Second Day at Aspern Essling

With the French cavalry largely a spent force, during Aspern-Essling's second day it fell to the French infantry to try to win the battle. On May 22, Napoleon conceived of a direct assault against Karl's attenuated center featuring Marshal Jean Lannes' II Corps. Saint-Hilaire's veteran Division moved out first, its right flank partially protected by the French defenders in Essling. In echelon slightly behind and to Saint-Hilaire's left were Oudinot's two conscript Divisions, the men who had fought at Ebelsberg. All three Divisions advanced in a dense formation of mixed columns and squares.4

The soldiers awaiting them conducted an active defense utilizing all three arms to best advantage. During the French approach march Austrian horsemen screened the front. Suddenly they retired, thereby unmasking a formidable artillery line that pounded Lannes's columns. Bounding cannonballs furrowed gaps in the French formation. They could do nothing but close ranks and continue. The carnage became worse when they entered canister range. Hundreds of iron balls scythed through their ranks. When the French approached to within 200 yards of the enemy, the Hapsburg infantry columns closed the range and deployed. They presented a checkerboard formation with units drawn up in battalion mass. While the brigade and position batteries continued to deliver canister blasts from the flanks, the infantry waited until the French drew near and then began firing controlled battalion volleys.

"The cannonade began almost at the very moment of our advance; it was murderous because...we presented heavy masses to their artillery...We persisted in our attempts to penetrate their checkered line when the canister and musketry disordered our columns, compelling us to halt and engage in a firefight, with the disadvantage of numbers against us. Every quarter hour that we spent in this position made the disadvantage worse." 7

The assault failed with great loss of life. What was particularly important about the French casualties during the 1809 campaign against Austria was the loss of so many irreplaceable Grande Armée veterans. During Saint-Hilaires's three-hour eruption onto the Marchfeld, 130 out of 252 officers were hit including three out of every four in the "Terrible 57th" Ligne. 8 In spite of incorporating substantial numbers of conscripts into their ranks during the campaign, three regiments in Saint-Hilaire's Division -- the 3rd, 72nd, and 105th Ligne, units whose exploits began on the ridgetop of Teugen-Hausen and continued through Aspern-Essling and Wagram -- suffered so severely that following the Armistice at Znaim they had to consolidate their survivors with three battalions becoming two and a cadre returning to the regimental depots in France.

The 57th Ligne and 10th Legere fared even worse. Never again would these once superb units display exceptional battlefield performance. The number of killed and wounded cavalry leaders underscored the fact that the French mounted arm had behaved with heroic self-sacrifice. All four colonels leading Marulaz's chasseurs regiments were wounded. D'Espagne's cuirassiers lost 61 of its 109 officers. 9 Half of Lasalle's Division were casualties. The value of the Grande Armée veterans can hardly be overstated. The Russian campaign would slaughter thousands more, yet the survivors' influence could still be detected during the 1813 campaign when officers often attributed a unit's particularly valorous performance to the presence of a remaining handful.

From the late days of the Roman Empire until the Battle of Agincourt, cavalry shock action had dominated field battles. Agincourt began an era where infantry -- with bow, pike, and then musket -- was of at least coequal importance. Wagram marks the end of cavalry domination and the rise of the artillery arm. Europe's generals were slow to appreciate this. In the next great encounter between French Imperialism and German nationalism, the 1870 war, both sides organized, equipped, and dressed thousands of troopers in the Napoleonic style. Their saber and lance charges could not contend with the era's more efficient shoulder arms and artillery's improved technology. Still Europe's generals did not learn. Again in 1914 thousands more troopers went to war armed and trained in almost the same manner as d'Espagne's cuirassiers and Marulaz's chasseurs. Confronted with machineguns, modern explosive shells, and barbed wire they quickly demonstrated their uselessness.

Artillery Ascension

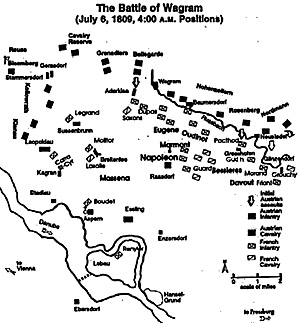

Just as Wagram is the end of the cavalry shock era, so it marks artillery's ascension toward battlefield domination. Napoleon, who of course began his career as an artillerist, appreciated better than any of his contemporaries artillery's potency. In 1796, while conducting his first campaign, Bonaparte had organized a massed battery (led by Marmont) to win the decisive battle of Castiglione. During one of his ruminations to Eugène in 1809, he told his stepson to support an attack with a massed battery of 30 to 36 guns since "nothing can resist it." 10 He added that the same guns evenly distributed along a line would fail to give the same result. The Emperor's reliance upon massed artillery reached its apogee on July 6 at Wagram when his Imperial Guard artillerists formed the core of the 112-gun Grand Battery. 11

Reflecting on the nature of combat and undoubtedly recalling those perilous two days in May 1809, Napoleon in later life said "A good infantry is without doubt the soul of the army; but, it cannot long maintain a fight against a superior artillery, it will become demoralized and then destroyed." He added, "The fate of a battle, of a state, often follows the [route] taken by the artillery." 12

Napoleon's continental adversaries had begun to comprehend artillery's value. Although they seldom managed the knack of massing guns at a decisive sector, they made up for this by the sheer number of weapons they brought to the battlefield. Karl had 452 guns at Wagram. The Russian Field Marshal Mikhail Kutusov fought the Battle of Borodino with 640 guns. On the third day of Leipzig in 1813, the Allies concentrated an incredible 1,500 artillery pieces on the field.

Clearly Napoleon's enemies had concluded that the tactical counter to French battlefield maneuverability was a crushing weight of artillery fire. Allied leaders extended their infantry masses across a wide front and buttressed the line with scores of cannon. The sheer extent of the front meant that if Napoleon tried an outflanking maneuver it would be too difficult to coordinate and take too long to complete. Alternatively, if Napoleon chose to attempt a blow against the center, the artillery guaranteed that it could not be done without such high losses that there could be no significant exploitation. 13

After Wagram, artillery's tactical domination of the battlefield negated battles of maneuver. The brilliant maneuver battles that typified Bonaparte's Italian campaign of 1796-97, the bold strokes characteristic of the glory campaigns of 1805-06 were not to be seen again. In large part this was because, "The days of Essling and Wagram had massacred the flower of the French army." 15 In their stead came grinding battles of frontal attrition. Napoleon would "win" many of these, but they were devoid of strategic significance. From Napoleon's foes' perspective, reliance upon infantry masses buttressed by a colossal artillery might not earn victory, but it ensured that a defeat would be of minimal significance.

Footnotes

4 Rovigo, who accompanied Lannes's men, attests to this formation. See Duc de Rovigo, Mémoires du Duc de Rovigo, vol. 3, (Paris, 1901), p. 121. Note from the Editor: The Source for the article is the author's Napoleon Conquers Austria.

Part I: The First Day at Aspern Essling

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Accompanying the advance by filling the gaps between the regimental columns came the artillery. Behind the guns were 20 regiments of cavalry neatly arrayed in columns to charge forward through the intervals between the massed infantry. Placing himself in front of Saint-Hilaire's Division, Lannes ordered the movement to commence. To repeated cries of "Vive l'Empereur!" the infantry set out in parade formation across the level ground that had long served as their foe's drill field.

Accompanying the advance by filling the gaps between the regimental columns came the artillery. Behind the guns were 20 regiments of cavalry neatly arrayed in columns to charge forward through the intervals between the massed infantry. Placing himself in front of Saint-Hilaire's Division, Lannes ordered the movement to commence. To repeated cries of "Vive l'Empereur!" the infantry set out in parade formation across the level ground that had long served as their foe's drill field.

Perhaps more experienced attackers, men trained at the famous camps of instruction at Boulogne, could have opened their ranks to limit the artillery's ravages. 5 But two-thirds of the attacking force were conscripts, and they lacked the capacity to perform complex maneuvers when under close range fire. So it became a battle of attrition and of will. The Duke of Rovigo 6 describes the scene:

Perhaps more experienced attackers, men trained at the famous camps of instruction at Boulogne, could have opened their ranks to limit the artillery's ravages. 5 But two-thirds of the attacking force were conscripts, and they lacked the capacity to perform complex maneuvers when under close range fire. So it became a battle of attrition and of will. The Duke of Rovigo 6 describes the scene:

Irreplaceable Losses

Irreplaceable Losses

During the Battle of Wagram, more Frenchmen were struck by enemy fire on a single day than on any other field during the Napoleonic Wars. It would take the Battle of the Somme 107 years later to surpass their loss rate. 14 Thus, Wagram revealed that a battle won by a frontal breakthrough would be so costly that there could be no pursuit. Subsequent campaigns would verify this lesson. In time Napoleon's adversaries appreciated this. After Napoleon defeated the Prussians at Ligny in 1815, a Prussian officer who was familiar with the Emperor's war machine informed Wellington that the French would not pursue early the next morning because they required time to rest and refit.

During the Battle of Wagram, more Frenchmen were struck by enemy fire on a single day than on any other field during the Napoleonic Wars. It would take the Battle of the Somme 107 years later to surpass their loss rate. 14 Thus, Wagram revealed that a battle won by a frontal breakthrough would be so costly that there could be no pursuit. Subsequent campaigns would verify this lesson. In time Napoleon's adversaries appreciated this. After Napoleon defeated the Prussians at Ligny in 1815, a Prussian officer who was familiar with the Emperor's war machine informed Wellington that the French would not pursue early the next morning because they required time to rest and refit.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 This is the view of Savary, who accompanied the assault. See Saski, vol. 3, p. 252. (Saski C.G.L. La campagne de 1809, Paris, 1899-1902.)

8 Rovigo, pp. 121-122.

9 Regimental officer losses: 3d, 27/51; 57th, 31/41; 72d, 25/42; 105th, 23/52; 10th Leg., 24/66. Saski, vol. 3, p. 398; and Martinien (Martinien, Aristide Tableaux par corps et par batailles des officiers tués et bléssés pendant les guerres de l'Empire, Paris 1899.

10 Napoleon to Eugène, June 7, in Picard, Préceptes et Jugements, p. 39.

11 Many guns were remanned by Grenadiers and Chasseurs of the Imperial Guard, which were also trained as artillerists.

12 Picard, pp. 30-31.

13 Bautzen is an example of the difficulty of outflanking an artillery-studded defensive line. Recall also that Napoleon rejected Davout's idea to try to outflank the Borodino position because he feared it would take too long.

14 Borodino's total of 33,000, most of whom were killed and wounded, comes close. The three days at Leipzig claimed more than 70,000 men, many of whom were captured. Waterloo cost perhaps 40,000 but again, many were captured.

15 General Koch, Mémoires de Masséna, vol. 6 (Paris, 1850), p. 332.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 3 No. 1

© Copyright 1996 by Jean Lochet

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com