The Company and the Evolution of the Regiment

At the start of the civil war the regiment as a unit of military organisation was still somewhat 'new-fangled'. John Keegan [16] goes so far as to say:

Although the term had been used as early as 1544, its application tended to be rather haphazard. Henry VIIIs three battles or 'wards' in France in 1544 had been called regiments,

and in 1585 the entire expeditionary force to the Netherlands had also been called a regiment. [17]

By 1588 the 25 wards of the City of London supported 4 regiments (imaginatively called the North, South, East and West Regiments), each of 10 companies, and commanded by a Colonel (a term with similarly loose application). Apparently, however, and significantly, although the four

regiments were formed, none had a colonel. By 1599 the organisation into companies and regiments had been abandoned; instead the 25 wards of London furnished 15 companies of militia. This points to the somewhat secondary nature of the regiment as a formation. At this time a regiment was, strictly speaking, simply an amalgamation of companies - the exact number depending on availability and circumstances - and it was to the company that loyalty seemed to be owed.

The civil wars occur at a time of transition when military practice was at a stage of development from the mediaeval to the modern. Even as late as the start of the civil wars, military organisation still had some mediaeval elements about 108 - the raising of levies by local magnates - and the company was to some extent simply an extension of this. Although the infantry later firmly embraced regimental organisation, it is noteworthy that the cavalry maintained a tradition of (practically) independent companies (troops) well into the civil war itself. Even in London, which by 1616 had formally re-established its four infantry regiments, the companies still seem to have been the primary focus. Each was recruited from a specific area, and although grouped into one of the regiments, the resulting cohesion nevertheless

was focused on the company rather than the regiment, highlighting the company as a social unit:

Indirect evidence of the importance of the company is

furnished by a set of London Trained Band colours described

in Surveys of the Armed and Trayned Companies in

London for Armada year 1588 and also 1599.

[19]

The descriptions are pseudo-heraldic in tone, and have

caused some confusion amongst those trying to reconstruct

them. [20] For present

purposes, however, it does not matter precisely what the flags

looked like. The descriptions are sufficient to enable the

conclusion that these flags were not organised into a system,

as defined earlier, but comprised sets and then only in virtue

of the fact that the companies were grouped into regiments.

One example should serve to illustrate the point. The flags of

the London North Regiment are, briefly, described as follows:

[21]

The interesting feature of this set of descriptions,

apart from the evident lack of system, is that some of the

companies appear to have carried similar (if not identical)

designs. Quite clearly the flags were those of the individual

companies, not of the regiment. In other words the company

served as the focus of organisational attention.

This emphasis on the company seemed to persist even

after the Trained Bands were reorganised into 6 'coloured'

regiments after February 1642 - the Colonels appointed to

command the regiments were aldermen (i.e. political

appointees) with no military experience, and responsibility

therefore naturally fell on the company captains (including the

staff officers - the lieutenant colonel and major).

Nevertheless, military practice in England was clearly

influenced by continental practice, especially with the return

of British professional soldiers from the Thirty Years War.

That the London Trained Bands and Auxiliaries re-organised

themselves into 'coloured' regiments seems to be evidence for

this. It is also evidence to support the claim that the London

Militia was able to 'keep up with fashion'.

Regiments with colour names (such as Red Regiment)

were very fashionable among the Protestant powers in

Continental Europe at the time. Richard Brzezinski

[22] explains that they

were first established by Count Mansfield in 1620 - 21 as

mercenary regiments for the German Protestants. The Swedes

established regiments with the same names (Red, Blue, Yellow

and Green Regiments) in 1625 - 27, and Gustavus Adolphus

increased their number in 1629 - 30. It is hard to imagine that

this did not influence the London Militia's choice of name for

their own regiments - particularly in view of their self image as

warriors in a Protestant cause, and the near deification of

Gustavus Adolphus as a Protestant hero at the time.

But there were undoubtedly other influences as well.

Continental regiments, for example, tended not to distinguish

their companies in the same systematic manner as the London

Trained Bands, that is by the systematic increase in the

numbers of a unifying device. Richard Brzezinski illustrates

some colours from Swedish regiments, and it seems that while

there may have been common patterns of design, these were

not systematically related to one another within regimental

sets. Indeed, as Dave Ryan remarked recently, it is quite

possible that the systematic nature of the London Trained Band colours may have been a uniquely English development. Keith Roberts argues that English military theory was

firmly based on (or largely influenced by) the Dutch style.

Even so, the theory allowed (or failed to prevent)

considerable 'flexibility' of interpretation, depending on

circumstances and, one supposes, the preferences of officers:

'[A]s a result the organisation of regiments varied somewhat.'

Roberts goes on to make the point that, although

heavily influenced by Dutch theory, English military

practitioners also experimented with their own innovations,

often responding directly to prevailing practical

circumstances. Furthermore, and this is a point worth

emphasising:

Richard Symonds provides some clear evidence to

support this. In his Notebook (Harl. Ms 986) he records

flags from the Royalist Oxford Army in 1644. Many of the

regiments have only a handful of colours, certainly fewer than

the notional 10 companies of an average regiment, and the

rest contain mixed sets - colours of different designs. In other

words, the evidence tends to favour diversity of practice, and

diversity of arrangements, rather than uniformity.

Much of the discussion about systems of

differentiation in infantry colours seems to rest on an

expectation of uniformity - that the same practices must have

been adopted univenially, at least within the same army.

It is also worth remembering that Continental practice

may have had an influence in this respect as well. If, as Dave

Ryan suggests, the systematic differentiation of companies

by their flags was a uniquely English invention, it is also

possible that different, more Continental, practices may also

have been used conjointly with the English pattern.

In terms of the present discussion, however, my

contention is that the doctrine that companies within English

regiments were in general systematically differentiated

one from another by the designs of their flags, has been

extrapolated too far. Furthermore, this doctrine is

inappropriately generalised from the relatively simple

geometric designs of the London Trained Band colours (after

1642) to other designs, notably stripes and gyrons.

It has been suggested that regiments carrying striped

flags, may have differentiated their companies simply by

increasing the number of stripes. I have four objections to this

contention. First there is no evidence whatsoever that there

was such a thing as a striped system. There are, of course,

examples of striped flags, but these on the whole tend to be

single isolated examples. Second, as already noted, it is quite

possible that in a regiment bearing striped colours, the

companies may have been distinguished, if at all, by the colour

of the stripes, not the number. Third, from what evidence

there is it is quite possible that isolated companies may have

carried striped flags, but not necessarily whole regiments.

Even had regiments carried several such flags, it is quite

possible that they had only one or two in any case. In other

words, the Isolated examples of striped flags (as shown, for

example, in the Turmile manuscript ff 135, 147 & 148 and

Fitzpayne-Fisher, illustration 44) may have been a true

representation of what was carried - no more, no less.

That is, examples simply of striped flags, but not

representatives of striped systems. Finally, the one feature of

stripes which is inescapable is that as the number increases, it

becomes more difficult to distinguish one design from

another. How could one, at a glance, tell the difference

between, say, six and seven stripes on a field, especially if the

flag is flying?

Furthermore, local practices were often adopted in the face of regulations - the

adoption of the 'Battleflag' among Confederate regiments is a good example. Closer to

our own time, the Second World War and the Vietnam at, to pick two major conflicts at

random, demonstrate the extent to which what is written in regulations and what is

adopted in practice often bear little relation to one other. It is surprising, therefore,

that the expectation of uniformity in practice during the English Civil Wars is so

persistent. Even had the authorities wanted to establish consistent practice across the

armies, it is highly unlikely they would have had the ability to enforce it.

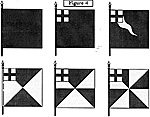

In the case of gyrons, it has been suggested that the

companies were distinguished one from another by increasing

the number of divisions in the Field (see Figure 4). This is, of

course, quite plausible. But it is based on only one example -

and one that is not altogether 'pure' at that. Symonds

recorded the flags of Apsley's Regiment at Aldbourne Chase

on 10th April 1644.

He showed six flags in what has been taken to be 'the'

gyronny system. Unfortunately for this view the Major's

colour (with the wavy pile) appears to be out of colour

sequence. Whereas all the other colours are clearly black and

white, this flag has some cryptic notes next to it suggesting it

may be otherwise. In particular there is an indistinct g

under the flag, which Symonds uses to indicate red, and there

is also an o next to the wavy pile, suggesting yellow.

Thus, the major's flag in this 'sequence may, in point of fact,

have been red and yellow. In other words not part of the same

sequence at all.

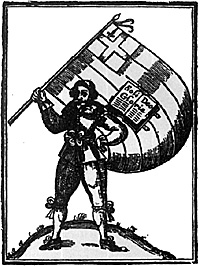

A different version of a gyronny system, from the 16th

century, has been illustrated by Ian Heath (p 63). This was

taken from a picture map of the Earl of Essex's Army in

Ireland in 1599 (see Figure 5). What is most striking about

this set of flags is that it combines stripes and gyrons. There

are also some unusual patterns within the set - notably the

design with the large pile extending diagonally from the

hoist into the fly. And it is noteworthy that with the exception

of one flag all the others are parti-coloured into two or

four divisions of the field.

The set of flags in figure 5 raises interesting

possibilities. First these flags are similar in some ways to

Stuart Reid's speculative gyron system (published in

English Civil War Notes & Queries) in which he

suggests, inter alia, one flag in the sequence may have been

divided simply into two halves.

[28]

Second, the similarity of some of these designs to one

another is suggestive of the two flags recorded for the Duke

of York's regiment by Richard Symonds (Hart ms 986, f82v).

Symonds notes that this regiment had 'but 2 ensignes at ye

slighting of Reading'. Moreover, both flags appear to be

identical - perhaps they really were, or perhaps their colours

were rotated as in some of the flags in figure 5.

Finally, while it has generally been assumed that

descriptions of parti-coloured flags referred to stripes, this set

suggests other possibilities. A good example of this is the

following from 1639:

There is nothing in this description to suggest stripes,

or indeed any other kind of design. In similar vein, the

following has also been interpreted as a description of striped

flags:

In both cases, however, it is quite possible that the

designs were other than striped, which somewhat undermines

the contention that early Trained Band flags were inevitably

stripey. On the other hand, it should be pointed out that the

last description is at least faintly reminiscent of an illustration,

apparently of a London colour (again!), from a 1641

broadsheet (Thomason Tracts, E669, F4 (32). See Figure 6).

None of this, of course, means that there were no

striped systems. Nor that stripes and gyrons were frequently

mixed. But my contention is that trying to reconstruct whole

sets of flags from isolated examples is a fruitless undertaking,

because practice was very variable.

So, what conclusions can be drawn from this? First, it

is clear that our ideas about English infantry flags used

beyond the confines of London have been disproportionately

influenced by London examples. Perhaps this is inevitable,

given the importance of London as the country's capital. But

we need to be cautious about taking London patterns as the

basis for practice elsewhere in the country. That said, neither

should we err too far in the opposite direction. Clearly there

was communication [31]

throughout the country, and practices (and fashions) will

have become known about sooner or later - although whether

they were adopted is another matter, and largely dependent

on prevailing local circumstances.

As to systems using stripes or gyrons as their

differentiating devices, again the evidence is patchy. From

16th century examples it is possible to conclude that there

may well have been no such thing as a striped system,

simply sets of flags with striped designs. And similarly so

with gyrons. The flags recorded for Apsley's regiment in 1644

give some indication that gyrons may have been used as part

of a systematic ordering of companies, but again the example

from the sixteenth century illustrates an entirely different

pattern from that exemplified by Apsley's colours, suggesting,

perhaps, that there was not a gyronny system, but possibly

several (including those that combined stripes and gyrons

into one set).

Taking into account other considerations, it is clear

that the organisation of regiments varied somewhat during the

civil war. It is also clear that regimental strengths varied

considerably, especially as the war progressed and, at least on

the Royalist side, attrition took its toll and field strengths

began to dwindle. Again with particular reference to the

Royalist experience, regiments were often strengthened with

soldiers from other regiments, which makes the possibility of

mixed stands of colours more likely - as perhaps illustrated by

Symonds in his Notebook. But, further than this,

sixteenth century practice seems to suggest that mixed stands

of colours were actually quite common, and that at that time

emphasis lay with the company rather than the regiment. On

the assumption that sixteenth century

practice may have been continued into the seventeenth

century it is therefore possible that mixed stands of colours

may also have been used during the civil wars, not because

of negative circumstances but as ordinary practice. Of course

this is speculative, but not without some evidence in support.

Whether regiments of the main English field armies, of

both sides, generally adopted the practice of systematic

differentiation of companies by their flags is moot. There is

evidence that some such practice wad used outside London,

but it is patchy and inconclusive. Certainly nothing should be

concluded from isolated examples of flags - these may or may

not have been part of a system. That is, simply

because an isolated flag seems to have a similar design to

other flags that are known to have been part of a system

means relatively little. Such isolated flags may have been just

that - isolated examples.

In the end, perhaps it is unreasonable to expect that

seventeenth century practice was more uniform than is even

possible in the twentieth century. Maybe it is more

reasonable to suppose that seventeenth century people did

what twentieth century people do - use what's to hand, and

improvise the rest. In the matter of flags, the evidence

suggests diversity of practice, not uniformity. And that, to

me, seems eminently reasonable - and very human.

When faced with having to make a choice, and having

little to go on, pragmatism seems to be the best option. The

patterns offered by the London Trained Bands are a good bet

if you want to create a systematic set of colours - nothing I

have said in the article precludes their use if you want to go

along with them. On the other hand you could, if you wanted

to, create an excitingly diverse set of flags - and I don't think

you would go far wrong. But it is worth bearing in mind that

as far as we can tell (which isn't very far) the New Model

Army may well have adopted the Venn pattern - for which

there is some oblique evidence (together with a lot of

imaginative hopefulness). For Royalist regiments in the later

civil war mixed (and small) sets seem to be more normal. Just

one point though - please don't use giant cavalry cornets for

infantry regiments, which were an unhappy feature of early re-

enactment regiments - when no-one knew any better and

which appear regretably to be creeping back into fashion.

1: Contemporary sources

Elton, R. Compleat Body of the Art Military. (1650).

2: Modern Sources

Brooke-Little, J. P. (1973) An Heraldic Alphabet. London: Macdonald.

I would like to thank Dave Ryan, who kept nagging me to

write this article, and without whose generous assistance I

would certainly not have had the resources I currently have at

my disposal to generate the necessary information. Any

peculiarities of logic, wild and unfounded speculations and

errors of fact are, of course, my fault - except the ones Dave

encouraged me in. Thanks also to All and Martha who read

earlier drafts of the article, even though they generally regard

the subject matter as being less interesting than used teabags.

Ede-Borrett, on the other hand, interprets the designs as horizontal stripes, which

is more in keeping with Tudor patterns (Fde-Borrett, 1997: 36 - 37). This all hinges on

the significance of the term 'pane' in the original source. Gush says that it is not an

heraldic term, and that therefore it is reasonably safe to understand it as referring to

stripes. Unfortunately he is not correct. Pane is a term sometimes used in heraldry to

refer to the small rectangles of colour which form the chequy and compony patterns

(Brooke-Little, 1973: 155), which means that these flags could very easily have been

checked. To be fair to Gush, however, he does consider this as a possibility (p 12).

More Systems

at its birth in the seventeenth century the regiment was not merely a new but a revolutionary constituent of European life. (p 12)

The system of recruiting men from a particular

area to form companies of the Trained Bandd was intended as a military measure to endure a quick muster in time of emergency but also led to the formation of strong loyalties, in the companies between the Trained Band soldiers and their officers, most of whom

also came from the dame area. The local association., were

orimally formed to improve military training but as they

were formed of men from the dame didtrict they also

developed a social connection amongst their members

(Roberts, 1987: 8)

Cornehill Coy. Black and white waves Broadstreete Coy. Black and white waves Collman Streete Coy. Blue and yellow waves Bassingshaw Coy. Orange-tawney and white waves Criplegate Coy. (1) Black and white waves Criplegate Coy. (2) Red and white waves Criplegate Coy. (3) Green and white panes St. Martin le Grand Coy. Black and white panes Aldersgate Coy. Green and yellow panes Cheapsyde Coy. Black and white panes

[23, 24]

[25]

In many respects the theory went by the board anyway as

some colonels, particularly on the Royalist side, never managed to

recruit a full regiment. In other regiments, however, the colonel's local

influence remained powerful and he was able to raise extra companies

or incorporate others from disbanded units into his own regiment.

[26]System and Uniformity

[27]But the

balance of probabilities suggests that this is highly unlikely,

and the circumstantial evidence suggests that it was not

attained even if people tried to achieve it (which is doubtful).

Stripes and Gyrons

[27] This expectation has

always puzzled me - particularly in the light of evidence from later, more industrialised,

conflicts. There is, for example, an abundance of photographic and documentary

evidence from the American Civil War which demonstrates, beyond dispute, that

despite regulations and the means to produce materiel to uniform standards, equipment

and practice still varied considerably. No-one has yet satisfactorily explained, for

example, why so many Confederate generals wore the uniforms of Confederate colonels.

And, despite clear regulations about uniforms, those actually worn by the combatants -

of both sides - were remarkable for their lack of conformity to regulation rather than

otherwise.

At right: Col. Apsley's Regiment of Foot The 3rd Regiment of Foot at the Aldbourne Chase Muster, Wednesday 10th April 1644, Source: Symands Notebook, Harl. Ms f79v.

At right: Col. Apsley's Regiment of Foot The 3rd Regiment of Foot at the Aldbourne Chase Muster, Wednesday 10th April 1644, Source: Symands Notebook, Harl. Ms f79v.

ECW Col. Apsley's Regiment of Foot Flags: Large (27K)

At right: Earl of Essex Army, Ireland 1599, Source: Ian Heath, Armies of the 16th Century.

At right: Earl of Essex Army, Ireland 1599, Source: Ian Heath, Armies of the 16th Century.

ECW Earl of Essex Army Flags: Large (49K)

"The King went forth [from Newcastle- upon - Tyne] to see 3

regiments of foote and a troupe of horse. The first regiment was the

Earl of Essex, devided into two squadrons and consisted 1500 men.

The 2 wad the Earl of Newport, devided likewise, and consisted 1500

men. The Collers of the first was orringe tawney and white. The 2

was green and white".(HMC Rutland Papers )

[29]

It is agreed that the Inhabitants of this Burrough

shal be divided into twoe Companies for ye Muster ... And

both to have the Towne Cullors of white and greene with

some little distinction to be knowen one from the other ...

(The Old Ligger Book, 21st June 1633. Newport mss. 45/2

f62V) [30]

Concluding Comments

Note for War Gamers and Re-enactors

Note for War Gamers and Re-enactorsReferences and Bibliography

Fitzpayne-Fisher, British Library Hari. Mss 1460.

Good News forall true hearted subjects. 1641. ThomasonTracts F669 f4 (32)

HMC Rutland Papers

Levert, W. The Ensignes of the Regiments of the Rebellious Citty of

London Both of Trayned Bands and Auxiliaries. September 1643 National Army

Museum Ms 6807-53.

Lucas, J. London in Armes Displayed. 1647. British Library Add. Mss. 14308.

Order to Alexander Venner, Public Records Office, State Papers, SP28/3/77.

Symonds, R. Notebook. British Library Hari. Mss 986.

Symonds, R. Diary of the Marches of the Royal Army. British Library, Hari. Mss.,

939, 911, 944; Add. Mss. 17062. Printed by the Camden Society 1859. The Old

Ligger Book. Newport Mss. 45/2

Turmile, J. The Colours or standards and armorial bearings of certain officers in

the parliament army 1642 and a list of the colours taken by the Earl of Essex general

of the parliament army at Udgehill oct. 1642 and also of the colours taken by Sir

Thomas Fairfax General of the parliament Army at Knaseby June 14 1645. Dr. Williams

Library, Ms Modern Folio 7. (Photographic copy at National Army Museum, ref. NP

7373).

Venn, T Military Observations or the Tacticke put into Practice. (1672).

Brzezinski, R. (1991) The Army ofGustavus Adolphus - 1: Infantry. London: Osprey.

Dillon, H. A. (1890) 'On a MS list of officers of the London Trained Bands in

1643'. Archaeologia, 52, 1, 129 - 144.

Ede-Borrett, S. (Undated) 'The colours of Prince Rupert's Blew Regiment of

Foot'. English Civil War Notes & Queries, 14, 5 - 7.

Ede-Borrett, S. (1997) Ensignes of the English Civil Wars. Pontefract: Gosling Press.

Firth, C. H. (1962) Cromwell's Army. London: Methuen.

Firth, C. H., & Davies, G. (1940) A Regimental History of Cromwell's Army.

Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Gush, G. (1976) 'The Trained Bands of London & their Standards in the reign of

Elizabeth I'. Arquebusier: The Journal of the Pike and Shot Society, IV, I (Jan/Feb

1976) 10 - 14.

Heath, I. (1997) Armies of the Sixteenth Century. St. Peter Port: Foundry Books.

Keegan, J. (1993) A History of Warfare. London: Hutchinson.

Leslie, J. (1925) 'A survey, or muster, of the Armed and Trayned Companies in

London, 1588 and 1599'. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, IV, 16,62.

Matthews, J. (Undated) 'The colours of Prince Rupert's Regiment of Foot: A

reconstruction'. English Civil War Notes & Queries, 17, 6.

Peachey, S., & Prince, L. (1991) ECW Flags & Colours: I - The English Foot.

Leigh-on-Sea: Partizan Press.

Peachey, S., & Turton, A. (1987) Old Robin's Foot. Leigh-on-Sea: Partizan Press.

Roberts, K. (1987) London & Liberty: Ensigns of the London Trained Bands. Leigh-on-Sea: Partizan Press.

Roberts, K. (1989) Soldiers of the English Civil War (1): Infantry. London: Osprey.

Reid, S. (Undated) '1639 Snippets'. English Civil War Notes & Queries, 9, 19.

Reid, S. (Undated) 'Colours and Cornets'. English Civil War Notes & Queries, 16, 11.

Acknowledgements

Notes

[16]

John Keegan, A History of Warfare.

[17]Ian Heath Armies.

[18] Interestingly the term 'colours', used

to refer to military flags, seems also to reflect the transition from mediaeval to modern.

Although from the 1530s heraldry had ceased to have the battlefield precedence it

once had, ordinances issued in 1562 demonstrated that military flags -ere still

embedded within heraldic practice - 100 men expected to serve under a standard, and

50 under a pennon or guidon. Nonheraldic coloured flags seem to have developed

with the advent of non armigerous captains, who, of course, had no armorial devices

to display, hence the collective term 'colours' (Ian Heath op cit., p 61).

[19] Heath, Armies, p 62.

See also Gush (1976), Leslie (1925) and Fde-Borrett (1997).

[20] 1 am not trying to be

rude to other commentators here. The descriptions are, in some respects, 'potty', bearing

all the hallmarks of someone who wanted to sound technical, but without the requisite

knowledge. The flags have generally been interpreted as striped in appearance, which is

reasonable given the prevalence of striped flags during the sixteenth century. But, as is

so often the case, there is room for interpretation. Leslie (1925) interprets the designs as

bearing a close resemblance to heraldic banners. Gush draws from sixteenth and

seventeenth century models to produce patterns more closely in line with common

practice in these periods. What is surprising, however, is that he portrays the stripes as

vertical (Gush, 1976: 13 - 14).

[21] These descriptions are taken from Gush (1976), page 12. It is also instructive to look at the whole set of descriptions that Gush reports.

[22] Pichard Brzezinskil The Army of Gustavus Adolphus, pp 11-13.

[23] Over the phone.

[24] It may also be significant that regiments of the main English field armies did not follow the practice of colour names, instead adopting and maintaining the tradition of calling themselves after their colonels - a practice which persisted into the regular armies of the 19th century (or even later if you count units such as Wingate's Chindits).

[25] Keith Roberts Soldiers of the English Civil War (1): Infantry, p 14.

[26] Keith Roberts Soldiers, p 15.

[28] Stuart Reid, 'Colours and Cornets', English Civil War Notes - Queries, 16, 11.

[29] Stuart Reid '1639 Snippets', English Civil War Notes - Queries, 9, 19.

[30] This quotation was passed on to me by Roger Emmerson.

[31] Indeed, if Samuel Luke is to be

believed several of the good merchants of London (Parliamentarian loyalists to a

man) were loath to let the small matter of warfare interfere with business. Luke's

scouts reported on several occasions that consignments of goods from London were

mysteriously finding their way to Oxford via a network of staging posts (The

Journal of Sir Samuel Luke, trans., and ed., by I.G. Philip).

Back to English Civil War Times No. 54 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com