Editor's Note: Jim Arnold is the author of Crisis on the Danube and of the newly published companion book on the second part of the Campaign of 1809 Napoleon Conquers Austria (see the book review elsewhere in this issue).

Napoleon's Austrian campaign of 1809 marks a turning point in the history of warfare. It was the world's last campaign in which cavalry shock action had decisive tactical importance. At the Battle of Eckmühl in April and again at Aspern-Essling in May, French cavalry leaders conducted brigade and division-size charges that overthrew formed infantry and overran well-served artillery. Their charges routinely stopped cold advancing Austrian columns and carved breaches in defending lines. Because they maneuvered at speed, during battlefield crises in 1809 Napoleon called upon his cavalry to plug holes, redress setback, create opportunity, and exploit tactical success.

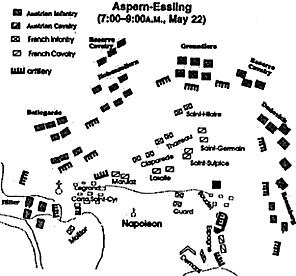

On May 20, 1809 -- the first day of Aspern-Essling -- Erzherzog Karl's ponderous, five-prong assault found the French surprised and ill-prepared. At 10 a.m., a heavily laden boat had crashed through the fragile French pontoon bridge spanning the Danube. Henceforth the French army stood riven in two, its parts seperated by raging floodwaters.

On May 20, 1809 -- the first day of Aspern-Essling -- Erzherzog Karl's ponderous, five-prong assault found the French surprised and ill-prepared. At 10 a.m., a heavily laden boat had crashed through the fragile French pontoon bridge spanning the Danube. Henceforth the French army stood riven in two, its parts seperated by raging floodwaters.

For most of the day Marshal Massena's three Divisions, numbering some 20,603 soldiers, supported by 8,554 troopers belonging to Marulaz's and Lasalle's light cavalry, d'Espagne's cuirassiers, and Nansouty's first brigade, stood with the bridge behind him broke. He happened to come across Napoleon and his staff. He saw Marshal Berthier gesture toward the Marchfeld and say, "Here is a magnificent ballroom. We will make the Austrians dance!" Girault afterwards noted that this time the marshal was mistaken, "They made us dance, and we had to pay the violinist." 1

Entrenched Camp

In Napoleon's mind the position was like an entrenched camp, with Aspern and Essling serving as bastions, and the connecting road, 2,000 yards long, acting like curtain to unite the whole. The villages somewhat sheltered the defending French infantry. In the center, here was terrain devoid of shelter -- the partially elevated road and adjacent drainage ditches could do nothing for mounted men -- dead level, and thus terribly vulnerable to converging Hapsburg artillery fire. To defend in place was to die. Maneuver alone could preserve the position.

The first challenge came from FML Friedrich Hohenzollern's II Corps which advanced against Aspern from the north. Hohenzollern found it difficult to deploy because of aggressive maneuvering by Brigadier General Marulaz's light cavalry brigade. Because Hohenzollern had only eight squadrons attached to his corp, he had insufficient mounted force to ward off Marulaz. Finally, around 3 P.M., Hohenzollern managed to reach his attack position. Erzherzog Karl had particularly enjoined his infantry to "form on the plain in battalion mass." 2

The paucity of French artillery permitted Bellegarde to do just this. He deployed his corps in two lines, with the units in the front forming battalion masses. His powerful artillery opened fire, striking particularly hard at Legrand's Division which lay exposed in the open ground southeast of Aspern. Hohenzollern's advance placed Aspern in grave peril. Answering this emergency was the Duke of Istria, Marshal Jean Baptiste Bessières who commanded the army's reserve cavalry. He was one of the army's notable eccentrics, a devout Catholic in an army of agnostics, a man who fastidiously powdered his hair in the old style while his peers relentlessly pursued the latest Parisian fashion. That he was brave went without saying; all Napoleonic marshals displayed great personal bravery. For reasons having more to do with his personality than his ability, he was one of Napoleon's favorites. Future campaigns would expose his inadequacies while on independent command. But he understood the power of a cavalry charge. When he saw Hohenzollern's column advance toward Aspern he ordered Marulaz to charge. That general's five light cavalry units -- three French chasseur a cheval regiments, and two small allied regiments, one of Baden light dragoons, the other the Hessian Garde-Chevaulegers -- numbered about 1,500 troopers. 3 Their target numbered in excess of 17,000 infantry and 50 guns. Undaunted by the odds, Marulaz's troopers advanced.

When Karl saw Marulaz surge forward, he shifted two regiments from Bellegarde's adjacent column to buttress Hohenzollern. Then he rode to the scene of the action. Encouraged by his presence, the Zach, Colloredo, Zettwitz, and Froon Infantries held firm. Close range musketry fire from their mutually supporting battalion masses coupled with effective crossfire from the brigade batteries prevented Marulaz from pushing his charges home. During the action Marulaz himself had three horses shot out from under him while his promising chief of staff fell dead at his side.

Napoleon's Countermoves

Napoleon, in turn, saw Marulaz's distress and ordered Lasalle to join the action to succor his disordered troopers. This Lasalle could not do because GdK Johannes Liechtenstein anticipated the maneuver. Liechtenstein belatedly realized that he had failed to protect Bellegarde's infantry from opposing horsemen. Accordingly, he sent nine mounted regiments, spearheaded by the O'Reilly Chevaulegers, to drive off the French light horse. This they did by engaging Lasalle frontally with four regiments and using the remaining five to charge Lasalle's flank. Still, albeit at a stiff price, the French light cavalry had forced Hohenzollern to grind to a halt and thereby purchased time for the hard pressed French infantry in Aspern.

As Karl's enveloping attack unfolded, the next French crisis occurred in the right center nearer Essling. Here the Austrian Reserve Cavalry threatened to breach fatally Napoleon's position. Again Bessières met the challenge. He maneuvered d'Espagne's cuirassier Division carefully to approach the right flank of the Hapsburg horse. His charge overthrew two lines of Austrian horse consisting of more than 1,000 cuirassiers belonging to the Erzherzog Albert and Erzherzog Franz regiments and 640 some troopers of the Knesevich Dragoons.

D'Espagne's exultant cuirassiers encountered a third line composed of the mounted regiments belonging to the Hungarian insurrection. These units were unused to war and broke before the terrifying sight of the veteran cuirassiers. The French horse found itself deep in Karl's center. But they were without supports, for there were no spare troops on the entire field. Fresh Austrian cavalry advanced against them, fire from the adjacent infantry ravaged their ranks. During this action General d'Espagne fell dead, the victim of a canister round that struck him in the face. Three of his four colonels died in this combat. The cuirassiers had to abandon a dangerously wounded Brigadier Fouler who became a Hapsburg prisoner. Marshal Bessières himself got caught up in the melee and had to discharge both his pistols and draw his sword to defend himself. In sum, four of the seven highest ranking French officers in the Division died and one was captured during this action.

Examples

These two examples were two of several times on the first day of Aspern-Essling when the self-sacrificing conduct of the French cavalry saved Napoleon's army. Some six weeks later, at Wagram, the French cavalry would have far less impact. Its losses on May 21-22, coupled with the unprecedented concentration of artillery that dominated the field at Wagram, made this so. There would be only one more field on which cavalry had close to the same tactical impact that it had had at Aspern-Essling; Borodino, the fearfully bloody battle of attrition that decided the Russian campaign in 1812.

At Borodino, as on the plains of the Marchfeld, French and French-allied heavy cavalry braved near overwhelming artillery fire to breach the Russian line. But it took too long to accompolish and was done at such a cost that the result was a drawn battle. The slaughter on that field, the ruinous loss of horses during the winter retreat, and the large number of guns and howitzers employed by all contestants during the subsequent campaigns involving continental armies thereafter relegated cavalry to a secondary importance.

Part II: The Second Day at Aspern Essling

Footnotes

1 Girault's letter is on display at the Musée de l'Emperi, Salon-de-Provence, France. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

2 The French translation of the German is "en masse par battalion, sur la demie division du centre." See MR 671, Chateau de Vincennes archives.

3 A sixth regiment, the 23d Chasseurs à Cheval, remained in reserve at this time.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 3 No. 1

© Copyright 1996 by Jean Lochet

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com