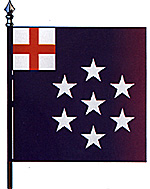

At right, Lord Brooke's or Grantham's Regt of Foot (Oxford, 27th Sept. 1642).

The ensigns carried by English infantry units during the

English Civil Wars are generally thought to have been

grouped into some kind of systematic order denoting

regiment and company. On this basis there have been

numerous attempts to 'reconstruct' regimental stands of

colours from isolated or incomplete sets of flags found in

contemporary sources. These efforts have yielded more or

less plausible results, although some designs continue to

resist reduction into a simple systematic order - most notably

those carried by Prince Rupert's Regiment of Foot and, to a

lesser extent, those carried by Sir Henry Bard's Regiment

[2].

But there is a problem. The 'reconstruction' of regimental

sets of flags is based on an assumption that the systematic

differentiation of companies within a regiment by their flags

was the norm. This assumption can, however, be questioned.

It is a view largely based on fairly scant evidence, most of it

derived from records of the colours carried by the London

Trained Bands and extrapolated to other units. There is,

however, no reason to suppose that all units in the civil wars

adopted such practices, and a good deal of circumstantial

evidence that many did not.

This article examines the extent to which regimental colours

in the civil war might, or might not, have conformed to some

system or other. In particular it considers whether two

particular designs of flag - stripes and gyrons - may have been

parts of a system or simpb isolated designs, using as evidence

examples drawn from the sixteenth century. These examples

suggest that there is no reason to suppose that all regiments

necessarily differentiated their companies in the same way

that the London Trained Bands did.

Additionally, there is no evidence at all that a system of striped flags was ever

employed, and that, while gyrons may have been systematically used in some regiments, there are no grounds for assuming either that there was a single gyronny system, or that all examples of gyronny flags were part of such a system.

It is important to clarify what I mean by 'a system' and

'systematic order' here. This is the question of how the

different companies of a regiment were distinguished one from

another by their flags, how those flags related to each other,

and what rules were implicit in the development of common

features in the flags.

A collection of flags, even of the same colour, bearing some similarity of design, and carried by several companies grouped into a regiment, do not constitute a system unless all the flags are related by some rule or other.

At right, King's Lifeguard of Foot (captured at Battle of Naseby, 14 June 1645). Source: Turmile Ms ff 144,145

In the circumstances these flags constitute more a set

than a system (see Figure 2) because knowing one flag in the

collection does not allow one to reconstruct any of the others

without seeing them first. Part of the interest of this set, it

however, is the partial system incorporating the rose motif.

Presumably these denote relatively junior officers,

whereas the others denote companies associated with

members of the royal family. Unfortunately there is no

independent evidence to corroborate this speculation, and, in

any case, even if true it still does not help much in the

identification of this set of flags as a system.

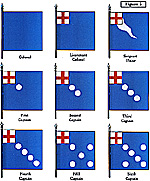

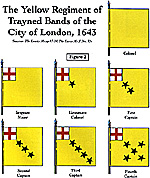

On the other hand, the well known sets of flags of the

London Trained Bands clearly do represent systems because

there are definite rules relating each flag in the set to the

others (see Figure 2). Knowing something about one of the

flags, its colour and devices, gives a reasonable basis on

which to reconstruct most, if not all, of the rest of the stand of

colours.

From what we know about English Civil War flags, th

re is good reason to believe that systems such as those

exemplified by the London Trained Bands colours were

widely adopted, at least in the Parliamentary armies. In

addition to contemporary, or near contemporary, illustrations,

such as those contained in the Levett and Lucas manuscripts

there are also surviving descriptions of flags. For example

there are several extant orders and receipts for flags (usually

in the name of Alexander Venner [4]

such as the following:

This passage strongly suggests a system like those

used in London, but it doesn't give enough detail to make the

identification certain. Unfortunately details of the

Colonel's, Lieutenant Colonel's or Major's colours are

missing - information that is crucial in deciding which, if any,

system the flags conformed to. The same is true of similar

documents that have also been found.

On the other hand, some sources are much more detailed. The well known letter from Charles Fairfax, written in 1649 to Adam Baynes ordering colours for his regiment, is a case in point:

This is a reasonably good approximation to what has

been called the Venn system, following a well known passage

from Captain Thomas Venn's Military Observations or the

Tacticke put into Practice (published in 1672 but referring to

pre 1660 practice) [6]

Venn was describing what he had seen rather than

offering a prescription, which is borne out not only by

Fairfax's letter, but also by other written and illustrative

sources (see Figure 3). Richard Elton, in his Compleat Body

of the Art Military (1650), illustrates the same system, as an

incidental detail to his description of regimental formation.

Perhaps this is not surprising because Major Elton was a

member of the White Auxiliaries of the City of London, and

also of the Westminster Military Company, and his illustration

shows the colours of the Trained Bands of the City of

Westminster [7] . But this

emphasis on London highlights a major problem.

It is obvious that the two main systems evidenced by

the London Trained Band colours - the Venn system (Figure

33) and what has been called the LTB system (Figure 2)

[8]

were used beyond the confines of London, but the extent of

their use is not really known for certain. More is known about

the flags carried by London Trained Band and Auxiliary units

than any other infantry units of the civil wars, with

the possible exception of the King's Lifeguard.

The Levett and Lucas manuscripts (as well as Symonds

copy of the former) show complete sets of (London)

colours, whereas other sources, such as Symonds

Diary and his Notebook (Harl. Ms 986) tend

not to - or are assumed not to. As a consequence, and

in order to fill presumed gaps left by the other sources, these

systems have been assumed to apply straightforwardly to

units beyond London, especially in the main English Field

armies. But there are grounds to doubt that this may always

have been the case.

There are around 100 (mainly unidentified) infantry

regiments about whose flags something is known.

[9]

Within this sample there are only 29 regiments whose flags

can reasonably be assumed to follow one or other of the

dominant London pattern systems: 7 clear examples of the

Venn system; 7 clear examples of the LTB system, with

perhaps another 7 possible; and 8 examples of a system using

piles as a differentiating device.

[10]

16 of these (about 55%) are London regiments, either

Trained Bands or Auxiliaries: 3 in the Venn system; 7 in the

LTB system; 6 in the piley system. Of the remainder, 2 of the

non-London examples of the Venn system depart from the

pure form of the system in having mottoes on the colonel's

colour; all 7 of the non-London examples of the LTB system

are problematic, having incomplete information or mixed

stands of colours; and 1 of the non-London examples of the

piley system is unclear and subject to contradictory

information in the contemporary sources

[11].

In other words only 3 non-London examples are known

which conform unambiguously to any of these systems

(around 3% of the entire sample of known regimental colours).

[12]

This is a very thin base on which to draw strong

inferences about practices outside London. [13] Even less is it a good basis

for assuming that the rules applying to the systems outlined

above also apply to other designs of flag, such as stripes or

gyrons.

Even the most partisan commentator would have to

admit that the London Militia - Trained Bands and Auxiliaries

- are a 'special case' in terms of English Civil War infantry. As

Ian Heath remarks, 'if an element of the militia was going to

achieve "elite" status it was inevitably going to be the

capital's own'. [14] Being

based in the nation's capital city, and therefore also close to

the centres of fashion, these units were in a position to be

aware of the latest developments in military theory and

practice from the continent. More important, they also had

the resources to keep up to date.

As Keith Roberts [15] notes, these units were well equipped, well trained,

and rather proud of their status. The same cannot be said

either of the trained bands from other localities, nor of the

field armies that were raised once the civil war got under way.

Although Keith Roberts [15] also emphasises that the London militia units and

military societies made military pursuits something of a

fashionable occupation, even outside the capital, it seems

nevertheless that the fashion took hold more strongly in

London than elsewhere.

Perhaps this should not be over emphasised, but it is

nevertheless an irnportant consideration when assessing the

plausible impact that London practice may have had on the

rest of the country. As in matters of sartorial fashion, the

details were likely to have travelled rather slowly into the

'provinces'. Certainly it gives grounds for being cautious

about extrapolating too far.

[1] It is important to emphasise that this article is only concerned with practices in English regiment during the civil wars Scotish practice was very different, and so, it seems, was Irish practice,

LTB system: The White Trained Bands, 1643; The Yellow Trained

Bands, 1643; The Blue Trained Bands, 1643; The Green Trained Bands, 1643; The

Orange Trained Bands, 1643; The Westminster Trained Bands, 1643; The Red

Auxiliaries, 1643; Dyve's Regiment, 1644; Lord Percy's Regiment, 1644; Talbot's

Regiment, 1644; Astley's and Stradling's Regiment (combined), 1644; Ashley's

(probably Sir Bernard Astley's) Regiment, 1644; Sir Ralph Hopton's Regiment,

1644; Cooke's Regiment, 1644.

Piley system: The Red Trained Bands, 1643; The Green Auxiliaries,

1643; The Mite Auxiliaries, 1643; The Yellow Auxiliaries, 1643; The Blue Auxiliaries,

1643; Thelwell's Regiment, 1644; The Westminster Auxiliaries (possibly), 1643; Sir

James Pennyman's Regiment, 1644. More Systems

Everybody "knows' that English infantry regiments during the civil wars differentiated their companies by systematically varying the numbers of a common device on their flags. Or did

they? This article suggests that even if they did, we don't really have very good evidence of it, and that the idea may have been over-extrapolated from a narrow base of evidence

relating to London. Instead the evidence points to rather more diversity of practice, especially with regard to flags whose designs are based on stripes or gyrons. [1].

Everybody "knows' that English infantry regiments during the civil wars differentiated their companies by systematically varying the numbers of a common device on their flags. Or did

they? This article suggests that even if they did, we don't really have very good evidence of it, and that the idea may have been over-extrapolated from a narrow base of evidence

relating to London. Instead the evidence points to rather more diversity of practice, especially with regard to flags whose designs are based on stripes or gyrons. [1].

Introduction

Designs, Sets and Systems

Thus, for example, the flags of the King's Lifeguard of Foot, although clearly related to one another, do not constitute a complete system because there is no obvious rule relating each flag, or the company it denotes, to all others in the collection [3].

Thus, for example, the flags of the King's Lifeguard of Foot, although clearly related to one another, do not constitute a complete system because there is no obvious rule relating each flag, or the company it denotes, to all others in the collection [3].

ECW King's Lifeguard of Foot Flags: Large (52K)

'paid Alexander Venner,for ten ensigns made each of

yellow taffetie witb distinctions of tawney in stara for Col. Holbourn

£ 40 (SP28/3/77) [5]

At right: The Trayned Bands of the Borough of Southwark, 1643. Source: The Levett Ms, pp63-72; The Lucas Ms f 35v.

At right: The Trayned Bands of the Borough of Southwark, 1643. Source: The Levett Ms, pp63-72; The Lucas Ms f 35v.

ECW Southwark Flags: Large (72K)

I am now to provide colours for my regiments. My dear Lord is pleaded I should have those I had before (being his own colours, blue and white), ... I would have the best taffaty of the deepest blue that can begotten for ten colours ... My own must have (within a well wrought round) these two words,(one under the other) Fideliter Faeliciter, ... The Lieutenant Colonel's is blue likewike, with the arms of England (viz. a cross gules) in the canton part. The maj . of

blue, with a red cross and white streaks. The eldest captain, and so every captain in his seniority, to be distinguished by white mullets in a blue field ... (Firth & Davies, 1940: 50

1).

As far as the dignity of an ensign in England (not

meddling with the Standard Royal) to a regimental dignity;

the colonel's colour, in the firit place, I'd of a clean pure

colour, without any mixture. The lieutenant colonel's only

with St. George's Armes in the upper corner next the staff; the

major's the same but with a little stream blazzant, and every

captain with St. George's Armes alone, but with so many

spots or several devices as pertain to the dignity of their

several places.

London's Disproportionate Impact

ECW Yellow Regt Trayned Bands of London 1643 Flags: Large (97K)

The London Trained Bands

Notes

[2]. See, for details, Stuart Peachey & Les Prince (1991), ECW Flags - Colours I - The English Foot, pp 85-86; 100; 102 - 103; Steve Ede-Borren, "The Colours of Prince Ruperts Blew Regiment of Foot", English Civil War Notes & Queries, 14, 5-7; John Matthewa, "The colours of Prince Rupert's Regiment of Foot: A reconstruction," English

Civil War Notes & Queries, 17, 6.

[3] 3. These flags, having an obvious basis

in Royal Heraldry, may well be related by rules of precedence drawn from heraldic

practice. Unfortunately no such rule has yet been plausibly identified, and therefore for

current purposes it is safest to presume there is none.

[4] Venner crops up regularly in relation

to flags ordered for Parliamentarian units. Unfortunately he is frustratingly elusive in

other respects; if it were possible to track him down it may be possible to discover

details of other Parliamentarian colours, specifically those carried by New Model

Army units of which little is known.

[5] Quoted in Peachey & Prince op. cit., p

32. See also Peachey & Torten (1987) Old Robin's Foot, pp 40 41.

[6] See Peachey & Prince,

op. cit., p 12 - 13. I say that is a reasonable approximation

because the addition of the motto is a departure from the system as described by

Venn, and Fairfax's use of the word 'streaks' (in the plural) to describe the major's

colour leaves some room to ask whether he really was referring to the single wavy

pile (stream blazant) of the Venn system. These are, of course, nit picking points,

but, as the saying goes, 'the Devil is in the detail', and it is from such small elements

that new information is often found. The term 'stream blazant', from Venn's description, is

not, incidentally, an heraldic description, and it is something of an article of

faith that he was describing the wavy pile familiar from the London Trained Band

examples.

[7] Ibid. See also Keith

Roberts (1987) London & Liberty: Ensigns of the London Trained Bands,

[8] Peachey & Prince, op cit.

There is also a subsidiary system evident in these flags

based on wavy piles, exemplified by the Red Trained Bands, and the White, Yellow,

Blue, Green and Westminster Auxiliaries - see Peachey & Prince, pp 49 - 53. See

also Roberts op cit.

[9] Peachey & Prince op cit.

This is a rough estimate. There are around 48 sets or partial sets of flags known, and

around 52 isolated flags. However, this figure does not include identified regiments

whose field colour is known but without any details of devices. Furthermore,

isolated flags may well have been

carried by the same units, but without further information no firm conclusions can be

drawn about this.

[10] The system of

differentiation using piles, either straight or wavy, is really an

intermediary system which sits between the Venn system and the LTB system. It

could reasonably be classified as an example of the latter, but for most practical purposes

it is more useful to treat it separately.

[11] Peachey & Prince op

cit., pp 12 -15. The Final regiment referred to is Sir James

Pennyman's regiment. Richard Symonds in his Notebook (Harl. Ms 986) records an

ambiguous drawing of the flags for this regiment, suggesting a green field with red

piles wavy (thus violating heraldic rules of tincture). But he also includes an

enigmatic note suggesting that the regiment had ten flags with green fields and white

stars. From this it is not at all clear what the regiment carried.

[12] The complete list is:

Venn system: The Southwark Trained Bands, 1643; The Orange Auxiliaries, 1643; The City of Oxford Regiment, 1644; Charles Fairfax's Regiment,

1650; an unidentified Parliamentarian regiment from St. Newbury, 1643.

[13] In relation

to this point, it is perhaps worth noting, as Dave Ryan pointed out to me on the phone

recently, that the Earl of Essex's Army and later the New Model Army were both based

in London although strictly speaking 'national' armies. Furthermore, Levett, who

prepared the manuscript containing the best representations of the London Trained

Band colours, is known to have been a Royalist spy. His manuscript was also

painstakingly copied by that great seventeenth century heraldic anorak, Richard

Symonds, so presumably London practice was known even in Oxford.

[14] Ian Heath Armies of the Sixteenth Century, p 36.

[15] Keith Roberts London & Liberty.

Back to English Civil War Times No. 54 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com