In October 1794, General Canclaux commanding the

main Republican force in the West, i.e. involved in the

Vendee, estimated the nominal strength of the three armies

there as 136,000, out of which after deduction of the

garrisons, left some 50,000 men to be employed as active

forces in the field. In contrast, the two Republican armies

one conquering Holland and the other advancing on the

Rhine had respectively some 67,000 and I 11,000. In 1796,

when the Vendee was finally pacified, Hoche's army of the

West was about 117,000 strong, about 45,000 of which were

sent as reinforcements to the frontiers. In addition, the toll

of the struggle between the "Blues" (Republicans) and the

"Whites" (the Vendeans) was extremely heavy and caused

an estimated 600,000 casualties. Indeed a very heavy drain

since, in 1789, France had a population of about 26 millions.

The theater of war was not limited to the actual

department of the Vendee which is located in the West of

France and part of the province of Poitou (see Map). As it

will be seen the conflict area extended much further to

Poitou, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, Touraine and even to

Normandy. Like most of France in 1789, the Vendee was

largely agricultural. It was somewhat of an economically

backward region with few large towns, and somewhat

isolated from the rest of France by its poor roads.

It may come to a surprise that the Revolution of 1789

was received in the Vendee with few disturbances. The

majority of the Vendean peasants were even favorable to

the new revolutionary government. The Vendean gentry

was not particularly close to the peasants, nor religious

[2]

in a province highly pious, but a rather ignorant bunch

trying to cling to their privileges. Of course the great

majority of the nobles were Royalist and only very few

joined the Revolution. From the beginning they tried to

reverse the course of events. Consequently, in 1789, like in

the rest of France, a certain rivalry existed between the

peasants and the nobles but in Vendee the peasantry

preserved a certain respect for the old families and no

excesses were committed.

In the Vendee country, the peasants were fervently

religious and were very close to the sincere and high faith of

the local country priests which were sympathetic to

democratic instincts. Hence, when the Revolution started,

the later welcomed the coming of egalite proclaimed by the

Convention as the fulfillment of the scriptures. In addition,

the elimination of the feudal taxes was a welcomed relief for

the Vendean peasants. For them, the real leader to follow

was the local priest as the local noble did not yet inspire

their trust or respect. If the local priests had remained on the

side of the Revolution, the revolt of the Vendee would not

have taken place.

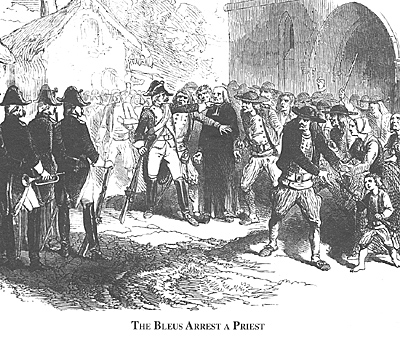

The rising of the west of France in 1793 was caused

mainly by two measures voted by the Convention. The first

one was the attempt to implement the Civilian Constitution

of the Clergy which had been pushed by Camus. In this

document, Camus, an uncompromising and strict Jansenist,

decided to reform the discipline of the Catholic church. He

did not realize that the changes to be brought up were a

fuse on a powder keg!. The reforms required the priests to

take an oath to the new constitution and were equated to

the imperilment of religious freedom. The immediate

consequences were that the local priests deserted the

Revolution and the local people supported the priests who

refused to take the oath. The arrest of the local priests who

refused to take the oath and other provocations did the rest

and resulted in local open hostility and mass

demonstrations. The second measure that broke the camel's

back was the introduction by the Convention of the military

laws of February 20 and 24, 1793 calling to arms an

additional levy of 300,000 men.

The full fledged insurrection did not start

immediately. It should be realized that the armed resistance

to the Convention was not limited to the west. All over

France, the royalist party was stronger that it is generally

realized. Two large cities Toulon and Lyon were already in

open rebellion and had to be reduced by

regular sieges. In addition, Brittany was already ablaze by

the action of the Chouans.

[3]

Of course, as the nobles of the West were royalists,

like everywhere else, they had started to plot against the

Revolution. In the Vendee that resulted in several attempts

to start an open revolt. As early as June 1791 a conspiracy,

in which most of the local nobles took part and met at the

castle of the Proutiere, had for objective the taking of the

city of Les Sables d'Olones. The local government was

informed in time and sent the National Guard that burned

the castle and made a number of arrests. The prisoners were

soon released by a general amnesty of the Convention. But

the nobles did not give up and continued to work up the

local peasants.

From June 1791 to the end of August 1792, no less

than nine attempts to insurrection took place. In January

1793, the judgment of Louis the XVIth did not help the

situation. If the country folks had been pro-revolutionary

and for reforms that did not mean they were against the

King.

They simply were, like most, against the outdated

privileges and the overbearing taxes. In fact they were

deeply royalist. Consequently, worked on by the local

priests and the gentry they became increasingly hostile to

the Convention.

As a general rule, the people of large town and cities

where the bourgeois were numerous

[4] were more

progovernment, but the country folks less so. It was in the

west that the rivalry between the cities and towns and the

country was the greatest. Consequently, these larger towns

and cities were pro-government strongholds and never rose

against the Republic.

La Vendee Napoleonic French Rebellion 1793

I could not let 1993 go by without covering the

Vendee [1] rising as

two hundred years ago, in March 1793 to be exact, the

tragic, confused slaughter called the war of La Vendee

started. Like all civil wars, it was to mark France for years to

come and by its massacres put another black mark on the

already discredited French Revolution. The Vendee

insurrection is too important of consequences to be ignored

by anyone interested in the wars of the French Revolution

and of the Empire, as the struggle heavily affected the

armies facing the enemy on the frontiers of France. The war

in La Vendee took a heavy share on the French resources at

a time when the Republic needed all the available forces to

check the invasion by the Allies.

I could not let 1993 go by without covering the

Vendee [1] rising as

two hundred years ago, in March 1793 to be exact, the

tragic, confused slaughter called the war of La Vendee

started. Like all civil wars, it was to mark France for years to

come and by its massacres put another black mark on the

already discredited French Revolution. The Vendee

insurrection is too important of consequences to be ignored

by anyone interested in the wars of the French Revolution

and of the Empire, as the struggle heavily affected the

armies facing the enemy on the frontiers of France. The war

in La Vendee took a heavy share on the French resources at

a time when the Republic needed all the available forces to

check the invasion by the Allies.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 3

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com