|

Bonaparte after Brumaire and the Operations in Germany and Italy

After the "coup d'etat of 18th of Brumaire, Year VIII of the Republic,

(November 9-10, 1799), Bonaparte established a three-man government, the

Consulat, with himself as First Consul. The unpopular Directorate had left a

government apparatus far from efficient and lacking popular support. In

addition, the government's finances were in shambles and the army, while

steadily improving, was in an equal state of disorganization because of

chronic shortages. He started reforms immediately, but for the present,

Bonaparte had to deal with the military situation and face the Second

Coalition. [1]

The Directory was ill prepared to face a coalition greatly outnumbering

its armies. In addition, these scattered armies had no unified command.

Hostilities had started in Italy in November 1798 and the Neapolitan army, as

well as that of the Papal states, was quickly overun. Austria declared war on

March 12, 1799. Jourdan had already crossed the Rhine with a much

understrength command [2] Jourdan

should have resigned as he was to lose his reputation in the process. Arch

duke Charles had a huge superiority. His total forces facing Jourdan on the

Danube and Massena in Switzerland were 165,000. He faced Jourdan with

some 80,000 troops: 53,900 infantry and 23,000 cavalry. [3]

Jourdan advanced through the Black Forest and soon came in contact

with the more numerous Austrians. He was speedily defeated by Charles on

March 21 at Ostrach and again on March 27 at Stockach, while Massena

repulsed on March 23 at Feldkirch. Jourdan retreated in haste. Massena was

further defeated at the first battle of Zurich. On April 5, the Austrians under

Kray won another victory at Magnano and made their junction with Suvarov

and his Russians. Together, they swept the French out of Italy. Furthennore, the Bntish had landed in Holland and the royalists were once more in open revolt in several part of France.

Surprisingly, the Directory reacted energetically. The army effectives

were steadily increased. Brune was able to hold and then force the British to

evacuate Holland. Thus his forces could now be used to subdue the

insurrections in France and reinforcements poured to reinforce Massena.

[4]

In addition, the Austrians committed a major blunder by moving north

the bulk of their forces and attacking Mannheim instead of supporting

Suvarov in Switzerland. Consequently, Suvarov, lacking the necessary

effectives to hold Massena, was defeated by that brilliant general at the

second battle of Zurich on September 26-27.

Consequence

The consequences of Suvarov's defeat were enonnous. After that defeat,

Suvarov was recalled to Russia by Tsar Paul the 1st and Russia withdrew

from the coalition. Massena's victory had disintegrated the coalition and

altered the tactical situation of the other fighting fronts. On October 28, the

war minister was able to tell the Excutive Directory that the Republic was

now superior to his enemies and could take advantage of its recent victories.

In a few weeks, a steadily deteriorating military situation as the French had

been ousted from Italy and were barely holding in the East, had been

completely changed. With the Russians out of the way, Massena was now in a

position of one of three objectives. The Grisons, Swabia or Lombardy.

Then came Brumaire and Bonaparte took over the direction of the

operations. In fact the preliminary work had been done for him by the armies

of the government he had overthrown. He did not have to worry about the

Russians in Italy and Switzerland, the British and Russians in Holland, or the

royalists in France. Hence, he was able to concentrate the bulk of his forces

against the Austrians in Italy, an idea that had originated during the last days

of the Directory. [5]

Neverthless, the First Consul strengthened the army by forming some

army corps, reorganizing some units and forming an Army of Reserve. In

May 1800, he led the army of Reserve across the Alps. The brilliant Spring

Campaign of 1800 was about to start. He occupied Milan on June 2 and

threatened the Austrian line of commucations. He arrived too late to relieve

Massena, who was besieged in Genoa and was forced to surrender on June 4.

Bonaparte's forces numbered 60,000 vs. 72,000 Austrians under Melas.

In a maneuver on the rear, Melas was forced to fight at Marengo where he

was defeated. The next day Melas signed an armistice.

In Germany, the victories of Stockach (May 3, 1800) and Moskirch (May 5)

followed by that of Hochstadt (June 19) won by Moreau over the Austrians

under General Kray forced the Austnans to suspend hostilities until

November.

As soon as the armistice ended in Germany in November, the Austrians

under Archduke John (who had replaced Kray) resumed their offensive but

were decidedly defeated at Hohenlinden on Decamber 3 by Moreau. That was the end of the

Second Coalition and Austia signed the Peace of Luneville in February 1801.

The Treaty of Amiens was signed on March 27, 1802 with England. Now

the First Cansul had a free hand to implement his reforms that led to the

organization of the Grande Armee.

Bonaparte's Reforms

The First Consul inherited from the Directory an army, or more exactly

several armies which were more or less independent from one another,

unequally trained and commanded. From these armies of unequal values, but

partially composed of the veterans of the Wars of the Revolution, he was

going to form by a series of reforms an extraordinarily homogenoous and

coherent block that would become in a very short time the famed Grande

Armee.

Bonaparte's reforms were simple and were to employ the military

techniques and grand tactics created by the Republic. [6] First, the basic regiments were

consolidated into standard units by eliminating the small and numerous

formations that were found in the armies of the Directoire. Then, the

army was further reorganized by the generalization of the army corps for at

least the part of the army stationed in France proper. The brigades and

Divisions were standardized to include only one type of cavalry or infantry

[7] as early as 1796.

The Army corps was adopted to handle large formationa as it had been

found impractical for a commander to handle efficiently a large number of

Divisions. An army corps included from 2 to 4 infantry Divisions, a brigade

or Division of cavalry, some 30 to 60 guns and a detachment of engineers.

The cavalry went also, as mentioned above, into brigade and cavalry Divisions

and distributed among the army corps, and surplus cavalry went through a

complete overhaul. [8] The cavalry

until then distributed among the Divisions became part of the famous cavalry

reserve numbering 28,000 horse. [9]

An Artillery Reserve was also formed and included mostly 12 pdrs.

The ultimate reserve was formed by the Consular Guard which became the Imperial Guard in 1804. The army was reorganized into 11 corps, 7 of which forming the Grande Armee

were to be with the Guard and the Reserve Cavalry under the direct command of Napoleon duriug the Campaign of 1805. [10] Most of the corps were commanded by a Marshal (see list below). The army corps (Corps hereafter) was the largest single formation of the Grande Armee and was the foundation of Napoleon's strategy and style of warfare. [11]

Finally, the Grande Armee was placed under the direct

command of a single generalissimo, Napoleon Bonaparte, assisted by an

extraodinary efficient staff well in advance of the staffs of other armies. The

single command alone ended the sources of the problem of non-unified

commands that had plagued armies of the Revolution on too many

occasions. Christopher Duffy in Austerlitz, p. 20, says:

"The vast apparatus of Imperial Headquarters was desigaed to funnel

information to the Emperor, and to transmit his orders in the most

efficient manner. Thus the direction of the Grande Armee was

centralized to a remarkable degree.

In 1805, the new Grande Armee was animated by an unbelievable

spirit of conquest, full of the glory and prestige communicated by the

veterans of the Wars the Revolution who, in addition, widely accepted as

their chief the brilliant Bonaparte, who had become their Emperor. [12]

The Peace of Luneville and Amiens gave the Grande Armee the period of quiet necessary to implement the reforms. The training at the huge Camp of Boulogne did the rest.

One should not conclude, as is often suggested or prooffered, that the

reforms introduced in the new Grande Armee by Napoleon also

included new tactics. The Emperor had nothing to do with the tactics used by

the Grande Armee These tactics which significantly contributed to

the relatively easy victories of the Campaigns of 1805 and 1806, were based

on the so-called "impulse system." The impulse system, whose principles

had been outlined by Folart and de Saxe well before the Seven Years War, were in 1805 the result of the evolution of the tactics used by the army of the Revolution preceded by the introduction of permanent brigades and Divisions. However, the "impulse system" was

optimized by the creation of the army corps.

The Army Corps System

The idea of the army corps was not new. It had been suggested by de Saxe

and experimented with by Hoche, Moreau and others as early as 1795. For

instance, Moreau in 1795 organized his army of the Rhin-et-Moselle into 3

commands: the Right Wing under General Ferino (25,018), the Center under

General Desaix (27,292) and the Left Wing under General St.Cyr (19,271).

These "wings" and "center", although not called army corps, had the strength of

a Napoleonic corps and operated on a wide front under the orders of a single

commander, General Moreau. [14]

Like Moreau, Bonaparte in all his campaigns had also integrated his corps

under a single commander. Now, starting with the Campaign against Austria in

1805, Napoleon now was able to concentrate the bulk of the French army in a

given theater of war under a single command. Some 194,000 men composing

the Grande Armee were committed to that Campaign.

| TABLE I: GRANDE ARMEE: Effective Campaign of 1805 |

|---|

| CORPS | COMMANDER | INFANTRY DIVISIONS | CAVALRY DIVISIONS | BATTALIONS | SQUADRONS | NUMBERS |

|---|

| I | Barnadotte | 2 | 1 | 18 | 16 | 17,737 |

| II | Marmont | 3 | 1 | 25 | 16 | 20,758 |

| III | Davout | 3 | 1 | 28 | 12 | 27,452 |

| IV | Soult | 4 | 1 | 40 | 12 | 41,358 |

| V | Lannes |

2 | 1 | 18 | 16 | 17,788 |

| VI | Ney | 3 | 1 | 25 | 12 | 24,409 |

| VII | Augereau | 2 | - | 16 | 4 | 14,850 |

| Cav. | Murat | -

| 6 | - | 120 | 23,415 |

| Guard | Bessieres | - | - | 12 | 8 | 6.278 |

| Total: 194,045 |

That grande Armee operated on a wider front 260 miles (over 400

kilometers) than any army had operated before. In addition, as it will be seen

later, such a large army had never been concentrated under a single unified

command. That had become possible because of the elaborale imperial staff headed by Berthier.

With that centralized system of command, Napoleon had invented something far more important

than tactics. He had initiated a strategic system allowing a general-in-chief to command

and control many more troops than was ever possible before. During the Campaign of

1805 [15] it overwhelmed the Austrians and their

allies the Russians and 1806 the Prussians. The system was to be enthusiastically

accepted by the Prussians after 1806, the Russians after 1807 and less so by the

Austrians in 1809.

Napoleon's concept of warfare was based on principles espoused by Boourcet, [16] and others, recommended that troops move on a

wide frontage. That was in sharp contrast with the strategic concept of other countries which,

in l805-1806, moved troops on a close frontage. The strategic concept was to seek the enemy

and to force him to a decisive battle, as quickly as possible. Consequently, the grande Armee moved its corps on a wide frontage [17] on several

axes. The principle of the battaillon carre as showm on the diagram

was simple. It consisted of moving army corps over wide distances and wide

frontages in loosely drawn but carefully coordinated formations within supporting

distance of each other.

Our diagram at right shows 4 corps moving forward at one day's

march from each other.

Our diagram at right shows 4 corps moving forward at one day's

march from each other.

Large Diagram (slow: 29K)

Corps # I is the advance Guard, Corps #2 and #3 are the left

and right flanks while Corps #4 is the reserve. The formation is screened by light

cavalry from the Cavalry Reserve whose primary mission is to seek the enemy.

[18]

The adjacent diagram shows the cavalry screen had located the enemy on the left flank. It did not matter where the enemy was discovered. If ahead the Advance Guard would engage the eneny. If on the flanks, like at Jena, a flanking corp (that of Lannes) would do the initial pinning. Other strategic functions could be used in other circumstances, always with the cavalry

screen on an advance on a wide front. The location and progression of the corps were carefully controlled and based on the same principles.

When the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest corps to make contact with the enemy and pin him down in the present location.

When the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest corps to make contact with the enemy and pin him down in the present location.

Large Diagram (slow: 34K)

The rest of the army on the eve prior to the battle was assembled. [19]

The Operation of a French Corps

We have seen that an army corps was a miniature army of all arms. It was enough to engage and and resist if necessary a superior enemy for a certain time until another corps could come to the rescue. In some instances, the apparent weakness of the French force immediately engaged

tempted the enemy to move forward to attempt its destruction. [20].

Finally, the corps commander had to feed back information to the commander-in-chief.

The corps commander knew the capabilities of each of Divisions,

brigadiers, and so on down the chain of command. He also had to know the

capabilities of his troops that had been trained as per his instructions and under

his supervision. Hence, he had a homogeneous force under his command.

Finally, the corps commander's staff included a number of ADCs and often one

or more "spare" generals and capable ADCs. Each Division and brigade had also

their own small but adequately trained staff. The result was a homogeneous and

efficient military unit. [24]

Napoleon's Central Staff System

We only intend to cover the single aspect of Napoleon's complex staff system that concerns us directly. That is the part of the staff that operated under Berthier to coordinate all of the Grande Armee movements in accordance with Napoleon's orders.

A point has to be noted about these orders which would help one understand the 'secret" of Napoleonic warefare. The fact is the speed at which they were interpreted by Berthier, written, transmitted and carried out [25] The orders were carried out on average in less than 2 hours between reception and execution as shown in the table taken from Vache, Napoleon on Campaign, p. 49, Paris (1900).

The time between the arrival of an order and its execution is the time that

was required to interpret the order and transmit it to the different Divisions,

artillery and cavalry which were also somewhat distant from the orps HQ. In

the bataillon carre system, the interval from the time the order was issued to

the moment it was carried out averaged 4 hours. That was a huge improvement

over what other armies could do and combined with the marching capabilities

of the Grande Armee contributed to Napoleon's success in the field.

| Table II: Transmission and Execution of Napoleon's Orders on

Oct. 11-12, 1806 |

|---|

| CORPS | LOCATION: OCTOBER 11 |

DISTANCE FROM HQ (MILES) | DEPARTURE OF ORDER

| ARRIVAL OF ORDER | MOVEMENT STARTS

|

|---|

| Murat | Gera | 19 | 0400 hrs | 0715 hrs | 0900

hrs |

| Bernadotte | Gera | 19 | 0400 hrs | 0715 hrs | 0900

hrs |

| Davout | Mittel | 4.5 | 0500 hrs | 0600 hrs | 0700

hrs |

| Soult | Weida | 11 | 0400 hrs | 0600 hrs | 0700

hrs |

| Lannes | Neustadt | 8.5 | 0430 hrs | 0600 hrs | 1000

hrs |

| Ney | Schleiz | 12 | 0300 hrs | 0530 hrs | 0600 hrs |

| Augereau | Saalfeld | 20 | 0530 hrs | 0815 hrs | 1000 hrs |

Overall, in 1805-1806, the Allies could not come close to matching Napoleon's staff efficiency as well as the speed in the transmission of orders but that is another story.

Berthier, who had already been Napoleon's Chief-of-staff in Italy back m 1793 and had been with him in that function in Egypt and in Italy in 1799, was the man behind Napoleon's efficient staff. In 1815, Soult was Napoleon's Chief-of-staff and committed many blunders in the transmission of orders.

Differences and Similarities between the Revolutionary Divisions and the Empire

Corps System

David Chandler in The Campaigns of Napoleon, p. 159, compares Napoleon's army corps

with de Broglie's "Instructions of 1761," [26] which introduced the idea of permanent Divisions into the French army. He says:

"... if we substitute the title "Marshal" for "Lt. General," change the phrase "colunn Advance Guard" into "Corps Artillery Reserve" and disregard the outdated system of dividing the army into "lines", this passage might almost seem as the description of Davout's or Massena's Corpe d'Army of fifty years later."

We agree that there is a great deal of similarity between the de Broglie's (and the Revolution's) permanent Divisions. That has been precisely our argument in showing the permanent Divisions as the "ancestor" of the Empire's army corps. However, there was also a great deal of difference. The main difference is in their effective strength. The permanent Divisions seldom reached the effective strength of the army corps and in many occasions (such as in 1799 in the army of Jourdan) had fairly low effective strengths. On too many occasions, they lacked the strength of the army corps to carry out their mission (like Jourdan in 1799) and could

not, like the army corps, sustain a full day's combat with superior forces. In other words, they lacked the staying power of the army corps.

There is also another major difference between an army corps and a Division. The Division had a tendency to occupy too large a frontage for its effective amount of manpower. Consequently, they had to be grouped into armies, which by themselves were closer to the Empire's army corps than the Division. Colonel Elting p. 49, makes more comments on the Revolutionary Division: "...Especially when understrength, as they usually were, a Division was big enough to get into trouble but sometimes not big enough to get out of it..."

That also led Generals like Moreau to group Divisions into makeshift army

corps like the Army of Sambre-Meuse in 1796.

In addition, Divisions (and their component brigades) included a cavalry

detachment ranging from a few hundred to several thousand. There again, the

army corps was more versatile since the allocation of cavalry was variable and

not permanent. It depended on the mission assigned to the corps. The

consequence of that was the constitution of an extraordinarily efficient

Cavalry Reserve.

Marmont's comparison of Divisions and army corps is worth quoting:

..."In an army, the constant unit...is the Division. It is ordinarily

composed of two brigades, each of two regiment, and sometimes of

three, and it has, besides, two batteries of artillery and a corps of seven

or eight hundred horse. It has a complete administration. It is an army

on a small scale: it can act separately, march, subsist and fight, or it can

come with ease to take the part assigned to it in line of battle.

It was thus that the French army was organized in our first and

immortal campaigns in Italy, and also some years after. At a later

period, Napoleon, having formed corps d'armee, withdrew the cavalry

fron the Divisions and contented himself with applying to the corps

d'armee the principles of the legion. But in the corps d'armee, the cavalry

is too far from Division, it is not undor the control of the infantry

generals who conduct the battle, it is unable, in many circumstances to

take timely advantage of the disorder which arise in the eneny ranks..."

Obviously, Marmont did not see eye to eye with Napoleon and we would

further analyze his point of view, as well as that of Hoche and Moreau, at some

future date. However, Marmont's remarks on Divisions and cavalry are

controversial for two reasons. Firstly, cavalry was not allocated to an army

corps on a rigid basis but as a function of the mission given to an army corps and was assigned to Divisions (or even brigades or task forces) when necessary. Secondly, Colonel Elting, p. 49, brings up an important point:

"... The cavalry attached to the Divisions often was used up early in the

campaign; the average general didn't know what to do with it or how to

take care of it. By 1797, commanders as dissimilar as Hoche,

Napoleon, and Moreau were going back to separate Divisions of

infantry and cavalry, each with its own artillery. Napoleon was forming

Divisions of three brigades, one of them light infantry." [28]

The changes brought up by the Introduction of the Army Corps

System and a Unified Command

It is obvious that the Grande Armee was no longer a conventional

army force. But the changes it brought to the art of warfare are sometimes not

fully appreciated and even denied by some historians. In contrast to the other

armies of the period, the French army was subdivided into (more ar less)

permanent Divisions and brigades, while, the Austrian, Russian armies and

other armies of 1805 were 'regimental armies' organized on an eighteenth

century pattern. [29]

In other words, they had no permanent or even semi-permanent subdivisions

such as the brigade, Divisions and army corps which provided the French with

convenient and efficient intermediate stages between the mass of individual

regiments and the command of the army. For the Allies, terms like columns,

corps, Divisions, and brigades signified no more than an ad hoc arrangement of

battalions or regiments. Hence, in these armies, a wing commander, or

whatever it was called, had to send separate orders to each regiment under his command.

On the approach to the field of Austerlilz, the French emigre General

Langeron, who was now in Russian service but who had been in French service

and knew the advantage of the Divisional system, was astonished to see that

column commanders were not given the slightest opportunities to know their

units and build some degree of trust.

On the approach to the field of Austerlilz, the French emigre General

Langeron, who was now in Russian service but who had been in French service

and knew the advantage of the Divisional system, was astonished to see that

column commanders were not given the slightest opportunities to know their

units and build some degree of trust.

Large Map of Allied Plan (slow: 70K)

He describes the situation:

"...In these five marches, the individual general never commanded the

same regiments from one day to the next. [30]

Perhaps Langeron's obervation reflects extreme situations, but it clearly

shows the basic problems of the old system. Commanders were shifted around

much too often and had not the opportunity to familiarize themselves with their

command.

For instance at Austalitz, the Russian General Prebyshevsky, of one of the

Allied column, was introduced to his command just one day before the battle.

[31]

The armies' cohesion suffered. The French permanent Divisions had the

further advantage of allowing the units of a given command to work with each

others and consequently increase their level of confidence.

The old command system lacked the decentralization in command possible

with the corps system. Each Corps operated independently with its own,

adequate, trained staff, capable of quickly issuing orders through the chain-of-

command down to the battalion to implement the general orders of the

commander-in-chief. Hence, the system was capable of better and quicker

control than the old system.

With the new system, the army commander had to issue orders only to his corps commanders and those corps commanders only to their Division commanders. Consequently, these commanders could act more freely since their staff work could be handled far more rapidly the transmission of orders to face tactical situation. In other words, commanders of the armies using the old system had many more difficulties in controlling their armies duriug the course of a battle.

In addition, the commander-in-chief of the old system were in the habit of

giving very detailed instuctions to their subordinates. [32] In addition, the Allied subordinates, in the habit of following blindly

their orders, in many occasions, lacked personal initiative. No such thing took

place in Napoleon's army. The corps commanders were given a clear and

precise mission and seldom detailed orders on how to accomplish it. The co

nduct of the operations at the corps level was the responsibility of the Corps

commander and so on down the chain of command.

At Austerlitz, we see Napoleon controlling the development of the battle

by issuing orders to the corps (or task force) commanders only at critical

times, leaving the detail of the application to his subordinates. Christopher

Duffy in Austerlitz, p. 165, makes a very pertinent point:

"...in 1947, M. de Lombares performed a service of fundamental

importance when he uncovered the development of Napole on's

intentions concerning the battle, and demonstrated how little the

action as fought corresponded with the Emperor's plan. Napoleon's

power of improvisation now became all the more important: the IV

Corps advance on the Pratzen, which was planned as just one element

of a much wider sweep, therefore became the chief instrument of

victory."

What is pertinent to us is that the flexibility of Napoleon's system of command

allowed the necessary transmission of orders to quickly take place. Such

flexibility was denied to the Allies. Once the French showed up on the Pratze,

Kutusov was unable to redirect his army.

During the same time, the Allied army numbered between 80,000 and

89,000 troops. The Austrian General Weyrother, at the instigation of Czar

Alexander, had imposed his battle plan on Kutusov. Basically, the Allies were

to pin the French right flask while Bagration with 13,700 was to hold the

French in the North. His effort was to be supported by Liechtenstein, the 5th

column and the Russian Imperial Guard.

The rest of the troops were to turn the French right. In fact, Kutusov, in

order to implement Weyrother's plan, had split his command in two, leaving

the center denuded. Consequently, the Allied army was divided into 8 different

columns. Every column had received detailed orders on what they had to do

and how to do it. Once the orders were issued, Kutusov was completely unable

to control his army after the French appeared unexpectedly on the Pratzen with

the exception of the 4th column which was nearby and more or less under his

direct command and line of sight. The rest of his army operated on their own

for the rest ofthe battle with the result we know. [34]

Although the major states had military establishments numbering over

200,000, the armies they fielded under a single command prior to the

introduction of the corps system had been relatively small and few exceeded

50,000. It appears that the maximum effective strength that could be

controllod by a single commander was in the order of 80,000. Martin van

Creveld in Command in War, p.88: says:

"From the dawn of recorded history until shortly before 1800... Field

armies numbering as many as eighty thousand men remained exceptional

throughout the period and once assembled, they could not be effectively

commanded."

A quick look at specific battles of Table 3 show that Frederick the Great

commanded 65,000 at Prague and 50,000 at Hohenfriedberg, Kunerdorf and

Torgau but less than 50,000 in all his other battles. The Austrians had 84,000 at

Leuthen, 80,000 at Hochkirch and 64,000 at Prague but less than 50,000 in the

other battles. We can run the same survey for the Wars of the French

Revolution and find that the battles were fought with much smaller effective

than those ofthe Empire. Very few battles were fought with combatants above

50,000 on either side and most were far below that number. As soon as larger

effective were involved, the French generals (Hoche, Moreau) adopted a crude

form of the army corps.

| Battle | Prussians | Austrians (and/or Allies) |

|---|

| Mollwitz (4/10/1741) | 22,000 | 18,100 |

| Chotusitz (5/17/1742) | 24,500 | 29,000 |

| Hohenfriedberg (6/4/1745) | 50,000 | 66,000 |

| Soor (9/30/1745) | 22,562 | 41,000 |

| Kesseldorf (12/15/1745) | 31,000 | 31,200 |

| Lobositz (10/1/1756) | 29,000 | 34,500 |

| Prague (5/6/1756) | 65,000 | 62,000 |

| Kolin (6/18/1757) | 32,000 | 44,000 |

| Gross-Jagerdorf (8/30/1757) | 25,600 | 70,000 |

| Rossbach (11/5/1757) | 42,000 | 22,000 |

| Breslau (11/22/1757) | 28,000 | 84,000 |

| Leuthen (12/5/1757) | 33,000 | 65,000 |

| Zorndorf (8/25/1758) | 36,000 | 43,300 |

| Hochkirch (6/14/1758) | 31,000 | 80,000 |

| Kay (7/23/1759) | 28,000 | 40,000 |

| Kunerdorf (8/12/1759) | 50,900 | 59,500 |

| Leignitz (8/15/1760) | 30,000 | 24,000 |

| Torgau (11/3/1760) | 50,000 | 53,400 |

The solution to maximizing the size of large armies was to increase the number of columns and detachments. Archduke Charles during the War of the Second Coalition, at the beginning of the Campaign of Germany, had a very large army numbering 165,000 and promptly divided it into several commands, keeping only under his direct control some 80,000.

In contrast, during the wars of the Empire, precisely because of the

flexibility in comman resultmg from the introduction of the more versatile

corps system and of a mere elaborate central staff, [35]

Napoleon controlled more than 100,000 in several of his battles: 175,000 at

Smolensk, 110,000 at Lutzen, 175,000 at Bautzen, 167,000 at Wagram,

160,000 at Gross-Gerschen, 133,000 at Borodino, 100,000 at Dreaden and

195,000 at Leipzig. So did his opponents after they improved their central

staff, which does not mean that such large effective were engaged in all the

battles of the Napobonic wars.

A quick study of the effective engaged during the campaign of 1805 shows

that the 50,000 French troops were in northern Italy under Massena and

18,600 in central Italy under Gouvion St Cyr and 30,000 remained on the

Channel coast.

The French troops committed to the decisive operation in Germany against

Austria numbered 194,000 men under the direct control of the Emperor, at

least until Mack's surrender at Ulm. It was the first time in history that such a

large number of soldiers were under the direct control of a single commander.

And that commander had only one objective--the destruction of the enemy.

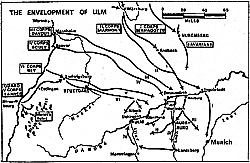

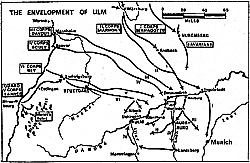

Large Map of Ulm (slow: 82K)

Large Map of Ulm (extremely slow: 294K)

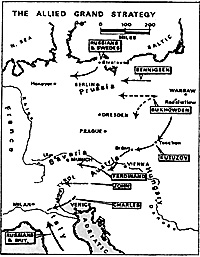

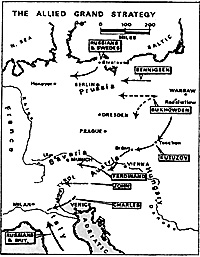

On the Allied side we find a different story. In 1805, the initial Allied plan

called for an offensive on a very large front as shown on the map, stretching

from the Baltic to the Mediterraneen. The main Russian effort was to be

directed toward northern and central Germany. General Benningen ready to

move through Prussia with 40,000, and General Kutusov 50,000 marching

toward the Danube to support the Austrians. General Buxhowden with an

additional 50,000 was available - in theory - to support either generals.

Archduke Charles with a force of about 50,000 was to hold northern Italy

while 9,000 British troops and 25,000 Russians from Corfou were to land in

Naples. Another diversion was planned in northern Italy by a mixed command

of 20,000 Russians and 16,000 Swedes. We should not forget the unfortunate

Mack's command which included some 50,000. On the Allied side, one point

is flagrant, it is the number of small commands which were not operating like

the Grande Armee under a single command or generalissimo, but as

independent commands. That demonstrates very precisely the point we are

trying to make about the limitation of the fielded commands around a

maximum of 50,000 men before the introduction of the Corps system in the

Allied armies.

The Allies, after they also introduced the corps system or variations of it,

also became capable of commanding and controlling larger armies, whenever

necessary, not only in battles but also in operationes. Kutusov had 120,000 at

Borodino. Blucher had 80,000 at the Katzbach, 100,000 at Craonne, and

128,000 at La Rothiere. At Leipzig, the Allies concentrated no less than

320,000. Obviously, a revolution of some kind had taken place.

The reason that large armies in the old system could not be effectivdy

commanded and controlled once fielded was due to sevaal reasons. Firstly, the

commander-in-chief's staff was very often insufficient and lacked enough

ADCs to carry a multitude of orders to the different ad hoc subdivisions in the

army. An army in single, fairly close and compact bodies directly under the

eyes of the commander-in-chief. [36]

The analysis of the battles fought before 1805, as shown above, suggests

that the maximmn nmnber that could be effectively commanded was not to

exceed 80,000 and preferably not in excess of 50,000. Usually, when an army

commanded 80,000, it was broken up and one or more wings were given a

secondary mission to perform tasks of secondary importance not subject to

close control. Secondly, since their cavalry was distributed among the troops,

these armies lacked the strategic versatility due to the lack of long range recon

forces.

In 1805, the unfortunate Mack at Ulm had no idea of what was about to take place until it was too late. Thirdly, these armies depended on a very large supply train system, and since armies were concentrated, it wss very difficult to fit such a lage train into a relatively

narrow frontage. The dependence on the supply train considerably slowed the rate of advance of such armies. [37] Napoleon's army, living off the land, did not depend on large supply trains and was not handicapped by them.

Finally, with the new corps system (and of independent Divisions), defensive and offensive actions were no loger the effort of an entire line under the direction of a single commander attempting to control the movement and actions of an entire army. The attacking or defending actions were broken up into a series of individual actions or series of "impulses" on the enemy

position. These impulse actions were now the responsibility and under the control of the commander who controlled, brigades, Divisions and corps. Hence, the role of the commander-in-chief was greatly simplified and he no longer had the task of directly controlling his troops at lower tactical levels.

He was now in a position to hand out the control of larger forces to individuals.

In addition, the 'impulse" system promoted the cooporation of the three arms, which had been practically impossible with the linear system [38]

Conclusion

The lineage in the permanent Divisions introduced by de Broglie during the Seven Years War and perfected before 1789 and the War of the Revolution has been established.

The introduction of the corps system greatly amplified the business of directing an

army on campaign and Napoleon was going to develop the system to its maximum

efficiency. The corps system revolutionized the art of war and hence, the new

system allowed a greater number of troops to be moved much faster and over a wider frontage than before without losing command and control, greatly simplifying the task of the commander-in-chief in the process. That was the main achievement of the chain of events started during the

Seven Years War. It was a revolution in strategy which became only possible with the

development of an important staff system similar to Napoleon's huge Imperial Staff and HQ

that directed the Grande Armee.

Many historians, rightfully, have pointed out that most of the tactical reforms

such as columns, etc. introduced in the French army by the Regulations of 1764

1791, etc., had been tried by Frederick the Great. But that was not the case for the

permanent Dinsions and the army Corps. Frederick never tried nor anticipated the

the Divisional system and its later development the army corps. Christopher Duffy

in his recent second edition of The Army of Frederick the Great, p. 211:

"At first sight it might appear that Frederick, as military man, should have

been alert to some very important changes which were already in progress

concerning the way armies were directed in the field. Until the third quarter of the eighteenth century all armies were 'regimental', in that no kind of stable command structure existed between the commander of a given army and the mass of the individual regiments. In 1760, however, the French organized their army in Germany into a number of multi-regimental 'divisions', two of cavalry, and four of infantry, each of the divisions standing

under the command of a Lt Gen. This greatly simplified directing an army on Campaign, and Napoleon was going to develop the principle into the multi-divisional corps, or miniature

armies, which swept through Europe in 1805.

There is no sign that the nascent divisional system ever came to Frederick's attention."

Perhaps instead of concentrating on the difference between French tactics and that of their opponents, wargamers should concentrate more on the command structure

of the armies and on the speed of the transmission of orders. As Chandler says in his Dictionory of Napaleonic Wars: "All in, the corps d'armee system was one of the major factors in Napoleon's success."

One thing is for sure, in the first two campaigns of the early Empire, which led

to the virtual destruction of the Allied armies in succession at Ulm, Austerlitz in

1805 and Jena and Auerstadt in 1806, the French army at his best and far in

advance over that of its continental opponents. Thesee easy early victaries, achieved

at very little cost, were not simply the product of Napoleon's personal genius, but

just as much the results of the new French methods of combat after about thirteen

years of sporadic development during the wars of the Revolution.

But the Allies were to quickly catch up. As early as 1807, the Russians were

able to make a better stand at Eylau which was far from an easy victory.

Sources:

The subject we have covered is extensive. It is only the "40,000 foot view" of the

organizational evolution that took place in the French army between the Seven

Years War and the Empire, which, as we shall see, changed the face of

warfare through the introduction of the Division and ultimately the army Corps.

Our series is the result of many years of research, some of which has been

published during the last 18 years in EE&L. The main sources we have used are

mostly French, with some exceptions. These sources have been carefully

corroborated and most, like Belhomme's Histoire de l'infanterie en France, use

data from the French archives at Vincennes and the Archives Nationales. We consider them extremely reliable. Our main sources were:

Belhomme, Lieutmant-colonel, Histoire de l'infanterie en France, Paris, 1893-1902.

Latreille, Capitaine, L'armee et la Nation a la fin de l'ancien regime, Paris, 1914.

Colin, Capitaine Jean La tactique et la discipline dans les armeees de la Revolution,

Paris, 1902.

---- L'infanterie au XVIIIe siecle, la tactique, Paris, 1907.

---- The Transfonnation of War, Translation, London 1912.

Quimby, R. S., On the Background of the Napoleonic Warfare, Columbia University

Press, New York, 1957.

Jomini, Lieutenant General, Histoire critique et militaire des guerres de la

Revolution, Paris, 1822.

Archduke Charles, Principes de la stratigie developpes par la relation de la

campagne de 1796, Brussels, 1840 (translated from the German by Jommi). This

source not only gives Archduke Charles' version of the Campaign of 1796, but also

includes Jomini's version of the campaign Jourdan was the general commanding

the French forces during the campaign.

Phipps, Colonel R.W., The Armies of the First French Republic, 5 volumes, Oxford University Press, 1926-39.

Chandler, David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, The MacMillan Co, New York, 1966.

Duffy, Christopher, Austerlitz, Seeley Service & CO. London, 1977.

------, The Army of Frederick the Great, Hippocrene Books, 1974.

Nafziger, Gearge, A Guide to Napoleonic Warfare, privately published, l995.

Elting, Colonel John R. Swords Around the Throne, New York, 1988.

Marmont, Marshal, The Spirit of Military Institution, or Essential Principles of

the Art of War, Philadelphia, 1862.

Nosworthy, Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Hippocrene, New York, 1990.

---------, With Musket, Cannon and Sword, Sarpedon. New York, 1996.

Van Creveld, Martin, Command in War, Cambridge, 1985.

Footnotes

[1] The Second Coalition included Great Britain, Russia, Austria, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Naples, and the Papal States. With the exception of Austria and Russia, the coalition lacked substantial land forces. Austria and Russia were to bear the land fighting.

[2] The Directory had assured Jourdan that he would have 100,000 men provided with a park of artillery, a magazine of provisions, etc., necessary for such a campaign. His left flank was to be protected with an army of obervation of some 38,000, while Massena with some 24,000 men was to operate in Switzerland and protect his right. But tthe incompetent Directory was unable to keep its promises. At the opening of the campaign, Jourdan's

command included only 36,994 men and the army of observation supposedly protecting its flank was only 10,000 and much too weak to do anything significant. Jomini, Vol. XI, p. 96.

[3]Phipps, Vol. V. p.35.) Hence,

Charles enjoyed a 2:1 superiority over Jourdan. The rest of the Austrian forces were

sent against Massena.

[4] Massena's army had been reinforced through the summer and by September numbered 88,768 men, including 4,934 Helvetian troops. Massena reorganized the Army of the Danube into eight combat Divisions, a reserve Division, and an interior Division. He was ready to strike.

[5] Quest for Vistory, p. 282.

[6] In his remarkable Quest for Victory, Prof. Steve Ross argues quite convincingly that "Still, despite its final collapse, the Republic achievements were impressive. Amidst war and political turmoil, France built the best army in Europe, withstood the assault of the great powers and made extensive conquests. France then defeated a Second Coalition and in 1799 stood as the most powerful single nation in Europe. Had Bonaparte been satisfied with remaining first among equals rather than trying to reduce all of Europe to vassalage, he might today be remembered as a great soldier statesman instead of a romantic genius who led a triumphant nation into catastrophe." Of course, such a statement, while overall very true, can be further debated and argued by ardent Bonapartists. The very same was argued by French historian Jean Tulard in his Napoleon.

[7] By a Consular decree dated September 23, 1803, the demi-brigades were once more called regiments. We have seen in EE&L vol. 3 no. 1 that the concept of army corps was already used by Moreau and Kleber.

[8] See EE&L #5, pp.40-45, "Les Cuirassiers du Roi: The First Consul Cuirrasiers and the French cavalry reforms of 1803".

[9] The Cavalry Reserve included two Divisions of currassiers, 4 of dragoons, and the rest of the light cavalry. It was supported by 24 guns.

[10] In 1805, the Grande Armee included a core of seasoned veterans consisting of about 25% of the effective manpower who had seen service since the early days of th Revolution and another 25% who had joined the army during the Campaigns of l799-1800. The rest were conscripts who had been extensively trained at the Camp of Boulogne.

It is interesting to note the enthusiasm of the troops had somewhat decreased for the Campaign of 1806 against the Prussians.

[11] See Anatomy of Victory p. 350-2. In additio, the system favored the tactical cooperation of the three arms, which was something new. in addition, the system allowed different units (regiments, brigades, divisions,and corps) to

function as semi-independent entities.

[12] Archduke Charles, Histoire de la campagne de 1796, p. 68. The documents are traceable to French archives.

[13] However, the Army of ltaly under Massena was not organized into army and kep the old Divisional organization. more on that in future issues.

[14]Christopher Duffy, Austerlitz, pp. 13-14.

[15] The unfortunate Mack, although he had 70,000 men at his disposal, couting the outlying detachment of Jellacic and Kenmeyer, had only 43,000 men around Ulm. he estimated Napoleon could not muster more than 80,000.

[16] Bourcet was the mind behind

moving the French army in several columns during the Seven Years War that led

to permanent Divisions. See part I of this series in EE&L Vol. 2 No. 14.

[17] In 1806, at the beginning of the campaign against

Prussia, the battalion carre had an initial frontage of 200 kilometers (125 miles), soon

reduced to 45 kilometers (28 miles) to go through the Thuringenwald and then re-expanded

to 60 kilometers (38 miles) during the advance to Leipzig.

[18] The second

mission was the screen the battalion carre from the enemy.

[19] By "assembly" Napoleon meant the placing of his different corps within marching distance from the intended battlefield, Chandler: p. 151.

[20] This was the case on Oct 13, 1806

at Jena, when the Prussian Prince Hohenlohe believed, after Lannes had crossed

the Saale to occupy an exposed position on the Landgrafenberg, that he was dealing with an isolated flank of Napoleon's army.

[24] Divisions and brigades were reasonably permanent formations but corps were not. For instance, outside of Ulm on Oct. 16, 1805, Lannes VIth Corps comprised the infantry divisions of Oudinot and Gazan and Treillard's light cavalry. A week later, on Oct 24, Lannes Corp contains two more infantry divisions transferred from Ney's and

Marmont's Corps and no less than three cavalry formations transferred from the cavalry reserve. This was done because Lannes' mission required an increase in infantry and cavalry strength.

[25] The orders themselves were carried

by ADCs at an average speed of 5 1/2 miles an hour, a speed that had not

changed for many years. Croveld, Martin van, Command in War, p. 88.

[26] See part I for text (Vol. 2, No. 13).

[27] Marmont's point of view on Napoleon's organization, army corps, cavalry reserve, etc. will be covered in a future article. Marmont, The Spirit, pp. 144-145.

[28] Hoche formed Divisions of cavalry and Bonaparte formed brigades.

[29] Duffy, p. 25.

[30] Quoted by Duffy on Austerlitz, p. 26.

[31] Austerlitz, p.26.

[32] It took time to write such

detailed instructions, which were often obsolete by the time they reached

the subcommanders. hence it was a bad practice. Elting, p. 48.

[33] M. de Lombares, devant Austerlitz, sur les traces

de la pensee de l'Empereur, in Revue Historique de l'Armee, III, Paris 1947.

[34] Weyrother's plan was in German and had to be translated into Russian. these translations only reached some Russian generals the day of the battle--after their movement had already begun.

[35] Command in War p. 58.

[36] At Waterloo, the Prussian central command under Gneissenau functioned better than that of Napoleon under Soult.

[37] Brunswick, during his invasion of France, stopped every 4-5 days to bake cread. In addition, the large supply trains in many cases interferred with troop movements.

[38] The rigid deployment of linear tactics by which an army was deployed in two extended lines acting in concert with cavalry on the flanks prevented the concentration of large armies since these lines had to be controlled as a whole and operated under the direct visual control of the commander.

[39] See With Musket, Cannon, and Sword

More Evolution

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 3 No. 2

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com

|

Our diagram at right shows 4 corps moving forward at one day's

march from each other.

Our diagram at right shows 4 corps moving forward at one day's

march from each other.

When the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest corps to make contact with the enemy and pin him down in the present location.

When the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest corps to make contact with the enemy and pin him down in the present location.

On the approach to the field of Austerlilz, the French emigre General

Langeron, who was now in Russian service but who had been in French service

and knew the advantage of the Divisional system, was astonished to see that

column commanders were not given the slightest opportunities to know their

units and build some degree of trust.

On the approach to the field of Austerlilz, the French emigre General

Langeron, who was now in Russian service but who had been in French service

and knew the advantage of the Divisional system, was astonished to see that

column commanders were not given the slightest opportunities to know their

units and build some degree of trust.