Pontiac's War: In the Great Lakes country the Ottawa Chief Pontiac had secretly assembled a confederation of Indian tribes to unleash a war upon the English and drive them from their far-flung outposts in the Northwest. Pontiac's War began in May 1763 with the British posts at Michilimackinac, Presque Isle (Erie), Le Boeuf (Waterford) and Venango falling to the Indians; only Detroit, Niagara, Pitt and Ligonier would survive Pontiac's uprising. Indian war parties ranged far and wide across the Pennsylvania frontier. Fleeing settlers sought safety in the forts and blockhouses that studded the wilderness, and the towns of Carlisle and Shippensburg filled with hundreds of destitute and starving refugees bearing tales of the horrors of Indian depredations.

To start with one needs to look at the American Indian, whose anarchistic political life, and communistic economic life was far different than that of the European settlers. The basic nature of the Indian lifestyle prevented any

attempt at a major political organization from succeeding, as no one Indian could ever force another to do something that the second Indian did not want to do. They could persuade, they could attempt to lead, they could offer bribes and rewards, but they could not force a warrior into a battle that he did not wish to go. Their economic structure meant that all shared equally in good times and bad, but did not allow them to build up the resources needed to fight any sort of sustained warfare.

Contrast this to the settlers on the American shore at the same time. Once a decision had been arrived at, all were to obey it, with punishments laid out for those who refused. A warrior who refused battle could be punished with death, while the economic structure stressed the need to build up resources at the expense of others. This ability to do that allowed for troops to be maintained in the field for years if necessary, and allowed for warfare to be carried out on a level unknown to the American Indian before 1500.

During the first half of the so-called "Second Hundred Years War of 1688 to 1815", fought between France and England, the American Indian found himself as a willing piece on the game board of this struggle. The woodland Indians found themselves needed by both sides, and able to demand gifts and presents as preconditions for their help. Confederations such as the Iroquois which were led by able leaders ensured that their voice was heard by the governments of both the French and British Colonies. Attempts by both sides to keep or switch the alliances of the Indian tribes were a consistent staple of political life for the tribes, and threats made by them that they might change sides were heeded.

These wars had an effect upon the Indian tribes unforeseen by the Indian leadership. Trade goods such as muskets, powder, shot, metal knives, hatchets, and trinkets had all become a part of the Indian lifestyle, and had replaced handmade items used before. Prior to the French and Indian war of 1754-1760, these had been obtained through trade, or as gifts from the governments attempting to make peace with the different Indian tribes. The musket, with its need for powder and shot, replaced the bow as the main war weapon, and any tribe without it was easy prey for those with it.

The last French and Indian War of 1754-1761 changed the way that warfare in America was fought, and undermined the bargaining position of the American Indians. The fact that for the first time both England and France were willing to raise and/or send large numbers of troops into the field meant that the Indians' usefulness had come to an end. The French, forced to campaign with a limited number of soldiers, had to continue to deal with the temperamental nature of the Indian warrior in an attempt to balance the odds against them. The British in contrast, unwilling to put up with the ways of the Indians, raised special units of Rangers and Light Infantry.

Before 1754, the ability to include Indians in yourforce could make the difference between victory or defeat, but after 1754 the need forthem steadily declined. True, the Indians were very useful for the "petit war" of outposts and raids, and their presence on a battlefield could be a major morale factor against any force arrayed against them, but as the 1750s wore on they became less and less of a military factor for the armies in North America. The fall of New France when Montreal surrendered on September 8, 1760, confirmed in the mind of the British Commander in Chief, General Jeffery Amherst, that Indians were not needed as they had been in the past.

After the fall of Monteal, and the end of French resistance in New France, British units spread out across the area of the Northwest to garrison the newly surrendered French posts. Detroit was garrisoned by the end of 1760, but most of the other posts were not reached till 1761. Several problems quickly arose to trouble the newly arrived British garrisons as they moved into position.

Problems

First of all, British troop strength in North America was cut as troops were moved south to the Caribbean to help capture the French colonies there, as well as to engage England's newest enemy, Spain. The British government saw no reason to maintain unneeded troops in Americawhen the riches of the Spanish Main and the Sugar Isles beckoned. The fact that troops sent there tended to be decimated by fever was not considered as important, but it guaranteed that troops sent there could not be shuttled back quickly as reinforcements, as the troops tended to be fever ridden and unfit for active service.

Second of all, with the exception of the former French posts at Fort Niagara and Detroit, most of the newly captured French posts were little more than stockaded trading posts. Those posts which had been destroyed by the French at Venango, Presque Isle, and at the forks of the Ohio (Fort Duquesne then Fort Pitt), were rebuilt, but the problems of garrisons still remained. Most posts were left with less than 20 men as garrisons, while larger forces concentrated at Detroit, Niagara, and Fort Pitt. The French garrisons had been based on the idea of showing the flag more than anything else, and they made no attempt to hold the territory about them. They existed as forts by the grace of the local Indians, and the Indians knew it. The new British garrisons moved into these posts as conquerors, and did not pay the Indians the respect that the local tribes felt was due them.

Third, the removal of the French threat meant that most of the American colonies disbanded their provincial forces, further cutting down on the available troop strength. With the numbers of British troops that had been moved through the colonies during the war, the colonies were even less inclined to respond to requests for troops and aid from the British military. Experienced officers, both regular and provincial, left the service as they thought that North America was now a backwaterwhere noth i ngwould be happening, and returned home.

Against the wishes of his two advisors on Indian Affairs, General Amherst made another error. Sir William Johnson, and George Croghan were experienced Indian traders who had been accepted by the tribes with which they worked. Sir William Johnson had been adopted into the Iroquois as a chief and better understood the Indian mind than anyone else on the continent. George Croghan had years of experience in dealing with tht tribes of western Pennsylvania and those of the Northwest. Amherst, in an effort to cut costs, slashed the budget of the Indian Department as he no longer felt it necessary to "buy" the support of the Indians. Both Johnson and Croghan attempted to down play the impact of Amherst's decision throughout 1861-62 by often giving out gifts out of their own personal funds, but by 1762 the Indians realized what Amherst's decision was, and what impact it would have on them.

Amherst had decided that the easiest way to bring the tribes under control was to restrict their supplies of powder and shot, and thus deprive the Indian tribes from the start of any ability to resist. The Cherokee had been brought under control in this manner, and Amherst felt that this was the simple solution to the problem. The fact that both Croghan and Johnson were appalled at this decision and protested he ignored, as he felt that they were too soft on the Indians, and too involved in making a profit out of the Indian trade.

Cutoff from any aid from their French "Father" and unable to occupy their old spot as the balance of power, the American Indians would have been forced to submit to these actions had fate not dealt them two cards to play. The first, and most important was that while New France had indeed surrendered on September 8th, 1760, the war was not yet over. French Louisiana still remained as a French colony, and proof that France was not yet driven off the continent. To the French citizens of the Northwest, hope remained that they would not be ceded to British control by the terms of a peace treaty. After all, in 1748 Louisburg had been returned to French even though it had been captured by New England troops in 1745. If the British could be driven from the area before the peace treaty was signed, the inhabitants could hope to remain under the French Flag. Throughout this period, trappers and traders, as well as other messengers moved back and forth from the Illinois Country, where the French still ruled, to the Lakes area bringing words of encourangement for an Indian uprising that would bring back the French Flag.

The second card was the relative weakness of the British Army in the area of the Northwest. The British forces in the area were not strong enough to convincethe Indians not to fight. They tended to serve primarily as reminders to the Indians of the fact that times had changed, and their attempts to enforce the trade laws 'of Amherst only tended to ensure that the Indians would not forget their presence. The one British Fort to escape attack was Fort Edward Augustus where the fort's commander, one Lieutenant James Gorrell, realized the position that he was in and made no effort to enforce the rules on Indian trade. In the end the British Army's attempt to hold this area with small detachments only resulted in their establishing a number of "penny packets" that the Indians could attack and destroy in detail.

In 1851 the great historian Francis Parkman published his "THE HISTORY OF THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC", which made the local chief of the Ottawa at Fort Detroit, Pondiac, into "Pontiac", the great organizer and leader of the Indian rebellion of 1763. Pondiac was a war chief of his tribe, but not the chieftain of the revolt that Parkman makes him out to be.

To Parkman, it seemed inconceivable that the Indians would act as they did without a leader to organize and guide them along -- yet a serious look at this conflict shows that there was no overall leadership. Rather in the spring of 1763, the frustration and anger which had been building up since 1760 in the Indian camps came to the boiling point, and the result was the socalled "Pontiac's War". Pontiac got the credit for the war in the European mind as the critical sector was that at Fort Detroit, where Pontiac was the Indian commander (insofar as the nature of the Indians could have a commander). However, at no time did Pontiac have the influence that he was credited with, for had he been that powerful the revolt would have been far more successful.

As it was the Indians did not do all that badly. Forts Sandusky, St. Joseph, Miami, Ouiatanon, Michlimackinac, Presque Isle, Venango, and LeBoeuf, were all captured between May 16th and June 18th. By the end of June the British were left holding only Fort Pitt, Fort Ligonier, Fort Niagara, and Fort Detroit, with the frontier open to Indian attacks from New York south to Virginia. Amherst's hope thatthe Indians would run out of supplies quickly failed to materialize as the Indians captured the holdings of the fur traders in the area, British Army convoys, and the Forts themselves. As the summer passed, the Indians found themselves better equipped and supplied than they had been for years.

At the start of the outbreak, most tribes tended to hold back, awaiting the outcome of events. As post after post fell, the attacking Indians grew richer; they also grew stronger as more and more braves joined in. Word that a given post had fallen encouraged the tribes about the next post to attack, and join in the spoils. Co-operation was by no means the rule. After Fort Michlimackinac fell to a Ch ippewa attack, the Ottawa -- their local rivals -- took charge of the prisoners and along with a delegation from the Menominee tribe brought the survivors, as well as the garrison from Fort William Augustus (Green Bay) safely to Montreal.

Amherst's attempt to send reinforcements to the frontier met with mixed success. Colonel Henry Bouquet of the 60th Foot, the Royal Americans, was sent with a relief column to Fort Pitt. The British strength had fallen to the point that Bouquet could only find 113 men of his regiment, 214 soldiers from the 42nd (the Black Watch), and 133 men of the 77th Regiment, another Highland unit. The last named force had 60 men so ill that they had to be transported in wagons at the start of the march, for to leave them behind would cost Bouquet an eighth of his command. Bouquet's column fought its way through an Indian ambush at Bushy Run and managed to relieve Fort Pitt, but at a heavy price -- a loss of 115 men killed or wounded in this one action.

Captain Dalyell, who was Amherst's aide de camp, was given the task of reinforcing both Fort Niagara and Detroit. After reinforcing Fort Niagara he pressed on to Fort Detroit, where he reflected Amherst's belief that the Indians were not a power to be reckoned with. Against the advice of the Fort's Commander, Major Gladwin, who had held Detroit when all other British posts had fallen, Dalyell attempted to sortie and scatter Pontiac's besieging forces. The attack failed, costing Dalyell his life and negating the effect that the arrival of the reinforcements had on the Indians there. In a turn about, the British supply line at Niagara came under attack in September, and needed reinforcements did not move up to Detroit that year as they were held back to protect that fort.

The key to the survival of Detroit turned out to be the ships of the British Quartermaster Department. These ships, the MICHIGAN, and the HURON, were armed with light cannon and swivels, and provided the lifeline to Detroit throughout the siege. They brought in reinforcements and supplies, took out wounded and calls for help, and were attacked by not only Indians in canoes, but by fire rafts as well. The MICHIGAN was wrecked in August of 1763, but not before she had performed sterling service running back and forth between Niagara and Detroit.

The realization of the seriousness of this outbreak was to have afar reaching effect on American History. Additional troops were sent to America from England for duty as a garrison, and provincial forces raised again. The newly crowned King of England, George III, proclaimed a line of settlement that no one must cross until affairs were straightened out with the Indians. Troops under Colonels Bradstreet and Bouquet took to the field in 1764 - whereas Bouquet had 500 soldiers under command for the 1763 campaign, in 1764 he had some 1500 men.

The arrival of these forces in the summer/fall of 1764 crushed the revolt, though Bradstreet's attempts to negotiate with the Indians at Detroit in 1764 gave back to the Indians almost all that they had lost on the battlefield. In the end, Bouquet's expedition into the heart of the Indian country in what is now Ohio brought an end to the war, and a peace treaty that lasted until 1774.

The long term effect of this war was to indirectly bring about the American War of Independence. Troops needed to keep the Indians in check had to be paid, and the colonies for the first time were asked to do so. The "Proclamation Line of 1763" was to be adjusted as time passed and new treaties were signed with the Indian tribes opening up new lands for settlements; yet settlers were always moving ahead of the line. The Indian Revolt of 1763 ended up speeding, not stopping, the westward tide of settlement.

Pontiac's Rebellion A Different Type of War

When one studies Pontiac's Rebellion, one has a difficult time deciding just where one should place it in the field of American History. Is it part of the continuing drama of the Native American as he attempted to stop the onrush of the European settlers across his homeland? Is it an Epilogue to the Seven Years War in America - the last of the famed French and Indian Wars? Or should one consider it as the Prologue to the American War of Independence, which was to breakouta mere 12 years hence? It is perhaps a mixture of all of these, and for these reasons the historical miniatures gamer will find it a very different and interesting period.

When one studies Pontiac's Rebellion, one has a difficult time deciding just where one should place it in the field of American History. Is it part of the continuing drama of the Native American as he attempted to stop the onrush of the European settlers across his homeland? Is it an Epilogue to the Seven Years War in America - the last of the famed French and Indian Wars? Or should one consider it as the Prologue to the American War of Independence, which was to breakouta mere 12 years hence? It is perhaps a mixture of all of these, and for these reasons the historical miniatures gamer will find it a very different and interesting period.

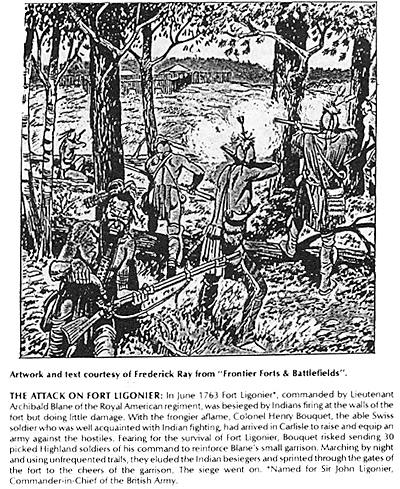

THE ATTACK ON FORT LIGONIER: In June 1763 Fort Ligonier', commanded by Lieutenant Archibald Blane of the Royal American regiment, was besieged by Indians firing at the walls of the fort but doing little damage. With the frongier aflame, Colonel Henry Bouquet, the able Swiss soldierwho was well acquainted with Indian fighting, had arrived in Carlisle to raise and equip an army against the hostiles. Fearing for the survival of Fort Ligonier, Bouquet risked sending 30 picked Highland soldiers of his command to reinforce Blane's small garrison. Marching by night and using unfrequented trails, they eluded the Indian besiegers and sprinted through the gates of the fort to the cheers of the garrison. The siege went on. 'Named for Sir John Ligonier, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. Artwork and text courtesy of Frederick Ray from "Frontier Forts & Battlefields".

THE ATTACK ON FORT LIGONIER: In June 1763 Fort Ligonier', commanded by Lieutenant Archibald Blane of the Royal American regiment, was besieged by Indians firing at the walls of the fort but doing little damage. With the frongier aflame, Colonel Henry Bouquet, the able Swiss soldierwho was well acquainted with Indian fighting, had arrived in Carlisle to raise and equip an army against the hostiles. Fearing for the survival of Fort Ligonier, Bouquet risked sending 30 picked Highland soldiers of his command to reinforce Blane's small garrison. Marching by night and using unfrequented trails, they eluded the Indian besiegers and sprinted through the gates of the fort to the cheers of the garrison. The siege went on. 'Named for Sir John Ligonier, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. Artwork and text courtesy of Frederick Ray from "Frontier Forts & Battlefields".

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com