Conclusion

With the departure of the Danish fleet in 1070 and the suppression of the Fenland rebellion William could finally relax somewhat from his constant campaigning that he had carried out since his coronation of 25 December 1066. While there would still be numerous threats --both foreign and domestic-- against his New Kingdom, it would never be as bleak as the initial five years following his accession to the English throne.

Although William’s personal stamina, the mounted Norman knights, and their armor and weapons were highly beneficial to his victories, it was the castle in the end that allowed King William to consolidate his newly-won territories and hold them against determined opposition to his rule. No historian can define more succinctly the value of William’s use of castles in his strategic development than Douglas in his Epic “William the Conqueror” which states:

- To the absences of castles, indeed, Ordericus Vitalis, who is here following William of

Poitiers, attributes the lack of success of the opponents of King William in England during

this warfare. Such was the English situation. By contrast, William in his English campaigns

evidently employed precisely the same device [Castles] which he had earlier used in France,

and the Bayeux Tapestry shows no substantial difference between the castles at Dol, Rennes,

or Dinant, and that which was erected at Hastings in 1066.

Appendix

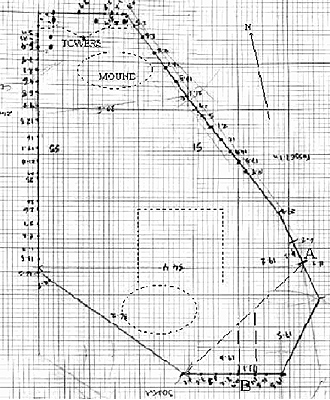

Map of the lower Norman fort at Hastings. The illustration indicates the location of post holes and the design of the fort.

Map of the lower Norman fort at Hastings. The illustration indicates the location of post holes and the design of the fort.

Early castles of the Motte-and-Bailey construction were wood and earthen fortification. Burke gives an outstanding description of one of these castles in his work entitled Life in the Castle in Medieval England:

- The first of these hurriedly erected forts followed a simple basic plan, still to be

detected under or within the outlines of even the most complex later strongholds of England

and Wales. This was the motte-and-bailey method of construction. The motte was a steep

cone of hard-packed earth, flattened at the top. The trench left around its base by the removal

of earth for the mound became itself part of the defense as a dry of wet moat, to which the word

‘motte’ was later corrupted and transferred. The level of the mound was encircled by a

stockade of sharpened stakes, and some form of tower would be raised inside, originally of

wood but in due course of stone.

A wooden bridge over the ditch joined the motte to its bailey, an enclosure within a double defense of banked-up earthwork and a further loop of ditch. This loop usually connected the motte ditch to make a figure of eight. Within the bailey were stables, barns, stores and bakehouse, armourers’ and farriers’ workshops, ad living quarters for the lord and his retainers. Access from the outer world was by means of a drawbridge, hauled up at the first sign of approaching danger. If enemies nevertheless succeeded in penetrating the bailey, the defenders fled to their last refuge on the motte, demolishing the inner bridge and wooden steps behind them.

References

Brown, R. Allen. Castles, Conquest and Charters, Collected Papers. Woodbridge, The Boydell Press, 1989. An Historian’s

approach to the origins of the Castle in England and the argument that English Castles are the invention of the Norman invaders.

Brown, R. Allen. The Norman Conquest of England. Woodbridge, The Boydell Press, 1995. Sources and Documents

from Anglo-Saxon and Norman England during pre- and post Norman conquest.

Burke, John. The Castle in Medieval England, Totowa, Rowman and Littlefield, 1978. The evolution of the English Castle.

Douglas, David C. The Norman Achievement, 1050-1100. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1969. The study of the spreading Norman culture and society by their use of military force in England, Italy and Sicily.

Douglas, David C., William the Conqueror, The Norman Impact upon England. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1964. The study of how William impacted upon Anglo-Saxon England after his conquest of the country in 1066.

Gravett, Christopher., Hastings 1066, The Fall of Saxon England. London, Osprey Publishing, 1998. An evaluation of the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the defeat of Saxon England by the forces of William of Normandy.

Gravett, Christopher., Norman Knights, 950-1204 AD. London, Osprey Publishing, 1997. A concise evaluation of Norman Knights covering their equipment, tactics, and campaigns.

Harrison, Mark., Anglo-Saxon Thegn, 449-1066 AD. London, Osprey Publishing, 1998. A concise study of the Anglo-Saxon Thegn evaluating his equipment, tactics, and campaigns.

Hollister, C. Warren., Anglo-Saxon Military Institutions, On the eve of the Norman Conquest. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1962. The study of the military organization of the Anglo-Saxon forces leading up to the Norman Conquest of England.

Hollister, C. Warren., Military Organization of Norman England. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1965. The exhaustive study of Norman military organization prior to and after the conquest of England by William the Conqueror.

Humble, Richard. The Fall of Saxon England. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1975. A study in the causation of the fall of Saxon England.

Nicolle, David. The Normans. London, Osprey Publishing, 1996. The concise study of the Norman military forces to include their equipment, tactics, and campaigns.

Pounds, N.J.G. The Medieval Castle in England and Wales. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990. A political and social history of castles of England.

Renn, D. F., Norman Castles in Britain, Chatham, Kent, W & J Mackay & Co LTD, 1968. A study of Norman castles and their evolution in Britain.

Tetlow, Edwin. The Enigma of Hastings. New York, St. Martin’s Press, Inc., 1974. An evaluation of the misunderstandings about the Battle of Hastings and the historical truths.

Whitelock, Dorothy, et al. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Trans, Westport, Greenwood Press, Publishers, 1961. The documents of the Anglo-Saxons, prior to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 giving a detail look at their culture and society.

Wise, Terence. Saxon, Vikings, and Norman. London, Osprey Publishing, 1997. The concise study of the three forces which impacted upon England from 449-1200 AD.

More Role of Castles in William the Conqueror's Victory

-

Introduction

Opposing Forces: Anglo-Saxon and Norman

Battle Of Hastings

Fortifications and Castles in England

Post Hastings Conquest

1067-70, William’s Kingdom in Peril

Conclusion, Appendix, and References

Back to Cry Havoc #34 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com