes patrols from two or three commands might be operating in the same locality, totally unaware of each others presence.

New Intensity

The anti-bandit campaign, which had been hampered hitherto by lack of money and imagination, took on a new intensity and cohesion late in 1921 and early in 1922. Then, with American withdrawal from the Dominican Republic imminent, Brigadier General Harry Lee, the commander of 2nd Brigade, and Colonel William C.. Harlee, commanding the 15th Regiment, launched a systematic drive to stamp out banditry in the provinces of Seibo and Macoris. In the 15th Regiment, the lack of field communications, which had hampered previous operations, had been remedied by late 1921. Every company now had a radio set at its headquarters, plus one or more portable field sets. Where radios could not be used, pilots of the 1st Air Squadron could drop messages to ground units.

Exploiting these assets, the 15th Regiment, between 24 October 1921 and 11 March 1922, conducted nine well planned, skilfully run cordon operations to seal off and screen entire village populations for bandits. The Marines would surround a village in the early morning, then a mounted company, accompanied by a special unit of Spanish-speaking Mexican and Puerto Rican Marines, would gallop into the village and question all the villagers, usually with the assistance of the local prostitutes, who seemed to know most of the bandits. With no casualties, the 15th Regiment screened more than 2,000 people, holding more than 600 for the military government's provost courts. Most of those held were later convicted.

On 5 March 1922, General Lee ordered the abandonment of the cordon system, partly because it had met with vehement opposition from Dominican civilians, but largely because it had failed to trap the bandit leaders and their hard-core followers, whose depredations actually increased during February and March 1922. Cordon operations were replaced by carefully co-ordinated patrols, led by experienced Marine officers and NCOs, who knew the country and the bandits. Within less than a month, these patrols had seven contacts with the enemy, four of which resulted in heavy bandit casualties.

Also early in March, General Lee authorized the formation of small civil guard units at Consuelo, Santa Fe, La Paja, Hato Mayor and Seibo. Each unit was composed of about fifteen Dominicans, who had been recommended by their municipal or sugar estate officials. They were usually men who, in the words of a Marine officer, "have suffered some injury at the hands of the bandits and are eager to operate against them. "(Quoted in Fuller and Cosmas, 1974, 45) Led by Marine officers, and usually reinforced by two or three enlisted Marines with an automatic rifle, the civil guards patrolled their own localities, and, with their local knowledge and strong motivation, quickly produced results. Between 19-30 April, they had six major contacts, which, wrote General Lee, "fairly broke and led to the disintegration of the bandit groups. In all of these contacts the bandits suffered severe casualties and losses." (Quoted in Fuller and Cosmas, 1974, 45)

The combination of intensified Patrolling and civil guard operations proved too much for the remaining bandits. In April, a group of prominent Dominicans, acting under the authority of the US Military Governor, negotiated the surrender of one of the most notable bandits still in the field. Subsequently, during an armistice granted by Lee, seven bandit leaders gave themselves up, along with 169 of their hard-core followers. In return for coming in voluntarily, they received for their crimes sentences of imprisonment and hard labour, which remained suspended during their good behaviour. By 31 May 1922, organized banditry had ceased in the eastern district, and the Marines handed over responsibility for security to the new Dominican Policia Nacional (formerly the Guardia Nacional).

The anti-bandit campaign in the Dominican Republic gave a generation of Marine officers valuable experience of counter-guerrilla warfare. Eventually, some of the lessons they had learnt would be applied in Nicaragua, where the Marine Corps found itself pitted against an enemy far more formidable than the Dominican bandits.

Sources

S.M. Fuller and G.A. Cosmas, Marines in the Dominican Republic, 1916-1924,

USMO, Washington, DC, 1974.

L.D. Langley, The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean,

1898-1934, University Press of Kentucky, 1985.

A.R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine

Corps, Macmillan, New York, 1980.

Additional Notes on U.S. Occupation of the Dominican Republic 1916 - 1924

Back to Table of Contents -- El Dorado Vol IX No. 1

Back to El Dorado List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The South and Central Military Historians Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com