The subject of British skirmishing has been covered only once in E, E & L , by Dick Ponsini (whom I contact now to comment on the above article by John Koontz). Dick has, for a long time, told us during our wargames, that the British light infantry was fighting almost exclusively in "extended order" and not as true (i.e. dispersed) skirmishers.

I don't intend to cover that subject completely in a few lines but simply to present some of the data I have at the present time just a base for a further discussion including as such involvement from oar readers (It's the reason of the Readers' Forum!)

In my opinion, the British practice of having more skirmishers on the battlefield is one of the keys, if not the basic key, to the British victories against the French and NOT the superiority of the line against the column.

I fully realize that I am presenting here an idea that is against accepted principles ... Yet, if one considers the data available...

Firstly, a British skirmishing line was, apparently, not very different, an far as frontage is concern, from a standard two-deep line. Apparently, most of the time, the British skirmisher line was not widely-spaced (see below) and the only difference with a standard line was (only) the spacing between the files!

So, the French, who were used to such more open skirmisher lines mistaken the British skirmisher line for lines. The following is taken from Philip Haythornwaith's Weapons and Equipment of the Napoleonic Wars. Blandorf Press, 1979, page 11:

- Skirmishing, in which the light infantryman operated as an individual, required a

degree of intelligence above that of the automatic drill of the line. In skirmish order the

men were rarely widely spaced (in British service, "open order" signified two feet

between files, 'extended order' two paces), though in combat frequently adopted a much

more 'individual' role. Light troops generally worked in pairs, so that one would always

have a loaded musket, and all movements executed in 'quick time', 'each firing as quick as

he can, consistent with loading properly. Two basic methods of movement were practised:

either formed in two lines, the rear rank advancing directly through the gaps in the front

rank; or, when 'covering' each other,

'. . . as soon as the front rank man has fired, he is to slip to the left of the rear man, who will make a short pace forward, and put himself in the other's place, whom he is to protect while loading. When the first man returns his ramrod, he will give his comrade the word ready, after which, and not before, he may fire, and immediately change places as before.'

When advancing the same drill was used, save that the rear man would move around his comrade and six paces in front; when retiring the front, man would do likewise but withdraw twelve paces.

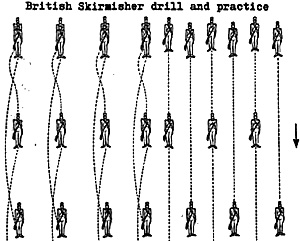

The above drill is shown in the following sketch made from the same source page 14.

The above drill is shown in the following sketch made from the same source page 14.

Secondly, the British true line of battle, the famous red thin line was usually sheltered behind the reverse slope or laying down like at Waterloo. Note here that British troops were the only ones capable of laying down to wait for the enemy, something hard to understand in our time. So, it easy to understand that the French not seeing the true line of battle could mistake the skirmisher line (as we have seen above not very different from a battle line) for the battle line.

Thirdly, the British skirmisher-line or lines were given way to the French columns. (It was never the task of skiemishers to stop an attack or to melee the enemy) So, the French did not see the need to deploy ... Remember the true battle line was not visible yet!

Archibald Frank Becke in Introduction to the History of Tactics: 1740-1905, London, 1909, resumes the above situation very well:

- Wellington adopted the tactical defensive almost invariably, and took up a poisition 100 yards or

more behind the crest of a plateau, covered his front with a thick chain of skirmishers and some light guns;

whilst his other troops, deployed in a two-deep line, awaited the assaulting French, reserving their fire till the foe reached decisive range, finally pouring in a valley and then charging. In many cases the French had literally, owing to the skill Wellington showed in taking up a position, to take the bull by the horns.

Hence, an reading the crest of the plateau they were often taken by surpise, and ere they could deploy were attacked by the unshaken British line, which mangled the front of the French formation with fire as it strove to struggle out into line, and then advanced promptly with the bayonet to complete the decision. The French, of course, were using columns as formations of Maneuvre, and 'had missed the psychological moment when they should have, and could have still, deployed, and thus were caught at a disadvantage. The British two-deep line naturally outflanked the French (if the latter failed to accomplish the deployment), enfiladed them, and crushed them with fire. And that the French in the Iberian peninsula were often caught in the column formation ere they deployed is undisputed.

As stated by John Koontz, in many reports), the French reported that they had broken the British line in several occasions.

They had simply mistaken for the line of battle ... Certainly the French learned from their mistakes... A battle of Spain became proverbial! The best instance took place at Quatres-Bras, in 1815, when, at the beginning of the battle, around one thirty in the afternoon, Marshal Ney said to General Reille: "There is hardly anyone in the Bassus wood, take it immediately."

Reille replied: "This could be a battle of Spain, in which the British will show themselves when absolutely necessary. It would be wise to wait for all all troops to be here."

Ney, impatiently, replied: "Not so! The voltigeurs company will be sufficient!".

Nevertheless Reille's answer certainly shook Ney since he awaited the arrival of Bachelu's second brigade and Foy's division.

The above was taken from Houssaye's 1815 page 193 and is reproduced below:

- Vers une houre et demie, Reille, qui marchait avec la tete de colonne de la division Bachelu, rejoignit Ney. "Il n'y a presque personne dans le bois de Bossu, dit Is marechal, il faut enlever ca tout de suite." Reille etait ce jour-la d'humeur peu entreprenante; il repondit . . "Ce pourrait bien etre une bataille d'Espagne, ou les Anglais se montreront seulement quand il sera temps. Il est prudent d'attendre pour attaquer que toutes nos troupes soient massees ici." Ney impatiente repliqua :"Aliens donc! Il suffira des scules compagnies de voltigeurs! ," Neanmoins la remarque de Reille l'avail fait reflechir; il differa l'attaque jusqu'a l'arrivee de la seconde brigade de Bachelu et de la division Foy'.

We all know that if Ney had launched his attack at that point, hardly any troops were in the Bessus wood and he would have certainly carried Quatre-Bras, changing completely the outcome of that battle, but that is another story.

More Readers' Forum: British Skirmishers

More Readers' Forum: Napoleponic Rally Formations

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 48

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1980 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com